225 Introduction: the Roots of Modern Racism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The European and Russian Far Right As Political Actors: Comparative Approach

Journal of Politics and Law; Vol. 12, No. 2; 2019 ISSN 1913-9047 E-ISSN 1913-9055 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The European and Russian Far Right as Political Actors: Comparative Approach Ivanova Ekaterina1, Kinyakin Andrey1 & Stepanov Sergey1 1 RUDN University, Russia Correspondence: Stepanov Sergey, RUDN University, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] Received: March 5, 2019 Accepted: April 25, 2019 Online Published: May 30, 2019 doi:10.5539/jpl.v12n2p86 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/jpl.v12n2p86 The article is prepared within the framework of Erasmus+ Jean Monnet Module "Transformation of Social and Political Values: the EU Practice" (575361-EPP-1-2016-1-RU-EPPJMO-MODULE, Erasmus+ Jean Monnet Actions) (2016-2019) Abstract The article is devoted to the comparative analysis of the far right (nationalist) as political actors in Russia and in Europe. Whereas the European far-right movements over the last years managed to achieve significant success turning into influential political forces as a result of surging popular support, in Russia the far-right organizations failed to become the fully-fledged political actors. This looks particularly surprising, given the historically deep-rooted nationalist tradition, which stems from the times Russian Empire. Before the 1917 revolution, the so-called «Black Hundred» was one of the major far-right organizations, exploiting nationalistic and anti-Semitic rhetoric, which had representation in the Russian parliament – The State Duma. During the most Soviet period all the far-right movements in Russia were suppressed, re-emerging in the late 1980s as rather vocal political force. But currently the majority of them are marginal groups, partly due to the harsh party regulation, partly due to the fact, that despite state-sponsored nationalism the position of Russian far right does not stand in-line with the position of Russian authorities, trying to suppress the Russian nationalists. -

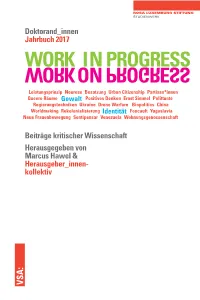

Workonprogress Work in Progress On

STUDIENWERK Doktorand_innen Jahrbuch 2017 ORK ON PROGRESS WORK INPROGRESS ON Leistungsprinzip Neurose Besatzung Urban Citizenship Partisan*innen Queere Räume Gewalt Positives Denken Ernst Simmel Polittunte Regierungstechniken Ukraine Drone Warfare Biopolitics China Worldmaking Rekolonialisierung Identität Foucault Yugoslavia Neue Frauenbewegung Sentipensar Venezuela Wohnungsgenossenschaft Beiträge kritischer Wissenschaft Herausgegeben von Marcus Hawel & Herausgeber_innen- kollektiv VSA: WORK IN PROGRESS. WORK ON PROGRESS Doktorand_innen-Jahrbuch 2017 der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung WORK IN PROGRESS. WORK ON PROGRESS. Beiträge kritischer Wissenschaft Doktorand_innenjahrbuch 2017 der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Herausgegeben von Marcus Hawel Herausgeber_innenkollektiv: Christine Braunersreuther, Philipp Frey, Sebastian Fritsch, Lucas Pohl und Julia Schwanke VSA: Verlag Hamburg www.vsa-verlag.de Inhalt www.rosalux.de/studienwerk Einleitung: Gewalt und Identität ......................................................... 9 Die Doktorand_innenjahrbücher 2012 (ISBN 978-3-89965-548-3), ZUSAMMENFASSUNGEN .................................................................. 23 2013 (ISBN 978-3-89965-583-4), 2014 (ISBN 978-3-89965-628-2), 2015 (ISBN 978-3-89965-684-8) und 2016 (ISBN 978-3-89965-738-8) der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung sind ebenfalls im VSA: Verlag ERKENNTNISTHEORIE UND METHODIK erschienen und können unter www.rosalux.de als pdf-Datei heruntergeladen werden. Kerstin Meißner Gefühlte Welt_en ............................................................................ -

By Dagmar Schultz AUDRE LORDE – HER STRUGGLES and HER Visionsi in This Presentation I Will Try to Explain How Audre Lorde Came

By Dagmar Schultz AUDRE LORDE – HER STRUGGLES AND HER VISIONSi In this presentation I will try to explain how Audre Lorde came to Germany, what she meant to me personally and to Orlanda Women’s Publishers, and what effect her work had in Germany on Black and white women. In 1980, I met Audre Lorde for the first time at the UN World Women’s Conference in Copenhagen in a discussion following her reading. I knew nothing about her then, nor was I familiar with her books. I was spellbound and very much impressed with the openness with which Audre Lorde addressed us white women. She told us about the importance of her work as a poet, about racism and differences among women, about women in Europe, the USA and South Africa, and stressed the need for a vision of the future to guide our political praxis. On that evening it became clear to me: Audre Lorde must come to Germany for German women to hear her, her voice speaking to white women in an era when the movement had begun to show reactionary tendencies. She would help to pull it out of its provinciality, its over-reliance, in its politics, on the exclusive experience of white women. At that time I was teaching at the Free University of Berlin and thus had the opportunity to invite Audre Lorde to be a guest professor. In the spring of 1984 she agreed to come to Berlin for a semester to teach literature and creative writing. Earlier, in 1981, I had heard Audre Lorde and Jewish poet Adrienne Rich speaking about racism and antisemitism at the National Women’s Studies Association annual convention. -

