Around the World in Eighty Changes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Astronomy and Astronomers in Jules Verne's Novels

The Rˆole of Astronomy in Society and Culture Proceedings IAU Symposium No. 260, 2009 c 2009 International Astronomical Union D. Valls-Gabaud & A. Boksenberg, eds. DOI: 00.0000/X000000000000000X Astronomy and astronomers in Jules Verne’s novels Jacques Crovisier Observatoire de Paris, 5 place Jules Janssen, 92195 Meudon, France email: [email protected] Abstract. Almost all the Voyages Extraordinaires written by Jules Verne refer to astronomy. In some of them, astronomy is even the leading theme. However, Jules Verne was basically not learned in science. His knowledge of astronomy came from contemporaneous popular publications and discussions with specialists among his friends or his family. In this article, I examine, from the text and illustrations of his novels, how astronomy was perceived and conveyed by Jules Verne, with errors and limitations on the one hand, with great respect and enthusiasm on the other hand. This informs us on how astronomy was understood by an “honnˆete homme” in the late 19th century. Keywords. Verne J., literature, 19th century 1. Introduction Jules Verne (1828–1905) wrote more than 60 novels which constitute the Voyages Extraordinaires series†. Most of them were scientific novels, announcing modern science fiction. However, following the strong suggestions of his editor Pierre-Jules Hetzel, Jules Verne promoted science in his novels, so that they could be sold as educational material to the youth (Fig. 1). Jules Verne had no scientific education. He relied on popular publications and discussions with specialists chosen among friends and relatives. This article briefly presents several examples of how astronomy appears in the text and illustrations of the Voyages Extraordinaires. -

Planets, Comets and Small Bodies in Jules Verne's Novels

DPS-EPSC joint meeting Nantes, 2-7 October 2011 Planets, comets and small bodies in Jules Verne's novels J. Crovisier Observatoire de Paris LESIA, CNRS, UPMC, Université Paris-Diderot 5 place Jules Janssen, 92195 Meudon, France Jules Verne Nantes – 8 February 1828 Amiens – 24 March 1905 An original binding of Almost all the Voyages Extraordinaires written by Jules Verne refer to astronomy. In some of From the Earth to the Moon and Around the Moon them, astronomy is even the leading theme. However, Jules Verne was basically not learned in science. His knowledge of astronomy came from contemporaneous popular publications and discussions with specialists among his friends or his family. Here, we examine, from selected texts and illustrations of his novels, how astronomy — and especially planetary science — was perceived and conveyed by Jules Verne, with errors and limitations on the one hand, with great respect and enthusiasm on the other hand. Jules Verne was born in Nantes, where most of the manuscripts of his novels are now deposited in the municipal library. They were heavily edited by the publishers Pierre-Jules and Louis-Jules Hetzel, by Jules Verne himself, and (for the last ones) by his son Michel Verne. This poster briefly discusses how astronomy appears in the texts and illustrations of the Voyages Extraordinaires, concentrating on several examples among planetary science. More material can be found in the abstract and in the web page : http://www.lesia.obspm.fr/perso/jacques-crovisier/JV/verne_gene_eng.html De la Terre à la Lune (1865, From the Earth to the Moon) and Autour de la Lune (1870, Around Palmyrin Rosette, the free-lance The rival astronomers in The Chase of the Golden Meteor. -

Around the World in 80 Days. Jules Verne

Coradella Collegiate Bookshelf Editions. Around the World in 80 Days. Jules Verne. Open Contents Jules Verne. Around the World in 80 Days. than studying the law, he promptly withdrew his financial support. About the author Consequently, he was forced to support himself as a stockbroker, which he hated, although he was a success at it. During this period, he met the authors Alexandre Dumas and Victor Hugo, who offered Jules Verne (February 8, 1828 - him some advice on his writing. March 24, 1905) was a French writer It was during this period he met Honorine de Viane Morel, a and a pioneer of the science fiction widow with two daughters. They married on January 10, 1857. With (scientific romance) genre. her encouragement, he continued to write and actively try to find a Verne was born in Nantes to at- publisher. On August 4, 1861, their son, Michel Jean Pierre Verne, torney Pierre Verne and his wife was born. A classic enfant terrible, he married an actress over Verne’s Sophie. The oldest of the family's five objections, and had two children by his underage mistress. children, he spent his early years at Verne’s situation improved when he met Pierre-Jules Hetzel, one home with his parents, on a nearby of the most important French publishers of the 19th century, who island in the Loire River. published also Victor Hugo, George Sand, and Erckmann-Chatrian, This isolated setting helped to strengthen both his imagination among others. Hetzel read a draft of Verne’s story about the balloon and the bond between him and his younger brother Paul. -

Colloque Nouvelles Lectures Politiques De Jules Et Michel Verne Amiens, 17-18 Mars 2022 Cinquante Ans Après La Publication

