Wherethere.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record—Senate S4700

S4700 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE August 2, 2017 required. American workers have wait- of Kansas, to be a Member of the Na- billion each year in State and local ed too long for our country to crack tional Labor Relations Board for the taxes. down on abusive trade practices that term of five years expiring August 27, As I said at the beginning, I have had rob our country of millions of good- 2020. many differences with President paying jobs. The PRESIDING OFFICER. Under Trump, particularly on the issue of im- Today, I am proud to announce that the previous order, the time until 11 migration in some of the speeches and the Democratic Party will be laying a.m. will be equally divided between statements he has made, but I do ap- out our new policy on trade, which in- the two leaders or their designees. preciate—personally appreciate—that cludes, among other things, an inde- The assistant Democratic leader. this President has kept the DACA Pro- pendent trade prosecutor to combat DACA gram in place. trade cheating, not one of these endless Mr. DURBIN. Mr. President, many I have spoken directly to President WTO processes that China takes advan- times over the last 6 months, I have Trump only two times—three times, tage of over and over again; a new come to the Senate to speak out on perhaps. The first two times—one on American jobs security council that issues and to disagree with President Inauguration Day—I thanked him for will be able to review and stop foreign Trump. -

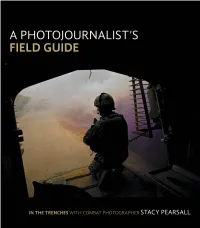

A Photojournalist's Field Guide: in the Trenches with Combat Photographer

A PHOTOJOURNALISt’S FIELD GUIDE IN THE TRENCHES WITH COMBAT PHOTOGRAPHER STACY PEARSALL A Photojournalist’s Field Guide: In the trenches with combat photographer Stacy Pearsall Stacy Pearsall Peachpit Press www.peachpit.com To report errors, please send a note to [email protected] Peachpit Press is a division of Pearson Education. Copyright © 2013 by Stacy Pearsall Project Editor: Valerie Witte Production Editor: Katerina Malone Copyeditor: Liz Welch Proofreader: Erin Heath Composition: WolfsonDesign Indexer: Valerie Haynes Perry Cover Photo: Stacy Pearsall Cover and Interior Design: Mimi Heft Notice of Rights All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or trans- mitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy- ing, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For information on getting permission for reprints and excerpts, contact [email protected]. Notice of Liability The information in this book is distributed on an “As Is” basis, without warranty. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of the book, neither the author nor Peachpit shall have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the instructions contained in this book or by the computer software and hardware products described in it. Trademarks Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and Peachpit was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations appear as requested by the owner of the trademark. -

70Th Annual 1St Cavalry Division Association Reunion

1st Cavalry Division Association 302 N. Main St. Non-Profit Organization Copperas Cove, Texas 76522-1703 US. Postage PAID West, TX Change Service Requested 76691 Permit No. 39 PublishedSABER By and For the Veterans of the Famous 1st Cavalry Division VOLUME 66 NUMBER 1 Website: http://www.1cda.org JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2017 The President’s Corner Horse Detachment by CPT Jeremy A. Woodard Scott B. Smith This will be my last Horse Detachment to Represent First Team in Inauguration Parade By Sgt. 833 State Highway11 President’s Corner. It is with Carolyn Hart, 1st Cav. Div. Public Affairs, Fort Hood, Texas. Laramie, WY 82070-9721 deep humility and considerable A long standing tradition is being (307) 742-3504 upheld as the 1st Cavalry Division <[email protected]> sorrow that I must announce my resignation as the President Horse Cavalry Detachment gears up to participate in the Inauguration of the 1st Cavalry Division Association effective Saturday, 25 February 2017. Day parade Jan. 20 in Washington, I must say, first of all, that I have enjoyed my association with all of you over D.C. This will be the detachment’s the years…at Reunions, at Chapter meetings, at coffees, at casual b.s. sessions, fifth time participating in the event. and at various activities. My assignments to the 1st Cavalry Division itself and “It’s a tremendous honor to be able my friendships with you have been some of the highpoints of my life. to do this,” Capt. Jeremy Woodard, To my regret, my medical/physical condition precludes me from travelling. -

