New Entry of Record Labels in the Music Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

311 Creatures

311 Creatures (For A While) 10 Years After I'd Love To Change The World 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants 10,000 Maniacs Like The Weather 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are Days 10,000 Maniacs Trouble Me 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc The Things We Do For Love 112 Come See Me 112 Cupid 112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 112 Peaches & Cream 112Super Cat Na Na Na 1910 Fruitgum Co. 1 2 3 Red Light 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 2Pac California Love 2Pac Changes 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac How Do You Want It 2Pau Heart And Soul 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down Duck And Run 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Of Hearts Arizon Rain 311 All Mixed Up 311 Amber 311 Down 311 I'll Be Here Awhile 311 You Wouldn't Believe 38 Special Caught Up In You 38 Special Hold On Loosely 38 Special Rockin' Into The Night 38 Special Second Chance 38 Special Wild Eyed Southern Boys 3LW I Do 3LW No More Baby 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3rd Stroke No Light 4 Non Blondes What's Up 4 PM Sukiyaki 4 Runner Cain's Blood 4 Runner Ripples 4Him Basics Of Life 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 cent pimp 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Wanksta 5th Dimension Aquarius 5th Dimension Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 5th Dimension One Less Bell To Answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up And Away 5th Dimension Wedding Bell Blues 69 Boyz Tootie Roll 702 Get It Together 702 Steelo 702 Where My -

SKIVLISTA 3-2018 Hello Music Lovers, the Following Items Will Be Sold on Open Auction Which Means You Can Ask About Leading Bids by Phone Or Mail

AUCTION – AUKTION SKIVLISTA 3-2018 Hello music lovers, The following items will be sold on open auction which means you can ask about leading bids by phone or mail. Please send your starting bids by mail, phone or post before the last day of auction. Hoppas allt är bra med er och era skivspelare. Här kommer en ny lista och jag hoppas du hittar något intressant till Auction deadline is Tuesday, March 27, 2018 at 22.00 / 10 PM Central samlingen. Jag har reflekterat över att vissa artister som tidigare brukade vara mycket efterfrågade nu är tämligen European time (20.00 / 8 PM UTC/GMT) svårsålda. Två bra exempel är Elvis och Spotnicks. Visst, jag förstår att det är ointressant om man redan har alla STOPPDATUM ALLTSÅ TISDAGEN DEN 27 MARS 2018 KL. 22.00 SVENSK skivorna på listan i samlingen. Men då ser jag heller ingen anledning att aktivt leta efter skivor med dessa artister för SOMMARTID. att eventuellt hitta något ni saknar. Det bästa är om ni som bara vill ha Elvis eller någon annan artist skickar en lista på vad ni har eller vad ni söker. Jag hjälper gärna till att leta fram skivor ni saknar men att lägga ner tid och resurser 7" SINGLES/EPs FOR AUCTION på att köpa in speciella artister som ni ändå aldrig köper verkar knappast meningsfullt. Men kom gärna med förslag på vad ni vill se mer av i mina listor. Någon speciell musikgenre? Minimum bid (M.B.) is SEK 50 / US$ 8 / € 6,- / £ 5 unless otherwise noted . Rutan har fått en fettknöl på huvudet bortopererad i dag men är nu hemma igen, pigg och glad. -

The Big Adventure Press

Get ready for The Big Adventure Would you step away from your everyday life for the chance to make your dreams come true? Twelve regular Australians will be Grid in the hope of unearthing a These 12 ordinary Aussies will be doing just that. They will walk into The golden key. Only one of those keys pushed to their limits as their skills, Big Adventure with a dream and one will unlock the million dollar prize. smarts, speed and stamina are of them will walk away a millionaire. tested. The challenges are unlike anything But achieving their dream will not be ever seen before and will take place They will have to embrace the easy. on the Sky Rig, a stadium suspended unknown and face their fears Seven’s new adventure series will over water. head on. There will be doubts, see 12 strangers compete in extreme disappointments and failure. Host Jason Dundas will be there conditions for the prize of a lifetime. for all the thrills and spills. “The aim But those who don’t give up on On a secret island in the South of the game is to dig up as many their dreams will be triumphant. Pacific, carved out of the jungle, sits golden keys as possible,” he says. One million dollars lies waiting… the Treasure Grid. Under one of the “The more keys you have, the greater which lucky person will dig their way squares, a life-changing prize lies your chance of unlocking the million to victory? buried – one million dollars. bucks. Our players will do whatever The Big Adventure is an original In every episode, contestants will it takes to earn the right to dig for a Seven production from the makers of earn the right to dig in the Treasure fortune.” My Kitchen Rules and House Rules. -

