Using Technology to Build a Healthy, Sustainable Jazz Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sonoma-Marin Fair Announces 2019 Concert Series Loverboy, Sammy Kershaw, Aaron Tippin, Collin Raye, Lifehouse, and David Lee Murphy!

Contact: Christy Gentry [email protected] (707) 326-5058 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Artist Photos: https://goo.gl/B3Q2UY Sonoma-Marin Fair Announces 2019 Concert Series Loverboy, Sammy Kershaw, Aaron Tippin, Collin Raye, Lifehouse, and David Lee Murphy! PETALUMA, CA – March 8, 2019 – For eighty years the Sonoma-Marin Fair has been rocking Petaluma with its summer concert series and this year’s line-up of award-winning artists is the perfect group for the big celebration. Join fellow fairgoers for everything from throwback hits to collaborative jams from June 19-23 on the Petaluma Stage each night at 8 p.m. This year’s artists include Loverboy, Sammy Kershaw, Aaron Tippin, Collin Raye, Lifehouse, and David Lee Murphy. Hitting the Petaluma Stage on opening night is award-winning Loverboy ready to rock the crowd on Wednesday, June 19. With their trademark red leather pants, bandannas, big rock sound and high-energy live shows, Loverboy has sold more than 10 million albums, earning four multi-platinum plaques, including the four-million-selling “Get Lucky”, and a trio of double-platinum releases in their self-titled 1980 debut, “Keep It Up” and “Lovin’ Every Minute of It.” Their string of hits includes, in addition to the anthem “Working for the Weekend,” arena rock staples as “Lovin’ Every Minute of It,” “This Could Be the Night,” “Hot Girls in Love,” “The Kid is Hot Tonite,” and “Turn Me Loose.” Loverboy still holds a record of six Juno awards and since 1992; the band has maintained a steady road presence. In March 2009, the group was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall Of Fame. -

Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67

Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 Marc Howard Medwin A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: David Garcia Allen Anderson Mark Katz Philip Vandermeer Stefan Litwin ©2008 Marc Howard Medwin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MARC MEDWIN: Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 (Under the direction of David F. Garcia). The music of John Coltrane’s last group—his 1965-67 quintet—has been misrepresented, ignored and reviled by critics, scholars and fans, primarily because it is a music built on a fundamental and very audible disunity that renders a new kind of structural unity. Many of those who study Coltrane’s music have thus far attempted to approach all elements in his last works comparatively, using harmonic and melodic models as is customary regarding more conventional jazz structures. This approach is incomplete and misleading, given the music’s conceptual underpinnings. The present study is meant to provide an analytical model with which listeners and scholars might come to terms with this music’s more radical elements. I use Coltrane’s own observations concerning his final music, Jonathan Kramer’s temporal perception theory, and Evan Parker’s perspectives on atomism and laminarity in mid 1960s British improvised music to analyze and contextualize the symbiotically related temporal disunity and resultant structural unity that typify Coltrane’s 1965-67 works. -

The Big Adventure Press

Get ready for The Big Adventure Would you step away from your everyday life for the chance to make your dreams come true? Twelve regular Australians will be Grid in the hope of unearthing a These 12 ordinary Aussies will be doing just that. They will walk into The golden key. Only one of those keys pushed to their limits as their skills, Big Adventure with a dream and one will unlock the million dollar prize. smarts, speed and stamina are of them will walk away a millionaire. tested. The challenges are unlike anything But achieving their dream will not be ever seen before and will take place They will have to embrace the easy. on the Sky Rig, a stadium suspended unknown and face their fears Seven’s new adventure series will over water. head on. There will be doubts, see 12 strangers compete in extreme disappointments and failure. Host Jason Dundas will be there conditions for the prize of a lifetime. for all the thrills and spills. “The aim But those who don’t give up on On a secret island in the South of the game is to dig up as many their dreams will be triumphant. Pacific, carved out of the jungle, sits golden keys as possible,” he says. One million dollars lies waiting… the Treasure Grid. Under one of the “The more keys you have, the greater which lucky person will dig their way squares, a life-changing prize lies your chance of unlocking the million to victory? buried – one million dollars. bucks. Our players will do whatever The Big Adventure is an original In every episode, contestants will it takes to earn the right to dig for a Seven production from the makers of earn the right to dig in the Treasure fortune.” My Kitchen Rules and House Rules. -

