Corruption in Nigeria: a Historical Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book-91249.Pdf

THE MILITARY IN NIGERIAN POLITICS (1966-1979): CORRECTIVE AGENT OR MERE USURPER OF POWER? By SHINA L. F. AMACHIGH " Bachelor of Arts Ahmadu Bello University Samaru-Zaria, Nigeria 1979 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate Col lege of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1986 THE MILITARY IN NIGERIAN POLITICS (1966-1979): CORRECTIVE AGENT OR MERE USURPER OF POWER? Thesis Approved: Dean of the Graduate College 1251198 i i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My foremost thanks go to my heavenly Father, the Lord Jesus Christ and the Holy Spirit for the completion of this study. Thank you, Dr. Lawler (committee chair), for your guidance and as sistance and for letting me use a dozen or so of your personal textbooks throughout the duration of this study. Appreciation is also expressed to the other committee members, Drs. von Sauer and Sare, for their in valuable assistance in preparation of the final manuscript. Thank you, Ruby and Amen (my wife and son) for not fussing all the times I had to be 11 gone again. 11 I love you. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I • INTRODUCTION Backqround 1 The Problem 2 Thesis and Purpose 2 Analytical Framework and Methodology 3 I I. REVIEW OF THEORETICAL LITERATURE 5 The Ataturk Model ....• 16 The Origins of Military Intervention 18 Africa South of the Sahara .... 20 I II. BRIEF HISTORY OF MILITARY INVOLVEMENT IN NIGERIAN POLITICS (1966-1979) 23 IV. THE PROBLEM OF NATIONAL INTEGRATION 29 British Colonialism and National Inte- gration in Nigeria .... -

Nigeria: Evidence of Corruption and the Influence of Social Norms

www.transparency.org www.cmi.no Nigeria: Evidence of corruption and the influence of social norms Query Can you provide an overview of corruption in Nigeria, presenting the existing evidence on what types of corruption take place in the country, at what levels of society, at what magnitude – and in particular, what social norms are involved? Purpose nepotism and cronyism, among others; and (ii) to preserve power, which includes electoral Contribute to the agency’s work in this area. corruption, political patronage, and judicial corruption. Content Evidence also suggests that these forms of 1. Introduction: The literature on corruption in corruption are related to the country’s social Nigeria norms. Nigeria is assessed as a neo-patrimonial state, where power is maintained through the 2. Social norms and corruption in Nigeria awarding of personal favours and where 3. Forms of corruption in Nigeria politicians may abuse their position to extract as 4. References many rents as possible from the state. Summary This answer provides an overview of the existing evidence regarding corruption and social norms, highlighting the main areas discussed in the literature related to the social mechanisms influencing corruption in the country, as well as an overview of existing evidence regarding the main forms of corruption that take place in Nigeria. Available evidence demonstrates that corruption in Nigeria serves two main purposes: (i) to extract rents from the state, which includes forms of corruption such as embezzlement, bribery, Author(s): Maíra Martini, Transparency International, [email protected] Reviewed by: Marie Chêne; Samuel Kaninda, Transparency International Acknowledgement: Thanks to the Civil Society Legislative Advocacy Centre (CISLAC) for their contribution. -

Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University In

79I /f NIGERIAN MILITARY GOVERNMENT AND PRESS FREEDOM, 1966-79 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Ehikioya Agboaye, B.A. Denton, Texas May, 1984 Agboaye, Ehikioya, Nigerian Military Government and Press Freedom, 1966-79. Master of Arts (Journalism), May, 1984, 3 tables, 111 pp., bibliography, 148 titles. The problem of this thesis is to examine the military- press relationship inNigeria from 1966 to 1979 and to determine whether activities of the military government contributed to violation of press freedom by prior restraint, postpublication censorship and penalization. Newspaper and magazine articles related to this study were analyzed. Interviews with some journalists and mili- tary personnel were also conducted. Materials collected show that the military violated some aspects of press freedom, but in most cases, however, journalists were free to criticize government activities. The judiciary prevented the military from arbitrarily using its power against the press. The findings show that although the military occasionally attempted suppressing the press, there are few instances that prove that journalists were denied press freedom. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES............ .P Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . 1 Statement of the Problem Purpose of the Study Significant Questions Definition of Terms Review of the Literature Significance of the Study Limitations Methodology Organization II. PREMILITARY ERA,.... 1865-1966...18 . From Colonial to Indigenous Press The Press in the First Republic III. PRESS ACTIONS IN THE MILITARY'S EARLY YEARS 29 Before the Civil War The Nigeria-Biaf ran War and After IV. -

