Ucla Archaeology Field School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zapotec Empire an Empire Covering 20 000 Sq

1 Zapotec Empire an empire covering 20 000 sq. km. This empire is thought to have included the Cen- ARTHUR A. JOYCE tral Valleys (i.e., the Valleys of Oaxaca, Ejutla, University of Colorado, USA and Miahuatlán) and surrounding areas such as the Cañada de Cuicatlán as well as regions to the east and south extending to the Pacific Archaeological and ethnohistoric evidence coastal lowlands, particularly the lower Río from Oaxaca, Mexico, suggests that Zapo- Verde Valley. These researchers argue that tec-speaking peoples may have formed small Monte Albán’s rulers pursued a strategy of empires during the pre-Hispanic era (Joyce territorial conquest and imperial control 2010). A possible empire was centered on through the use of a large, well-trained, and the Late Formative period (300 BCE–200 CE) hierarchical military that pursued extended city of Monte Albán in the Oaxaca Valley. campaigns and established hilltop outposts, The existence of this empire, however, has garrisons, and fortifications (Redmond and been the focus of a major debate. Stronger Spencer 2006: 383). Evidence that Monte support is available for a coastal Zapotec Albán conquered and directly administered Empire centered on the Late Postclassic outlying regions, however, is largely limited – (1200 1522 CE) city of Tehuantepec. to iconographic interpretations of a series of Debate concerning Late Formative Zapotec carved stones at Monte Albán known as the imperialism is focused on Monte Albán and “Conquest Slabs” and debatable similarities its interactions with surrounding regions. in ceramic styles among these regions (e.g., Monte Albán was founded in c.500 BCE on Marcus and Flannery 1996). -

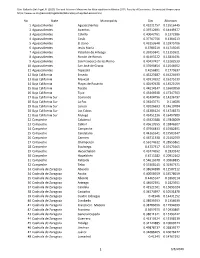

No. State Municipality Gini Atkinson 1 Aguascalientes Aguascalientes

Cite: Gallardo Del Angel, R. (2020) Gini and Atkinson Measures for Municipalities in Mexico 2015. Faculty of Economics. Universidad Veracruzana. https://www.uv.mx/personal/rogallardo/laboratory-of-applied-economics/ No. State Municipality Gini Atkinson 1Aguascalientes Aguascalientes 0.43221757 0.15516445 2Aguascalientes Asientos 0.39712691 0.14449377 3Aguascalientes Calvillo 0.40042761 0.1372586 4Aguascalientes Cosío 0.37767756 0.1304213 5Aguascalientes El Llano 0.43253648 0.15975706 6Aguascalientes Jesús María 0.3780219 0.11715045 7Aguascalientes Pabellón de Arteaga 0.39355841 0.13155921 8Aguascalientes Rincón de Romos 0.41403222 0.15831631 9Aguascalientes San Francisco de los Romo 0.40437427 0.15282539 10Aguascalientes San José de Gracia 0.37699854 0.12548952 11Aguascalientes Tepezalá 0.4256891 0.1779637 12Baja California Enseda 0.43223187 0.16224693 13Baja California Mexicali 0.43914592 0.16275139 14Baja California Playas de Rosarito 0.42097628 0.14521059 15Baja California Tecate 0.44214147 0.16600958 16Baja California Tijua 0.45446938 0.17347503 17Baja California Sur Comondú 0.41404796 0.14236797 18Baja California Sur La Paz 0.36343771 0.114026 19Baja California Sur Loreto 0.42026693 0.14610784 20Baja California Sur Los Cabos 0.41386124 0.14718573 21Baja California Sur Mulegé 0.42451236 0.16497989 22Campeche Calakmul 0.45923388 0.17848009 23Campeche Calkiní 0.43610555 0.15846507 24Campeche Campeche 0.47966433 0.19382891 25Campeche Candelaria 0.44265541 0.17503347 26Campeche Carmen 0.46711338 0.21462959 27Campeche Champotón 0.56174612 -

