Khwaja Abdul Hamied

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Family Business Briefs Issue 62 / October 2020

Family Business Briefs Issue 62 / October 2020 Welcome! I am delighted to share with you the latest issue of our newsletter, 'Family Business Briefs.' This issue contains some interesting facts and information about family businesses that you may find useful. The briefs have been organized into the following sections: • Summaries of research articles with practical implications on Next Generation’s External Venturing Practices, Role Transitions in Multiplex Relationships, and Corporate Political Activity of Family Firms • Summary of a family business case on Annapurna Studios • Inspirations from the life of Khwaja Abdul Hamied • Interesting insights on Malaxmi Group • Infographic on Women in Family Business: Towards Gender Parity We hope that you will find these insightful and invigorating. I encourage you to send your feedback and share suggestions about something interesting and relevant, which you may want us to include in future. Best regards Ram Kavil Ramachandran, PhD Professor & Executive Director Thomas Schmidheiny Centre for Family Enterprise Indian School of Business ARTICLE SUMMARY Next Generation External Venturing Practices in Family Owned Businesses - Marcela Ramírez-Pasillas, Hans Lundberg, and Mattias Nordqvist Family businesses create new ventures to family and obtaining their agreement. develop a business portfolio and promote 2. Bypassing Family: Diverting family transgenerational entrepreneurship. However, attention and using / misusing family trust. there is little understanding of how the next 3. Family Venture Mimicking: Relating with generation members managing a venture that the family’s venture model and copying its is distant from the family's core business, venture creation activities. interact with other family members to advance their venture. This study examined the 4. -

Edelgive Hurun India Philanthropy List 2020 10 November 2020

EDELGIVE HURUN INDIA PHILANTHROPY LIST 2020 10 NOVEMBER 2020 Press Release Report EdelGive Hurun India Philanthropy List 2020 Key Highlights WITH A DONATION OF INR 7,904 CRORE, AZIM PREMJI,75, WAS ‘INDIA’S MOST GENEROUS’. HE DONATED INR 22 CRORES PER DAY! HCL’S SHIV NADAR, 75, WAS SECOND WITH INR 795 CRORE DONATION WITH A DONATION OF INR 27 CRORE, AMIT CHANDRA,52, AND ARCHANA CHANDRA, 49, OF A.T.E. CHANDRA FOUNDATION ARE THE FIRST AND ONLY PROFESSIONAL MANAGERS TO EVER ENTER THE EDELGIVE HURUN INDIA PHILANTHROPY LIST. INDIAN PHILANTHROPY STATS AT A RECORD HIGH; NO. OF INDIVIDUALS WHO HAVE DONATED MORE THAN INR 10 CRORE INCREASED BY 100% OVER THE LAST 2 YEARS, FROM 37 TO 78 THIS YEAR LED BY SD SHIBULAL, 65, WHO DONATED INR 32 CRORES, 28 NEW ADDITIONS TO THE LIST; TOTAL DONATIONS BY NEW ADDITIONS AT INR 313 CRORE WITH A DONATION OF INR 458 CRORE, INDIA’S RICHEST MAN, MUKESH AMBANI,63, CAME THIRD WITH A DONATION OF INR 276 CRORE, KUMAR MANGALAM BIRLA, 53, OF ADITYA BIRLA GROUP DEBUTS THE TOP 5 AND IS THE YOUNGEST IN TOP 10 YOUNGEST: BINNY BANSAL, 37, DEBUTED THE EDELGIVE HURUN INDIA PHILANTHROPY LIST WITH A DONATION OF INR 5.3 CRORES WITH 90 PHILANTHROPISTS CUMULATIVELY DONATING INR 9,324 CRORES, EDUCATION THE MOST FAVOURED CAUSE. WITH 84 DONORS, HEALTHCARE REGISTERED A 111% INCREASE IN CUMULATIVE DONATION, FOLLOWED BY DISASTER RELIEF & MANAGEMENT, WHICH HAD 41 DONORS, REGISTERING A CUMULATIVE DONATION OF INR 354 CRORES OR AN INCREASE OF 240% 3 OF INFOSYS’S CO-FOUNDERS MADE THE LIST, WITH NANDAN NILEKANI, S GOPALAKRISHNAN AND SD SHIBULAL, -