JAZZ FUNDAMENTALS Jazz Piano, Theory, and More

JAZZ FUNDAMENTALS Jazz Piano, Theory, and More Dr. JB Dyas 310-206-9501 • [email protected] 2 JB Dyas, PhD Dr. JB Dyas has been a leader in jazz education for the past two decades. Formerly the Executive Director of the Brubeck Institute, Dyas currently serves as Vice President for Education and Curriculum Development for the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz at UCLA in Los Angeles. He oversees the Institute’s education and outreach programs including Jazz In America: The National Jazz Curriculum (www.jazzinamerica.org), one of the most significant and wide-reaching jazz education programs in the world. Throughout his career, he has performed across the country, taught students at every level, directed large and small ensembles, developed and implemented new jazz curricula, and written for national music publications. He has served on the Smithsonian Institution’s Task Force for Jazz Education in America and has presented numerous jazz workshops, teacher-training seminars, and jazz "informances" around the globe with such renowned artists as Dave Brubeck and Herbie Hancock. A professional bassist, Dyas has appeared with Jamey Aebersold, David Baker, Jerry Bergonzi, Red Rodney, Ira Sullivan, and Bobby Watson, among others. He received his Master’s degree in Jazz Pedagogy from the University of Miami and PhD in Music Education from Indiana University, and is a recipient of the prestigious DownBeat Achievement Award for Jazz Education. 3 Jazz Fundamentals Text: Aebersold Play-Along Volume 54 (Maiden Voyage) Also Recommended: Jazz Piano Voicings for the Non-Pianist and Pocket Changes I. Chromatic Scale (all half steps) C C# D D# E F F# G G# A A# B C C Db D Eb E F Gb G Ab A Bb B C Whole Tone Scale (all whole steps) C D E F# G# A# C Db Eb F G A B Db ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________ II. -

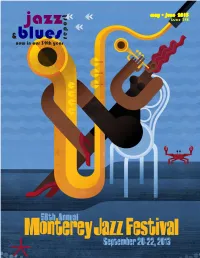

May • June 2013 Jazz Issue 348

may • june 2013 jazz Issue 348 &blues report now in our 39th year May • June 2013 • Issue 348 Lineup Announced for the 56th Annual Editor & Founder Bill Wahl Monterey Jazz Festival, September 20-22 Headliners Include Diana Krall, Wayne Shorter, Bobby McFerrin, Bob James Layout & Design Bill Wahl & David Sanborn, George Benson, Dave Holland’s PRISM, Orquesta Buena Operations Jim Martin Vista Social Club, Joe Lovano & Dave Douglas: Sound Prints; Clayton- Hamilton Jazz Orchestra, Gregory Porter, and Many More Pilar Martin Contributors Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, Dewey Monterey, CA - Monterey Jazz Forward, Nancy Ann Lee, Peanuts, Festival has announced the star- Wanda Simpson, Mark Smith, Duane studded line up for its 56th annual Verh, Emily Wahl and Ron Wein- Monterey Jazz Festival to be held stock. September 20–22 at the Monterey Fairgrounds. Arena and Grounds Check out our constantly updated Package Tickets go on sale on to the website. Now you can search for general public on May 21. Single Day CD Reviews by artists, titles, record tickets will go on sale July 8. labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 2013’s GRAMMY Award-winning years of reviews are up and we’ll be lineup includes Arena headliners going all the way back to 1974. Diana Krall; Wayne Shorter Quartet; Bobby McFerrin; Bob James & Da- Comments...billwahl@ jazz-blues.com vid Sanborn featuring Steve Gadd Web www.jazz-blues.com & James Genus; Dave Holland’s Copyright © 2013 Jazz & Blues Report PRISM featuring Kevin Eubanks, Craig Taborn & Eric Harland; Joe No portion of this publication may be re- Lovano & Dave Douglas Quintet: Wayne Shorter produced without written permission from Sound Prints; George Benson; The the publisher. -