Order of Battle Changes for Operation Phantom Thunder

BACKGROUNDER #2 Order of Battle for Operation Phantom Thunder Kimberly Kagan, Executive Director and Wesley Morgan, Researcher June 20, 2007 General David Petraeus, commander of Multi-National Forces-Iraq, and Lieutenant General Raymond Odierno, commander of Multi-National Corps-Iraq, launched a coordinated offensive operation on June 15, 2007 to clear al Qaeda strongholds outside of Baghdad. The arrival of the fifth Army “surge” brigade, the Marine Expeditionary Unit, and the combat aviation brigade enabled GEN Petraeus and LTG Odierno to begin this major offensive, named “Operation Phantom Thunder.” Three different U.S. Division Headquarters in different provinces are participating in Phantom Thunder. Multi-National Division-North (Diyala); Multi-National Division-Center (North Babil and Baghdad); and Multi-National Division-West (Anbar). In addition to reinforcing these areas with new troops, LTG Odierno and his division commanders have repositioned some brigades and battalions that were already operating in and around Baghdad. MND-North, Diyala Operation Arrowhead Ripper The core unit in Diyala has been 3rd BCT (Brigade Combat Team), 1st Cavalry Division, which has four battalions plus reinforcements. One of its battalions, 1-12 CAV, has been stationed on FOB Warhorse. A second battalion from the same brigade, the 6-9 ARS, has been operating in Muqdadiya, northeast of Baquba. The 5-73 RSTA (Reconnaissance, Scouting, and Target Acquisition Squadron) has been operating in the river valley northeast of Baquba (in locations such as Zaganiyah). The 5-20 Infantry has been operating in and around southern Baquba. (In addition, MND-N has sent a company from 2-35 Infantry to 5-73 and a company from 1-505 Parachute Infantry Regiment to 6-9 in order to provide those battalions with infantry). -

19 Engineer Battalion United States Army

19TH ENGINEER BATTALION UNITED STATES ARMY SHIELD: The shield of the coat of arms is used to indicate the descent of the 19th Engineer Battalion from the 3rd Battalion of the 36th Engineer Regiment. COLORS: The colors red and white are used for Engineers. The wavy partition line and the Seahorse symbolize participation in Marine Transportation and Amphibious Landings by the 36th Engineer Regiment. MOTTO: ACUTUS ACUMEN (1952-1976) ACUTUM ACUMEN (1976-Present) Translation - “SHARP INGENUITY” DEDICATION: This documentation is a history of the soldiers and key events of the 19th Engineer Battalion. The men who served and even gave their lives for the preservation of American ideals are remembered within these pages. Were it not for the soldiers of the 19th Engineer Battalion, the victories chronicled herein could not have taken place. Therefore, in remembrance of the soldiers, let this document be proudly dedicated to the men of the 19th Engineer Battalion. INTRODUCTION: The heritage of the 19th Engineer Battalion is a long and proud one. Its parent unit, the 36th Engineer Combat Regiment was named by the Nazi’s as “The Little Seahorse Division”. During WORLD WAR II, the men of the Regiment gave their energy, hearts and lives for America from 1941 to 1945. They participated in the African campaign, and through the muddy and bloody Italian and French campaigns, across Germany and into Austria by the end of the war. While stationed in the States during the COLD WAR the Battalion participated in disaster relief from hurricanes and floods, trained, and were always ready for missions assigned. -

Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia -ad-Dawlah l الدولة السلمية :The Islamic State (IS); (Arabic ʾIslāmiyyah), formerly the Islamic State of Iraq and the Islamic State (Arabic) الدولة السلمية Dāʿish) or the داعش :Levant (ISIL /ˈaɪsəl/; Arabic acronym Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS /ˈaɪsɪs/),[a] is a Sunni ad-Dawlah l-ʾIslāmiyyah jihadist group in the Middle East. In its self-proclaimed status as a caliphate, it claims religious authority over all Muslims across the world,[65] and aspires to bring much of the Muslim- inhabited regions of the world under its political control[66] beginning with Iraq, Syria and other territories in the Levant region which include Jordan, Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, Flag Coat of arms Cyprus and part of southern Turkey.[67] It has been designated Motto: (Arabic) باقية وتتمدد as a foreign terrorist organization by the United States, the "Bāqiyah wa-Tatamaddad" (transliteration) United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, Indonesia and Saudi "Remaining and Expanding"[1][2] Arabia, and has been described by the United Nations[68] and Western and Middle Eastern media as a terrorist group. The United Nations and Amnesty International have accused the group of grave human rights abuses. ISIS is the successor to Tanzim Qaidat al-Jihad fi Bilad al- Rafidayn—later commonly known as Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI)—formed by Abu Musab Al Zarqawi in 1999, which took part in the Iraqi insurgency against American-led forces and their Iraqi allies following the 2003 invasion of Iraq.[67][69] During the 2003–2011 Iraq War, it joined other Sunni insurgent groups to form the Mujahideen Shura Council As of 4 September 2014 and consolidated further into the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI Areas controlled by the Islamic State [69][70] Areas claimed by the Islamic State /ˈaɪsɪ/). -

Download The

A PUBLICATION OF THE INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF WAR AND WEEKLYSTANDARD.COM A PUBLICATION OF THE INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF WAR AND WEEKLYSTANDARD.COM U.S. Army Lt. Gen. Ray Odierno, commander of Multi-National Corps - Iraq, reviews a map with Capt. Eric Lawless, of the 1st Battalion, 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment, at Forward Operating Base Iskandariyah in Iraq on Dec. 25, 2006. (U.S. Army photo by Sgt. Curt Cashour) February 14 – June 15, 2007 The Real Surge: Preparing for Operation Phantom Thunder by KIMBERLY KAGAN Summary On June 15, 2007, Generals David Petraeus and Ray Odierno launched the largest coordinated military operation in Iraq since the initial U.S. invasion. The campaign, called Operation Phantom Thunder, aims to expel al Qaeda from its sanctuaries just outside of Baghdad. Denying al Qaeda the ability to fabricate car bombs and transport fi ghters through the rural terrain around Baghdad is a necessary prerequisite for securing the capital city, the overarching military goal for Iraq in 2007. Phantom Thunder consists of simultaneous offensives by U.S. forces throughout central Iraq. The Division north of Baghdad cleared the long-festering city of Baqubah and its outlying areas. The Division east and southeast of Baghdad is clearing the critical al Qaeda stronghold in Arab Jabour, immediately south of the capital. It is also destroying al Qaeda’s ability to transport weapons along the Tigris River and to send reinforcements from the Euphrates to the Tigris. The Division west of Baghdad is clearing al Qaeda’s sanctuaries between Fallujah and Baghdad, all the way to the shores of Lake Tharthar northwest of the capital. -

U.S. Military Casualties - Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) Names of Fallen