The Orientalist: Solving the Mystery of a Strange and Dangerous Life Pdf

FREE THE ORIENTALIST: SOLVING THE MYSTERY OF A STRANGE AND DANGEROUS LIFE PDF Tom Reiss | 447 pages | 22 Sep 2006 | Random House USA Inc | 9780812972764 | English | New York, United States The Orientalist by Tom Reiss: | : Books Account Options Sign in. Top charts. New arrivals. Tom Reiss Feb Switch to the audiobook. Part history, part cultural biography, and part literary mystery, The Orientalist traces the life of Lev Nussimbaum, a Jew who transformed himself into a Muslim prince and became a best-selling author in Nazi Germany. Born in to a wealthy family in the oil-boom city of Baku, at the edge of the czarist empire, Lev escaped the Russian Revolution in a camel caravan. He found refuge in Germany, where, writing under the names Essad Bey and Kurban Said, his remarkable books about Islam, desert adventures, The Orientalist: Solving the Mystery of a Strange and Dangerous Life global revolution, became celebrated across fascist Europe. His enduring masterpiece, Ali and Nino —a story of love across ethnic and religious boundaries, published on the eve of the Holocaust—is still in print today. He married an international heiress who had no idea of his true identity—until she divorced him in a tabloid scandal. Under house arrest in the Amalfi cliff town of Positano, Lev wrote his The Orientalist: Solving the Mystery of a Strange and Dangerous Life book—discovered in a half a dozen notebooks never before read by anyone—helped by a mysterious half-German salon hostess, an Algerian weapons-smuggler, and the poet Ezra Pound. Tom Reiss spent five years tracking down secret police records, love letters, diaries, and the deathbed notebooks. -

Shifting Paradigm

SHIFTING PARADIGM How the BRICS Are Reshaping Global Health and Development ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was developed by Global Health Strategies initiatives (GHSi), an international nonprofit organization advocating for improved access to health technologies and services in developing countries. Our efforts engaged the expertise of our affiliate, Global Health Strategies, an international consultancy with offices in New York, Delhi and Rio de Janeiro. This report comprises part of a larger project focused on the intersections between major growth economies and global health efforts, supported by a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. GHSi senior leadership, who advised the team throughout development of this report, includes David Gold and Victor Zonana (New York), Anjali Nayyar (Delhi) and Alex Menezes (Rio de Janeiro). Brad Tytel, who directs GHSi’s work on growth economies and global health, led the development of the report. Katie Callahan managed the project and led editorial efforts. Chandni Saxena supervised content development with an editorial team, including: Nidhi Dubey, Chelsea Harris, Benjamin Humphrey, Chapal Mehra, Daniel Pawson, Jennifer Payne, Brian Wahl. The research team included the following individuals, however contents do not necessarily reflect the opinions of their respective institutions: Brazil Carlos Passarelli, Senior Advisor, Treatment Advocacy, UNAIDS Cristina Pimenta, Associate Professor, School of Biological Sciences, Veiga de Almeida University Russia Kirill Danishevskiy, Assistant Professor, -

Ignaz Goldziher Example

147-105 :5 ,2020 / ديسمبر / Aralık / December A Study on the Historical Foundations of Jewish Orientalism: Ignaz Goldziher Example Yahudi Oryantalizminin Tarihi Temelleri Üzerine Bir Araştırma: Ignaz Goldziher Örneği دراسة حول ا ألسس التارخيية لﻻسترشاق الهيودي: اجنا س جودلتس هير منوذج ا Hafize Yazıcı Arş. Gör. Atatürk Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi, Erzurum/Türkiye Res. Ast., Ataturk University Faculty of Theology, Erzurum/Turkey [email protected] ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6675-5890 Makale Bilgisi | Article Information Makalenin Türü / Article Type : Araştırma Makalesi / Research Article Geliş Tarihi / Received Date: 12.12.2020 Kabul Tarihi / Accepted Date: 30.12.2020 Yayın Tarihi / Published Date: 31.12.2020 Yayın Sezonu / Publication Date Season: Aralık / December DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4429234 Yazıcı, Hafize. “A Study on the Historical Foundations of Jewish Orientalism: Ignaz Goldziher : ا قتباس / Atıf / Citation Example / Yahudi Oryantalizminin Tarihi Temelleri Üzerine Bir Araştırma: Ignaz Goldziher Örneği”. HADITH 5 (Aralık/December 2020): 105-147. doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4429234. İntihal: Bu makale, iTenticate yazılımınca taranmıştır. İntihal tespit edilmemiştir. Plagiarism: This article has been scanned by iThenticate. No plagiarism has been detected. انتحال: مت فحص البحث بواسطة برانمج ﻷجل السرقة العلمية فلم يتم إجياد أي سرقة علمية. web: http://dergipark.gov.tr/hadith | mailto: [email protected] HADITH 5 (Aralık/December 2020): 105-147 A Study on the Historical Foundations of Jewish Orientalism: Ignaz Goldziher Example Hafize YAZICI Keywords: ABSTRACT Jewish Orientalism While Christians had a long history of Islamic Studies in the West, Jewish also made remarkable Islām contributions to this field beginning from the early periods, and they have had a pioneering role Judaism in this field thanks to the scientists they educated. -