A Search and Retrieval Based Approach to Music Score Metadata Analysis

A Search and Retrieval Based Approach to Music Score Metadata Analysis Jamie Gabriel FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY SYDNEY A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2018 CERTIFICATE OF ORIGINAL AUTHORSHIP I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as part of the collaborative doctoral degree and/or fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. This research is supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program. Production Note: Signature: Signature removed prior to publication. _________________________________________ Date: 1/10/2018 _________________________________________ i ACKNOWLEGEMENT Undertaking a dissertation that spans such different disciplines has been a hugely challenging endeavour, but I have had the great fortune of meeting some amazing people along the way, who have been so generous with their time and expertise. Thanks especially to Arun Neelakandan and Tony Demitriou for spending hours talking software and web application architecture. Also, thanks to Professor Dominic Verity for his deep insights on mathematics and computer science and helping me understand how to think about this topic in new ways, and to Professor Kelsie Dadd for providing me with some amazing opportunities over the last decade. -

TRISHA BROWN DANCE COMPANY Ili Trilogy

THÉÂTRE DES CHAMPS-ÉLYSÉES TRISHA BROWN DANCE COMPANY iLI Trilogy Trisha Brown, chorégraphie Dave Douglas, musique 16 au 19 novembre 2000 Document de communication du Festival d'Automne à Paris - tous droits réservés Trisha Brown Dance Company EL TRILOGY Five Part Weather Invention Rupture to Leon James Groove and Countermove Trisha Brown, chorégraphie Dave Douglas, musique Terry Winters, décors et costumes Jennifer Tipton, lumières Jeudi 16, vendredi 17, samedi 18, dimanche 19 novembre 2000, 20h dimanche 19 novembre 2000, 15h 5 représentations Service de presse - Nathalie Sergent Tél :01 49 52 50 70 - Fax :01 49 52 07 41 e-mail : [email protected] Document de communication du Festival d'Automne à Paris - tous droits réservés El Trilogy Depuis le début des années 1970 et la création de sa compagnie, Trisha Brown n'a cessé d'influencer le ballet contemporain, proposant un vocabu- Renseignements pratiquesp. 4 laire chorégraphique réinventé à chaque uvre. Ces dernières années, elle a entamé un cycle illustrant les relations de la danse et de la musique. Inaugu- Five Part Weather Inventionp. 5 rées par une pièce sur L'Offlande musicale de Bach, ses recherches se sont Rupture to Leon Jamesp. 6 Groove and Countermovep. 7 poursuivies avec les quatuors à cordes de Webern puis avec sa magnifique mise en scène de L'Orfeo de Monteverdi (créée à la Monnaie de Bruxelles au Trisha Brown, à propos d'El Trilogyp. 8 printemps 1998 et présentée par la suite entre autres au festival d'Aix-en- El Jubilation Trilogy, par Denise Luccionip. 10 Provence et au Théâtre des Champs-Élysées). -

June 2018 New Releases

June 2018 New Releases what’s PAGE inside featured exclusives 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately! 76 Vinyl Audio 3 CD Audio 15 FEATURED RELEASES HANK WILLIAMS - CLANNAD - TURAS 1980: PIG - THE LONESOME SOUND 2LP GATEFOLD RISEN Music Video DVD & Blu-ray 50 Non-Music Video DVD & Blu-ray 52 Order Form 84 Deletions and Price Changes 82 PORTLANDIA: CHINA SALESMAN THE COMPLETE SARTANA 800.888.0486 SEASON 8 [LIMITED EDITION 5-DISC BLU-RAY] 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 HANK WILLIAMS - SON HOUSE - FALL - LEVITATE: www.MVDb2b.com THE LONESOME SOUND LIVE AT OBERLIN COLLEGE, LIMITED EDITION TRIPLE VINYL APRIL 15, 1965 A Van Damme good month! MVD knuckles down in June with the Action classic film LIONHEART, starring Jean-Claude Van Damme. This combo DVD/Blu-ray gets its well-deserved deluxe treatment from our MVD REWIND COLLECTION. This 1991 film is polished with high-def transfers, behind-the- scenes footage, a mini-poster, interviews, commentaries and more. Coupled with the February deluxe combo pack of Van Damme’s BLACK EAGLE, why, it’s an action-packed double shot! Let Van Damme knock you out all over again! Also from MVD REWIND this month is the ABOMINABLE combo DVD/Blu-ray pack. A fully-loaded deluxe edition that puts Bigfoot right in your living room! PORTLANDIA, the IFC Network sketch comedy starring Fred Armisen and Carrie Brownstein is Ore-Gone with its final season, PORTLANDIA: SEASON 8. The irreverent jab at the hip and eccentric culture of Portland, Oregon has appropriately ended with Season 8, a number that has no beginning and no end. -

