UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SHERLOC Newsletter Organized, As “New” Groups And/Or Networks Focusses on the Topic of Cybercrime and Operating Online Have Been Formed

N E W S L E T T E R I S S U E N O . 1 6 | N O V E M B E R 2 0 2 0 The SHERLOC Team is pleased to share with you Issue No. 16 of our newsletter regarding our recent efforts to facilitate the dissemination of information regarding the implementation of the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime and the Protocols thereto, and the international legal framework against terrorism. #0211w In this issue Today, we stand close to the many thousands victims of FEATURED CASE: terrorism and their families all around the world, including ELYSIUM PLATFORM those of the recent Vienna attacks, our host country and home to many of us within the team. We stand by those many victims "struggling in their solitude with the scars of trauma and injury" as "their human rights and dignity have been violated with indiscriminate violence. Only the UNTOC COP10 acknowledgment of their suffering can start their healing; only information-sharing can overcome their isolation; only specialized rehabilitation and redress can help them rebuild their lives" (Laura Dolci, victim of the Canal Hotel bombing in Iraq of 2003). RECENT ACTIVITIES Today, our prayers and thoughts go to all the victims and survivors of terrorism around the world. We reaffirm our strong commitment to facilitate information-sharing as a means to build knowledge and expertise to counter crime, in MEET A CONTRIBUTOR all its forms and manifestations, including terrorism. The SHERLOC team N O V E M B E R 2 0 2 0 I S S U E N O . -

Full Complaint

Case 1:18-cv-01612-CKK Document 11 Filed 11/17/18 Page 1 of 602 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ESTATE OF ROBERT P. HARTWICK, § HALEY RUSSELL, HANNAH § HARTWICK, LINDA K. HARTWICK, § ROBERT A. HARTWICK, SHARON § SCHINETHA STALLWORTH, § ANDREW JOHN LENZ, ARAGORN § THOR WOLD, CATHERINE S. WOLD, § CORY ROBERT HOWARD, DALE M. § HINKLEY, MARK HOWARD BEYERS, § DENISE BEYERS, EARL ANTHONY § MCCRACKEN, JASON THOMAS § WOODLIFF, JIMMY OWEKA OCHAN, § JOHN WILLIAM FUHRMAN, JOSHUA § CRUTCHER, LARRY CRUTCHER, § JOSHUA MITCHELL ROUNTREE, § LEIGH ROUNTREE, KADE L. § PLAINTIFFS’ HINKHOUSE, RICHARD HINKHOUSE, § SECOND AMENDED SUSAN HINKHOUSE, BRANDON § COMPLAINT HINKHOUSE, CHAD HINKHOUSE, § LISA HILL BAZAN, LATHAN HILL, § LAURENCE HILL, CATHLEEN HOLY, § Case No.: 1:18-cv-01612-CKK EDWARD PULIDO, KAREN PULIDO, § K.P., A MINOR CHILD, MANUEL § Hon. Colleen Kollar-Kotelly PULIDO, ANGELITA PULIDO § RIVERA, MANUEL “MANNIE” § PULIDO, YADIRA HOLMES, § MATTHEW WALKER GOWIN, § AMANDA LYNN GOWIN, SHAUN D. § GARRY, S.D., A MINOR CHILD, SUSAN § GARRY, ROBERT GARRY, PATRICK § GARRY, MEGHAN GARRY, BRIDGET § GARRY, GILBERT MATTHEW § BOYNTON, SOFIA T. BOYNTON, § BRIAN MICHAEL YORK, JESSE D. § CORTRIGHT, JOSEPH CORTRIGHT, § DIANA HOTALING, HANNA § CORTRIGHT, MICHAELA § CORTRIGHT, LEONDRAE DEMORRIS § RICE, ESTATE OF NICHOLAS § WILLIAM BAART BLOEM, ALCIDES § ALEXANDER BLOEM, DEBRA LEIGH § BLOEM, ALCIDES NICHOLAS § BLOEM, JR., VICTORIA LETHA § Case 1:18-cv-01612-CKK Document 11 Filed 11/17/18 Page 2 of 602 BLOEM, FLORENCE ELIZABETH § BLOEM, CATHERINE GRACE § BLOEM, SARA ANTONIA BLOEM, § RACHEL GABRIELA BLOEM, S.R.B., A § MINOR CHILD, CHRISTINA JEWEL § CHARLSON, JULIANA JOY SMITH, § RANDALL JOSEPH BENNETT, II, § STACEY DARRELL RICE, BRENT § JASON WALKER, LELAND WALKER, § SUSAN WALKER, BENJAMIN § WALKER, KYLE WALKER, GARY § WHITE, VANESSA WHITE, ROYETTA § WHITE, A.W., A MINOR CHILD, § CHRISTOPHER F. -

