Prelims May 2005.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Workonprogress Work in Progress On

STUDIENWERK Doktorand_innen Jahrbuch 2017 ORK ON PROGRESS WORK INPROGRESS ON Leistungsprinzip Neurose Besatzung Urban Citizenship Partisan*innen Queere Räume Gewalt Positives Denken Ernst Simmel Polittunte Regierungstechniken Ukraine Drone Warfare Biopolitics China Worldmaking Rekolonialisierung Identität Foucault Yugoslavia Neue Frauenbewegung Sentipensar Venezuela Wohnungsgenossenschaft Beiträge kritischer Wissenschaft Herausgegeben von Marcus Hawel & Herausgeber_innen- kollektiv VSA: WORK IN PROGRESS. WORK ON PROGRESS Doktorand_innen-Jahrbuch 2017 der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung WORK IN PROGRESS. WORK ON PROGRESS. Beiträge kritischer Wissenschaft Doktorand_innenjahrbuch 2017 der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Herausgegeben von Marcus Hawel Herausgeber_innenkollektiv: Christine Braunersreuther, Philipp Frey, Sebastian Fritsch, Lucas Pohl und Julia Schwanke VSA: Verlag Hamburg www.vsa-verlag.de Inhalt www.rosalux.de/studienwerk Einleitung: Gewalt und Identität ......................................................... 9 Die Doktorand_innenjahrbücher 2012 (ISBN 978-3-89965-548-3), ZUSAMMENFASSUNGEN .................................................................. 23 2013 (ISBN 978-3-89965-583-4), 2014 (ISBN 978-3-89965-628-2), 2015 (ISBN 978-3-89965-684-8) und 2016 (ISBN 978-3-89965-738-8) der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung sind ebenfalls im VSA: Verlag ERKENNTNISTHEORIE UND METHODIK erschienen und können unter www.rosalux.de als pdf-Datei heruntergeladen werden. Kerstin Meißner Gefühlte Welt_en ............................................................................ -

By Dagmar Schultz AUDRE LORDE – HER STRUGGLES and HER Visionsi in This Presentation I Will Try to Explain How Audre Lorde Came

By Dagmar Schultz AUDRE LORDE – HER STRUGGLES AND HER VISIONSi In this presentation I will try to explain how Audre Lorde came to Germany, what she meant to me personally and to Orlanda Women’s Publishers, and what effect her work had in Germany on Black and white women. In 1980, I met Audre Lorde for the first time at the UN World Women’s Conference in Copenhagen in a discussion following her reading. I knew nothing about her then, nor was I familiar with her books. I was spellbound and very much impressed with the openness with which Audre Lorde addressed us white women. She told us about the importance of her work as a poet, about racism and differences among women, about women in Europe, the USA and South Africa, and stressed the need for a vision of the future to guide our political praxis. On that evening it became clear to me: Audre Lorde must come to Germany for German women to hear her, her voice speaking to white women in an era when the movement had begun to show reactionary tendencies. She would help to pull it out of its provinciality, its over-reliance, in its politics, on the exclusive experience of white women. At that time I was teaching at the Free University of Berlin and thus had the opportunity to invite Audre Lorde to be a guest professor. In the spring of 1984 she agreed to come to Berlin for a semester to teach literature and creative writing. Earlier, in 1981, I had heard Audre Lorde and Jewish poet Adrienne Rich speaking about racism and antisemitism at the National Women’s Studies Association annual convention. -