U.S. Military Casualties - Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) Names of Fallen (As of May 22, 2015) Service Component Name (Last, First M) Rank Pay Grade Date of Death Age Gender Home of Record Home of Record Home of Record Home of Record Unit Incident Casualty Casualty Country City of Loss (yyyy/mm/dd) City County State Country Geographic Geographic Code Code MARINE ACTIVE DUTY ABAD, ROBERTO CPL E04 2004/08/06 22 MALE BELL GARDENS LOS ANGELES CA US WPNS CO, BLT 1/4, 11TH MEU, CAMP PENDLETON, CA IZ IZ IRAQ NAJAF CORPS NAVY ACTIVE DUTY ACEVEDO, JOSEPH CDR O05 2003/04/13 46 MALE BRONX BRONX NY US NAVSUPPACT BAHRAIN BA BA BAHRAIN MANAMA ARMY ACTIVE DUTY ACEVEDOAPONTE, RAMON SFC E07 2005/10/26 51 MALE WATERTOWN JEFFERSON NY US HHC, 3D COMBAT SUPPORT BATTALION, TF BAGHDAD, IZ IZ IRAQ RUSTAMIYAH ANTONIO FORT STEWART, GA ARMY ACTIVE DUTY ACKLIN, MICHAEL DEWAYNE II SGT E05 2003/11/15 25 MALE LOUISVILLE JEFFERSON KY US C BATTERY 1ST BATTALION 320TH FIELD ARTILLERY, IZ IZ IRAQ MOSUL REGIMENT FORT CAMPBELL, KY 42223 ARMY ACTIVE DUTY ACOSTA, GENARO SPC E04 2003/11/12 26 MALE FAIR OAKS MULTIPLE CA US BATTERY B, 1ST BATTALION, 44TH AIR DEFENSE IZ IZ IRAQ TAJI ARTILLERY, FORT HOOD, TX 76544 ARMY ACTIVE DUTY ACOSTA, STEVEN PFC E03 2003/10/26 19 MALE CALEXICO IMPERIAL CA US COMPANY C, 3D BATTALION, 67TH ARMOR REGIMENT, IZ IZ IRAQ BA'QUBAH FORT HOOD, TX 76544 ARMY ACTIVE DUTY ADAIR, JAMES LEE SPC E03 2007/06/29 26 MALE CARTHAGE PANOLA TX US COMPANY B, 1ST BATTALION, 28TH INFANTRY, 4 BCT, IZ IZ IRAQ BAGHDAD FORT RILEY, KS ARMY ACTIVE DUTY ADAMOUSKI, JAMES FRANCIS -

ARMOR March-April 2003

Once More Unto the Breach As we go to print, diplomatic efforts to resolve Iraqi disarma- fect or incomplete information, but the friction generated in the ment issues have almost reached the terminal stage. Unless a commander’s mind by uncertainty, exhaustion, and fear. Captain significant breakthrough occurs, U.S. Armed Forces will once Scott Thomson advises that heavy cavalry is designed to fight again act as the hammer. I know we are up to the task, but we for information. However, the distances over which the troop cannot become overconfident in our equipment, tactics, and operates, combined with the uncertain enemy situation inherent soldiers. Our leaders must stay focused on the basics and main- in being the first force to cross the battlefield, presents the com- tain our high standards. Good luck to all. mander with the most difficult situation in which to concentrate his firepower. This is what makes the cavalry mission a danger- The Battle of Kursk is considered one of the most epic tank ous and frustrating one. battles of all time. To the Germans, it was an opportunity to repeat their 1941 and 1942 successes, encircling vast Soviet Transforming the armor cavalry force remains a topic of consid- armies and destroying them in the process. The German losses erable discussion. Captain Ryan Seagreaves provides insight on are put at over 3,500 armored vehicles, with the true number how to effectively transform the Task Force Scout Platoon. Sea- unknown. To both sides, the salient around Kursk — 200 kilo- greaves proposes the critical limitations of the Task Force (TF) meters wide and 150 deep — was the single most obvious tar- HMMWV Scout Platoon can be corrected by a transformation to get for the Germans to attack. -

Securing Diyala

A PUBLICATION OF THE INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF WAR AND WEEKLYSTANDARD.COM A PUBLICATION OF THE INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF WAR AND WEEKLYSTANDARD.COM U.S. Army Lt. Col. Brian J. Cummins (upper left) discusses current and future cooperation with a concerned local Iraqi, Sheik Ahmad Huassne and Iraqi army Brig. Gen. Gaillan. Iraqi army, Iraqi police and concerned nationals combined efforts to conduct a raid against a suspected al-Qaida in Iraq stronghold, Sept. 2. (Photo by 1st Lt. Richard Ybarra, 115th Mobile Public Affairs Detachment.) June 2007-November 2007 Securing Diyala by KIMBERLY KAGAN U.S. forces drove al Qaeda in Iraq from its sanctuaries in Diyala in 2007 and dramatically reduced violence in that province. Defeating al Qaeda in Diyala was especially important because the province had political, as well as military signifi cance for al Qaeda. The organization attempted to establish the capital of its Islamic state there. The task of defeating violent enemies in Diyala and establishing a political process there was also exceptionally more diffi cult. The enemy controlled Baqubah, the capital of Diyala, so thoroughly that it had fortifi ed defensive positions within the city. The enemy also controlled the rural terrain along the province’s roads and rivers. The ethnic and sectarian diversity of Diyala’s population amplifi ed the opportunities for al Qaeda’s violence and its effects, including reprisal violence by Shia militias, security forces, and neighboring villages. Re-establishing security in Diyala required a series of offensive operations over four months, all aimed at controlling urban areas, rural terrain, and lines of communication (roads and rivers). -