The Hostage Through the Ages

Volume 87 Number 857 March 2005 A haunting figure: The hostage through the ages Irène Herrmann and Daniel Palmieri* Dr Irène Herrmann is Lecturer at the University of Geneva; she is a specialist in Swiss and in Russian history. Daniel Palmieri is Historical Research Officer at the International Committee of the Red Cross; his work deals with ICRC history and history of conflicts. Abstract: Despite the recurrence of hostage-taking through the ages, the subject of hostages themselves has thus far received little analysis. Classically, there are two distinct types of hostages: voluntary hostages, as was common practice during the Ancien Régime of pre-Revolution France, when high-ranking individuals handed themselves over to benevolent jailers as guarantors for the proper execution of treaties; and involuntary hostages, whose seizure is a typical procedure in all-out war where individuals are held indiscriminately and without consideration, like living pawns, to gain a decisive military upper hand. Today the status of “hostage” is a combination of both categories taken to extremes. Though chosen for pecuniary, symbolic or political reasons, hostages are generally mistreated. They are in fact both the reflection and the favoured instrument of a major moral dichotomy: that of the increasing globalization of European and American principles and the resultant opposition to it — an opposition that plays precisely on the western adherence to human and democratic values. In the eyes of his countrymen, the hostage thus becomes the very personification of the innocent victim, a troubling and haunting image. : : : : : : : In the annals of the victims of war, hostages occupy a special place. -

Congressional Record—Senate S4700

S4700 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE August 2, 2017 required. American workers have wait- of Kansas, to be a Member of the Na- billion each year in State and local ed too long for our country to crack tional Labor Relations Board for the taxes. down on abusive trade practices that term of five years expiring August 27, As I said at the beginning, I have had rob our country of millions of good- 2020. many differences with President paying jobs. The PRESIDING OFFICER. Under Trump, particularly on the issue of im- Today, I am proud to announce that the previous order, the time until 11 migration in some of the speeches and the Democratic Party will be laying a.m. will be equally divided between statements he has made, but I do ap- out our new policy on trade, which in- the two leaders or their designees. preciate—personally appreciate—that cludes, among other things, an inde- The assistant Democratic leader. this President has kept the DACA Pro- pendent trade prosecutor to combat DACA gram in place. trade cheating, not one of these endless Mr. DURBIN. Mr. President, many I have spoken directly to President WTO processes that China takes advan- times over the last 6 months, I have Trump only two times—three times, tage of over and over again; a new come to the Senate to speak out on perhaps. The first two times—one on American jobs security council that issues and to disagree with President Inauguration Day—I thanked him for will be able to review and stop foreign Trump. -

United Nations Nations Unies Office for the Coordination Of

United Nations Nations Unies Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs As delivered Under-Secretary-General Valerie Amos Opening remarks at event marking the Tenth Anniversary of the Canal Hotel Bombing Rio de Janeiro, 19 August 2013 It is a great privilege to be here in Brazil with you on the tenth anniversary of the bomb attack that took the lives of 22 people including Sergio Vieira de Mello. The attack on the Canal Hotel is still shocking, horrifying to us ten years on, because it was deliberate and targeted against Sergio and his colleagues who were in Iraq to help people in need. It violated every principle of humanity and solidarity, the principles on which the UN is founded. Today we not only remember Sergio and his colleagues, but also so many friends and of course colleagues who survived the attack. We commemorate Sergio’s life and work in Brazil and on the international stage through the marking of World Humanitarian Day, when we remember all the humanitarian aid workers who have given their lives in order to help people in need. Sergio’s name resonates in the UN building in New York and everywhere he worked around the world: the charismatic leader, the fearless humanitarian. His ideals, commitment and energy remain an inspiration to us all. Ladies and gentlemen, The attack on Sergio Vieira de Mello, and the other people who died at the Canal Hotel that day, was a senseless waste of human life and by forcing the UN to reduce its work in Iraq, it was an indirect attack on some of the most vulnerable people in the world. -

