Legal Study on Community Rights and ICH Intellectual Property Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Beer Menu

Chestnut Tavern Drafts India Pale Ales (IPAs) and American Pale Ales (APAs) Blue Moon, Belgian Style Wheat, Golden, CO 6.75 Dogfish Head 90 Minute, Imperial IPA, Milton, DE 9.25 Brewed with Valencia orange peel. Subtle sweetness, citrus aroma. 5.4% 9 IBU Rich pine and fruity citrus hop aromas, with a strong malt backbone. 9% 90 IBU Flying Fish Salt & Sea, Strawberry Lime Session Sour, Somerdale, NJ 4.5 Lagunitas IPA, West Coast IPA, Petaluma, CA 6.5 Fruity with a bit of tang - very summer friendly. Think refreshing salt water taffy! 4.3% 8 IBU Well-rounded, with caramel malt barley for balance with twangy hops. 6.2% 51 IBU Guinness Draught, Irish Dry Stout, Dublin, IRL 7.75 Logyard Proper Notch, 2x NEIPA, Kane, PA 11.25 Rich and creamy, velvety in finish, and perfectly balanced. 4.2% 45 IBU Hazy, juicy, and dangerously well-balanced. Grapefruit on the nose, with smooth flavor and light hop bitterness. 8.1% 83 IBU Wallenpaupack Brewing, Largemouth IPA , Hawley, PA 8.25 Brewed with Chinook, Simcoe, and Citra hops for the perfect combination of dank citrus Magic Hat #9, Apricot Pale Ale, Burlington, VT 6.25 and pine bitterness. Brewed less than 1 mile away! 6.5% 65 IBU Notes of fruity and floral hops, with a touch of apricot sweetness. A pale ale and fruit beer hybrid. Refreshing and perfect for Spring! 5.1% 20 IBU New Trail Broken Heels, IPA, Williamsport, PA 8.25 Juicy, fruity, and delicious! Tropical and citrus notes prevail, with a smooth mouthfeel New Trail Broken Heels, IPA, Williamsport, PA 10.25 from the oats. -

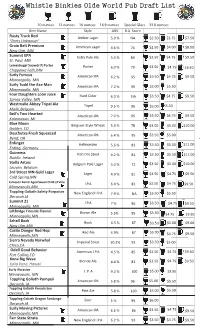

Master NORTH TAP LIST (7)!!!

Whistle Binkies Olde World Pub Draft List 10 ounces 12 ounces 16 ounces 16.9 ounces Special Glass 33.8 ounces Beer Name Style ABV B.A. Score Rusty Truck Red Amber Lager 5.0 % NA $2.50 $3.75 $7.50 “Parts Unknow n” Grain Belt Premium American Lager 4.6 % 74 $2.50 $4.00 $8.00 New U lm, M N Summit EPA Extra Pale Ale 5.3 % 84 $3.50 $4.75 $9.50 St. Paul, M N South X SouthEast Thirst Burst Sour Smoothie 4.6 % NA $3.50 $5.00 Pine Island, MN Surly Furious American IPA 6.2 % 95 $3.50 $4.75 $9.50 Minneapolis, M N Surly Todd the Axe Man American IPA 7.2 % 99 $5.00 $5.50 Minneapoli s, MN Four Daughters Loon Juice Hard Cider 6.0 % NA $3.50 $4.75 $9.50 Spring Valley, M N Westmalle Abbey Tripel Ale Trappist Tripel 9.5 % 96 $5.00 $5.50 Malle,Belguim Bell’s Two Hearted American IPA 7.0 % 95 $3.50 $4.75 $9.50 Kalamazoo, M I Blue Moon Belgium-Style Wheat 5.4 % 78 $3.00 $5.00 $10.00 Golden, CO Deschutes Fresh Squeezed American IPA 6.4 % 95 $3.50 $5.00 Bend, O R Erdinger Hefeweizen 5.6 % 81 $3.50 $5.50 $11.00 Erding, Germa ny Guinness Irish Dry Stout 4.2 % 81 $3.50 $5.50 $11.00 Dublin, Irelan d Stella Artois Belgium Pale Lager 5.0 % 72 $3.50 $5.00 $10.00 Leuven, Belgiu m 3rd Street MN Gold Lager Lager 4.9 % 81 $3.50 $4.75 $9.50 Cold Spring,MN Fulton War & Peace Russian Imperial Stout 9.5 % 93 $4.50 $5.00 Minneapolis,MN Toppling Goliath Imperial Golden New England I.P.A 8% 93 $3.50 $5.50 Decorah,IA Summit 21 I.P.A 7 % 86 $3.50 $4.75 $9.50 Minneapolis, MN Fulton Coffee Dopplebock Dopplebock 7.75% 74 $3.50 Minneapolis, MN $5.00 $9.00 Schell Bock Bock 6.5 % 87 $3.50 $5.00 $9.00 New Ulm,MN Castle Danger White Pine I.P.A. -