Visions for Intercultural Music Teacher Education Landscapes: the Arts, Aesthetics, and Education

Landscapes: the Arts, Aesthetics, and Education Heidi Westerlund Sidsel Karlsen Heidi Partti Editors Visions for Intercultural Music Teacher Education Landscapes: the Arts, Aesthetics, and Education Volume 26 Series Editor Liora Bresler, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, USA Editorial Board Judith Davidson, University of Massachusetts, Lowell, USA Magne Espeland, Stord University, Stord, Norway Chris Higgins, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, USA Helene Illeris, University of Adger, Kristiansand S, Norway Mei-Chun Lin, National University of Tainan, Tainan City, Taiwan Donal O’Donoghue, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada Mike Parsons, The Ohio State University, Columbus, USA Eva Sæther, Malmö Academy of Music, Lund University, Malmö, Sweden Shifra Schonmann, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel Susan W. Stinson, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Greensboro, USA Scope This series aims to provide conceptual and empirical research in arts education, (including music, visual arts, drama, dance, media, and poetry), in a variety of areas related to the post-modern paradigm shift. The changing cultural, historical, and political contexts of arts education are recognized to be central to learning, experience, knowledge. The books in this series presents theories and methodological approaches used in arts education research as well as related disciplines—including philosophy, sociology, anthropology and psychology of arts education. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/6199 -

Iikbillboard

CANADA (Courtesy The Record) As of 6/13/85 AUSTRALIA (Courtesy Kent Music Report) As of 6/17/85 lir SINGLES 1 5 SINGLESUSSUDIO PHIL COLLINS ATLANTIC /WEA 1 1 WOULD I LIE TO YOU EURYTHMICS RCA 2 1 EVERYBODY WANTS TO RULE THE WORLD TEARS FOR FEARS 2 7 ANGEL MADONNA SIRE VERTIGO/POLYGRAM 3 3 WE ARE THE WORLD USA FOR AFRICA CBS 3 2 DON'T YOU (FORGET ABOUT ME) SIMPLE MINDS VIRGIN / POLYGRAM 4 9 50 YEARS UNCANNY X -MEN MUSHRO OM 4 3 NIGHT DEBARGE GORDY /QUALITY RHYTHM OF THE 5 17 LIVE IT UP MENTAL AS ANYTHING REGULAR 5 6 COLUMBIA /CBS EVERYTHING SHE WANTS WHAM! 6 5 RHYTHM OF THE NIGHT DEBARGE ORDr 6 11 WOULD I RCA - LIE TO YOU EURYTHMICS 7 6 DON'T YOU (FORGET ABOUT ME) SIMPLE MINDS VIRGIN NEW 7 NEVER SURRENDER COREY HART AQUARIUS /CAPITOL 8 4 EVERYBODY WANTS TO RULE THE WORLD TEARS FOR FEARS 8 17 BLACK CARS GINO VANNELLI POLYDOR/POLYGRAM MERCURY 9 12 A VIEW TO A KILL DURAN DURAN CAPITOL 9 8 WE CLOSE OUR EYES GO WEST CHRYSALIS 10 7 WALKING ON SUNSHINE KATRINA & THE WAVES ATTIC /A &M 10 10 19 PAUL HARDCASTLE CHRYSALIS 11 4 CRAZY FOR YOU MADONNA SIRE /WEA 11 2 CAN'T FIGHT THIS FEELING REO SPEEDWAGON EPIC 12 8 SMOOTH OPERATOR SADE PORTRAIT /CBS 12 NEW WALKING ON SUNSHINE KATRINA &WAVES CAPITOL 13 15 AXEL F HAROLD FALTERMEYER MCA 13 NEW A VIEW TO A KILL DURAN DURAN EMI 14 13 OBSESSION ANIMOTION MERCURY / POLYGRAM 14 18 WE WILL TOGETHER EUROGLIDERS CBS 15 NEW RASPBERRY BERET PRINCE & THE REVOLUTION PAISLEY PARK /WEA 15 14 WIDE BOY NIK KERSHAW MCA 16 16 HEAVEN BRYAN ADAMS A &M 16 12 NIGHTSHIFT COMMODORES MOTOWN 17 10 TEARS ARE NOT ENOUGH NORTHERN LIGHTS COLUMBIA /CBS 17 13 JUST A GIGOLO DAVID LEE ROTH WARNER 18 14 WE ARE THE WORLD USA FOR AFRICA COLUMBIA /CBS 18 11 THE HEAT IS ON GLENN FREY MCA 19 18 TOKYO ROSE IDLE EYES WEA 19 15 ONE MORE NIGHT PHIL COLLINS WEA Wi's: POWER STATION PARLOPHONE 20 20 THINGS CAN ONLY GET BETTER HOWARD JONES WEA 20 16 SOME LIKE IT HOT %..Copyright 1985, Billboard Publications, Inc. -