Colloque Nouvelles lectures politiques de Jules et Michel Verne Amiens, 17-18 mars 2022 Cinquante ans après la publication par Jean Chesneaux d’Une lecture politique de Jules Verne, complété quelques années plus tard par de Nouvelles lectures politiques de Jules Verne, le sujet reste encore largement ouvert. Que l’œuvre de Jules Verne soit essentiellement politique est désormais admis dans la sphère académique. La découverte puis une lecture attentive des ouvrages posthumes, plus ou moins profondément remaniés par Michel, l’édition parallèle lorsque cela était possible du texte de Jules et de celui de Michel (Le Beau Danube jaune/Le Pilote du Danube ; En Magellanie/Les Naufragés du Jonathan ; Le Secret de Wilhelm Storitz ; Le Phare du bout du monde ; Le Volcan d’or, version originale et version revue) ont contribué à attirer l’attention sur un discours propre à Michel qui remet en lumière les choix de son père, de même que la génétique textuelle vernienne avait fait le départ entre marqueurs idéologiques propres à Jules et corrections de Hetzel. Mais rares demeurent les études disposées à creuser le sens politique de l’œuvre de Jules Verne, voire celui des ouvrages de Michel. La tentation est évidemment grande de vouloir politiser Verne ou les Verne, dans un sens qui serait celui de notre modernité : il est loisible d’aborder dans la perspective des post- colonial studies celui qui, des Enfants du capitaine Grant à Mistress Branican ou Un capitaine de quinze ans dénonçait avec virulence le génocide (on n’employait pas encore ce terme) perpétré par les colons anglais et qui s’est prononcé à de nombreuses reprises contre les « doctrines anti-humaines de l’esclavagisme » (Le Testament d’un excentrique). -

History of Vernian Studies

Submitted December 14, 2016 Published May 16, 2017 Proposé le 14 décembre 2016 Publié le 16 mai 2017 History of Vernian Studies Jean-Michel Margot Abstract The study of Jules Verne's œuvre began during his own lifetime. In 1966 his works came into the public domain and many French publishers began to reprint them in special editions. New, more accurate, translations soon followed, and Verne scholars discovered previously unpublished pieces. This history of Vernian studies is a chronological overview of research about Verne and his writings published in Europe and around the world, from the 19th century to today. It identifies a number of milestones in the publishing of Verne's works and it chronicles the rise and evolution of Vernian criticism. The purpose of this article is to aid new students and researchers interested in Jules Verne by enhancing their understanding of previous studies and to help them to avoid “reinventing the wheel” in their own research. Résumé L'étude de l'œuvre de Jules Verne a débuté du vivant de l'écrivain déjà. Il faut attendre 1966 pour voir son œuvre tomber dans le domaine public. De nombreux éditeurs le publient alors, de nouvelles traductions fiables apparaissent et les découvertes de textes inédits se multiplient. Cette histoire est une fresque chronologique des recherches et de leurs résultats dans le domaine vernien aussi bien en Europe que dans le reste du monde, des débuts jusqu'à nos jours. Elle rapporte les étapes cruciales de la publication des œuvres de Verne ainsi que les étapes de l'évolution des études verniennes. -

Ebook Download Around the World in 80 Days Ebook, Epub

AROUND THE WORLD IN 80 DAYS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jules Verne | 224 pages | 20 Nov 2008 | Sterling Juvenile | 9781402754272 | English | New York, United States Around the World in 80 Days PDF Book Verne's friend Jacques Arago had written a very popular Voyage autour du monde in The film premiered on October 17, at the Rivoli Theater in New York City [18] and played to full houses for 15 months. He rushes back to notify Fogg, who arrives at the Reform Club with only moments to spare. Retrieved March 10, Full Cast and Crew. Inspector Fix. Photo Gallery. Tom Bodman…. During the few hours before their planned departure for Calcutta on the Great India Peninsula Railway, Passepartout visits a Hindu temple on Malabar Hill , unaware that Christians are forbidden to enter and that shoes are not to be worn inside. Sail a burning Atlantic paddle-wheeler! Namespaces Article Talk. Watch on Prime Video included with Prime. Release date. Retrieved February 9, No ads. Molly MacPherson…. I'm gonna get it on DVD very soon. The train travels through India until stopping at the village of Kholby, where Fogg learns that, contrary to what was reported in the British press, the railroad is 50 miles 81 km short of completion, and passengers are required to find their own way to Allahabad to resume the train trip. However, the engineer believes that it might be possible to safely cross the bridge by going at top speed, and the plan works, with the bridge collapsing as soon as the train reaches the other side. -