Pdf | 231.42 Kb

United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI) UNAMI FOCUS Voice of the Mission News Bulletin on UNAMI Activities Issue No. 18 December 2007 SRSG Staffan de Mistura in Baghdad that Iraq will spend $900 million on capital 12 Nov 2007 projects across Baghdad. The conference In his first town-hall meeting address to was hosted by the Deputy Prime Minister, UNAMI staff, Special Representative of the Barham Saleh, the two Vice Presidents, Secretary General for Iraq Staffan de Adel Abd-al-Mahdi and Tareq Al-Hashimi, Mistura, reiterated his commitment to fulfill Baghdad’s Mayor, Saber Al-Essawi, UNAMI’s mandate as stated in UNSCR Baghdad’s Governor, Ali Muyassar, and the 1770. He emphasized that special attention commander of the Baghdad Security Plan, will be given to national reconciliation and Abboud Qunbur. national dialogue as stated in the resolution, SRSG Staffan de Mistura Paying Tribute to which clearly calls for a larger UN role in the victims of the Canal Hotel Bombing the country. He expressed the hope that this expansion will lead to tangible results, and UNAMI Focus Interview with the that no effort will be spared by the Mission SRSG, Mr. Staffan de Mistura towards achieving its stated goals. UNAMI Focus: Can you provide the Mr. de Mistura said that his immediate UNAMI Focus readers with a synopsis of priorities are to quickly assume his responsibilities and take initiative to ensure your priorities, along with the things you Baghdad Rehabilitation Day that his activities and initiatives are felt in hope to achieve, in Iraq for the upcoming the country, as well as making certain that year? To launch the initiative, Deputy Prime his, are consistent with those priorities of Minister Barham Saleh extended an his Iraqi counterparts. -

Kidnapping Is Booming Business

Colophon Published by IKV Pax Christi, July 2008 Also printed in Dutch and Spanish Address P.O. Box 19318 3501 DH UTRECHT The Netherlands www.ikvpaxchristi.nl [email protected] Circulation 300 copies Text IKV Pax Christi Marianne Moor Simone Remijnse With the cooperation of: Fundación País Libre, Ms. Olga Lucía Gómez Fundación País Libre, Ms. Claudia M. Llano Rodrigo Rojas Orozco Mauricio Silva Peer van Doormalen Paul Wolters Bart Weerdenburg Sarah Lachman Annemieke van Breukelen Carolien Groeneveld ISBN 978-90-70443-41-2 Design & Print Van der Weij BV Netherlands Contents Introduction 3 1 Growth on all fronts: kidnapping in a global context 5 1.1.. A study of kidnapping worldwidel 5 1.2. Kidnapping in the 21st century; risers and fallers 5 1.3. A tried and tested weapon in the struggle 7 1.4. A profitable sideline that delivers fast 7 1.5. The middle classes protest 8 1.6. The heavy hand used selectively 8 2. Kidnapping in the regions 11 2.1. Africa 11 2.1.1. Nigeria 12 2.2. Asia 12 2.3. The Middle East 15 2.3.1. Iraq 15 2.4. Latin America 16 2.4.1. A wave of kidnapping in the major cities 17 2.4.2. Central America: maras and criminal gangs 18 2.4.3. The Colombianization of Mexico and Trinidad &Tobago 18 2.4.4. Kidnapping and the Colombian conflict 20 3. The regionalization of a Colombian practice: 25 kidnapping in Colombia, Ecuador and Venezuela 3.1. The kidnapping problem: 1995 – 2001 25 3.2. -