June 2018 New Releases

June 2018 New Releases what’s PAGE inside featured exclusives 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately! 76 Vinyl Audio 3 CD Audio 15 FEATURED RELEASES HANK WILLIAMS - CLANNAD - TURAS 1980: PIG - THE LONESOME SOUND 2LP GATEFOLD RISEN Music Video DVD & Blu-ray 50 Non-Music Video DVD & Blu-ray 52 Order Form 84 Deletions and Price Changes 82 PORTLANDIA: CHINA SALESMAN THE COMPLETE SARTANA 800.888.0486 SEASON 8 [LIMITED EDITION 5-DISC BLU-RAY] 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 HANK WILLIAMS - SON HOUSE - FALL - LEVITATE: www.MVDb2b.com THE LONESOME SOUND LIVE AT OBERLIN COLLEGE, LIMITED EDITION TRIPLE VINYL APRIL 15, 1965 A Van Damme good month! MVD knuckles down in June with the Action classic film LIONHEART, starring Jean-Claude Van Damme. This combo DVD/Blu-ray gets its well-deserved deluxe treatment from our MVD REWIND COLLECTION. This 1991 film is polished with high-def transfers, behind-the- scenes footage, a mini-poster, interviews, commentaries and more. Coupled with the February deluxe combo pack of Van Damme’s BLACK EAGLE, why, it’s an action-packed double shot! Let Van Damme knock you out all over again! Also from MVD REWIND this month is the ABOMINABLE combo DVD/Blu-ray pack. A fully-loaded deluxe edition that puts Bigfoot right in your living room! PORTLANDIA, the IFC Network sketch comedy starring Fred Armisen and Carrie Brownstein is Ore-Gone with its final season, PORTLANDIA: SEASON 8. The irreverent jab at the hip and eccentric culture of Portland, Oregon has appropriately ended with Season 8, a number that has no beginning and no end. -

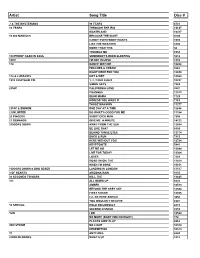

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Lister); an American Folk Rhapsody Deutschmeister Kapelle/JULIUS HERRMANN; Band of the Welsh Guards/Cap

Guild GmbH Guild -Light Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - e-mail: [email protected] CD-No. Title Track/Composer Artists GLCD 5101 An Introduction Gateway To The West (Farnon); Going For A Ride (Torch); With A Song In My Heart QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT FARNON; SIDNEY TORCH AND (Rodgers, Hart); Heykens' Serenade (Heykens, arr. Goodwin); Martinique (Warren); HIS ORCHESTRA; ANDRE KOSTELANETZ & HIS ORCHESTRA; RON GOODWIN Skyscraper Fantasy (Phillips); Dance Of The Spanish Onion (Rose); Out Of This & HIS ORCHESTRA; RAY MARTIN & HIS ORCHESTRA; CHARLES WILLIAMS & World - theme from the film (Arlen, Mercer); Paris To Piccadilly (Busby, Hurran); HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; DAVID ROSE & HIS ORCHESTRA; MANTOVANI & Festive Days (Ancliffe); Ha'penny Breeze - theme from the film (Green); Tropical HIS ORCHESTRA; L'ORCHESTRE DEVEREAUX/GEORGES DEVEREAUX; (Gould); Puffin' Billy (White); First Rhapsody (Melachrino); Fantasie Impromptu in C LONDON PROMENADE ORCHESTRA/ WALTER COLLINS; PHILIP GREEN & HIS Sharp Minor (Chopin, arr. Farnon); London Bridge March (Coates); Mock Turtles ORCHESTRA; MORTON GOULD & HIS ORCHESTRA; DANISH STATE RADIO (Morley); To A Wild Rose (MacDowell, arr. Peter Yorke); Plink, Plank, Plunk! ORCHESTRA/HUBERT CLIFFORD; MELACHRINO ORCHESTRA/GEORGE (Anderson); Jamaican Rhumba (Benjamin, arr. Percy Faith); Vision in Velvet MELACHRINO; KINGSWAY SO/CAMARATA; NEW LIGHT SYMPHONY (Duncan); Grand Canyon (van der Linden); Dancing Princess (Hart, Layman, arr. ORCHESTRA/JOSEPH LEWIS; QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT Young); Dainty Lady (Peter); Bandstand ('Frescoes' Suite) (Haydn Wood) FARNON; PETER YORKE & HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; LEROY ANDERSON & HIS 'POPS' CONCERT ORCHESTRA; PERCY FAITH & HIS ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/JACK LEON; DOLF VAN DER LINDEN & HIS METROPOLE ORCHESTRA; FRANK CHACKSFIELD & HIS ORCHESTRA; REGINALD KING & HIS LIGHT ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/SERGE KRISH GLCD 5102 1940's Music In The Air (Lloyd, arr. -