Creature Comforts / Classic City Lager

DRAFT CREATURE COMFORTS / CLASSIC CITY LAGER ..................................................................................................................... 3/5 Pale Lager / 4.2% ABV / 20 IBU 5oz • 12oz Good Cold Beer. MODERN TIMES / ABADDON ...................................................................................................................................................... 3/5 Helles Lager / 5.5% ABV / 28 IBU 5oz • 12oz Our brewers in Portland got together with our homies at Wayfinder Beer to create this stellar Helles. Naturally carbonated through a method called "spunding," this lager is beautifully bright and effervescent, with subtle hints of toasted bread and honey. Ridiculously drinkable and balanced, Abaddon was brewed with German malts and hopped with Perle abd Hallertau Mittlefruh to give it an expressive take on a traditional style. BURIAL / HELLSTAR ........................................................................................................................................................................ 3/5 Dunkel Lager / 4.8% ABV / 18 IBU 5oz • 16oz Cast into the clutches of eternal damnation. And crucified by all the noise. It’s dark lager. You need to have it but you don’t know it yet. You're infested with deceit. Someone told you that all black beer is heavy. Well that's just stupid. Oh we're as heavy as the chains of Hell. But this beer ain't. Open your heart to evil. Sip on the depths of our black souls. OTHER HALF / DDH MYLAR BAGS ...................................................................................................................................... -

Westmalle Trappist Product Sheet

Merchant du Vin, America's Premier Specialty Beer Importer since 1978 merchantduvin.com The Westmalle Abbey, north of Antwerp in Flanders, Belgium, was founded in 1794 and began to brew beer in 1836. The brewery is one of only seven Trappist breweries in the world, and is renowned for defining the Dubbel (or Double) and Tripel (or Triple) styles. All ingredients used are selected and processed with utmost care: barley malt, hops, pure liquid Belgian candi sugar, yeast and natural groundwater from the Abbey well. The brewers take great pride in maintaining careful control over the brewing process - all hops are added by hand and no chemical additives of any kind are found in Westmalle ales: they are the flavor of nature, of tradition, and of dedication. Westmalle Dubbel: Amber-brown color, with a subtle deep-caramel aroma and flavor balanced by Belgian yeast character. Deeply malty, with a dry finish that hints at tropical fruit, this is the classic Belgian Double, or in Flemish "Dubbel." Bottle-conditioned. Westmalle Dubbel 11.2 oz. (330 ml) Food-pairing suggestions: sweeter soft cheeses, beef rémoulade, rich sauces, or after dinner with espresso. Package sizes: 12/11.2 oz. (330 ml) bottles; 6/25.4 oz. (750 ml) bottles. Westmalle Dubbel 25.4 oz. (750 ml) 7% alc./vol. - OG 1.063 - IBU 24 Westmalle Tripel: The benchmark Tripel? Yes, according to many tasters and beer aficionados. Powerfully drinkable, glowing deep-gold color, and herbal aroma that suggests candied orange. Complex flavors of herb notes, rich malt sweetness, Saaz hops, Westmalle Tripel and warmth. -