Khwaja Abdul Hamied

On the Margins <UN> Muslim Minorities Editorial Board Jørgen S. Nielsen (University of Copenhagen) Aminah McCloud (DePaul University, Chicago) Jörn Thielmann (Erlangen University) volume 34 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/mumi <UN> On the Margins Jews and Muslims in Interwar Berlin By Gerdien Jonker leiden | boston <UN> This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Cover illustration: The hiking club in Grunewald, 1934. PA Oettinger, courtesy Suhail Ahmad. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Jonker, Gerdien, author. Title: On the margins : Jews and Muslims in interwar Berlin / by Gerdien Jonker. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, [2020] | Series: Muslim minorities, 1570–7571 ; volume 34 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019051623 (print) | LCCN 2019051624 (ebook) | ISBN 9789004418738 (hardback) | ISBN 9789004421813 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Jews--Germany--Berlin--Social conditions--20th century. | Muslims--Germany--Berlin--Social conditions--20th century. | Muslims --Cultural assimilation--Germany--Berlin. | Jews --Cultural assimilation --Germany--Berlin. | Judaism--Relations--Islam. | Islam --Relations--Judaism. | Social integration--Germany--Berlin. -

Fat Terrorist Bodies

AT ERRORIST ODIES F T B By Lorena D. Espinoza Guerrero Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Erasmus Mundus Master´s Degree in Women´s and Gender Studies (GEMMA) Main Supervisor: Dr. Nadia Jones-Gailani (Central European University) Second Supervisor: Dr. Adelina Sanchez Espinosa (University of Granada) Budapest, Hungary CEU eTD Collection 2020 FAT TERRORIST BODIES By Lorena D. Espinoza Guerrero Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Erasmus Mundus Master´s Degree in Women´s and Gender Studies (GEMMA) Main Supervisor: Dr. Nadia Jones-Gailani (Central European University) Second Supervisor: Dr. Adelina Sanchez Espinosa (University of Granada) Budapest, Hungary 2020 CEU eTD Collection DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is the result of original research; it contains no materials accepted for any other degree in any other institution and no materials previously written and/or published by another person, except where appropriate acknowledgment is made in the form of bibliographical reference. I further declare that the following word count for this thesis are accurate: Body of thesis (all chapters excluding notes, references, appendices, etc.): 32.527 words Entire manuscript: 49.065 words Signed Lorena D. Espinoza Guerrero CEU eTD Collection Abstract Fat, as a socially imposed adjective, contains a myriad of preconceptions and prejudices that have allowed engagements with fat bodies to be problematic at best, violent at worse. Fat bodies, through the construction of the obesity epidemic and the war against fat, have been transformed into dangerous bodies that generate and experience fear. -

AUDRE LORDE: Dream of Europe 90000> SELECTED SEMINARS and INTERVIEWS 1984–1992

ISBN 978-0-9997198-7-9 AUDRE LORDE: dream of europe 90000> SELECTED SEMINARS AND INTERVIEWS 1984–1992 9780999 719879 AUDRE LORDE AUDRE : dream of europe dream of AUDRE LORDE: dream of europe elucidates Lorde’s methodology as a poet, mentor, and activist during the last decade of her life. This volume compiles a series of seminars, interviews, and conversations held by the author and collaborators across Berlin, Western Europe, and The Caribbean between 1984-1992. While Lorde stood at the intersection of various historical and literary movements in The United States—the uprising of black social life after the Harlem Renaissance, poetry of the AIDS epidemic, and the unfolding of the Civil Rights Movement-- this selection of texts reveals Lorde as a catalyst for the first movement of Black Germans in West Berlin. Lorde’s intermittent residence in Berlin lasted for nearly ten years, a period where she inspired many important local and global initiatives, from individual poets to international movements. The legacy of this “Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet” has been well persevered by her colleagues in Germany. It is an erotics of friendship that allowed Lorde and her collaborators EDITIONSKENNING to develop a strong sense of political responsibility for each other, transforming alliance and love Edited, with an afterword between women into tools for social change. These selected writings lay bare struggles, bonds, and by Mayra A. Rodríguez Castro Preface by Dagmar Schultz hopes shared among Black women in a transnational political context. POETRY | POLITICS KENNING EDITIONS POETRY | POLITICS KENNING EDITIONS AUDRE LORDE Lorde_Dream-draft.indd 2-3 11/14/19 8:39 AM DREAM OF EUROPE SELECTED SEMINARS AND INTERVIEWS: 1984-1992 Edited, with an afterword, by Mayra A. -