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

Sorted by ARTIST * * * * Please Note That The

* * * * Sorted by ARTIST * * * * Please note that the artist could be listed by FIRST NAME, or preceded by 'THE' or 'A' Title Artist YEAR ----------------------------------------- ------------------------ ----- 7764 BURN BREAK CRASH 'ANYSA X SNAKEHIPS 2017 2410 VOICES CARRY 'TIL TUESDAY 1985 2802 GET READY 4 THIS 2 UNLIMITED 1995 9144 MOOD 24KGOLDN 2021 8180 WORRY ABOUT YOU 2AM CLUB 2010 2219 BE LIKE THAT 3 DOORS DOWN 2001 6620 HERE WITHOUT YOU 3 DOORS DOWN 2003 1517 KRYPTONITE 3 DOORS DOWN 2000 5216 LET ME GO 3 DOORS DOWN 2005 0914 HOLD ON LOOSELY 38 SPECIAL 1981 8115 DON'T TRUST ME 3OH!3 2009 8214 MY FIRST KISS 3OH!3/ KE$HA 2010 7336 AMNESIA 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER 2014 8710 EASIER 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER 2019 7312 SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER 2014 8581 WANT YOU BACK 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER 2018 8611 YOUNGBLOOD 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER 2018 7413 IN DA CLUB 50 CENT 2004 8758 ALL MY FRIENDS ARE FAKE 58TE McRAE 2020 2805 TOOTSIE ROLL 69 BOYZ 1995 8776 SAY SO 71JA CAT 2020 7318 ALREADY HOME A GREAT BIG WORLD 2014 7117 THIS IS THE NEW YEAR A GREAT BIG WORLD 2013 3109 BACK AND FORTH AALIYAH 1994 4809 MORE THAN A WOMAN AALIYAH 2002 1410 TRY AGAIN AALIYAH 2000 7744 FOOL'S GOLD AARON CARTER 2016 2112 I MISS YOU AARON HALL 1994 2903 DANCING QUEEN ABBA 1977 6157 THE LOOK OF LOVE (PART ONE) ABC 1982 8542 ODYSSEY ACCIDENTALS 2017 8154 WHATAYA WANT FROM ME ADAM LAMBERT 2010 8274 ROLLING IN THE DEEP ADELE 2011 8369 SOMEONE LIKE YOU ADELE 2012 5964 BACK IN THE SADDLE AEROSMITH 1977 5961 DREAM ON AEROSMITH 1973 5417 JADED AEROSMITH 2001 5962 SWEET EMOTION AEROSMITH 1975 5963 WALK THIS WAY AEROSMITH 1976 8162 RELEASE ME AGNES 2010 9132 BANG! AJR 2020 6906 I WANNA LOVE YOU AKON FEAT SNOOP DOGG 2007 7810 LOCKED UP AKON feat STYLES P. -