Tracing, Cataloguing, Indexing: Reflections on the Joachim And

A R C H I V A L Reflexicon 2019 Entangled Institutional and Affective Archives of South Asian Muslim Students in Germany Razak Khan, Postdoctoral Fellow, MIDA, CeMIS (Göttingen University) Introduction: Institutions, Actors and Networks The Archiv der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin located at Wagner-Régeny-Straße 5, 12489 Berlin1, provides useful information about intellectual entanglements spread across educational connections at the University. In this brief post, I examine some archival sources pertaining to South Asian students to make a case for entangling archives of educational institutions with the personal biographical affective archives to explore creative intellectual entanglements. My focus will be on South Asian Muslim students whom we encounter both in institutional archives as well as in rich affective biographical accounts left behind by them. The Humboldt-Universität’s archival collection is undergoing digitization and is now searchable through finding aids and online archival data search. https://www.archiv-hu berlin.findbuch.net However, the generic keyword search on India and Indians is not very fruitful. It is better to use the German keyword Ausländer as well as Indien/Inder/indisch. A search conducted with these keywords leads to general results and not specific ones. However, documents on individuals can be accessed if adequate details like full name and year of study are provided to archivists. I was able to find information about Indian students in an un-catalogued selection of cards Ausländerkartei Indien, 1928-1938, The Humboldt- Universität zu Berlin archive. The archivist provided me with student cards that have been assembled prior to the digitization project. These enrollment cards are the most important source of information, especially about Indian students who registered with the Deutsches Institut für Ausländer (German Institute for Foreigners) for study-related issues, particularly German language-learning (See appendix for the full list). -

V.Karin Weirauch Und Jürgen Protzen)

Bericht zur Tagestour des TVN am 24.10.2009 (v.Karin Weirauch und Jürgen Protzen) Am Samstag, 24.20.2009, fand die diesjährige Kulturfahrt des TV Niederbieber als Halbtagestour statt. Auch diesmal war es wieder eine Fahrt ins Blaue. Mit zwei Bussen fuhren wir erst mal zur A 61, wo wir auch eine Weile draufblieben. Alle waren gespannt, wo es denn diesmal hingehen wird. Von der Autobahn fuhren wir runter durch die wunderschöne herbstliche Eifel. Immerzu ging es in Richtung Aachen. Somit lag der Verdacht nahe, dass es vielleicht dorthin geht. Wir fuhren jedoch an Blankenheim und Schleiden vorbei, bis wir dann abbogen. Also ging es doch nicht Aachen, wie wohl viele dachten. Im Nationalpark Eifel besuchten wir das denkmalgeschützte Ensemble Vogelsang. Inmitten der entstehenden Nationalpark-Wildnis liegt Vogelsang. Die rund 100 Hektar große Anlage wurde ab 1934 als Schulungsstätte des national-sozialistischen Regimes errichtet. Hier wurden junge Männer auf ihre Rolle als zukünftige Führungselite für die verbrecherischen Ziele der NSDAP ausgebildet. Nach Ende des Zweiten Weltkrieges dienten die Gebäude bis 2005 als Kaserne des umliegenden Truppenübungsplatzes. Heute entwickelt sich Vogelsang zu einem internationalen Treffpunkt, der Information, Erholung und vielfältiges Lernen bietet. Durch eine interessante Führung erfuhren wir eine Menge von dieser schlimmen Zeit. Danach wurde ein Gemeinschaftsfoto gemacht und anschließend zur Weiterfahrt wieder die Busse bestiegen. In Schleiden-Gemünd im „Alten Rathaus“ waren zum gemeinsamen Kaffeetrinken Tische für uns alle bestellt. Gegen 17:30 Uhr traten wir die Heimfahrt an. Den Abschluss, auch bis zum Schluss geheimgehalten, hatten wir in der „Waldterrasse“ in Rengsdorf bei gutem Essen und gemütlichen Zusammensein. -