Audre Lorde: the Berlin Years 1984 to 1992: the Making of the Film and Its Reception

7 C el ebr at i ng Au dr e L or de’s L e gac y 8 dagmar SchultZ Audre Lorde: The Berlin Years 1984 to 1992: The Making of the Film and Its Reception i firsT meT audre lorde in 1980 at the United Nations World Wom- en’s Conference in Copenhagen. At the time I was an assistant profes- sor of North American studies at the Free University of Berlin and in a position to propose Audre for a visiting professorship for a semester. She came to Berlin in 1984 and kept returning until 1992. During these visits, I accompanied Audre to her speaking and teaching engagements, recording her both on audio and videotape, as well as through photog- raphy: Audre considered me her “house photographer.” Sometimes she would even pose for pictures or looked directly into the video camera. It was clear to us both that I would eventually do something with these photos, audiotapes, and video footage. My subsequent film Audre Lorde: The Berlin Years 1984 to 1992 draws on these various recordings, show- ing Audre both on- and offstage and in the many different contexts that made up her life in Berlin. I see the film as a project of “archival activ- ism”—that is, as both a personal, individual, and sociopolitical document and a text that has the potential to generate activism. My goal in making the film was to capture the ability of Audre to empathize with, motivate, and empower women and men. At the same time I hoped to capture and convey the significance that her life in Berlin—and the encounters that she had with Black and white women there —held for her. -

PAPERS Heft 2 Ohne Mohr 18.05.2010 14:45 Uhr Seite 1

PAPERS MARCEL BOIS, BERND HÜTTNER (HRSG.) BEITRÄGE ZUR GESCHICHTE EINER PLURALEN LINKEN THEORIEN UND BEWEGUNGEN NACH 1968 HEFT 2 G STIFTUNG R MBU E LUX sa RO PAPERS_heft 2_ohne mohr 18.05.2010 14:45 Uhr Seite 1 Marcel Bois, Bernd Hüttner (Hrsg.): Beiträge zur Geschichte einer pluralen Linken Theorien und Bewegungen nach 1968 / Heft 2 PAPERS_heft 2_ohne mohr 18.05.2010 14:45 Uhr Seite 2 Impressum: Herausgegeben von der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Franz-Mehring-Platz 1 10243 Berlin www.rosalux.de Diese Publikation kann kostenfrei unter http://www.rosalux.de/publikationen.html heruntergeladen werden. PAPERS_heft 2_ohne mohr 18.05.2010 14:45 Uhr Seite 3 Inhalt Marcel Bois, Bernd Hüttner Zur Einführung 5 Gisela Notz Selbstbestimmung und § 218 7 Gisela Notz Selbstverwaltung und Alternativbewegungen 11 Uwe Sonnenberg Agitation und Aufklärung – Zur Geschichte linker Buchläden nach »1968« 16 Christiane Leidinger Frühe Debatten um Rassismus und Antisemitismus in der (Frauen- und) Lesbenbewegung in den 1980er Jahren der BRD 20 Andreas Heyer Freiheit und genossenschaftlicher Sozialismus in Robert Havemanns »Morgen« 26 Sebastian Gerhardt Die DDR und ihre rebellischen Kinder. Linke Opposition in der Ära Honecker 29 Sebastian Gerhardt Vom Kampf gegen die Politbürokratie zur Verteidigung der DDR. Unabhängige Linke im Kurzen Herbst der Utopie 1989/90 33 Bernd Hüttner Zur Geschichte der Internationalismusbewegung in der Bundesrepublik bis 1992 37 Che 2001 Konjunkturen der Solidarität oder vom Mitgefühl zum Miteinander Zur Geschichte der autonomen Antirassismusgruppen in Deutschland 41 PAPERS_heft 2_ohne mohr 18.05.2010 14:45 Uhr Seite 4 Melanie Groß Gendertrouble und queere Interventionen – Angriffe auf Heterosexismus und Zweigeschlechtlichkeit 44 Harald Rein Keine Atempause – Geschichte wird gemacht … Erwerbslose in Bewegung 48 Nils Schuhmacher »Die Antifa«. -