Beyond “Hearts and Minds”

BEYOND “HEARTS AND MINDS” A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government By Raphael S. Cohen, M.A. Washington, DC May 15, 2014 Copyright 2014 by Raphael S. Cohen All Rights Reserved ii BEYOND “HEARTS AND MINDS” Raphael S. Cohen, M.A. Dissertation Advisor: Daniel L. Byman, Ph.D. ABSTRACT: Ever since Field Marshal Sir Gerald Templer proclaimed that “the answer lies not in pouring more troops into the jungle, but in the hearts and minds of the people,” common wisdom suggests that the key to military victory in counterinsurgency is “winning hearts and minds.” As interpreted in modern doctrine, Templer’s dictum requires that the counterinsurgent promote economic, social and political reforms (to give everyone a “stake” in society) and minimize its use of force (to avoid popular backlash). My dissertation shows that 1) historically, most successful counterinsurgencies have not been fought this way; 2) when this approach has been tried, it rarely proves effective; and 3) instead, military victory comes from successful population control. Population control, in turn, employs some combination of three sets of tactics: physical measures (e.g. walls, resource controls and forced resettlement), cooption (of local elite and often the insurgents themselves) and “divide and rule” strategies. I demonstrate these claims through detailed analyses of four influential modern counterinsurgencies—the Malayan Emergency, the Mau Mau Rebellion, the Vietnam War and the Iraq War, along with a study of local opinion data from the Vietnam, Iraq and Afghan Wars. -

Future of Defense

Issue 63, 4th Quarter 2011 FUTURE OF DEFENSE CYBER STRATEGY 2011 ESSAY CONTEST WINNERS JOINT FORCE QUARTERLY Inside Issue 63, 4th Quarter 2011 Editor Col William T. Eliason, USAF (Ret.), Ph.D. JFQ Dialogue Executive Editor Jeffrey D. Smotherman, Ph.D. Supervisory Editor George C. Maerz Letters to the Editor 2 Production Supervisor Martin J. Peters, Jr. In Memoriam: How General John Shalikashvili “Paid It Forward” to Senior Copy Editor Calvin B. Kelley 4 500,000 Others By Andrew Marble Book Review Editor Lisa M. Yambrick Visual Design Editor Tara J. Parekh Forum Copy Editor/Office Manager John J. Church, D.M.A Internet Publications Editor Joanna E. Seich Executive Summary 6 Design Jon Raedeke, Jamie Harvey, Chris Dunham, U.S. Government Printing Office 8 An Interview with Norton A. Schwartz The Looming Crisis in Defense Planning By Paul K. Davis and Printed in St. Louis, Missouri 13 Peter A. Wilson by 21 Thoughts on Force Design in an Era of Shrinking Defense Budgets By Douglas A. Macgregor NDU Press is the National Defense University’s Linking Military Service Budgets to Commander Priorities cross-component, professional military and 30 academic publishing house. It publishes books, By Mark A. Gallagher and M. Kent Taylor journals, policy briefs, occasional papers, monographs, and special reports on national 38 Harnessing America’s Power: A U.S. National Security Structure for the security strategy, defense policy, interagency 21st Century By Peter C. Phillips and Charles S. Corcoran cooperation, national military strategy, regional security affairs, and global strategic problems. 47 The Limits of Tailored Deterrence By Sean P.