Downloaded August 21, 2016

ETHNO-RELIGIOUS CONFLICT AND SETTLEMENT DYNAMICS IN PLATEAU STATE, NIGERIA, 1994-2012 BY ONYEKACHI ERNEST NNABUIHE B.A. (Imo), M.A. (Ibadan) A Thesis in PEACE and CONFLICT STUDIES Submitted to the Institute for Peace and Strategic Studies, in partial fulfilment for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of the UNIVERSITY OF IBADAN SEPTEMBER 2016 UNIVERSITY OF IBADAN LIBRARY i ABSTRACT Persistent communal conflicts in Plateau State underscore the differences between ethno-religious identities and aggravated segregation in human settlements. Existing studies on ethno-religious conflict have focused on colonial segregated settlement policy otherwise known as the Sabon Gari. These studies have neglected settlement dynamics as both cause and effect of ethno-religious conflicts. This study, therefore, interrogated the complex interaction between ethno-religious conflict and settlement dynamics in Plateau State. This is with a view to showing how conflicts structure and restructure settlements and their implications for inter-group relations, group mobilisation and infrastructural development. The study adopted Lawler‘s Relational theory and case study research design. Respondents were purposively selected from four Local Government Areas comprising Jos North, Jos South, Barkin- Ladi and Riyom. Primary data were collected through 46 in-depth interviews from twelve neighbourhood leaders, eleven ethno-religious group leaders, three members of civil society organisations, four estate managers, two security officials, two academics and twelve youth leaders. A total of six Focus Group Discussions were held: one each with Afizere, Anaguta and Hausa ethnic groups in Jos North, Berom in Jos South, Igbo in Barkin-Ladi and Fulani in Riyom. Non-participant observation method was also employed. -

Accredited Observer Groups/Organisations for the 2011 April General Elections

ACCREDITED OBSERVER GROUPS/ORGANISATIONS FOR THE 2011 APRIL GENERAL ELECTIONS Further to the submission of application by Observer groups to INEC (EMOC 01 Forms) for Election Observation ahead of the April 2011 General Elections; the Commission has shortlisted and approved 291 Domestic Observer Groups/Organizations to observe the forthcoming General Elections. All successful accredited Observer groups as shortlisted below are required to fill EMOC 02 Forms and submit the full names of their officials and the State of deployment to the Election Monitoring and Observation Unit, INEC. Please note that EMOC 02 Form is obtainable at INEC Headquarters, Abuja and your submissions should be made on or before Friday, 25th March, 2011. S/N ORGANISATION LOCATION & ADDRESS 1 CENTER FOR PEACEBUILDING $ SOCIO- HERITAGE HOUSE ILUGA QUARTERS HOSPITAL ECONOMIC RESOURCES ROAD TEMIDIRE IKOLE EKITI DEVELOPMENT(CEPSERD) 2 COMMITTED ADVOCATES FOR SUSTAINABLE DEV SUITE 18 DANOVILLE PLAZA GARDEN ABUJA &YOUTH ADVANCEMENT FCT 3 LEAGUE OF ANAMBRA PROFESSIONALS 86A ISALE-EKO WAY DOLPHIN – IKOYI 4 YOUTH MOVEMENT OF NIGERIA SUITE 24, BLK A CYPRIAN EKWENSI CENTRE FOR ARTS & CULTURE ABUJA 5 SCIENCE & ECONOMY DEV. ORG. SUITE KO5 METRO PLAZA PLOT 791/992 ZAKARIYA ST CBD ABUJA 6 GLOBAL PEACE & FORGIVENESS FOUNDATION SUITE A6, BOBSAR COMPLEX GARKI 7 CENTRE FOR ACADEMIC ENRICHMENT 2 CASABLANCA ST. WUSE 11 ABUJA 8 GREATER TOMORROW INITIATIVE 5 NSIT ST, UYO A/IBOM 9 NIG. LABOUR CONGRESS LABOUR HOUSE CBD ABUJA 10 WOMEN FOR PEACE IN NIG NO. 4 MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY KADUNA 11 YOUTH FOR AGRICULTURE 15 OKEAGBE CLOSE ABUJA 12 COALITION OF DEMOCRATS FOR ELECTORAL 6 DJIBOUTI CRESCENT WUSE 11, ABUJA REFORMS 13 UNIVERSAL DEFENDERS OF DEMOCRACY UKWE HOUSE, PLOT 226 CENSUS CLOSE, BABS ANIMASHANUN ST. -