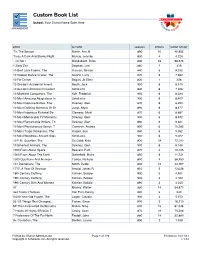

Custom Book List

Custom Book List School: Your District Name Goes Here MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® POINTS WORD COUNT 'Tis The Season Martin, Ann M. 890 10 40,955 'Twas A Dark And Stormy Night Murray, Jennifer 830 4 4,224 ...Or Not? Mandabach, Brian 840 23 98,676 1 Zany Zoo Degman, Lori 860 1 415 10 Best Love Poems, The Hanson, Sharon 840 6 8,332 10 Coolest Dance Crazes, The Swartz, Larry 870 6 7,660 10 For Dinner Bogart, Jo Ellen 820 1 328 10 Greatest Accidental Inventi Booth, Jack 900 6 8,449 10 Greatest American President Scholastic 840 6 7,306 10 Mightiest Conquerors, The Koh, Frederick 900 6 8,034 10 Most Amazing Adaptations In Scholastic 900 6 8,409 10 Most Decisive Battles, The Downey, Glen 870 6 8,293 10 Most Defining Moments Of Th Junyk, Myra 890 6 8,477 10 Most Ingenious Fictional De Clemens, Micki 870 6 8,687 10 Most Memorable TV Moments, Downey, Glen 900 6 8,912 10 Most Remarkable Writers, Th Downey, Glen 860 6 9,321 10 Most Revolutionary Songs, T Cameron, Andrea 890 6 10,282 10 Most Tragic Romances, The Harper, Sue 860 6 9,052 10 Most Wondrous Ancient Sites Scholastic 900 6 9,022 10 P.M. Question, The De Goldi, Kate 830 18 72,103 10 Smartest Animals, The Downey, Glen 900 6 8,148 1000 Facts About Space Beasant, Pam 870 4 10,145 1000 Facts About The Earth Butterfield, Moira 850 6 11,721 1000 Questions And Answers Tames, Richard 890 9 38,950 101 Dalmatians, The Smith, Dodie 830 12 44,767 1777: A Year Of Decision Arnold, James R. -

Angelo Soliman Then and Now: a Historical and Psychoanalytical Interpretation of Soliman Depictions in Modern German Literature

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2006 Angelo Soliman Then and Now: A Historical and Psychoanalytical Interpretation of Soliman Depictions in Modern German Literature Erin Elizabeth Read Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the German Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Read, Erin Elizabeth, "Angelo Soliman Then and Now: A Historical and Psychoanalytical Interpretation of Soliman Depictions in Modern German Literature. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2006. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1774 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Erin Elizabeth Read entitled "Angelo Soliman Then and Now: A Historical and Psychoanalytical Interpretation of Soliman Depictions in Modern German Literature." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in German. Stefanie Ohnesorg, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Olaf Berwald, Carolyn Hodges Accepted for -

The Transatlantic Sixties

Grzegorz Kosc, Clara Juncker, Sharon Monteith, Britta Waldschmidt-Nelson (eds.) The Transatlantic Sixties Volume 4 The series America: Culture – History – Politics is edited by Christof Mauch, Michael Hochgeschwender, Anke Ortlepp, Ursula Prutsch, and Britta Waldschmidt-Nelson. Grzegorz Kosc, Clara Juncker, Sharon Monteith, Britta Waldschmidt-Nelson (eds.) The Transatlantic Sixties Europe and the United States in the Counterculture Decade This book is published with the generous support of the German Historical Insti- tute Washington, DC, the Lasky Center for Transatlantic Studies at the University of Munich, and the University of Southern Denmark. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative ini- tiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 (BY-NC-ND). which means that the text may be used for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Natio- nalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or uti- lized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