Khwaja Abdul Hamied

On the Margins <UN> Muslim Minorities Editorial Board Jørgen S. Nielsen (University of Copenhagen) Aminah McCloud (DePaul University, Chicago) Jörn Thielmann (Erlangen University) volume 34 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/mumi <UN> On the Margins Jews and Muslims in Interwar Berlin By Gerdien Jonker leiden | boston <UN> This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Cover illustration: The hiking club in Grunewald, 1934. PA Oettinger, courtesy Suhail Ahmad. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Jonker, Gerdien, author. Title: On the margins : Jews and Muslims in interwar Berlin / by Gerdien Jonker. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, [2020] | Series: Muslim minorities, 1570–7571 ; volume 34 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019051623 (print) | LCCN 2019051624 (ebook) | ISBN 9789004418738 (hardback) | ISBN 9789004421813 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Jews--Germany--Berlin--Social conditions--20th century. | Muslims--Germany--Berlin--Social conditions--20th century. | Muslims --Cultural assimilation--Germany--Berlin. | Jews --Cultural assimilation --Germany--Berlin. | Judaism--Relations--Islam. | Islam --Relations--Judaism. | Social integration--Germany--Berlin. -

Inventory of the Private Collection of HF Verwoerd PV93

Inventory of the private collection of HF Verwoerd PV93 Contact us Write to: Visit us: Archive for Contemporary Affairs Archive for Contemporary Affairs University of the Free State Stef Coetzee Building P.O. Box 2320 Room 109 Bloemfontein 9300 Academic Avenue South South Africa University of the Free State 205 Nelson Mandela Drive Park West Bloemfontein Telephone: Email: +27(0)51 401 2418/2646/2225 [email protected] PV93 Dr HF Verwoerd FILE NO SERIES SUB-SERIES DESCRIPTION DATES 1/1/1 1. SUBJECT 1/1 Afrikaner Correspondence regarding the Ossewa 1939-1947 FILES unity movements Brandwag-movement, Dr D.F. Malan's rejection of the Ossewa Brandwag- movement and National-Socialistic attitudes; the New Order-movement of Adv. Oswald Pirow; plea for the acknowledgement of Gen. J.B.M. Hertzog as Afrikaner leader in order to sustain Afrikaner- unity; Dr Verwoerd's view as chief editor of Die Transvaler regarding reporting on the Ossewa Brandwag-movement and tie Opposition; notes of Dr Verwoerd regarding the enmity between the leaders of the Ossewa Brandwag and the National Party; minutes of meetings concerning Afrikaner-unity. 1/1/2 1. SUBJECT 1/1 Afrikaner Cuttings regarding Gen. E.A. Conroy on 1941-1942 FILES unity movements the future of the Afrikaner Party after the war; Dr J.F.J. Van Rensburg, leader of the Ossewa Brandwag, concerning republicanism; Adv. Oswald Pirow and the New Order Party; differences of opinion between the Re-united Party and the Ossewa Brandwag-movement and the rejection of the political ideals of the Ossewa Brandwag 1/1/3 1. -

Prelims May 2005.Qxd

German Historical Institute London Bulletin Bd. 27 2005 Nr. 1 Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Stiftung Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hinausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weitergabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich verfolgt werden. REVIEW ARTICLES GERMANS AND BLACKS—BLACK GERMANS by Matthias Reiss MICHAEL SCHUBERT, Der schwarze Fremde: Das Bild des Schwarz- afrikaners in der parlamentarischen und publizistischen Kolonialdiskussion in Deutschland von den 1870er bis in die 1930er Jahren, Beitäge zur Ko- lonial- und Überseegeschichte, 86 (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2003), 446 pp. ISBN 3 515 08267 0. EUR 79.00 TINA M. CAMPT, Other Germans: Black Germans and the Politics of Race, Gender, and Memory in the Third Reich, Social History, Popular Culture, and Politics in Germany (Ann Arbor: University of Michig- an Press, 2004), x + 283 pp. ISBN 0 472 11360 7. $ 29.95 MARIANNE BECHHAUS-GERST and REINHARD KLEIN-ARENDT (eds.), AfrikanerInnen in Deutschland und schwarze Deutsche: Geschichte und Gegenwart, Encounters. History and Present of the African–Euro- pean Encounter/Begegnungen. Geschichte und Gegenwart der afri- kanisch-eruopäischen Begegnung, 3 (Münster: Lit Verlag, 2004), 261 pp. ISBN 3 8258 6824 9. EUR 20.90 In June 1972, the Allensbach Institut für Demoskopie conducted a poll on what the Germans thought about ‘the Negroes’ (die Neger). -

