Audre Lorde: the Berlin Years 1984 to 1992: the Making of the Film and Its Reception

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Workonprogress Work in Progress On

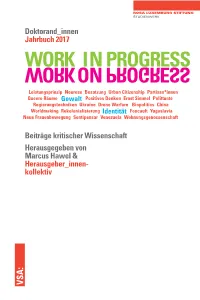

STUDIENWERK Doktorand_innen Jahrbuch 2017 ORK ON PROGRESS WORK INPROGRESS ON Leistungsprinzip Neurose Besatzung Urban Citizenship Partisan*innen Queere Räume Gewalt Positives Denken Ernst Simmel Polittunte Regierungstechniken Ukraine Drone Warfare Biopolitics China Worldmaking Rekolonialisierung Identität Foucault Yugoslavia Neue Frauenbewegung Sentipensar Venezuela Wohnungsgenossenschaft Beiträge kritischer Wissenschaft Herausgegeben von Marcus Hawel & Herausgeber_innen- kollektiv VSA: WORK IN PROGRESS. WORK ON PROGRESS Doktorand_innen-Jahrbuch 2017 der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung WORK IN PROGRESS. WORK ON PROGRESS. Beiträge kritischer Wissenschaft Doktorand_innenjahrbuch 2017 der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Herausgegeben von Marcus Hawel Herausgeber_innenkollektiv: Christine Braunersreuther, Philipp Frey, Sebastian Fritsch, Lucas Pohl und Julia Schwanke VSA: Verlag Hamburg www.vsa-verlag.de Inhalt www.rosalux.de/studienwerk Einleitung: Gewalt und Identität ......................................................... 9 Die Doktorand_innenjahrbücher 2012 (ISBN 978-3-89965-548-3), ZUSAMMENFASSUNGEN .................................................................. 23 2013 (ISBN 978-3-89965-583-4), 2014 (ISBN 978-3-89965-628-2), 2015 (ISBN 978-3-89965-684-8) und 2016 (ISBN 978-3-89965-738-8) der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung sind ebenfalls im VSA: Verlag ERKENNTNISTHEORIE UND METHODIK erschienen und können unter www.rosalux.de als pdf-Datei heruntergeladen werden. Kerstin Meißner Gefühlte Welt_en ............................................................................ -

German Studies Association Newsletter ______

______________________________________________________________________________ German Studies Association Newsletter __________________________________________________________________ Volume XLIV Number 1 Spring 2019 German Studies Association Newsletter Volume XLIV Number 1 Spring 2019 __________________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents Letter from the President ............................................................................................................... 2 Letter from the Executive Director ................................................................................................. 5 Conference Details .......................................................................................................................... 8 Conference Highlights ..................................................................................................................... 9 Election Results Announced ......................................................................................................... 14 A List of Dissertations in German Studies, 2017-19 ..................................................................... 16 Letter from the President Dear members and friends of the GSA, To many of us, “the GSA” refers principally to a conference that convenes annually in late September or early October in one city or another, and which provides opportunities to share ongoing work, to network with old and new friends and colleagues. And it is all of that, for sure: a forum for -

By Dagmar Schultz AUDRE LORDE – HER STRUGGLES and HER Visionsi in This Presentation I Will Try to Explain How Audre Lorde Came

By Dagmar Schultz AUDRE LORDE – HER STRUGGLES AND HER VISIONSi In this presentation I will try to explain how Audre Lorde came to Germany, what she meant to me personally and to Orlanda Women’s Publishers, and what effect her work had in Germany on Black and white women. In 1980, I met Audre Lorde for the first time at the UN World Women’s Conference in Copenhagen in a discussion following her reading. I knew nothing about her then, nor was I familiar with her books. I was spellbound and very much impressed with the openness with which Audre Lorde addressed us white women. She told us about the importance of her work as a poet, about racism and differences among women, about women in Europe, the USA and South Africa, and stressed the need for a vision of the future to guide our political praxis. On that evening it became clear to me: Audre Lorde must come to Germany for German women to hear her, her voice speaking to white women in an era when the movement had begun to show reactionary tendencies. She would help to pull it out of its provinciality, its over-reliance, in its politics, on the exclusive experience of white women. At that time I was teaching at the Free University of Berlin and thus had the opportunity to invite Audre Lorde to be a guest professor. In the spring of 1984 she agreed to come to Berlin for a semester to teach literature and creative writing. Earlier, in 1981, I had heard Audre Lorde and Jewish poet Adrienne Rich speaking about racism and antisemitism at the National Women’s Studies Association annual convention. -