Michael Fires Off `Cop' Hit Investment," Adds Lippman

MENT Michael Fires Off `Cop' Hit investment," adds Lippman. "He's head. He's a fan of Eddie Murphy, CONE TO ONE J BY STEVE GEIT one of its major artists, and it's ob- so we played it for [film producers] NEW YORK With radio stations viously concerned to make sure his Don Simpson and Jerry Bruck - Richard Branson already playing George Michael's "I records go out to radio and that his heimer and they loved it." Want Your Sex" off the MCA image is out there. CBS was kind Of the potential dangers of being discusses Virgin's soundtrack "Beverly Hills Cop II," enough to allow us to put the song associated with a movie, Lippman Columbia's promotional staff rush - on the MCA soundtrack, but we says, "The biggest possible minus is renewed venture released the single last week. were always concerned that it had that the movie isn't well received, into the U.S. Sources say Columbia was forced the rights to the single." and therefore people don't take the to switch gears after MCA serviced According to Lippman, "I Want music seriously. In this case, we advance copies of the soundtrack Your Sex" provides an "excellent saw the movie, thought it was Richard Branson, head of the dous feather in the cap for every- two weeks ahead of its May 18 com- opportunity" to keep Michael in the great, and knew it would be a block- ever -expanding Virgin empire, body here that he decided to leave mercial release. MCA was eager to public's eye while he completes his buster. -

Oshkosh Waterfest in August

TO THE MUSIC MUSIC MOVES OUTDOORS 10+ SUMMER FESTIVALS Get Out & Do What You Like to do JUNE 2018 Colin Mochre Warming up to Wisconsin weather by default LOVERBOY Reliably rocking Oshkosh Waterfest in August FOX CITIES PAC Music for all this fall UPcomiNG EVENts: PLUS! Fox Cities | Green Bay MARK’S Marshfield | Oshkosh Stevens Point | Waupaca EAST SIDE NO Detail too small Wausau | Wisconsin Rapids FOR success Waterfest Tickets Celebrates on sale now Summer C l i c k h e r e BY ROCKING THE FOX Advance Ticket Availability Also appearing VIP & General Admission Season Passes The Producers Thomas Wynn & Copper Box (On Line, Oshkosh Chamber & Bank First) Single Event VIP Admission Paul Sanchez and The Believers The Legendary (On Line, Oshkosh Chamber, Bank First) The Rolling Road Show Davis Rogan Band Shadows of Knight Single Event General Admission (On Line-only) The Tin Men REMO DRIVE Brett Newski & No Tomorrow Admissions are also available at the gate day of show Questions: Call Oshkosh Chamber (920) 303-2265 Alex McMurray Road Trip The Pocket Kings For Group Discounts, Gazebo & Stage Right admissions The Lao Tizer Quartet Nick Schnebelen And more! Sponsorships: Mike at (920) 279-7574 or John at (920) 303-2265 x18 WATERFEST.ORG FOR MORE INFO Get Out & Do What You Like to Do JUNE 2018 p.12 COLIN MOCHRE PROFESSES HE HAS NO PLANS P. 4 P. 8 P.18 P.28 DEPARTMENTS LOWDOWN LOVERBOY MUSIC FEsts FALL FOX PUBLISHER’S NOTE p. 2 BRASS Still lovin’ every 11 Wisconsin CITIES PAC A little of everything minute of summer festivals Musical variety SUPPER CLUB - musical in Milwaukee working for the on sale now Mark’s East Side weekend in Appleton p.24 EVENts CALENdaR p.34 PUBLISHER’S NOTE Move It Outdoors JuneFa mily2018, Fu Vol.n Edit2, Issueion 6 June is here and it is time to get Supper Club Guy- David Brierely PUBLISHERS NORMA JEAN FOCHS outside and enjoy some warm goes German at Mark’s East Side PATRICK BOYLE weather and sunshine. -