Movilidad Y Desarrollo Regional En Oaxaca

ISSN 0188-7297 Certificado en ISO 9001:2000‡ “IMT, 20 años generando conocimientos y tecnologías para el desarrollo del transporte en México” MOVILIDAD Y DESARROLLO REGIONAL EN OAXACA VOL1: REGIONALIZACIÓN Y ENCUESTA DE ORIGÉN Y DESTINO Salvador Hernández García Martha Lelis Zaragoza Manuel Alonso Gutiérrez Víctor Manuel Islas Rivera Guillermo Torres Vargas Publicación Técnica No 305 Sanfandila, Qro 2006 SECRETARIA DE COMUNICACIONES Y TRANSPORTES INSTITUTO MEXICANO DEL TRANSPORTE Movilidad y desarrollo regional en oaxaca. Vol 1: Regionalización y encuesta de origén y destino Publicación Técnica No 305 Sanfandila, Qro 2006 Esta investigación fue realizada en el Instituto Mexicano del Transporte por Salvador Hernández García, Víctor M. Islas Rivera y Guillermo Torres Vargas de la Coordinación de Economía de los Transportes y Desarrollo Regional, así como por Martha Lelis Zaragoza de la Coordinación de Ingeniería Estructural, Formación Posprofesional y Telemática. El trabajo de campo y su correspondiente informe fue conducido por el Ing. Manuel Alonso Gutiérrez del CIIDIR-IPN de Oaxaca. Índice Resumen III Abstract V Resumen ejecutivo VII 1 Introducción 1 2 Situación actual de Oaxaca 5 2.1 Situación socioeconómica 5 2.1.1 Localización geográfica 5 2.1.2 Organización política 6 2.1.3 Evolución económica y nivel de desarrollo 7 2.1.4 Distribución demográfica y pobreza en Oaxaca 15 2.2 Situación del transporte en Oaxaca 17 2.2.1 Infraestructura carretera 17 2.2.2 Ferrocarriles 21 2.2.3 Puertos 22 2.2.4 Aeropuertos 22 3 Regionalización del estado -

A Grammar of Umbeyajts As Spoken by the Ikojts People of San Dionisio Del Mar, Oaxaca, Mexico

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following reference: Salminen, Mikko Benjamin (2016) A grammar of Umbeyajts as spoken by the Ikojts people of San Dionisio del Mar, Oaxaca, Mexico. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/50066/ The author has certified to JCU that they have made a reasonable effort to gain permission and acknowledge the owner of any third party copyright material included in this document. If you believe that this is not the case, please contact [email protected] and quote http://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/50066/ A Grammar of Umbeyajts as spoken by the Ikojts people of San Dionisio del Mar, Oaxaca, Mexico Mikko Benjamin Salminen, MA A thesis submitted to James Cook University, Cairns In fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Language and Culture Research Centre, Cairns Institute College of Arts, Society and Education - James Cook University October 2016 Copyright Care has been taken to avoid the infringement of anyone’s copyrights and to ensure the appropriate attributions of all reproduced materials in this work. Any copyright owner who believes their rights might have been infringed upon are kindly requested to contact the author by e-mail at [email protected]. The research presented and reported in this thesis was conducted in accordance with the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research, 2007. The proposed research study received human ethics approval from the JCU Human Research Ethics Committee Approval Number H4268. -