Radio Essentials 2012

Artist Song Series Issue Track 44 When Your Heart Stops BeatingHitz Radio Issue 81 14 112 Dance With Me Hitz Radio Issue 19 12 112 Peaches & Cream Hitz Radio Issue 13 11 311 Don't Tread On Me Hitz Radio Issue 64 8 311 Love Song Hitz Radio Issue 48 5 - Happy Birthday To You Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 21 - Wedding Processional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 22 - Wedding Recessional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 23 10 Years Beautiful Hitz Radio Issue 99 6 10 Years Burnout Modern Rock RadioJul-18 10 10 Years Wasteland Hitz Radio Issue 68 4 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night Radio Essential IssueSeries 44 Disc 44 4 1975, The Chocolate Modern Rock RadioDec-13 12 1975, The Girls Mainstream RadioNov-14 8 1975, The Give Yourself A Try Modern Rock RadioSep-18 20 1975, The Love It If We Made It Modern Rock RadioJan-19 16 1975, The Love Me Modern Rock RadioJan-16 10 1975, The Sex Modern Rock RadioMar-14 18 1975, The Somebody Else Modern Rock RadioOct-16 21 1975, The The City Modern Rock RadioFeb-14 12 1975, The The Sound Modern Rock RadioJun-16 10 2 Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 4 2 Pistols She Got It Hitz Radio Issue 96 16 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This Radio Essential IssueSeries 23 Disc 23 3 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 16 21 Savage Feat. J. Cole a lot Mainstream RadioMay-19 11 3 Deep Can't Get Over You Hitz Radio Issue 16 6 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun Hitz Radio Issue 46 6 3 Doors Down Be Like That Hitz Radio Issue 16 2 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes Hitz Radio Issue 62 16 3 Doors Down Duck And Run Hitz Radio Issue 12 15 3 Doors Down Here Without You Hitz Radio Issue 41 14 3 Doors Down In The Dark Modern Rock RadioMar-16 10 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time Hitz Radio Issue 95 3 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Hitz Radio Issue 3 9 3 Doors Down Let Me Go Hitz Radio Issue 57 15 3 Doors Down One Light Modern Rock RadioJan-13 6 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone Hitz Radio Issue 31 2 3 Doors Down Feat. -

PAOLO FRESU Discografia Completa

PAOLO FRESU Discografia completa * * * Roberto Ottaviano Aspects Tactus 1983 (Ita) Paolo Damiani/Gianluigi Trovesi Quintet Roccellanea Ismez 1983 (Ita) Paolo Damiani Opus Music ensemble Flash Back Ismez 1983 (Ita) Paolo Fresu Quintet Ostinato Splasc(h) 1985 (Ita) Wheeler/Fresu/Taylor/Oxley/Wistone/Damiani Live in Roccella Jonica Ismez 1985 (Ita) Musica Mu(n)ta Orchestra Anninnia Ismez 1985 (Ita) Piero Marras In Concerto Tekno 1985 (Ita) Giovanni Tommaso Quintet Via G.T. Red Record 1986 (Ita) Paolo Fresu Quintet feat David Liebman Inner Voices Splasc(h) 1986 (Ita) Mimmo Cafiero Emersion Ismj 1986 (Ita) Cosmo Intini Jazz Set See in the Cosmic Splasc(h) 1986 (Ita) Barga jazz Orchestra 1986 Barga jazz 1986 (Ita) Max Nightime Call Solid Air 1986 (Ita) Attilio Zanchi Early Spring Splasc(h) 1987 (Ita) Paolo Fresu Quintet Mamût Splasc(h) 1987 (Ita) Barga jazz Orchestra 1987 Splasc(h) 1988 (Ita) Mimmo Cafiero I Go Splasc(h) 1988 (Ita) Paolo Damiani Quintet Pour Memory Splasc(h) 1988 (Ita) Billy’s Garage Billy’s Garage Jazz Sardegna 1988 (Ita) Aldo Romano Ritual OWL 1988 (Fra) Giovanni Tommaso Quintet To Chet Red Record 1988 (Ita) Paolo Fresu Quintet Qvarto Splasc(h) 1988 (Ita) Roberto Cipelli Moona Moore Splasc(h) 1989 (Ita) Big Bang Orchestra con Phil Woods Embraceable you Philology 1989 (Ita) Tiziano Popoli Lezioni di anatomia Stile libero 1989 (Ita) Paolo Fresu/Furio Di Castri/Francesco Tattara Opale Phrases 1989 (Ita) Paolo Marrocco Grosso modo Stile libero 1989 (Ita) Alice Il sole nella pioggia EMI 1989 (Ita) (#) Artisti vari (Paolo Fresu