2007 Newsletter

merican rass uintet A FORTFORTY-EIGHTHY-EIGHTHB QSEASONS EASON Volume 16, Number 1 New York, January 2008 N ew sletter Juilliard Residency at 20 By Raymond Mase Rojak on the Road - 2007 This fall the American Brass By John Rojak Quintet quietly reached anoth - It must have been a dream. Through the haze of my er milestone in our nearly sleep-filled eyes, I heard, then saw the two cleaning women half-century history—that conducting their morning conversation at thirty paces. Could being the 20th anniversary we really be sleeping on airport chairs at Gate D6 in Dulles International Airport? Had we really missed our connection merican of our residency at The A Juilliard School. Over these and been unable to find a single room within 30 miles? (And rass uintet two decades, the was this the best way to be celebrating my birthday?!) B Q Last season started in spectacular fashion but we FORTY-EIGHTH SEASON ABQ/Juilliard collaboration has not only introduced many should have known that our good travel fortunes would mutate young players to the challenges into trials of patience and endurance. There were lessons that 1960-2008 and rewards of brass chamber we learned from our travails, so this season we decided to music and helped them refine those specific skills, but has make some long drives to avoid connecting flights and mis - also had a remarkable impact on the presence of brass cham - placed baggage. And on these drives we'll have a chance to ber music in New York. get our business meetings taken care of, unless the Yankees An ABQ residency wasn’t a new idea when Bob are on the radio. -

Los Angeles Master Chorale Celebrates the 20Th Anniversary Of

PRESS RELEASE Media Contact: Jennifer Scott [email protected] | 213-972-3142 LOS ANGELES MASTER CHORALE CELEBRATES 20TH ANNIVERSARY OF LUX AETERNA BY MORTEN LAURIDSEN & SHOWCASES LOS ANGELES COMPOSERS WITH CONCERTS & GALA JUNE 17-22 Clockwise, l-r: Composers Eric Whitacre, Morten Lauridsen, Shawn Kirchner, Moira Smiley, Billy Childs, & Esa-Pekka Salonen. Concerts include world premieres by Billy Childs and Moira Smiley, a West Coast premiere by Eric Whitacre, and works by Shawn Kirchner and Esa-Pekka Salonen 1 3 5 N O R T H G R A N D AV E N U E , LO S A N G E L E S , C A L I F O R N I A 9 0 0 1 2 - -- 3 0 1 3 2 1 3 - 9 7 2 - 3 1 2 2 | L A M A ST E R C H O R A L E . O R G LUX AETERNA 20TH ANNIVERSARY, PAGE 2 First performances of Lux Aeterna with full orchestra in Walt Disney Concert Hall, conducted by Grant Gershon Gala to honor Morten Lauridsen on Sunday, June 18 Saturday, June 17 – 2 PM Matinee Concert Sunday, June 18 – 6 PM Concert, Gala, & Lux Onstage Party Thursday, June 22 – 8 PM “Choir Night” Concert & Group Sing CONCERT TICKETS START AT $29 LAMASTERCHORALE.ORG | 213-972-7282 (Los Angeles, CA) May 31, 2017 – The Los Angeles Master Chorale brings works by six Los Angeles composers together on a concert program celebrating the 20th anniversary of Morten Lauridsen’s choral masterwork Lux Aeterna June 17-22 in Walt Disney Concert Hall.