CENTER for the HUMANITIES UC BERKELEY September/October 2012 HIGHLIGHTS

TOWNSENDCENTER FOR THE HUMANITIES UC BERKELEY September/October 2012 HIGHLIGHTS 21 Fiat Lux Redux 22 Depth of Field Film + Video Series 26 Litquake: Language and Politics Vikram Seth, see p. 6 Wendell Berry, see p. 4 TOWNSEND NEWSLETTER The Doreen B. Townsend Center for the Humanities SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2012 at the University of California, Berkeley STAFF DIRECTOR Alan Tansman, Professor of Japanese TABLE OF CONTENTS ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR Teresa Stojkov 3 A Note from the New Director WEB AND COMMUNICATIONS SPECIALIST Alan Tansman Julie Van Scoy BUSINESS AND OFFICE MANAGER 4 Labor of the Hands Melissa Wong Juliana Chow FELLOWSHIPS ADMINISTRATOR Scott Roberts 6 Vikram Seth, Una's Lecturer Kristin Hanson FACULTY ADVISORY COMMITTEE David Bates, Rhetoric 8 Visions from the Peripheries Lawrence Cohen, Anthropology Jacob P. Dalton Catherine Cole, eater, Dance & Performance Studies 11 Program News Victoria Kahn, English Ken Goldberg, Industrial Engineering and Operations Research Suzanne Guerlac, French 17 Calendar of Campus Events Niklaus Largier, German and Comparative Literature Francine Masiello, Spanish and Comparative Literature Nancy Scheper-Hughes, Anthropology Hans Sluga, Philosophy Mary Ann Smart, Music TOWNSEND CENTER FOR THE HUMANITIES University of California 220 Stephens Hall, MC 2340 Berkeley, CA 94720-2340 TEL.: 510/643-9670 FAX: 510/643-5284 EMAIL: [email protected] WEB: http://townsendcenter.berkeley.edu TOWNSEND CENTER FOR THE HUMANITIES | SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2012 A Note from the New Director by Alan Tansman groups will be formed in particular to foster conversations between humanists and their non-humanist colleagues. You will be hearing more about these groups in the coming months, and we, in turn, look forward to learning of your ideas about creating others. -

“Crisis” After Cologne: the Race of Refugee Rights1

The German Refugee “Crisis” after Cologne: The Race of Refugee Rights1 Beverly Weber n early January 2016, violence at the Cologne train station on New Year’s Eve drew tremendous attention from the German and international public. Over one thousand men Ireportedly descended on the central train station, in a convergence initially thought to be spurred by social media calls. Widespread theft and groping were reported to the police, with several white German women recounting being surrounded by groups of men described as looking “North African” or “Arab.” A few weeks later, the German parliament held a parliamentary debate entitled “Konsequenzen aus der Ereignissen von Köln und anderen Großstädten in der Silvesternacht” [Consequences of the Events in Cologne and other Large Cities on New Year’s Eve]. This parliamentary debate constitutes a unique moment in the discursive construction and representation of immigrants and refugees in Germany today. Despite the extremity of the reaction to these events on the part of populist radical right groups, as well as the con- tradictory and conflicted media response, nearly all of the speakers during the parliamen- tary debate cautioned against rhetoric that would reductively identify all (male) refugees as sexual perpetrators; many parliamentarians also highlighted the importance of recognizing neo-Nazi “hooligans” and other perpetrators of right violence as equal threats to public space. This effort to frame the debate in a non-racist way provides a marked contrast to the language and debates informing recent German engagements with race, refugees, and immi- gration, such as the headscarf debates of the early 2000s, which often imagined Muslim men in particular as inherently violent.