Cni January 23

January 23, 2021 Image of the day Motor cycle racing suspended in NI… …and so is in person worship [email protected] Page 1 January 23, 2021 Church services to remain suspended - Church of Ireland Bishops in NI The bishops write - As you will be aware, yesterday afternoon the Northern Ireland Executive took the unanimous decision to extend the current Covid–19 restrictions until Friday 5th March 2021. This decision was based on the strong recommendation of the Chief Medical Officer and the Chief Scientific Advisor, as a result of the continued extremely high level of transmission of the Covid–19 virus throughout the community (which over these last four weeks had not reduced to the level that had been hoped for), along with the increasing numbers in hospital and intensive care. In the light of this decision, and on the basis of the clear and unequivocal public health advice that people should [email protected] Page 2 January 23, 2021 continue to stay at home, we have decided that all in person Sunday gatherings for worship, along with all other in person church gatherings, should remain suspended in all Church of Ireland parishes in Northern Ireland until Friday 5th March 2021 – with the exception of weddings, funerals, arrangements for recording and/or live–streaming, drive–in services and private prayer (as permitted by regulations).This same step is also being taken today by the Methodist Church, the Presbyterian Church, and the Roman Catholic Church. While we acknowledge that there is both cost and disappointment in this for many, we see this decision as part of our response to the command of Jesus to love our neighbours. -

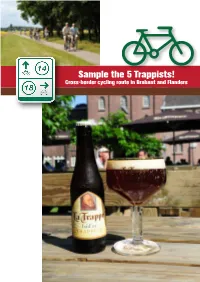

Taste Abbeyseng

Sample the 5 Trappists! Cross-border cycling route in Brabant and Flanders The Trappist region The Trappist region ‘The Trappists’ are members of the Trappist region; The Trappist order. This Roman Catholic religious order forms part of the larger Cistercian brotherhood. Life in the abbey has as its motto “Ora et Labora “ (pray and work). Traditional skills form an important part of a monk’s life. The Trappists make a wide range of products. The most famous of these is Trappist Beer. The name ‘Trappist’ originates from the French La Trappe abbey. La Trappe set the standards for other Trappist abbeys. The number of La Trappe monks grew quickly between 1664 and 1670. To this today there are still monks working in the Trappist brewerys. Trappist beers bear the label "Authentic Trappist Product". This label certifies not only the monastic origin of the product but also guarantees that the products sold are produced according the traditions of the Trappist community. More information: www.trappist.be Route booklet Sample the 5 Trappists Sample the 5 Trappists! Experience the taste of Trappist beers on this unique cycle route which takes you past 5 different Trappist abbeys in the provinces of North Brabant, Limburg and Antwerp. Immerse yourself in the life of the Trappists and experience the mystical atmosphere of the abbeys during your cycle trip. Above all you can enjoy the renowned Brabant and Flemish hospitality. Sample a delicious Trappist to quench your thirst or enjoy the beautiful countryside and the towns and villages with their charming street cafes and places to stay overnight. -

Annual Report of the Commissioners of the Massachusetts Nautical School

Public Document No. 42 MASS THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS QOCS'. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION COLL. ANNUAL REPORT THE COMMISSIONERS MASSACHUSETTS NAUTICAL SCHOOL FOR THE Year Ending November 30, 1939. Massachusetts Nautical School 100 Nashua Street, Boston Publication of this Document Approved by the Commission on Administration and Finance. 800—3-' 40. D— 1069. ®lj* Glnrnmnttwraltlj at HJassarljus^ttfi DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Walter F. Downey, Commissioner of Education COMMISSIONERS OF THE MASSACHUSETTS NAUTICAL SCHOOL 100 Nashua Street, Boston Clarence E. Perkins, Chairman Theodore L. Storer Walter K. Queen William H. Dimick, Secretary REPORT OF THE COMMISSIONERS To the Commissioner of Education: The Commissioners of the Massachusetts Nautical School have the honor to submit their report for the year ending November 30, 1939, the forty-eighth annual report. School Calendar, 1939 Spring entrance examinations March 30, 31, April 1 Spring graduation April 4 Winter term ended April 4 New class reported April 20 Leave, 1st section April 4 to 18 Leave, 2nd section April 18 to May 2 Summer term commenced May 2 "Nantucket" sailed from Boston May 13 "Nantucket" arrived at Boston September 18 Autumn entrance examinations _ September 21, 22, 23 Autumn graduation September 26 Summer term ended September 26 New class reported October 23 Leave, 1st section September 29 to October 13 Leave, 2nd section October 13 to 27 Winter term commenced October 27 Establishment and Purpose of the School In 1874 Congress passed an Act to encourage the establishment of nautical schools. The Act authorized the Secretary of the Navy to furnish a suitable vessel, with all her equipment, to certain States for use in maintaining a nautical school. -