No Haven for the Oppressed

No Haven for the Oppressed NO HAVEN for the Oppressed United States Policy Toward Jewish Refugees, 1938-1945 by Saul S. Friedman YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY Wayne State University Press Detroit 1973 Copyright © 1973 by Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48202. All material in this work, except as identified below, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/. Excerpts from Arthur Miller’s Incident at Vichy formerly copyrighted © 1964 to Penguin Publishing Group now copyrighted to Penguin Random House. All material not licensed under a Creative Commons license is all rights reserved. Permission must be obtained from the copyright owner to use this material. Published simultaneously in Canada by the Copp Clark Publishing Company 517 Wellington Street, West Toronto 2B, Canada. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Friedman, Saul S 1937– No haven for the oppressed. Originally presented as the author’s thesis, Ohio State University. Includes bibliographical references. 1. Refugees, Jewish. 2. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945) 3. United States— Emigration and immigration. 4. Jews in the United States—Political and social conditions. I. Title. D810.J4F75 1973 940.53’159 72-2271 ISBN 978-0-8143-4373-9 (paperback); 978-0-8143-4374-6 (ebook) Publication of this book was assisted by the American Council of Learned Societies under a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The publication of this volume in a freely accessible digital format has been made possible by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Mellon Foundation through their Humanities Open Book Program. -

Fat Terrorist Bodies

AT ERRORIST ODIES F T B By Lorena D. Espinoza Guerrero Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Erasmus Mundus Master´s Degree in Women´s and Gender Studies (GEMMA) Main Supervisor: Dr. Nadia Jones-Gailani (Central European University) Second Supervisor: Dr. Adelina Sanchez Espinosa (University of Granada) Budapest, Hungary CEU eTD Collection 2020 FAT TERRORIST BODIES By Lorena D. Espinoza Guerrero Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Erasmus Mundus Master´s Degree in Women´s and Gender Studies (GEMMA) Main Supervisor: Dr. Nadia Jones-Gailani (Central European University) Second Supervisor: Dr. Adelina Sanchez Espinosa (University of Granada) Budapest, Hungary 2020 CEU eTD Collection DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is the result of original research; it contains no materials accepted for any other degree in any other institution and no materials previously written and/or published by another person, except where appropriate acknowledgment is made in the form of bibliographical reference. I further declare that the following word count for this thesis are accurate: Body of thesis (all chapters excluding notes, references, appendices, etc.): 32.527 words Entire manuscript: 49.065 words Signed Lorena D. Espinoza Guerrero CEU eTD Collection Abstract Fat, as a socially imposed adjective, contains a myriad of preconceptions and prejudices that have allowed engagements with fat bodies to be problematic at best, violent at worse. Fat bodies, through the construction of the obesity epidemic and the war against fat, have been transformed into dangerous bodies that generate and experience fear. -

Oceania in the Science of Race, 1750–1850

Chapter Two 'Novus Orbis Australis':1 Oceania in the science of race, 1750-1850 Bronwen Douglas In December 1828, the leading comparative anatomist Georges Cuvier (1769-1832) made a triumphalist presidential address (1829) to the annual general assembly of the Société de Géographie in Paris. He reminded his audience of the recent ©conquests of geography© which had revealed to the world the ©greatly varied tribes and countless islands© that the Ocean had thus far ©rendered unknown to the rest of humanity©. Cuvier©s ©conquests© were not merely topographical: ©our voyagers© in Oceania were ©philosophers and naturalists, no less than astronomers and surveyors©. They collected the ©products© of lands visited, studied the ©languages and customs© of the inhabitants, and enriched ©our museums, grammars and lexicons© as much as ©our atlases and maps©. ©Saved for science© in archives, natural history collections, and lavishly illustrated publications, this copious legacy of the classic era of scientific voyaging between 1766 and 1840 propelled Oceania to the empirical forefront of European knowledge Ð not least in the natural history of man and the nascent discipline of anthropology which made prime subject matter of the descriptions, portraits, plaster busts, human bodily remains, and artefacts repatriated by antipodean travellers and residents. History can be a potent antidote to the spurious aura of reality and permanence that infects reified concepts. This chapter and the previous one dislodge the realism of ©race© by historicizing it but do -

The Kpd and the Nsdap: a Sttjdy of the Relationship Between Political Extremes in Weimar Germany, 1923-1933 by Davis William