First Century German Literature and Film

Abstract Title of Document: AMERICAN BLACKNESS AND VERGANGENHEITSBEWÄLTIGUNG IN TWENTY- FIRST CENTURY GERMAN LITERATURE AND FILM Christina Wall, Doctor of Philosophy, 2014 Directed by: Professor Elke P. Frederiksen, Department of Germanic Studies This study represents a unique examination of the convergence of constructs of Blackness and racism in twenty-first century novels and films by white Germans and Austrians in order to demonstrate how these texts broaden discourses of Vergangenheitsbewältigung. The increased prominence of minority voices demanding recognition of their national identity within Nazi successor states has transformed white German perceptions of “Germanness” and of these nations’ relationships to their turbulent pasts. I analyze how authors and directors employ constructs of Blackness within fictional texts to interrogate the dynamics of historical and contemporary racisms. Acknowledging that discourses of ‘race’ are taboo, I analyze how authors and directors avoid this forbidden discourse by drawing comparisons between constructs of American Blackness and German and Austrian historical encounters with ‘race’. This study employs cultural studies’ understanding of ‘race’ and Blackness as constructs created across discourses. Following the example of Toni Morrison’s Playing in the Dark (1992), my textual analyses show how these constructs create a “playground for the imagination” in which authors confront modern German racism. My study begins with a brief history of German-African American encounters, emphasizing the role American Blackness played during pivotal moments of German national identity formation. The subsequent chapters are divided thematically, each one comprised of textual analyses that explore discourses integral to Vergangenheitsbewältigung. The third chapter examines articulations of violence and racism in two films, Oskar Roehler’s Lulu & Jimi (2008) and Michael Schorr’s Schultze gets the blues (2008), to explore possibilities of familial reconciliation despite historical guilt. -

Khwaja Abdul Hamied

On the Margins <UN> Muslim Minorities Editorial Board Jørgen S. Nielsen (University of Copenhagen) Aminah McCloud (DePaul University, Chicago) Jörn Thielmann (Erlangen University) volume 34 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/mumi <UN> On the Margins Jews and Muslims in Interwar Berlin By Gerdien Jonker leiden | boston <UN> This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Cover illustration: The hiking club in Grunewald, 1934. PA Oettinger, courtesy Suhail Ahmad. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Jonker, Gerdien, author. Title: On the margins : Jews and Muslims in interwar Berlin / by Gerdien Jonker. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, [2020] | Series: Muslim minorities, 1570–7571 ; volume 34 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019051623 (print) | LCCN 2019051624 (ebook) | ISBN 9789004418738 (hardback) | ISBN 9789004421813 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Jews--Germany--Berlin--Social conditions--20th century. | Muslims--Germany--Berlin--Social conditions--20th century. | Muslims --Cultural assimilation--Germany--Berlin. | Jews --Cultural assimilation --Germany--Berlin. | Judaism--Relations--Islam. | Islam --Relations--Judaism. | Social integration--Germany--Berlin. -

Prelims May 2005.Qxd

German Historical Institute London Bulletin Bd. 27 2005 Nr. 1 Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Stiftung Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hinausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weitergabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich verfolgt werden. REVIEW ARTICLES GERMANS AND BLACKS—BLACK GERMANS by Matthias Reiss MICHAEL SCHUBERT, Der schwarze Fremde: Das Bild des Schwarz- afrikaners in der parlamentarischen und publizistischen Kolonialdiskussion in Deutschland von den 1870er bis in die 1930er Jahren, Beitäge zur Ko- lonial- und Überseegeschichte, 86 (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2003), 446 pp. ISBN 3 515 08267 0. EUR 79.00 TINA M. CAMPT, Other Germans: Black Germans and the Politics of Race, Gender, and Memory in the Third Reich, Social History, Popular Culture, and Politics in Germany (Ann Arbor: University of Michig- an Press, 2004), x + 283 pp. ISBN 0 472 11360 7. $ 29.95 MARIANNE BECHHAUS-GERST and REINHARD KLEIN-ARENDT (eds.), AfrikanerInnen in Deutschland und schwarze Deutsche: Geschichte und Gegenwart, Encounters. History and Present of the African–Euro- pean Encounter/Begegnungen. Geschichte und Gegenwart der afri- kanisch-eruopäischen Begegnung, 3 (Münster: Lit Verlag, 2004), 261 pp. ISBN 3 8258 6824 9. EUR 20.90 In June 1972, the Allensbach Institut für Demoskopie conducted a poll on what the Germans thought about ‘the Negroes’ (die Neger). -