Editorial — the Verne Translation Renaissance Continues

Editorial — The Verne Translation Renaissance Continues Arthur B. Evans Asked to write an editorial for Volume 5 of Verniana, I would like to give a brief update to the survey of Anglophone Vernian scholarship (1965-2007) that I contributed to Volume 1 of Verniana several years ago. [1] In particular, I’d like to take a moment to recognize those many scholars, fans, and publishers who have made 2008-2012 an especially rich period for new English-language translations of Jules Verne. Top kudos for recent translations must go to the indefatigable American Vernian from Albuquerque Frederick Paul Walter, not only for his impressive omnibus volume Amazing Journeys: Five Visionary Classics published in 2010 (containing new translations of Journey to the Center of the Earth, From the Earth to the Moon, Circling the Moon, 20,000 Leagues Under the Seas, Around the World in 80 Days) but also for his “first complete English translation” of Verne’s The Sphinx of the Ice Realm (also featuring the full text of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym) which appeared in 2012. Both were published by Excelsior Editions, an imprint of SUNY Press. Equally indefatigable is Brian Taves, president of the North American Jules Verne Society and editor of its excellent Palik Series. He continues to lead a talented team of translators (Edward Baxter, Kieran M. O’Driscoll, and Frank Morlock et al.) and world-class Verne scholars (Jean-Michel Margot, Volker Dehs, and Garmt de Vries-Uiterweerd et al.) in their quest to “bring to the Anglo-American public [...] hitherto unknown Verne tales” (see their website at http://www.najvs.org/palikseries-press.shtml). -

Review of Jules Verne's Journey Through the Impossible, Trans

DePauw University Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University Modern Languages Faculty publications Modern Languages 11-2004 Verne on Stage. [Review of Jules Verne's Journey Through the Impossible, trans. Edward Baxter, ed. Jean-Michel Margot, Prometheus, 2003 Arthur B. Evans DePauw University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.depauw.edu/mlang_facpubs Part of the Modern Literature Commons Recommended Citation Arthur B. Evans. "Verne on Stage." [Review of Jules Verne's Journey Through the Impossible, trans. Edward Baxter, ed. Jean-Michel Margot. Prometheus, 2003] Science Fiction Studies 31.3 (2004): 479-480. This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Modern Languages at Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern Languages Faculty publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Science Fiction Studies #94 = Volume 31, Part 3 = November 2004 Verne on Stage. Jules Verne. Journey Through the Impossible. Trans. Edward Baxter. Ed. Jean-Michel Margot. Artwork Roger Leyonmark. Amherst, NY: Prometheus, 2003. 181pp. $21.00 hc. I have been remiss in not mentioning earlier this excellent little book, the first English translation of an 1882 play by Jules Verne that shows him at his most whimsically science-fictional. It features on-stage journeys to the center of the Earth, beneath the seas to Atlantis, and through outer space to the planet Altor. The cast of characters in Journey recycles a host of recognizable Vernian heroes such as Professor Lidenbrock, Captain Nemo, Impey Barbicane and J.T. -

In the Year 2889

Submitted October 18, 2017 Published November 30, 2017 Proposé le 18 octobre 2017 Publié le 30 novembre 2017 “2889” vs. “2890” Arthur B. Evans Abstract This article offers a detailed comparison of Michel Verne’s 1889 short story “In the Year 2889” and Jules Verne’s 1891 recycled version of the same story, now called « La Journée d’un journaliste américain en 2890 » [The Day of an American Journalist in 2890]. In my analysis, I have also pointed out some of the alterations Michel made to his father’s version when later editing it for inclusion in the posthumous 1910 edition of Verne’s Hier et demain [Yesterday and Tomorrow], now retitled « Au XXIXe siècle : La Journée d’un journaliste américain en 2889 » [In the 29th Century: The Day of an American Journalist in 2889]. Résumé Cet article propose une comparaison détaillée de la nouvelle de 1889 de Michel Verne “In the Year 2889” [En l'an 2889] et de la version de Jules Verne recyclée en 1891 de la même histoire, maintenant intitulée « La Journée d’un journaliste américain en 2890 ». Dans mon analyse, j'ai également souligné certaines des modifications que Michel a apportées à la version de son père en l'éditant plus tard pour l'inclure dans l'édition posthume de Hier et demain de Verne, cette fois intitulée « Au XXIXe siècle : La Journée d’un journaliste américain en 2889 ». 155 156 Verniana – Volume 10 (2017-2018) Introduction During the almost four decades since the publication of Piero Gondolo della Riva’s 1978 bombshell article on the topic [1], a great deal of attention and moral outrage has been directed at Michel Verne for rewriting his father’s posthumous works. -