The Economy of Oaxaca Decomposed

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern University Honors Program Theses 2015 The conomE y of Oaxaca Decomposed Albert Codina Sala Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the Growth and Development Commons, Income Distribution Commons, International Economics Commons, Macroeconomics Commons, and the Regional Economics Commons Recommended Citation Codina Sala, Albert, "The cE onomy of Oaxaca Decomposed" (2015). University Honors Program Theses. 89. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/89 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Economy of Oaxaca Decomposed An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in Department of Finance and Economics. By Albert Codina Sala Under the mentorship of Dr. Gregory Brock ABSTRACT We analyze the internal economy of Oaxaca State in southern Mexico across regions, districts and municipalities from 1999 to 2009. Using the concept of economic convergence, we find mixed evidence for poorer areas catching up with richer areas during a single decade of economic growth. Indeed, some poorer regions thanks to negative growth have actually diverged away from wealthier areas. Keywords: Oaxaca, Mexico, Beta Convergence, Sigma Convergence Thesis Mentor: _____________________ Dr. Gregory Brock Honors Director: _____________________ Dr. Steven Engel April 2015 College of Business Administration University Honors Program Georgia Southern University Acknowledgements The first person I would like to thank is my research mentor Dr. -

Fuzzy Modeling of Migration from the State of Oaxaca, Mexico

Fuzzy Modeling of Migration from the State of Oaxaca, Mexico Anais Vermonden and Carlos Gay Programa de Investigación en Cambio Climático, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, CU, Mexico Keywords: Fuzzy Logic, Migration, Oaxaca, Mexico, ANFIS. Abstract: This study shows an important innovation with the use of fuzzy logic to develop models on the migration factors occurring in the state of Oaxaca, México, since fuzzy logic has not been applied in this field. Migration is a complex system as individuals make their own decision to migrate. The major factors causing migration are: higher employment in the primary sector, high grades of unemployment, high marginalization index, small communities, soil degradation, violence and remittance received. Another tendency shown in these models is that municipalities in Oaxaca with greater levels of education are having higher migration levels due to the lack of opportunities to continue studies or well-paid jobs. Climate change may impose greater movement of people as it can worsen the already precarious soil situation. Even if the models present some error in the calculation of the migration index, it made clear what other variables should be included to show the impacts of climate change on migration. 1 INTRODUCTION 2013). There are a number of causes for the migration Oaxaca is located in southwest Mexico; it is divided from Oaxaca, and some of the most significant are into 570 municipalities. Oaxaca is one of the poorest lack of economic development, need for states with 61.9% of the population living under the diversification of income (remittance), ecological poverty line and, has one of the highest rates of rural deterioration, lack of educational opportunities, migration. -

Ethnohistorical Archaeology in Mexico 2015 Field School

ANNUAL REPORT: ETHNOHISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY IN MEXICO 2015 FIELD SCHOOL Director(s): John M. D. Pohl, UCLA and CSULA Co-Director(s): Danny Zborover, Brown University The 2015 team exploring a deep cave at the archaeological site of Guiengola The 2015 season of the Ethnohistorical Archaeology in Mexico field program was our most ambitious yet, at least in terms of geographical coverage. We started from exploring archaeological and historical sites in Mexico City and its surrounding, followed by a few days in the shadow of the Great Pyramid of Cholula. We then took a long drive up and down from Cacaxtla to the Pacific Coast, to the once powerful Mixtec kingdom of Tututepec. The rest of our time on the coast was spent in Huatulco, one of the most important trade ports in the Late Postclassic and Early Colonial period and a vibrant hub to Pochutec, Zapotec, Mixtec, Chontal, and other ethnic groups. From there we continued to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, the Zapotec kingdom antagonistic to the Mixtecs, and explored the ruined fortress-temples of Guiengola. The third week was dedicated to the amazing sites, museums, and living cultures of the Valley of Oaxaca, and we even got a glimpse of the Guelaguetza festivity preparations. The last week went by fast in between site-seeing and codex-deciphering in the Mixteca Highlands, which we explored from our home bases at the Yanhuitlan convent and the Apoala scared valley. While seemingly distant from each other in space and time, these sites and regions are all connected and played an important role in one long and interwoven story. -

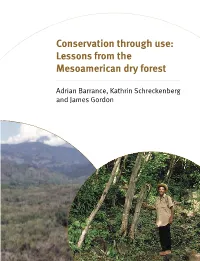

Lessons from the Mesoamerican Dry Forest Dry Mesoamerican the from Lessons Use: Through Conservation