Top 200+ Current Affairs Monthly MCQ's September

Facebook Page Facebook Group Telegram Group Telegram Channel AMBITIOUSBABA.COM | ONLINE TEST SERIES: TEST.AMBITIOUSBABA.COM | MAIL 1 US AT [email protected] Facebook Page Facebook Group Telegram Group Telegram Channel Q1.India's first-ever sky cycling park to be opened in which city? (a) Manali (b) Mussoorie (c) Nainital (d) Shimla (e) None of these Ans.1.(a) Exp.To boost tourism and give and an all new experience to visitors, India's first-ever sky cycling park will soon open at Gulaba area near Manali in Himachal Pradesh. It is 350m long & is located at a height of 9000 Feet above sea level. Forest Department and Atal Bihari Vajpayee Institute of Mountaineering and Allied Sports have jointly developed an eco-friendly park. AMBITIOUSBABA.COM | ONLINE TEST SERIES: TEST.AMBITIOUSBABA.COM | MAIL 2 US AT [email protected] Facebook Page Facebook Group Telegram Group Telegram Channel Q2.Which sportsperson has won the 2019 Rashtriya Khel Protsahan Puraskar? (a) Abhinav Bindra (b) Jeev Milkha Singh (c) Mary Kom (d) Gagan Narang (e) None of these Ans.2.(d) Exp.On 2019 National Sports Day (NSD), Gagan Narang and Pawan Singh have been honoured with the Rashtriya Khel Protsahan Puraskar for their Gagan Narang Sports Promotion Foundation (GNSPF) at the Arjuna Awards ceremony in Rashtrapati Bhavan, New Delhi. The award recognizes their contribution in the growth of their favourite sport and a reward for sacrifices they have made to realize their dream. In 2011, Narang and co-founder Pawan Singh founded GNSPF to nurture budding talent -

MB Heft 2 2020

MÜNCHNER BEITRÄGE ZUR JÜDISCHEN GESCHICHTE UND KULTUR Abteilung für Jüdische Geschichte und Kultur an der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München BEGEGNUNGEN. JUDEN UND MUSLIME IM DEUTSCH- LAND DER ZWISCHENKRIEGSZEIT Beiträge von Marc David Baer, Gerdien Jonker, Sabine Mangold-Will, David Motadel und Ronen Steinke Jg. 14 / Heft 2 ∙ 2020 Dieses Heft wurde gefördert von der Israelitischen Kultusgemeinde München und Oberbayern und vom Freundeskreis des Lehrstuhls für Jüdische Geschichte und Kultur an der Ludwig-Maximilians- Universität München e.V. Herausgeber: Abteilung für Jüdische Geschichte und Kultur, Michael Brenner Beirat: Martin Baumeister, Rom – Menahem Ben-Sasson, Jerusalem – Richard I. Cohen, Jerusalem – John M. Efron, Berkeley – Jens Malte Fischer, München – Benny Morris, Beer Sheva – Ronny Vollandt, München – Ada Rapoport-Albert (sel. A.), London – David B. Ruderman, Philadelphia – Martin Schulze Wessel, München – Avinoam Shalem, New York – Wolfram Siemann, München – Alan E. Steinweis, Vermont – Norman Stillman, Oklahoma – Yfaat Weiss, Jerusalem/Leipzig – Stephen J. Whitfield, Brandeis. Redaktion: Eva Haverkamp-Rott, Hiltrud Häntzschel, Philipp Lenhard (verantwortlich), Daniel Mahla, Martina Niedhammer, Norbert Ott, Julia Schneidawind, Evita Wiecki, Ernst-Peter Wieckenberg Anschrift: Abteilung für Jüdische Geschichte und Kultur an der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Historisches Seminar, Geschwister-Scholl-Platz 1, 80539 München. e-mail: [email protected] Erscheinungsweise: Jährlich zwei Hefte. Bezugsbedingungen: Die Zeitschrift wird gegen eine Schutzgebühr von 10,00 € je Einzelheft, von 18 € im Jahresabonnement, zzgl. Porto abgegeben. Bestellungen werden an die Abteilung erbeten. Manuskripte: Die Redaktion haftet nicht für unverlangt eingesandte Manuskripte. Umschlagabbildung Bildnachweis: Creative Commons; Privatarchiv Julia Schweisthal Trotz intensiver Bemühungen war es dem Herausgeber nicht möglich, alle Rechteinhaber der verwendeten Bilder zu ermitteln. -