Iraq: U.S. Regime Change Efforts and Post-Saddam Governance

Order Code RL31339 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Iraq: U.S. Regime Change Efforts and Post-Saddam Governance Updated May 16, 2005 Kenneth Katzman Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Iraq: U.S. Regime Change Efforts and Post-Saddam Governance Summary Operation Iraqi Freedom accomplished a long-standing U.S. objective, the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, but replacing his regime with a stable, moderate, democratic political structure has been complicated by a persistent Sunni Arab-led insurgency. The Bush Administration asserts that establishing democracy in Iraq will catalyze the promotion of democracy throughout the Middle East. The desired outcome would also likely prevent Iraq from becoming a sanctuary for terrorists, a key recommendation of the 9/11 Commission report. The Bush Administration asserts that U.S. policy in Iraq is now showing substantial success, demonstrated by January 30, 2005 elections that chose a National Assembly, and progress in building Iraq’s various security forces. The Administration says it expects that the current transition roadmap — including votes on a permanent constitution by October 31, 2005 and for a permanent government by December 15, 2005 — are being implemented. Others believe the insurgency is widespread, as shown by its recent attacks, and that the Iraqi government could not stand on its own were U.S. and allied international forces to withdraw from Iraq. Some U.S. commanders and senior intelligence officials say that some Islamic militants have entered Iraq since Saddam Hussein fell, to fight what they see as a new “jihad” (Islamic war) against the United States. -

Influence Evaluation of PM10 Produced by the Burning of Biomass in Peru on AOD, Using the WRF-Chem

Atmósfera 33(1), 71-86 (2020) doi: 10.20937/ATM.52711 Influence evaluation of PM10 produced by the burning of biomass in Peru on AOD, using the WRF-Chem Héctor NAVARRO-BARBOZA1,2,3*, Aldo MOYA-ÁLVAREZ2, Ana LUNA1 and Octavio FASHÉ-RAYMUNDO3 1 Universidad del Pacífico, Av. Salaverry 2020, Jesús María, Lima 11, Perú. 2 Instituto Geofísico del Perú, Lima, Perú. 3 Facultad de Ciencias Físicas, Unidad de Posgrado, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Calle Germán Amezaga 375, Lima, Perú. * Corresponding author; e-mail: [email protected] Received: April 22, 2019; accepted: October 9, 2019 RESUMEN En este estudio se evalúa la influencia de partículas PM10 en el espesor óptico de aerosoles en los Andes centrales del Perú, además de analizar y establecer los patrones de circulación en la región desde julio hasta octubre de 2017. Se considera este periodo en particular porque los mayores eventos de quema de biomasa se registran generalmente durante esos meses. Se utilizó el modelo regional de transporte meteorológico-químico WRF-Chem (versión 3.7) con el Inventario de Incendios del NCAR (FINN) y los datos de espesor óptico de aerosoles (EOA) de la Red de Monitoreo de Redes Robóticas de Aerosoles (AERONET), que cuenta con un fotómetro solar CIMEL ubicado en el observatorio de Huancayo, la ciudad más importante del altiplano central del Perú. La simulación empleó un único dominio con un tamaño de cuadrícula de 18 km y 32 niveles verticales. Los resultados mostraron un incremento en las concentraciones de PM10 con un aumento en el número de brotes de incendio y en el EOA durante julio, agosto y septiembre. -

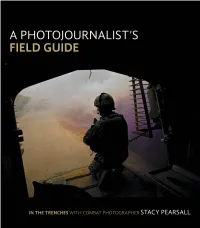

A Photojournalist's Field Guide: in the Trenches with Combat Photographer

A PHOTOJOURNALISt’S FIELD GUIDE IN THE TRENCHES WITH COMBAT PHOTOGRAPHER STACY PEARSALL A Photojournalist’s Field Guide: In the trenches with combat photographer Stacy Pearsall Stacy Pearsall Peachpit Press www.peachpit.com To report errors, please send a note to [email protected] Peachpit Press is a division of Pearson Education. Copyright © 2013 by Stacy Pearsall Project Editor: Valerie Witte Production Editor: Katerina Malone Copyeditor: Liz Welch Proofreader: Erin Heath Composition: WolfsonDesign Indexer: Valerie Haynes Perry Cover Photo: Stacy Pearsall Cover and Interior Design: Mimi Heft Notice of Rights All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or trans- mitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy- ing, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For information on getting permission for reprints and excerpts, contact [email protected]. Notice of Liability The information in this book is distributed on an “As Is” basis, without warranty. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of the book, neither the author nor Peachpit shall have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the instructions contained in this book or by the computer software and hardware products described in it. Trademarks Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and Peachpit was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations appear as requested by the owner of the trademark. -