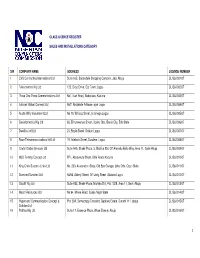

S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07

CLASS LICENCE REGISTER SALES AND INSTALLATIONS CATEGORY S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07 2 Telesciences Nig Ltd 123, Olojo Drive, Ojo Town, Lagos CL/S&I/002/07 3 Three One Three Communications Ltd No1, Isah Road, Badarawa, Kaduna CL/S&I/003/07 4 Latshak Global Concept Ltd No7, Abolakale Arikawe, ajah Lagos CL/S&I/004/07 5 Austin Willy Investment Ltd No 10, Willisco Street, Iju Ishaga Lagos CL/S&I/005/07 6 Geoinformatics Nig Ltd 65, Erhumwunse Street, Uzebu Qtrs, Benin City, Edo State CL/S&I/006/07 7 Dwellins Intl Ltd 21, Boyle Street, Onikan Lagos CL/S&I/007/07 8 Race Telecommunications Intl Ltd 19, Adebola Street, Surulere, Lagos CL/S&I/008/07 9 Clarfel Global Services Ltd Suite A45, Shakir Plaza, 3, Michika Strt, Off Ahmadu Bello Way, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/009/07 10 MLD Temmy Concept Ltd FF1, Abeoukuta Street, Bida Road, Kaduna CL/S&I/010/07 11 King Chris Success Links Ltd No, 230, Association Shop, Old Epe Garage, Ijebu Ode, Ogun State CL/S&I/011/07 12 Diamond Sundries Ltd 54/56, Adeniji Street, Off Unity Street, Alakuko Lagos CL/S&I/012/07 13 Olucliff Nig Ltd Suite A33, Shakir Plaza, Michika Strt, Plot 1029, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/013/07 14 Mecof Resources Ltd No 94, Minna Road, Suleja Niger State CL/S&I/014/07 15 Hypersand Communication Concept & Plot 29A, Democracy Crescent, Gaduwa Estate, Durumi 111, abuja CL/S&I/015/07 Solution Ltd 16 Patittas Nig Ltd Suite 17, Essence Plaza, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja CL/S&I/016/07 1 17 T.J. -

Money and Politics in Nigeria

Money and Politics in Nigeria Edited by Victor A.O. Adetula Department for International DFID Development International Foundation for Electoral System IFES-Nigeria No 14 Tennessee Crescent Off Panama Street, Maitama, Abuja Nigeria Tel: 234-09-413-5907/6293 Fax: 234-09-413-6294 © IFES-Nigeria 2008 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of International Foundation for Electoral System First published 2008 Printed in Abuja-Nigeria by: Petra Digital Press, Plot 1275, Nkwere Street, Off Muhammadu Buhari Way Area 11, Garki. P.O. Box 11088, Garki, Abuja. Tel: 09-3145618, 08033326700, 08054222484 ISBN: 978-978-086-544-3 This book was made possible by funding from the UK Department for International Development (DfID). The opinions expressed in this book are those of the individual authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of IFES-Nigeria or DfID. ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements v IFES in Nigeria vii Tables and Figures ix Abbreviations and Acronyms xi Preface xv Introduction - Money and Politics in Nigeria: an Overview -Victor A.O. Adetula xxvii Chapter 1- Political Money and Corruption: Limiting Corruption in Political Finance - Marcin Walecki 1 Chapter 2 - Electoral Act 2006, Civil Society Engagement and the Prospect of Political Finance Reform in Nigeria - Victor A.O. Adetula 13 Chapter 3 - Funding of Political Parties and Candidates in Nigeria: Analysis of the Past and Present - Ezekiel M. Adeyi 29 Chapter 4 - The Role of INEC, ICPC and EFCC in Combating Political Corruption - Remi E. -