Heimattransgressions, Transgressing Heimat

Vanessa D. Plumly Heimat Transgressions, Transgressing Heimat Black German Diasporic (Per)Formative Acts in the Decolonization of White German Heimat Landscapes Black/Afro-Germans1 embody the fear of sexual transgressions and miscegeny that racist discourse in the former German colonies instilled in white Germans and that Wilhelminian Germany legally sanctioned through the ius sangui- nus definition of German citizenship.2 The Third Reich further exploited this through its enactment of the Nuremberg laws, which once again considered Black Germans non-members of the imagined national German community. Today, Black Germans remain excluded from the reunited Berlin Republic, even though a new citizenship law passed in the Federal Republic in 1999 signaled a transition away from Germany’s blood-based definition toward a more civic one, and despite the fact that some Black Germans can trace their German ancestry over three or more generations.3 White Germans’ constant questioning of Black Germans’ origins because of their racial constitution and visible diasporic roots performatively enacts this resolute denial of their na- tional identity and belonging.4 1 The word Afro-German is used most often to denote Black Germans with one white German parent and one black or African/African diasporic parent, and Black German is most often used to denote anyone who chooses to identify with the term and has had similar experi- ences of racial exclusions. See Katharina Oguntoye, May Ayim (Opitz), and Dagmar Schultz, Farbe bekennen: Afro-deutsche Frauen auf den Spuren ihrer Geschichte, Frankfurt a.M. 1992, p. 10. 2 El-Tayeb makes clear that »›German blood‹ meant explicitly ›white blood‹«, in Fatima El- Tayeb, »We are Germans, We are Whites, and We Want to Stay White!« Amsterdamer Beiträge zur neueren Germanistik (2004), 56.1, pp. -

Fat Terrorist Bodies

AT ERRORIST ODIES F T B By Lorena D. Espinoza Guerrero Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Erasmus Mundus Master´s Degree in Women´s and Gender Studies (GEMMA) Main Supervisor: Dr. Nadia Jones-Gailani (Central European University) Second Supervisor: Dr. Adelina Sanchez Espinosa (University of Granada) Budapest, Hungary CEU eTD Collection 2020 FAT TERRORIST BODIES By Lorena D. Espinoza Guerrero Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Erasmus Mundus Master´s Degree in Women´s and Gender Studies (GEMMA) Main Supervisor: Dr. Nadia Jones-Gailani (Central European University) Second Supervisor: Dr. Adelina Sanchez Espinosa (University of Granada) Budapest, Hungary 2020 CEU eTD Collection DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is the result of original research; it contains no materials accepted for any other degree in any other institution and no materials previously written and/or published by another person, except where appropriate acknowledgment is made in the form of bibliographical reference. I further declare that the following word count for this thesis are accurate: Body of thesis (all chapters excluding notes, references, appendices, etc.): 32.527 words Entire manuscript: 49.065 words Signed Lorena D. Espinoza Guerrero CEU eTD Collection Abstract Fat, as a socially imposed adjective, contains a myriad of preconceptions and prejudices that have allowed engagements with fat bodies to be problematic at best, violent at worse. Fat bodies, through the construction of the obesity epidemic and the war against fat, have been transformed into dangerous bodies that generate and experience fear. -

May Ayim E a Tradução Da Poesia Afrodiaspórica De Língua Alemã

Jessica Flavia Oliveira de Jesus MAY AYIM E A TRADUÇÃO DE POESIA AFRODIASPÓRICA DE LÍNGUA ALEMÃ Dissertação submetida ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Estudos da Tradução da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina para a obtenção do Grau de mestra em Estudos da Tradução. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Rosvitha Friesen Blume Florianópolis 2018 Ficha de identificação da obra elaborada pela autora através do Programa de Geração Automática da Biblioteca Universitária da UFSC. Oliveira de Jesus, Jessica Flavia May Ayim e a Tradução de Poesia Afrodiaspórica de Língua Alemã / Jessica Flavia Oliveira de Jesus; orientadora, Rosvitha Friesen Blume, 2018. 165 p. Dissertação (mestrado) - Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Centro de Comunicação e Expressão, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Estudos da Tradução, Florianópolis, 2018. Inclui referências. 1. Estudos da Tradução. 2. Tradução. 3. Poesia Negra. 4. Poesia Alemã. 5. May Ayim. I. Blume, Rosvitha Friesen. II. Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Estudos da Tradução. III. Título. In memoriam a May Ayim, Marcella Maria, a MC Xuparina e Marielle Franco AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço a Oyá, dona dos ventos que me guiam pelas diásporas, seja onde for, me proporcionando encontros, olhares, sorrisos, abraços, cumplicidades, trocas intelectuais/amorosas Negras preciosas e por ter me soprado: vaaaaai. Agradeço a Yemanjá, rainha do mar que me acompanhou e embalou durante os dois anos de elaboração e escrita desta dissertação em Florianópolis, onde estive cercada por sua energia, sentindo sua presença em cada brisa do mar. A minha mãe, Nadir Oliveira por sempre me apoiar. E ao pa(i)drasto Nelson Silva Costa, por ser quem ele é. -