THE KPD AND THE NSDAP: A STTJDY OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN POLITICAL EXTREMES IN WEIMAR GERMANY, 1923-1933 BY DAVIS WILLIAM DAYCOCK A thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. The London School of Economics and Political Science, University of London 1980 1 ABSTRACT The German Communist Party's response to the rise of the Nazis was conditioned by its complicated political environment which included the influence of Soviet foreign policy requirements, the party's Marxist-Leninist outlook, its organizational structure and the democratic society of Weimar. Relying on the Communist press and theoretical journals, documentary collections drawn from several German archives, as well as interview material, and Nazi, Communist opposition and Social Democratic sources, this study traces the development of the KPD's tactical orientation towards the Nazis for the period 1923-1933. In so doing it complements the existing literature both by its extension of the chronological scope of enquiry and by its attention to the tactical requirements of the relationship as viewed from the perspective of the KPD. It concludes that for the whole of the period, KPD tactics were ambiguous and reflected the tensions between the various competing factors which shaped the party's policies. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE abbreviations 4 INTRODUCTION 7 CHAPTER I THE CONSTRAINTS ON CONFLICT 24 CHAPTER II 1923: THE FORMATIVE YEAR 67 CHAPTER III VARIATIONS ON THE SCHLAGETER THEME: THE CONTINUITIES IN COMMUNIST POLICY 1924-1928 124 CHAPTER IV COMMUNIST TACTICS AND THE NAZI ADVANCE, 1928-1932: THE RESPONSE TO NEW THREATS 166 CHAPTER V COMMUNIST TACTICS, 1928-1932: THE RESPONSE TO NEW OPPORTUNITIES 223 CHAPTER VI FLUCTUATIONS IN COMMUNIST TACTICS DURING 1932: DOUBTS IN THE ELEVENTH HOUR 273 CONCLUSIONS 307 APPENDIX I VOTING ALIGNMENTS IN THE REICHSTAG 1924-1932 333 APPENDIX II INTERVIEWS 335 BIBLIOGRAPHY 341 4 ABBREVIATIONS 1. -

Caucasian Race 1 Caucasian Race

Caucasian race 1 Caucasian race The term Caucasian race (also Caucasoid, Europid, or Europoid[1] ) has been used to denote the general physical type of some or all of the indigenous populations of Europe, North Africa, the Horn of Africa, West Asia, Central Asia, and South Asia.[2] Historically, the term has been used to describe the entire population of these regions, without regard necessarily to skin tone. In common use, specifically in American English, the term is sometimes restricted to Europeans and other lighter-skinned populations within these areas, and may be considered equivalent to the varying definitions of white people.[3] The 4th edition of Meyers Konversations-Lexikon (Leipzig, 1885-1890) shows the Caucasian race (in blue) as comprising Aryans, Semites and Hamites. Aryans are further subdivided into European Aryans and Indo-Aryans (the latter corresponding to the group now designated Indo-Iranians). Adjacent to the Caucasians are the Sudan-Negroes to the south (shown in brown), the Dravidians in India (shown in green) and Asians to the east (shown in yellow, subsuming the peoples now grouped under Uralic and Altaic (light yellow) and Sino-Tibetan (solid yellow)). Origin of the concept The concept of a Caucasian race or Varietas Caucasia was developed around 1800 by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, a German scientist and classical anthropologist.[4] Blumenbach named it after the peoples of the Caucasus (from the Caucasus region), whom he considered to be the archetype for the grouping.[5] He based his classification of the -

Racial Ideology Between Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany: Julius Evola and the Aryan Myth, 1933–43

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette History Faculty Research and Publications History, Department of 7-1-2020 Racial Ideology between Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany: Julius Evola and the Aryan Myth, 1933–43 Peter Staudenmaier Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/hist_fac Part of the History Commons Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette History Faculty Research and Publications/College of Arts and Sciences This paper is NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION. Access the published version via the link in the citation below. Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 55, No. 3 (July 1, 2020): 473-491. DOI. This article is © SAGE Publications and permission has been granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. SAGE Publications does not grant permission for this article to be further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without express permission from SAGE Publications. Racial Ideology between Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany: Julius Evola and the Aryan Myth, 1933–43 Peter Staudenmaier Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI Abstract One of the troublesome factors in the Rome–Berlin Axis before and during the Second World War centered on disagreements over racial ideology and corresponding antisemitic policies. A common image sees Fascist Italy as a reluctant partner on racial matters, largely dominated by its more powerful Nazi ally. This article offers a contrasting assessment, tracing the efforts by Italian theorist Julius Evola to cultivate a closer rapport between Italian and German variants of racism as part of a campaign by committed antisemites to strengthen the bonds uniting the fascist and Nazi cause. Evola's spiritual form of racism, based on a distinctive interpretation of the Aryan myth, generated considerable controversy among fascist and Nazi officials alike.