Collective Action on Corruption in Nigeria

Chatham House Report Leena Koni Hoffmann and Raj Navanit Patel Collective Action on Corruption in Nigeria A Social Norms Approach to Connecting Society and Institutions Chatham House Report Leena Koni Hoffmann and Raj Navanit Patel Africa Programme | May 2017 Collective Action on Corruption in Nigeria A Social Norms Approach to Connecting Society and Institutions Chatham House, the Royal Institute of International Affairs, is an independent policy institute based in London. Our mission is to help build a sustainably secure, prosperous and just world. The Royal Institute of International Affairs Chatham House 10 St James’s Square London SW1Y 4LE T: +44 (0) 20 7957 5700 F: + 44 (0) 20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org Charity Registration No. 208223 © The Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2017 Chatham House, the Royal Institute of International Affairs, does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the author(s). All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. Please direct all enquiries to the publishers. ISBN 978 1 78413 217 0 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Typeset by Soapbox, www.soapbox.co.uk Printed and bound in Great Britain by City Print (Milton Keynes) Ltd The material selected for the printing of this report is manufactured from 100% genuine de-inked post-consumer waste by an ISO 14001 certified mill and is Process Chlorine Free. -

An Assessment of Civil Military Relations in Nigeria As an Emerging Democracy, 1999-2007

AN ASSESSMENT OF CIVIL MILITARY RELATIONS IN NIGERIA AS AN EMERGING DEMOCRACY, 1999-2007 BY MOHAMMED LAWAL TAFIDA DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA NIGERIA JUNE 2015 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis entitled An Assessment of Civil-Military Relations in Nigeria as an Emerging Democracy, 1999-2007 has been carried out and written by me under the supervision of Dr. Hudu Ayuba Abdullahi, Dr. Mohamed Faal and Professor Paul Pindar Izah in the Department of Political Science and International Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria. The information derived from the literature has been duly acknowledged in the text and a list of references provided in the work. No part of this dissertation has been previously presented for another degree programme in any university. Mohammed Lawal TAFIDA ____________________ _____________________ Signature Date CERTIFICATION PAGE This thesis entitled: AN ASSESSMENT OF CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS IN NIGERIA AS AN EMERGING DEMOCRACY, 1999-2007 meets the regulations governing the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science of the Ahmadu Bello University Zaria and is approved for its contribution to knowledge and literary presentation. Dr. Hudu Ayuba Abdullahi ___________________ ________________ Chairman, Supervisory Committee Signature Date Dr. Mohamed Faal________ ___________________ _______________ Member, Supervisory Committee Signature Date Professor Paul Pindar Izah ___________________ -

Impact of Corruption on Nigeria's Economy

Impact of Corruption on Nigeria's Economy www.pwc.com/ng Contents Executive summary 3 Introduction 4 Corruption and its impact on the economy 5 Methodology for creating scenarios 13 Results demonstrating the economic 14 cost of corruption in Nigeria Appendices 18 Scenario 1 18 Scenario 2 19 Scenario 3 20 Country case studies 21 Bibliography 23 Contacts 24 2 Impact of Corruption on Nigeria's Economy Executive summary Corruption is a pressing issue in Nigeria. In this report we formulate the ways in President Muhammadu Buhari launched which corruption impacts the Nigerian an anti-corruption drive after taking economy over time and estimate the impact office in May, 2015. Corruption affects of corruption on Nigerian GDP, using public finances, business investment as empirical literature and PwC analysis. We well as standard of living. Recent estimate the ‘foregone output’ in Nigeria corruption scandals have highlighted the since the onset of democracy in 1999 and large sums that have been stolen and/or the ‘output opportunity’ to be gained by misappropriated. But little has been 2030, from reducing corruption to done to explore the dynamic effects of comparison countries that are also rich in corruption that affect the long run natural resources. The countries we have capacity of the country to achieve its used for comparison are: Ghana, Colombia potential. Channels through which this and Malaysia. may occur include: Our results show that corruption in Nigeria Lower governance effectiveness, could cost up to 37% of GDP by 2030 if it’s especially through smaller tax base not dealt with immediately. This cost is and inefficient government equated to around $1,000 per person in expenditure. -