70Th Annual 1St Cavalry Division Association Reunion

1st Cavalry Division Association 302 N. Main St. Non-Profit Organization Copperas Cove, Texas 76522-1703 US. Postage PAID West, TX Change Service Requested 76691 Permit No. 39 PublishedSABER By and For the Veterans of the Famous 1st Cavalry Division VOLUME 66 NUMBER 1 Website: http://www.1cda.org JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2017 The President’s Corner Horse Detachment by CPT Jeremy A. Woodard Scott B. Smith This will be my last Horse Detachment to Represent First Team in Inauguration Parade By Sgt. 833 State Highway11 President’s Corner. It is with Carolyn Hart, 1st Cav. Div. Public Affairs, Fort Hood, Texas. Laramie, WY 82070-9721 deep humility and considerable A long standing tradition is being (307) 742-3504 upheld as the 1st Cavalry Division <[email protected]> sorrow that I must announce my resignation as the President Horse Cavalry Detachment gears up to participate in the Inauguration of the 1st Cavalry Division Association effective Saturday, 25 February 2017. Day parade Jan. 20 in Washington, I must say, first of all, that I have enjoyed my association with all of you over D.C. This will be the detachment’s the years…at Reunions, at Chapter meetings, at coffees, at casual b.s. sessions, fifth time participating in the event. and at various activities. My assignments to the 1st Cavalry Division itself and “It’s a tremendous honor to be able my friendships with you have been some of the highpoints of my life. to do this,” Capt. Jeremy Woodard, To my regret, my medical/physical condition precludes me from travelling. -

A Symposium for John Perry Barlow

DUKE LAW & TECHNOLOGY REVIEW Volume 18, Special Symposium Issue August 2019 Special Editor: James Boyle THE PAST AND FUTURE OF THE INTERNET: A Symposium for John Perry Barlow Duke University School of Law Duke Law and Technology Review Fall 2019–Spring 2020 Editor-in-Chief YOOJEONG JAYE HAN Managing Editor ROBERT HARTSMITH Chief Executive Editors MICHELLE JACKSON ELENA ‘ELLIE’ SCIALABBA Senior Research Editors JENNA MAZZELLA DALTON POWELL Special Projects Editor JOSEPH CAPUTO Technical Editor JEROME HUGHES Content Editors JOHN BALLETTA ROSHAN PATEL JACOB TAKA WALL ANN DU JASON WASSERMAN Staff Editors ARKADIY ‘DAVID’ ALOYTS ANDREW LINDSAY MOHAMED SATTI JONATHAN B. BASS LINDSAY MARTIN ANTHONY SEVERIN KEVIN CERGOL CHARLES MATULA LUCA TOMASI MICHAEL CHEN DANIEL MUNOZ EMILY TRIBULSKI YUNA CHOI TREVOR NICHOLS CHARLIE TRUSLOW TIM DILL ANDRES PACIUC JOHN W. TURANCHIK PERRY FELDMAN GERARDO PARRAGA MADELEINE WAMSLEY DENISE GO NEHAL PATEL SIQI WANG ZACHARY GRIFFIN MARQUIS J. PULLEN TITUS R. WILLIS CHARLES ‘CHASE’ HAMILTON ANDREA RODRIGUEZ BOUTROS ZIXUAN XIAO DAVID KIM ZAYNAB SALEM CARRIE YANG MAX KING SHAREEF M. SALFITY TOM YU SAMUEL LEWIS TIANYE ZHANG Journals Advisor Faculty Advisor Journals Coordinator JENNIFER BEHRENS JAMES BOYLE KRISTI KUMPOST TABLE OF CONTENTS Authors’ Biographies ................................................................................ i. John Perry Barlow Photograph ............................................................... vi. The Past and Future of the Internet: A Symposium for John Perry Barlow James Boyle