Downloaded August 21, 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book-91249.Pdf

THE MILITARY IN NIGERIAN POLITICS (1966-1979): CORRECTIVE AGENT OR MERE USURPER OF POWER? By SHINA L. F. AMACHIGH " Bachelor of Arts Ahmadu Bello University Samaru-Zaria, Nigeria 1979 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate Col lege of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1986 THE MILITARY IN NIGERIAN POLITICS (1966-1979): CORRECTIVE AGENT OR MERE USURPER OF POWER? Thesis Approved: Dean of the Graduate College 1251198 i i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My foremost thanks go to my heavenly Father, the Lord Jesus Christ and the Holy Spirit for the completion of this study. Thank you, Dr. Lawler (committee chair), for your guidance and as sistance and for letting me use a dozen or so of your personal textbooks throughout the duration of this study. Appreciation is also expressed to the other committee members, Drs. von Sauer and Sare, for their in valuable assistance in preparation of the final manuscript. Thank you, Ruby and Amen (my wife and son) for not fussing all the times I had to be 11 gone again. 11 I love you. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I • INTRODUCTION Backqround 1 The Problem 2 Thesis and Purpose 2 Analytical Framework and Methodology 3 I I. REVIEW OF THEORETICAL LITERATURE 5 The Ataturk Model ....• 16 The Origins of Military Intervention 18 Africa South of the Sahara .... 20 I II. BRIEF HISTORY OF MILITARY INVOLVEMENT IN NIGERIAN POLITICS (1966-1979) 23 IV. THE PROBLEM OF NATIONAL INTEGRATION 29 British Colonialism and National Inte- gration in Nigeria .... -

Unclaimed-Dividend202047.Pdf

UNCLAIMED DIVIDENDS 1 (HRH OBA) GABRIEL OLATERU ADEWOYE 140 ABDULLAHI AHMED 279 ABIGAL ODUNAYO LUCAS 418 ABOSEDE ADETUTU ORESANYA 2 (NZE) SUNDAY PAUL EZIEFULA 141 ABDULLAHI ALIU ADAMU 280 ABIGALIE OKUNWA OKAFOR 419 ABOSEDE AFOLAKEMI IBIDAPO-OBE 3 A A J ENIOLA 142 ABDULLAHI AYINLA ABDULRAZAQ 281 ABIJO AYODEJI ADEKUNLE 420 ABOSEDE BENEDICTA ONAKOYA 4 A A OYEGBADE 143 ABDULLAHI BILAL FATSUMA 282 ABIJOH BALIKIS ADESOLA 421 ABOSEDE DUPE ODUMADE 5 A A SIJUADE 144 ABDULLAHI BUKAR 283 ABIKE OTUSANYA 422 ABOSEDE JEMILA IBRAHIM 6 A BASHIR IRON BABA 145 ABDULLAHI DAN ASABE MOHAMMED 284 ABIKELE GRACE 423 ABOSEDE OLAYEMI OJO 7 A. ADESIHMA FAJEMILEHIN 146 ABDULLAHI DIKKO KASSIM (ALH) 285 ABIMBADE ATANDA WOJUADE 424 ABOSEDE OLUBUNMI SALAU (MISS) 8 A. AKINOLA 147 ABDULLAHI ELEWUETU YAHAYA (ALHAJI) 286 ABIMBOLA ABENI BAMGBOYE 425 ABOSEDE OMOLARA AWONIYI (MRS) 9 A. OLADELE JACOB 148 ABDULLAHI GUNDA INUSA 287 ABIMBOLA ABOSEDE OGUNNIEKAN 426 ABOSEDE OMOTUNDE ABOABA 10 A. OYEFUNSO OYEWUNMI 149 ABDULLAHI HALITA MAIBASIRA 288 ABIMBOLA ALICE ALADE 427 ABOSI LIVINUS OGBUJI 11 A. RAHMAN BUSARI 150 ABDULLAHI HARUNA 289 ABIMBOLA AMUDALAT BALOGUN 428 ABRADAN INVESTMENTS LIMITED 12 A.A. UGOJI 151 ABDULLAHI IBRAHIM RAIYAHI 290 ABIMBOLA AREMU 429 ABRAHAM A OLADEHINDE 13 AAA STOCKBROKERS LTD 152 ABDULLAHI KAMATU 291 ABIMBOLA AUGUSTA 430 ABRAHAM ABAYOMI AJAYI 14 AARON CHIGOZIE IDIKA 153 ABDULLAHI KURAYE 292 ABIMBOLA EKUNDAYO ODUNSI (MISS) 431 ABRAHAM ABU OSHIAFI 15 AARON IBEGBUNA AKABIKE 154 ABDULLAHI MACHIKA OTHMAN 293 ABIMBOLA FALI SANUSI-LAWAL 432 ABRAHAM AJEWOLE ARE 16 AARON M AMAK DAMAK 155 ABDULLAHI MAILAFIYA ABUBAKAR 294 ABIMBOLA FAUSAT ADELEKAN 433 ABRAHAM AJIBOYE OJEDELE 17 AARON OBIAKOR 156 ABDULLAHI MOHAMMED 295 ABIMBOLA FEHINTOLA 434 ABRAHAM AKEJU OMOLE 18 AARON OLUFEMI 157 ABDULLAHI MOHAMMED ABDULLAHI 296 ABIMBOLA KEHINDE OLUWATOYIN 435 ABRAHAM AKINDELE TALABI 19 AARON U. -