Gaymers Far from Home Brochure

Index ------------------------ Far From What? P3 ________ Where From Home? P4 ________ Introduction Far From How Much? It took a while, but in 2022 it’s finally happening! The Gaymers are venturing on their biggest adventure yet! After many cozy game P4 nights, we will take the fun Far From Home! ________ Now you may be wondering what to expect? Then continue reading this brochure! We might even reveal some secrets. Furthermore, What From Home? you’ll find a wide array of practical information. Some things may be P5 obvious, but please read this brochure very carefully. We shall write ________ this only once. Do you still have any questions? Then don’t hesitate to contact one of the organizing members ORGANIZING TEAM Team leaders: Daan Vanden Eede en Jelle Smans Planning team 2021-2022: Daan Vanden Eede, Jelle Smans, John van der Aa, Nick Lukas, Siemen Bastens and Tim Spruijt. First Aid: Siemen Bastens – [email protected] For all your questions: [email protected] Read this brochure carefully, and you might catch the 4 hidden game references. 2 Gaymers Far From Home - 15/04/2022 till 19/04/2022 – www.gaymers.eu/events/gaymers-far-from-home Far From What? Far From Home, an extra long weekend, a “glamping experience” if you will, full of games, coziness, big games (yes, IRL), and much, much more! You’re welcome on Friday April 15th 2022, from 15h00. Once you’re installed and aren’t low on RAM to receive the latest update, then the fun can begin! Most of the time you can play whatever you desire. -

Master NORTH TAP LIST (7)

Whistle Binkies Olde World Pub Draft List 10 ounces 12 ounces 16 ounces 16.9 ounces Special Glass 33.8 ounces Beer Name Style ABV B.A. Score Rusty Truck Red Amber Lager 5.0 % NA $2.50 $3.75 $7.50 “Parts Unknow n” Grain Belt Premium American Lager 4.6 % 74 $2.50 $4.00 $8.00 New U lm, M N Summit EPA Extra Pale Ale 5.3 % 84 $3.50 $4.75 $9.50 St. Paul, M N Leinenkugel Snowdrift Porter Porter 6.0 % 79 $3.50 $4.75 $9.50 Chippewa Falls,MN Surly Furious American IPA 6.2 % 95 $3.50 $4.75 $9.50 Minneapolis, M N Surly Todd the Axe Man American IPA 7.2 % 99 $5.00 $5.50 Minneapoli s, MN Four Daughters Loon Juice Hard Cider 6.0 % NA $3.50 $4.75 $9.50 Spring Valley, M N Westmalle Abbey Tripel Ale Tripel 9.5 % 96 $5.00 $5.50 Malle,Belguim Bell’s Two Hearted American IPA 7.0 % 95 $3.50 $4.75 $9.50 Kalamazoo, M I Blue Moon Belgium-Style Wheat 5.4 % 78 $3.00 $5.00 $10.00 Golden, CO Deschutes Fresh Squeezed American IPA 6.4 % 95 $3.50 $5.00 Bend, O R Erdinger Hefeweizen 5.6 % 81 $3.50 $5.50 $11.00 Erding, Germa ny Guinness Irish Dry Stout 4.2 % 81 $3.50 $5.50 $11.00 Dublin, Irelan d Stella Artois Belgium Pale Lager 5.0 % 72 $3.50 $5.00 $10.00 Leuven, Belgiu m 3rd Street MN Gold Lager Lager 4.9 % 81 $3.50 $4.75 $9.50 Cold Spring,MN Jameson Barrel Aged Sweet Child of Vine I.P.A 6.4 % 83 $3.50 $4.75 $9.50 Minneapolis,MN Toppling Goliath Safety Porpoises New England I.P.A 7.9 % NA $3.50 $5.50 Decorah,IA Summit 21 I.P.A 7 % 86 $3.50 $4.75 $9.50 Minneapolis, MN LiftBridge Fireside Flannel Brown Ale 5.5% 85 $3.50 Minneapolis,MN $4.75 $9.50 Schell Bock Bock 6.5 % 87 $3.50 $5.00 $9.00 New Ulm,MN Castle Danger Red Hop Red Ale 6.9% 87 $5.00 Minneapolis,MN $4.75 $9.50 Sierra Nevada Narwhal Imperial Stout 10.2% 93 $3.50 $5.00 Chico,CA Odell Good Behavior American I.P.A 4.5 % 85 $3.50 $4.75 $9.50 Fort Collins,CO Kona Big Wave Blonde Ale 4.4 % 81 $3.50 $4.75 $9.50 Kaila Kona, Hawaii Surly Abrasive I. -