Conservation through use: Lessons from the Mesoamerican dry forest This book examines the concept of ‘conservation through use’, using the conservation of tree species diversity in Mesoamerican tropical dry forest in Honduras and Mexico as a case study. It discusses the need to develop conservation strategies based both on a botanical determination of those species most in need of conservation and an Conservation through use: understanding of the role these trees play in local livelihoods. Based on a detailed analysis of smallholder farming systems in southern Honduras and coastal Oaxaca Lessons from the and a botanical survey of trees and shrubs in different land use systems in both study areas, the fi ndings confi rm the importance of involving the local population Mesoamerican dry forest in the management and conservation of Mesoamerican tropical dry forest. The book is directed at researchers in both the socioeconomic and botanical Adrian Barrance, Kathrin Schreckenberg spheres, policy makers at both national and international level, and members of governmental and non-governmental organisations, institutions and projects active and James Gordon in the conservation of tropical dry forest and in rural development in the region. Overseas Development Institute 111 Westminster Bridge Road London SE1 7JD, UK Tel: +44 (0)20 7922 0300 Fax: +44 (0)20 7922 0399 Email: [email protected] Website: www.odi.org.uk ISBN 978-0-85003-894-1 9 780850 038941 Conservation through use: Lessons from the Mesoamerican dry forest Adrian Barrance, Kathrin Schreckenberg and James Gordon This publication is an output from a research project funded by the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of developing countries. -

OECD Territorial Grids

BETTER POLICIES FOR BETTER LIVES DES POLITIQUES MEILLEURES POUR UNE VIE MEILLEURE OECD Territorial grids August 2021 OECD Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions and Cities Contact: [email protected] 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Territorial level classification ...................................................................................................................... 3 Map sources ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Map symbols ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Disclaimers .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Australia / Australie ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Austria / Autriche ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Belgium / Belgique ...................................................................................................................................... 9 Canada ...................................................................................................................................................... -

A Geochemical Study of Four Prehistoric Quarries in Oaxaca, Mexico

A GEOCHEMICAL STUDY OF FOUR PREHISTORIC QUARRIES IN OAXACA, MEXICO. by MICHELLE L. TROGDON (Under the direction of Ervan Garrison) ABSTRACT Petrographic and geochemical analyses of chert quarries used in antiquity for stone tool production in the Mixteca Alta, Oaxaca, Mexico have shown some promising results. This study combines petrography, electron microprobe analysis, hydrofluoric acid treatment, and isotope analysis to identify differences between four quarries and build a database of characteristics associated with each quarry. Major elements in trace amounts (Al, Ca, Na, Mg, and K) and their distribution, fossils, and δ18O values were unable to distinguish unique characteristics of the four quarries presented. However, these methods did reveal interesting information regarding chert formation in general and specific processes that influenced chert formation in Oaxaca. INDEX WORDS: Archaeological Geology, Oaxaca, Mixteca Alta, Chert, Electron Microprobe Analysis, Stable Isotopes. A GEOCHEMICAL STUDY OF FOUR PREHISTORIC QUARRIES IN OAXACA, MEXICO. by MICHELLE L. TROGDON B.S., Allegheny College, 2004 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE ATHENS, GEORGIA 2007 © 2007 MICHELLE L. TROGDON All Rights Reserved A GEOCHEMICAL STUDY OF FOUR PREHISTORIC QUARRIES IN OAXACA, MEXICO. by MICHELLE L. TROGDON Major Professor: Ervan Garrison Committee: Samuel E. Swanson Stephen A. Kowalewski Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia December 2007 DEDICATION To my mother. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to my wonderful committee at the University of Georgia; UGA, Watts- Wheeler, CLACS, SAAS; special thanks to INAH; Dr. Ronald Spores and Dr. -