Boko Haram, Resulting in a Narrative of a Unified Muslim Programme for Conquest, Domination and Forced Conversion

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Ethics and World-view in Identity-based Conflict in Nigeria A Practical Theological Perspective on The Religious Dimension of Violence in Plateau State Bruce Kirkwood Campbell PhD Practical Theology The University of Edinburgh January 2015 Abstract Severe intercommunal violence has repeatedly rocked Plateau State in the first decade of the new millennium, killing thousands of people. Observers have attributed the ªcrisisº to political, economic and social forces which breed pockets of exclusion and resentment. One notable model explains the violence through a paradigm of privileged ªindigenesº who seek to prevent ªsettlersº from the political rights which would give them the access to the resources managed by the state and the economic opportunities that this entails. While not taking issue with the diagnosed causes of conflict, the Researcher argues that there is a substantial body of evidence being ignored which points to conflict cleavage having opened up along the divide of Christian-Muslim religious identity in a way that the settler-identity model does not sufficiently explain. -

Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University In

79I /f NIGERIAN MILITARY GOVERNMENT AND PRESS FREEDOM, 1966-79 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Ehikioya Agboaye, B.A. Denton, Texas May, 1984 Agboaye, Ehikioya, Nigerian Military Government and Press Freedom, 1966-79. Master of Arts (Journalism), May, 1984, 3 tables, 111 pp., bibliography, 148 titles. The problem of this thesis is to examine the military- press relationship inNigeria from 1966 to 1979 and to determine whether activities of the military government contributed to violation of press freedom by prior restraint, postpublication censorship and penalization. Newspaper and magazine articles related to this study were analyzed. Interviews with some journalists and mili- tary personnel were also conducted. Materials collected show that the military violated some aspects of press freedom, but in most cases, however, journalists were free to criticize government activities. The judiciary prevented the military from arbitrarily using its power against the press. The findings show that although the military occasionally attempted suppressing the press, there are few instances that prove that journalists were denied press freedom. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES............ .P Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . 1 Statement of the Problem Purpose of the Study Significant Questions Definition of Terms Review of the Literature Significance of the Study Limitations Methodology Organization II. PREMILITARY ERA,.... 1865-1966...18 . From Colonial to Indigenous Press The Press in the First Republic III. PRESS ACTIONS IN THE MILITARY'S EARLY YEARS 29 Before the Civil War The Nigeria-Biaf ran War and After IV. -

SENATE of the FEDERAL REPUBLIC of NIGERIA VOTES and PROCEEDINGS Tuesday, 9Th June, 2015

8TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY FIRST SESSION No.1 1 SENATE OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS Tuesday, 9th June, 2015 1. The Senate met at 10: 00 a.m. pursuant to the proclamation by the President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, Muhammadu Bubari. //·····\;·n~l'. 1r) I" .,"-~~:~;;u~~;~)'::.Y1 PRESIDENT, FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA Your Excellency, PROCLAMATION FOR THE HOLDING OF THE FIRST SESSION OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY WHEREASit is provided in Section 64(3) of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (As Amended) that the person Elected as President shall have power to issue a proclamation for the holding of the First Session of the National Assembly immediately after his being sworn-in. NOW,mEREFORE,I Muhammadu Buhari, President, Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, in exercise of thepowers bestowed upon me by Section (64) aforesaid, and of all other powers enabling me in that behalf hereby proclaim that the First Session of the eight (8h) National Assembly shall hold at 10.00 a.m. on Tuesday, 9th June, 2015 in the National Assembly, Abuja. Given under my hand and the Public Seal of the Federal Republic of Nigeria at Abuja, this P Day of June, 2015. Yours Sincerely, (Signed) Muhammadu Buhari President, Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces Federal Republic of Nigeria 2. At 10.04 a.m. the Clerk to the National Assembly called the Senate to order and informed Senators-Elect that writs had been received in respect of the elections held on 28th March, 2015 in accordance with the Constitution. -

Accredited Observer Groups/Organisations for the 2011 April General Elections

ACCREDITED OBSERVER GROUPS/ORGANISATIONS FOR THE 2011 APRIL GENERAL ELECTIONS Further to the submission of application by Observer groups to INEC (EMOC 01 Forms) for Election Observation ahead of the April 2011 General Elections; the Commission has shortlisted and approved 291 Domestic Observer Groups/Organizations to observe the forthcoming General Elections. All successful accredited Observer groups as shortlisted below are required to fill EMOC 02 Forms and submit the full names of their officials and the State of deployment to the Election Monitoring and Observation Unit, INEC. Please note that EMOC 02 Form is obtainable at INEC Headquarters, Abuja and your submissions should be made on or before Friday, 25th March, 2011. S/N ORGANISATION LOCATION & ADDRESS 1 CENTER FOR PEACEBUILDING $ SOCIO- HERITAGE HOUSE ILUGA QUARTERS HOSPITAL ECONOMIC RESOURCES ROAD TEMIDIRE IKOLE EKITI DEVELOPMENT(CEPSERD) 2 COMMITTED ADVOCATES FOR SUSTAINABLE DEV SUITE 18 DANOVILLE PLAZA GARDEN ABUJA &YOUTH ADVANCEMENT FCT 3 LEAGUE OF ANAMBRA PROFESSIONALS 86A ISALE-EKO WAY DOLPHIN – IKOYI 4 YOUTH MOVEMENT OF NIGERIA SUITE 24, BLK A CYPRIAN EKWENSI CENTRE FOR ARTS & CULTURE ABUJA 5 SCIENCE & ECONOMY DEV. ORG. SUITE KO5 METRO PLAZA PLOT 791/992 ZAKARIYA ST CBD ABUJA 6 GLOBAL PEACE & FORGIVENESS FOUNDATION SUITE A6, BOBSAR COMPLEX GARKI 7 CENTRE FOR ACADEMIC ENRICHMENT 2 CASABLANCA ST. WUSE 11 ABUJA 8 GREATER TOMORROW INITIATIVE 5 NSIT ST, UYO A/IBOM 9 NIG. LABOUR CONGRESS LABOUR HOUSE CBD ABUJA 10 WOMEN FOR PEACE IN NIG NO. 4 MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY KADUNA 11 YOUTH FOR AGRICULTURE 15 OKEAGBE CLOSE ABUJA 12 COALITION OF DEMOCRATS FOR ELECTORAL 6 DJIBOUTI CRESCENT WUSE 11, ABUJA REFORMS 13 UNIVERSAL DEFENDERS OF DEMOCRACY UKWE HOUSE, PLOT 226 CENSUS CLOSE, BABS ANIMASHANUN ST. -