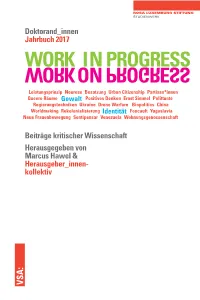

Workonprogress Work in Progress On

STUDIENWERK Doktorand_innen Jahrbuch 2017 ORK ON PROGRESS WORK INPROGRESS ON Leistungsprinzip Neurose Besatzung Urban Citizenship Partisan*innen Queere Räume Gewalt Positives Denken Ernst Simmel Polittunte Regierungstechniken Ukraine Drone Warfare Biopolitics China Worldmaking Rekolonialisierung Identität Foucault Yugoslavia Neue Frauenbewegung Sentipensar Venezuela Wohnungsgenossenschaft Beiträge kritischer Wissenschaft Herausgegeben von Marcus Hawel & Herausgeber_innen- kollektiv VSA: WORK IN PROGRESS. WORK ON PROGRESS Doktorand_innen-Jahrbuch 2017 der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung WORK IN PROGRESS. WORK ON PROGRESS. Beiträge kritischer Wissenschaft Doktorand_innenjahrbuch 2017 der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Herausgegeben von Marcus Hawel Herausgeber_innenkollektiv: Christine Braunersreuther, Philipp Frey, Sebastian Fritsch, Lucas Pohl und Julia Schwanke VSA: Verlag Hamburg www.vsa-verlag.de Inhalt www.rosalux.de/studienwerk Einleitung: Gewalt und Identität ......................................................... 9 Die Doktorand_innenjahrbücher 2012 (ISBN 978-3-89965-548-3), ZUSAMMENFASSUNGEN .................................................................. 23 2013 (ISBN 978-3-89965-583-4), 2014 (ISBN 978-3-89965-628-2), 2015 (ISBN 978-3-89965-684-8) und 2016 (ISBN 978-3-89965-738-8) der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung sind ebenfalls im VSA: Verlag ERKENNTNISTHEORIE UND METHODIK erschienen und können unter www.rosalux.de als pdf-Datei heruntergeladen werden. Kerstin Meißner Gefühlte Welt_en ............................................................................ -

By Dagmar Schultz AUDRE LORDE – HER STRUGGLES and HER Visionsi in This Presentation I Will Try to Explain How Audre Lorde Came

By Dagmar Schultz AUDRE LORDE – HER STRUGGLES AND HER VISIONSi In this presentation I will try to explain how Audre Lorde came to Germany, what she meant to me personally and to Orlanda Women’s Publishers, and what effect her work had in Germany on Black and white women. In 1980, I met Audre Lorde for the first time at the UN World Women’s Conference in Copenhagen in a discussion following her reading. I knew nothing about her then, nor was I familiar with her books. I was spellbound and very much impressed with the openness with which Audre Lorde addressed us white women. She told us about the importance of her work as a poet, about racism and differences among women, about women in Europe, the USA and South Africa, and stressed the need for a vision of the future to guide our political praxis. On that evening it became clear to me: Audre Lorde must come to Germany for German women to hear her, her voice speaking to white women in an era when the movement had begun to show reactionary tendencies. She would help to pull it out of its provinciality, its over-reliance, in its politics, on the exclusive experience of white women. At that time I was teaching at the Free University of Berlin and thus had the opportunity to invite Audre Lorde to be a guest professor. In the spring of 1984 she agreed to come to Berlin for a semester to teach literature and creative writing. Earlier, in 1981, I had heard Audre Lorde and Jewish poet Adrienne Rich speaking about racism and antisemitism at the National Women’s Studies Association annual convention. -

Prelims May 2005.Qxd

German Historical Institute London Bulletin Bd. 27 2005 Nr. 1 Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Stiftung Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hinausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weitergabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich verfolgt werden. REVIEW ARTICLES GERMANS AND BLACKS—BLACK GERMANS by Matthias Reiss MICHAEL SCHUBERT, Der schwarze Fremde: Das Bild des Schwarz- afrikaners in der parlamentarischen und publizistischen Kolonialdiskussion in Deutschland von den 1870er bis in die 1930er Jahren, Beitäge zur Ko- lonial- und Überseegeschichte, 86 (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2003), 446 pp. ISBN 3 515 08267 0. EUR 79.00 TINA M. CAMPT, Other Germans: Black Germans and the Politics of Race, Gender, and Memory in the Third Reich, Social History, Popular Culture, and Politics in Germany (Ann Arbor: University of Michig- an Press, 2004), x + 283 pp. ISBN 0 472 11360 7. $ 29.95 MARIANNE BECHHAUS-GERST and REINHARD KLEIN-ARENDT (eds.), AfrikanerInnen in Deutschland und schwarze Deutsche: Geschichte und Gegenwart, Encounters. History and Present of the African–Euro- pean Encounter/Begegnungen. Geschichte und Gegenwart der afri- kanisch-eruopäischen Begegnung, 3 (Münster: Lit Verlag, 2004), 261 pp. ISBN 3 8258 6824 9. EUR 20.90 In June 1972, the Allensbach Institut für Demoskopie conducted a poll on what the Germans thought about ‘the Negroes’ (die Neger).