The Venus Medicare Hospital Directory

NATIONWIDE PROVIDER DIRECTORY CATEGORY 1 HOSPITALS S/N STATE CITY/TOWN/DISTRICT HEALTHCARE PROVIDER ADDRESS TERMS & CONDITIONS SERVICES Primary, O&G, General Surgery, Paediatrics, 1 FCT/ABUJA CENTRAL AREA Limi Hospital & Maternity Plot 541Central District, Behind NDIC/ICPC HQ, Abuja Nil Internal Medicine Primary, Int. Med, Paediatrics,O&G, GARKI Garki Hospital Abuja Tafawa Balewa Way, Area 3, Garki, Abuja Private Wards not available. Surgery,Dermatology Amana Medical Centre 5 Ilorin str, off ogbomosho str,Area 8, Garki Nil No.5 Plot 802 Malumfashi Close, Off Emeka Anyaoku Strt, Alliance Clinics and Services Area 11 Nil Primary, Int. Med, Paediatrics Primary, O&G, General Surgery, Paediatrics, Internal Medicine Dara Medical Clinics Plot 202 Bacita Close, off Plateau Street, Area 2 Nil Primary, O&G, General Surgery, Paediatrics, Internal Medicine Sybron Medical Centre 25, Mungo Park Close, Area 11, Garki, Abuja Nil Primary, O&G, Paediatrics,Int Medicine, Gen Guinea Savannah Medical Centre Communal Centre, NNPC Housing Estate, Area II, Garki Nil Surgery, Laboratory Bio-Royal Hospital Ltd 11, Jebba Close, Off Ogun Street, Area 2, Garki Nil Primary, Surgery, Paediatrics. Primary, Family Med, O & G, Gen Surgery, Royal Specialist Hospital 2 Kukawa Street, Off Gimbiyan Street Area 11, Garki, Abuja Nil Urology, ENT, Radiology, Paediatrics No.4 Ikot Ekpene Close, Off Emeka Anyaoku Street Crystal Clinics (opposite National Assembly Clinic) Garki Area 11 Nil Primary, O&G, Paediatrics, Internal Medicine, Surgery Model Care Hospital & Consultancy Primary, Paediatrics, Surgery and ENT Limited No 5 Jaba Close, off Dunukofia Street by FCDA Garki, Abuja Nil Surgery Primary, O&G, General Surgery, Paediatrics, GARKI II Fereprod Medical Centre Obbo Crescent, off Ahmadu Bello Way, Garki II Nil Internal Medicine Holy Trinity Hospital 22 Oroago Str, by Ferma/Old CBN HQ, Garki II Nil Primary only. -

The War Against Corruption in Nigeria: Devouring Or Sharing the National Cake?

Munich Personal RePEc Archive The war against corruption in Nigeria: devouring or sharing the national cake? NYONI, THABANI February 2018 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/87615/ MPRA Paper No. 87615, posted 29 Jun 2018 19:01 UTC THE WAR AGAINST CORRUPTION IN NIGERIA: DEVOURING OR SHARING THE NATIONAL CAKE? Thabani Nyoni Department of Economics, University of Zimbabwe, Harare, Zimbabwe Email: [email protected] Abstract That corruption abounds in Nigeria is an indisputable fact (Agbiboa, 2012). The corrupt man is everywhere, the man on the street, the man next door, the man in the church or mosque, the man in the market or the departmental store, the policeman on beat patrol and the soldier at the check point (Okadigbo, 1987). Corruption in Nigeria has passed the alarming and entered the fatal stage (Achebe, 1983). The rate of corruption is so high that the Federal House of Representative in Nigeria is now contemplating hanging for treasury looters as a solution to corruption (Ige, 2016). Corruption is a clog in the wheel of progress in Nigeria and has incessantly frustrated the realization of noble national goals, despite the enormous natural and human resources in Nigeria (Ijewereme, 2015). Corruption cases have been on the increase despite anti – corruption crusades (Izekor & Okaro, 2018). Corruption dynamics in Nigeria reveal that politicians and public office bearers in Nigeria have proven beyond any reasonable doubt that they are not able to translate their anti – corruption “gospel” into action; theirs is to devour rather than share the “national cake”. Today Nigerians continue to languish in extreme poverty and yet Nigeria is one of the few African countries with abundant natural and human resource endowments.