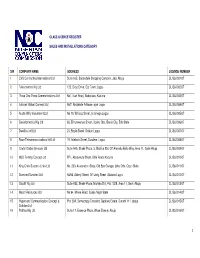

S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07

CLASS LICENCE REGISTER SALES AND INSTALLATIONS CATEGORY S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07 2 Telesciences Nig Ltd 123, Olojo Drive, Ojo Town, Lagos CL/S&I/002/07 3 Three One Three Communications Ltd No1, Isah Road, Badarawa, Kaduna CL/S&I/003/07 4 Latshak Global Concept Ltd No7, Abolakale Arikawe, ajah Lagos CL/S&I/004/07 5 Austin Willy Investment Ltd No 10, Willisco Street, Iju Ishaga Lagos CL/S&I/005/07 6 Geoinformatics Nig Ltd 65, Erhumwunse Street, Uzebu Qtrs, Benin City, Edo State CL/S&I/006/07 7 Dwellins Intl Ltd 21, Boyle Street, Onikan Lagos CL/S&I/007/07 8 Race Telecommunications Intl Ltd 19, Adebola Street, Surulere, Lagos CL/S&I/008/07 9 Clarfel Global Services Ltd Suite A45, Shakir Plaza, 3, Michika Strt, Off Ahmadu Bello Way, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/009/07 10 MLD Temmy Concept Ltd FF1, Abeoukuta Street, Bida Road, Kaduna CL/S&I/010/07 11 King Chris Success Links Ltd No, 230, Association Shop, Old Epe Garage, Ijebu Ode, Ogun State CL/S&I/011/07 12 Diamond Sundries Ltd 54/56, Adeniji Street, Off Unity Street, Alakuko Lagos CL/S&I/012/07 13 Olucliff Nig Ltd Suite A33, Shakir Plaza, Michika Strt, Plot 1029, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/013/07 14 Mecof Resources Ltd No 94, Minna Road, Suleja Niger State CL/S&I/014/07 15 Hypersand Communication Concept & Plot 29A, Democracy Crescent, Gaduwa Estate, Durumi 111, abuja CL/S&I/015/07 Solution Ltd 16 Patittas Nig Ltd Suite 17, Essence Plaza, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja CL/S&I/016/07 1 17 T.J. -

An Assessment of Civil Military Relations in Nigeria As an Emerging Democracy, 1999-2007

AN ASSESSMENT OF CIVIL MILITARY RELATIONS IN NIGERIA AS AN EMERGING DEMOCRACY, 1999-2007 BY MOHAMMED LAWAL TAFIDA DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA NIGERIA JUNE 2015 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis entitled An Assessment of Civil-Military Relations in Nigeria as an Emerging Democracy, 1999-2007 has been carried out and written by me under the supervision of Dr. Hudu Ayuba Abdullahi, Dr. Mohamed Faal and Professor Paul Pindar Izah in the Department of Political Science and International Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria. The information derived from the literature has been duly acknowledged in the text and a list of references provided in the work. No part of this dissertation has been previously presented for another degree programme in any university. Mohammed Lawal TAFIDA ____________________ _____________________ Signature Date CERTIFICATION PAGE This thesis entitled: AN ASSESSMENT OF CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS IN NIGERIA AS AN EMERGING DEMOCRACY, 1999-2007 meets the regulations governing the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science of the Ahmadu Bello University Zaria and is approved for its contribution to knowledge and literary presentation. Dr. Hudu Ayuba Abdullahi ___________________ ________________ Chairman, Supervisory Committee Signature Date Dr. Mohamed Faal________ ___________________ _______________ Member, Supervisory Committee Signature Date Professor Paul Pindar Izah ___________________ -