Herpetofauna Del Cerro Guiengola, Istmo De Tehuantepec, Oaxaca

ISSN 0065-1737 Acta Zoológica MexicanaActa Zool. (n.s.), Mex. 27(2): (n.s.) 359-376 27(2) (2011) HERPETOFAUNA DEL CERRO GUIENGOLA, ISTMO DE TEHUANTEPEC, OAXACA Cintia Natalia MARTÍN-REGALADO,1,2 Rosa Ma. GÓMEZ-UGALDE1 y Ma. Emma CISNEROS-PALACIOS2 1Instituto Tecnológico del Valle de Oaxaca, Ex Hacienda de Nazareno, Xoxocotlán, Oaxaca. C. P. 68000. <[email protected]> 2CIIDIR-IPN. Unidad Oaxaca. Calle Hornos 1003 Xoxocotlán, Oaxaca. Cintia Natalia Martín-Regalado, C. N., R. M. Gómez-Ugalde & M. E. Cisneros-Palacios. 2011. Herpetofauna del Cerro Guiengola, Istmo de Tehuantepec, Oaxaca. Acta Zoológica Mexicana (n. s.), 27(2): 359-376. RESUMEN. Este estudio se realizó en el Cerro Guiengola, Tehuantepec, Oaxaca, con el objetivo de contribuir al conocimiento de la herpetofauna en dicha área. Se obtuvieron 602 registros visuales y se recolectaron 103 ejemplares de anfibios y reptiles durante 60 días de trabajo de campo. Se enlistan 40 especies, pertenecientes a 33 géneros y 18 familias. Se determinó la distribución de la herpetofauna en el Cerro Guiengola por microhábitat, tipo de vegetación y altitud. Usando el método de Jaccard se ela- boraron dendrogramas de similitud por microhábitat y tipo de vegetación. Se reportan especies por tipo de vegetación y rangos altitudinales diferentes a los citados en la literatura. De acuerdo con los valores obtenidos, los índices de diversidad de Simpson y Shannon-Wiener demuestran que el área de estudio es diversa. De las 40 especies que se registraron, 13 son endémicas de México y tres de Oaxaca. El 42.5% de la herpetofauna registrada se encuentra enlistada en la NOM-059-ECOL-2001 y el 47.5% en la Unión Internacional para la Conservación de la Naturaleza (IUCN). -

Social Inequality at Monte Alban Oaxaca: Household Analysis from Terminal Formative to Early Classic

SOCIAL INEQUALITY AT MONTE ALBAN OAXACA: HOUSEHOLD ANALYSIS FROM TERMINAL FORMATIVE TO EARLY CLASSIC by Ernesto González Licón B.A. Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 1982 M.A. Escuela Nacional de Conservación, Restauración y Museografía, 1984 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2003 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Ernesto González Licón It was defended on March 12, 2003 and approved by Dr. Olivier de Montmollin ________________________________ Dr. Marc Bermann ________________________________ Dr. Katheryn Linduff ________________________________ Dr. Robert D. Drennan ________________________________ Committee Chairperson ii Copyright by Ernesto González Licón 2003 iii SOCIAL INEQUALITY AT MONTE ALBAN OAXACA: HOUSEHOLD ANALYSIS FROM TERMINAL FORMATIVE TO EARLY CLASSIC Ernesto González Licón, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2003 The main objective of this dissertation is to reconstruct patterns of social organization and degrees of social stratification in Monte Albán, the capital of the ancient Zapotec state in what is now the state of Oaxaca, Mexico. Social stratification has been defined as the division of a society into categories of individuals organized into hierarchical segments based on access to strategic resources. The study of social stratification is an important aspect to research about the development of complex societies, since stratification has its origin in differential access to strategic resources, and, once the state arises as a form of government, this inequality is institutionalized, and social strata or social classes are formed. This research is based on archaeological data from 12 residential units distributed throughout three different parts of the city and attempts to clarify the composition of the social structure at Monte Albán.