Westmalle Triple

Drankenspecialist van Rooij - Chopinplein 7 Phone: 0345-514374 - Email: [email protected] Culemborg Westmalle Triple Beschikbaarheid: Op voorraad Prijs: € 2.00 Beschrijving Westmalle Triple Westmalle is een trappistenbier dat in de abdij Onze-Lieve-Vrouw van het Heilig Hart van Westmalle wordt gebrouwen. Het klooster van Westmalle werd in 1836 tot abdij van de orde der trappisten verheven. In hetzelfde jaar begonnen de monniken met het brouwen van bier, aanvankelijk alleen voor eigen gebruik, maar vanaf 1856 ook voor de verkoop. De brouwerij is sindsdien diverse malen uitgebreid en gemoderniseerd, de laatste keer in 2001. bron: Wikipedia English Westmalle Triple Westmalle Brewery (Brouwerij der Trappisten van Westmalle) is a Trappistbrewery in the Westmalle Abbey, Belgium. It produces three beers, designated as Trappist beer by the International Trappist Association. Westmalle Tripel is credited with being the first golden strong pale ale to use the term Tripel. The Trappist abbey in Westmalle (officially called Abdij Onze-Lieve-Vrouw van het Heilig Hart van Jezus) was founded 6 June 1794, but the community was not elevated to the rank of Trappist abbey until 22 April 1836. Martinus Dom, the first abbot, decided the abbey would brew its own beer, and the first beer was brewed on 1 August 1836 and first imbibed on 10 December 1836. The pioneer brewers were Father Bonaventura Hermans and Albericus Kemps. The first beer was described as light in alcohol and rather sweet. By 1856, the monks had added a second beer: the first strong brown beer. This brown beer is today considered the first double (dubbel, in Dutch). -

MODESTE ØLFESTIVAL, ANTWERPEN, WESTMALLE TRAPPIST, BRYGGERI- BESØG Samt Mulighed for at Købe Gode Øl Med Hjem