UNIMAID UTME Admission List

UNIVERSITY OF MAIDUGURI (Office of the Registrar) FIRST BATCH UTME ADMISSION 2019/2020 SESSION COLLEGE OF MEDICAL SCIENCES FACULTY OF CLINICAL SCIENCES/FACULTY OF BASIC CLINICAL SCIENCES S/No JAMB No NAME COURSE 1 97083561GC Musbaudeen Soliudeen Adesina MBBS 2 95412542GC Ayuba Jesse Dabawa MBBS 3 97290769BE Idris Kaab MBBS 4 95441515FF Ishaku Adams Ali MBBS 5 95290922AI Muhammad Musa Katuzu MBBS 6 95395022EI Edache Las Edache MBBS 7 95094446GE Dauda Abdulrazak MBBS 8 97291019EA Hudu Sagir MBBS 9 96314314HG Ahovi Abdulazeez Amadu MBBS 10 95429712FJ Obaje Prince Adakole MBBS 11 95422025DE Asindaya Philip Gadzama MBBS 12 95872179AG Musa Yahya MBBS 13 96668055DD Adebayo David Adeoluwa MBBS 14 95413556CH Modu Muhammad Kafa MBBS 15 96363868BI Abdulbaqi Maryam MBBS 16 95417387HH Habila Ikpesiudeng MBBS 17 96297196CA Usman Emmanuel MBBS 18 96924444HG Adetokun James Adetayo MBBS 19 95416033GF Dickson Jemimah Chinaza MBBS 20 97080261GI Owonikoko Toyeeb Olubodun MBBS 21 97431352CB Teryila Hilary Aondona MBBS 22 95288423DG Isa Abdussalam Muhammad MBBS 23 95420838AG Mohammed Sadiyat Halima MBBS 24 95195502CB Ekwenugo Paul Onyedikachukwu MBBS 25 95429264EF Bello Muhammad MBBS 26 96039231EJ Akinwumi Rilwan MBBS 27 95286925GI Muhammad Musa Ahmed MBBS 28 96152978FE Muhammad Abubakar Tanga MBBS 29 95435568EI Ojo Oluwatobiloba MBBS 30 95290673HG Chutiyami Abdulwahab MBBS 31 97295973BJ Bello Babayo MBBS 32 95439076JH Anthony Adacha Garari MBBS 33 95648876DD Abdulkareem Haneef Ademola MBBS 34 95419015ED Favour Nuhu MBBS 35 95429003FC Ibrahim Jeremiah Maiva -

The Venus Medicare Hospital Directory

NATIONWIDE PROVIDER DIRECTORY CATEGORY 1 HOSPITALS S/N STATE CITY/TOWN/DISTRICT HEALTHCARE PROVIDER ADDRESS TERMS & CONDITIONS SERVICES Primary, O&G, General Surgery, Paediatrics, 1 FCT/ABUJA CENTRAL AREA Limi Hospital & Maternity Plot 541Central District, Behind NDIC/ICPC HQ, Abuja Nil Internal Medicine Primary, Int. Med, Paediatrics,O&G, GARKI Garki Hospital Abuja Tafawa Balewa Way, Area 3, Garki, Abuja Private Wards not available. Surgery,Dermatology Amana Medical Centre 5 Ilorin str, off ogbomosho str,Area 8, Garki Nil No.5 Plot 802 Malumfashi Close, Off Emeka Anyaoku Strt, Alliance Clinics and Services Area 11 Nil Primary, Int. Med, Paediatrics Primary, O&G, General Surgery, Paediatrics, Internal Medicine Dara Medical Clinics Plot 202 Bacita Close, off Plateau Street, Area 2 Nil Primary, O&G, General Surgery, Paediatrics, Internal Medicine Sybron Medical Centre 25, Mungo Park Close, Area 11, Garki, Abuja Nil Primary, O&G, Paediatrics,Int Medicine, Gen Guinea Savannah Medical Centre Communal Centre, NNPC Housing Estate, Area II, Garki Nil Surgery, Laboratory Bio-Royal Hospital Ltd 11, Jebba Close, Off Ogun Street, Area 2, Garki Nil Primary, Surgery, Paediatrics. Primary, Family Med, O & G, Gen Surgery, Royal Specialist Hospital 2 Kukawa Street, Off Gimbiyan Street Area 11, Garki, Abuja Nil Urology, ENT, Radiology, Paediatrics No.4 Ikot Ekpene Close, Off Emeka Anyaoku Street Crystal Clinics (opposite National Assembly Clinic) Garki Area 11 Nil Primary, O&G, Paediatrics, Internal Medicine, Surgery Model Care Hospital & Consultancy Primary, Paediatrics, Surgery and ENT Limited No 5 Jaba Close, off Dunukofia Street by FCDA Garki, Abuja Nil Surgery Primary, O&G, General Surgery, Paediatrics, GARKI II Fereprod Medical Centre Obbo Crescent, off Ahmadu Bello Way, Garki II Nil Internal Medicine Holy Trinity Hospital 22 Oroago Str, by Ferma/Old CBN HQ, Garki II Nil Primary only. -