Lewintro.Pdf

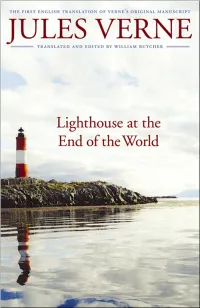

7>HDC;GDCI>:GHD;>B6<>C6I>DC JULES VERNE Lighthouse at the End of theWorld Le Phare du bout du monde The First English Translation of Verne’s Original Manuscript Translated and edited by William Butcher JC>K:GH>IND;C:7G6H@6EG:HH•A>C8DAC Publication of this book was made possible by a grant from The Florence Gould Foundation. Le Phare du bout du monde © Les Éditions internationales Alain Stanké, 1999. © Editions de l’Archipel. Translation and critical apparatus © 2007 by William Butcher. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Verne, Jules, 1828–1905. [Le phare du bout du monde. English] Lighthouse at the end of the world = Le phare du bout du monde : the first English translation of Verne’s original manuscript / Jules Verne ; translated and edited by William Butcher. p. cm. — (Bison frontiers of imagination) Includes bibliographical references. isbn-13: 978-0-8032-4676-8 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn-13: 978-0-8032-6007-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) I. Butcher, William, 1951– II. Title. III. Title: Le phare du bout du monde. pq2469.p4e5 2007 843'.8—dc22 2007001717 Set in Adobe Garamond by Kim Essman. Designed by R. W. Boeche. contents Introduction vii A Chronology of Jules Verne xxxiii Map of Staten Island xxxix 1.Inauguration 1 2. Staten Island 10 3. The Three Keepers 19 4.Kongre's Gang 30 5. The Schooner Maule 41 6. At Elgor Bay 50 7.The Cavern 61 8. Repairing the Maule 70 9.Vasquez 79 10.After the Wreck 89 11.The Wreckers 99 12. -

The Aquarian Theosophist, March 2019 2

The Aquarian Theosophist Volume XIX, Number 05, March 2019 The monthly journal of the Independent Lodge of Theosophists and its associated websites Blog: www.TheAquarianTheosophist.com E-mail: [email protected] 000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 The Golden Stairs Summing Up the Rules of Sacred Learning A ladder to the highest Robert Crosbie wrote: “An open mind, an eager intellect, without doubt or fear, is the unveiled spiritual perception.”[1] Crosbie was thus commenting the opening words of the “Golden Stairs”, a document Helena Blavatsky shared with her esoteric students in the 19th century. The Stairs constitute a summary of the rules to be followed by aspirants to discipleship in Eastern esoteric tradition. It is a short and decisive text. Students use to memorize its words, in order to have a permanent access to it, anytime, anywhere. The Aquarian Theosophist, March 2019 2 A few introductory sentences precede the Stairs. Although most people do not pay attention to them, these ideas are of fundamental importance in the eyes of those who have good sense. The introduction clarifies: “He who wipeth not away the filth with which the parent’s body may have been defiled by an enemy, neither loves the parent nor honours himself. He who defendeth not the persecuted and the helpless, who giveth not of his food to the starving nor draweth water from his well for the thirsty, hath been born too soon in human shape. Behold the truth before you.” Then the Golden Stairs say: A clean life, -

Jules Verne the Biography William Butcher Foreword by Arthur C

4 Jules Verne The Biography William Butcher Foreword by Arthur C. Clarke 7 Abbreviations ADF: Marguerite Allotte de la Fuÿe, Jules Verne JES: Verne, Journey to England and Scotland BSJV: Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne CNM: Charles-Noël Martin, La Vie et l’œuvre de Jules Verne (The Life and Works of Jules Verne) Int.: Entretiens avec Jules Verne (Interviews) JD: Joëlle Dusseau, Jules Verne JJV: Jean Jules-Verne, Jules Verne JVEST: Jean-Michel Margot (ed.), Jules Verne en son temps (Jules Verne in his Time) Lemire: Charles Lemire, Jules Verne MCY: “Memories of Childhood and Youth” OD: Olivier Dumas, Voyage à travers Jules Verne (Journey through Jules Verne) Poems: Poésies inédites (Unpublished Poems) PV: Philippe Valetoux, Jules Verne: En mer et contre tous (Jules Verne: All at sea and odds) RD: Raymond Ducrest de Villeneuve, untitled biography St M.: Verne’s list of journeys on the St Michel II and III TI: Théâtre inédit (Unpublished Plays) 291 Appendices A: Home Addresses Date Address 8 February 1828 Third floor, 4 Rue de Clisson, Nantes Late 1828 or early 1829 Second floor, 2 Quai Jean Bart October 1834 Mme Sambin’s pension, 5 Place du Bouffay About 1837 29 Rue des Réformés, Chantenay 3 October 1837 or St Stanislas School October 1836 About 1840 Second floor, 6 Rue Jean-Jacques Rousseau October 1840 St Donatien Junior Seminary 11 July 1848 (until 3 Probably near Henri Garcet’s, Fifth August) Arrondissement, Paris 12 November 1848 About fifth floor, 24 Rue de l’Ancienne Comédie, Sixth March 1849 Third floor, 24 Rue de l’Ancienne Comédie,