AUDRE LORDE: Dream of Europe 90000> SELECTED SEMINARS and INTERVIEWS 1984–1992

ISBN 978-0-9997198-7-9 AUDRE LORDE: dream of europe 90000> SELECTED SEMINARS AND INTERVIEWS 1984–1992 9780999 719879 AUDRE LORDE AUDRE : dream of europe dream of AUDRE LORDE: dream of europe elucidates Lorde’s methodology as a poet, mentor, and activist during the last decade of her life. This volume compiles a series of seminars, interviews, and conversations held by the author and collaborators across Berlin, Western Europe, and The Caribbean between 1984-1992. While Lorde stood at the intersection of various historical and literary movements in The United States—the uprising of black social life after the Harlem Renaissance, poetry of the AIDS epidemic, and the unfolding of the Civil Rights Movement-- this selection of texts reveals Lorde as a catalyst for the first movement of Black Germans in West Berlin. Lorde’s intermittent residence in Berlin lasted for nearly ten years, a period where she inspired many important local and global initiatives, from individual poets to international movements. The legacy of this “Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet” has been well persevered by her colleagues in Germany. It is an erotics of friendship that allowed Lorde and her collaborators EDITIONSKENNING to develop a strong sense of political responsibility for each other, transforming alliance and love Edited, with an afterword between women into tools for social change. These selected writings lay bare struggles, bonds, and by Mayra A. Rodríguez Castro Preface by Dagmar Schultz hopes shared among Black women in a transnational political context. POETRY | POLITICS KENNING EDITIONS POETRY | POLITICS KENNING EDITIONS AUDRE LORDE Lorde_Dream-draft.indd 2-3 11/14/19 8:39 AM DREAM OF EUROPE SELECTED SEMINARS AND INTERVIEWS: 1984-1992 Edited, with an afterword, by Mayra A. -

German-Speaking Women, Africa, and the African Diaspora (01.10.2018)

H-Germanistik CFP: Afrika and Alemania: German-Speaking Women, Africa, and the African Diaspora (01.10.2018) Discussion published by Lisabeth Hock on Thursday, July 26, 2018 Call for Abstracts Afrika and Alemania: German-Speaking Women, Africa, and the African Diaspora Respond to Coeditors: Lisabeth Hock ([email protected]) Michelle James ([email protected]) Priscilla Layne ([email protected]) 250-Word Abstracts Due: October 1, 2018 While connections between Germanic Europeans and African-descended peoples can be traced back to the Middle Ages, the first known text to engage with Africa by a German-speaking woman was produced at the end of the eighteenth century. In the centuries to follow, most women with the education and authority to produce accounts of Africa identified as—or had the privilege of not having to identify as—white. In twentieth and twenty-first centuries, however, an increasing number of German-speaking women have identified as Black or Brown and have written about Africa and the African diaspora from a Black German perspective. With the aim of exploring the ways in which white German-speaking women and German-speaking Women of Color have represented Africa, Lisabeth Hock, Michelle James and Pricilla Layne announce a call for papers for a volume on German-Speaking Women, Africa, and the African Diaspora. This will be a companion to the 2014 Camden House volume, Sophie Discovers Amerika: German-Speaking Women Write the New World, coedited by Michelle James and Rob McFarland The history of Afrika and Alemania begins in 1799, when Jewish writer and salon hostess Henrietta Herz (1764-1847) translated into German the Scottish explorer Mungo Park’s Journey to the Interior of Africa in the Years 1795 and 1797. -

May Ayim's Legacy in World Language Study

FLANC Newsletter, Spring 2012: May Ayim’s Legacy in World Language Study May Ayim’s Legacy in World Language Study At last year’s Foreign Language Association of Northern California Conference (FLANC 2011) I had the pleasure to present a double session on May Ayim (1960-1996), an extraordinary Ghanaian-German poet, scholar, activist, and speech therapist. Although Ayim was a prolific writer, she has remained relatively unknown to many Germans and teachers of German. However, her work should not be confined to German studies and deserves to be brought to a global public. I believe students of other world languages will benefit greatly from Ayim’s writing. She integrated poetry with cultural diversity and anti-racism work, which stimulates students’ engagement at middle, high school and college levels. Some of Ayim’s poems have been translated into English and Hindi but why stop there? Based on the presentation at our FLANC sessions, I’d like to introduce May Ayim and her critical contributions to German language, literature, and culture. I’ll provide examples of (the breadth of) her poetry in both German and English and give some suggestions for how to use her work in teaching. Ayim’s Diplomarbeit (thesis) “Afro-Deutsche. Ihre Kultur- und Sozialgeschichte auf dem Hintergrund gesellschaftlicher Veränderungen” (“Afro-Germans: Their Cultural and Social History on The Background of Societal Change”) in 1986 was the first scholarly work on Afro-German history spanning the Middle Ages to the present. Her thesis provided the foundation of the book Farbe bekennen, published one year later. Farbe bekennen was fundamental to the Black German movement and has inspired work in Germany and beyond its borders.