Shippers Registration Form

FORM No: NSC/SRS/97/0030/II NIGERIAN SHIPPERS’ COUNCIL (Established by CAP 327 of Laws of the Federation of Nigeria) MEMBERSHIP APPLICATION FORM Please return after completion to: TYPE OF MEMBERSHIP REQUIRED (Tick One) The Registrar, CORPORATE (Limited Liability Companies, PLCs etc.) Shippers' Registration Scheme, Nigerian Shippers’ Council, TRADE GROUP / ASSOCIATION (commodity groups, 4, Park Lane, Apapa, chambers of commerce, recognised business groups) P. M. B. 50617, Ikoyi, Lagos. BUSINESS NAMES (own name, partnerships, business Tel: 01 – 5458813-14 names) E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.shipperscouncil.com PUBLIC AGENCY (Federal/State/Local Government organisations, parastatals and companies etc. ) OR: Any Nigerian Shippers’ Council office nearest to you. ASSOCIATE (potential shippers, clearing & forwarding (Please see reverse side for addresses) companies, insurance companies, banks, law firms etc.) APPLICANT SHIPPER’S DATA NAME_________________________________________________________________________________________ (Name of Company / Group /Business Names / Agency / Associate to be registered) ADDRESS_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ (Street Name) CITY_____________________ STATE_____________________P. O. BOX___________________P. M. B__________________________ TELEPHONE________________________ FAX_________________________E-MAIL_________________________________ CONTACT PERSON___________________________________________DESIGNATION___________________________________________ -

Click Here to Download

AHISTORYOFNIGERIA Nigeria is Africa’s most populous country and the world’s eighth largest oil producer, but its success has been undermined in recent decades by ethnic and religious conflict, political instability, rampant official corruption, and an ailing economy. Toyin Falola, a leading historian intimately acquainted with the region, and Matthew Heaton, who has worked extensively on African science and culture, combine their expertise to explain the context to Nigeria’s recent troubles, through an exploration of its pre-colonial and colonial past and its journey from independence to statehood. By exami- ning key themes such as colonialism, religion, slavery, nationalism, and the economy, the authors show how Nigeria’s history has been swayed by the vicissitudes of the world around it, and how Nigerians have adapted to meet these challenges. This book offers a unique portrayal of a resilient people living in a country with immense, but unrealized, potential. toyin falola is the Frances Higginbotham Nalle Centennial Professor in History at the University of Texas at Austin. His books include The Power of African Cultures (2003), Economic Reforms and Modernization in Nigeria, 1945–1965 (2004), and A Mouth Sweeter than Salt: An African Memoir (2004). matthew m. heaton is a Patrice Lumumba Fellow at the University of Texas at Austin. He has co-edited multiple volumes on health and illness in Africa with Toyin Falola, including HIV/AIDS, Illness and African Well-Being (2007) and Health Knowledge and Belief Systems in Africa (2007). A HISTORY OF NIGERIA TOYIN FALOLA AND MATTHEW M. HEATON University of Texas at Austin CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521862943 © Toyin Falola and Matthew M.