og oplev bl.a. MODESTE ØLFESTIVAL, ANTWERPEN, WESTMALLE TRAPPIST, BRYGGERI- BESØG samt mulighed for at købe gode øl med hjem Rejsen arrangeres i samarbejde med Danske Ølentusiaster, Lokalafdeling Esbjerg. Kære interesserede. Yderligere oplysninger: For 6. gang udbyder jeg en rejse til øl-landet Leif Buster Hansen: Belgien. Denne rejse gør det muligt at opleve 75 14 55 20 / 51 49 44 87. den gamle diamant handelsby, Antwerpen På denne rejse skal vi bo på men det er også muligt at deltage i den for- Hotel Eden Antwerp holdsvis nye ølfestival i selve Antwerpen: Lange Herentalsestraat 25 MODESTE BIER FESTIVAL, - med gode 2018 Antwerpen, BELGIUM specialøl fra små bryggerier, som normalt Værelserne er enten dobbeltværelser med 1 ikke deltager på de større festivaler. dobbeltseng eller twinværelse med 2 stk. en- Men hvis du ikke er til øl, er det muligt at tage keltsenge. med og blot være turist og opleve de mange Desuden er der fladskærms-TV med alle de seværdigheder og butikker Antwerpen byder bedste kanaler og et badeværelse med walk-in på. brusebad. DELTAGERPRIS: 2595,- Dobbeltværelserne anvendes også som enkeltværelser mod tillæg. Deltagerprisen inkluderer transport Esbjerg / Stor morgenmadsbuffet og desuden gratis Kolding - Belgien og retur i moderne turistbus kaffe og te til rådighed hele dagen. og er baseret på indkvartering i delt dobbelt- værelse med bad og toilet, telefon og TV mv. samt 3 gange morgenbuffet. Desuden er det muligt at deltage i udflugten / indkøbsturen til ølhandelen om lørdagen. Tillæg for enkeltværelse: kr.: 790,- Turen er en ”non-profit”-tur, hvilket betyder, at jeg ikke har fortjeneste på turen. -

The Basket Build a Picnic Basket Receive a Basket for Your Picnic with a Minimum Spend of $60

the basket Build a Picnic Basket Receive a basket for your picnic with a minimum spend of $60. sandwiches bites & boxes Goat Cheese / Fig / Arugula / Ficelle 12 Olives & Hummus 11 Proscuitto / Brie / Olive Salad / Baguette 14 Calabrese / Brie / Honey / Crackers 11 Ham / Gruyère / Baguette 14 Sopressata / Cheddar / Fig / Crackers 11 sweets Chorizo / Manchego / Almonds / Crackers 11 Chicken Skewer / Togarashi / Asian Slaw 4 /12 Brownie 5 Crispy Mac & Cheese Bites (4) Blondie 5 12 wine on tap Quinet, Melon de Bourgogne 9 Sabine, Rosé 9 Muscadet, France '16 Provence, France '17 Vezzi, Barbera 9 Argyle, Pinot Noir 15 Piedmont, Italy '16 Willamette, Oregon '16 MacRostie, Chardonnay 14 Halter Ranch, Grenache Blanc 15 Sonoma Coast, California '16 Paso Robles, California '16 Bonny Doon, Grenache 15 El Rede, Malbec 9 Clos de Gilroy, Central Coast '16 Mendoza, Argentina '17 beverages beer & cider Maeloc Pear Cider, 11.2 oz, 4% abv 12 Frosé 13 Estrella Galicia, Galicia, Spain Freaujolais 13 Collective Arts Brewing Japanese Rice Lager, 12 Friezling 13 16 oz, 4.9% abv Collective Arts Brewing, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada Frozcato 13 Krombacher Weizen, 11.2 oz, 5.3% abv 11 Krombacher Brauerei, Kreuztal-Krombach, Germany Free frozen beverage with purchase of a Corkcicle Bell‘s Two Hearted IPA, 12 oz, 7% abv 12 Bell’s Brewery, Kalamazoo, Michigan, USA Coke, Diet Coke, Sprite 3.5 Duchesse de Bourgogne Flemish Red-Brown Ale, 14 3.5 Iced Tea 11.2 oz, 6% abv Brouwerij Verhaeghe, Vichte, West Flanders, Belgium Juice Box 2.5 Westmalle Tripel Trappist Ale , 11.2 oz, 9.5% abv 16 Coffee 3.5 Brouwerij der Trappisten van Westmalle, Westmalle Abbey, Belgium smartwater 6 Delirum Nocturnum Belgian Strong Dark Ale, 16 Dasani 4 11.2 oz, 8.5% abv Brouwerij Huyghe, Melle, East Flanders, Belgium Cappuccino 5.5 Left Hand Milk Stout Nitro, 13.65 oz, 8.5% abv 12 Espresso 3.5 Left Hand Brewing, Longmont, Colorado, USA WWW.WINEBARGEORGE.COM | @WINEBARGEORGE | #WINEBARGEORGE | Q D E.