A Photojournalist's Field Guide: in the Trenches with Combat Photographer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mark Seymour Life of a Documentary Photographer

Online Issue 2 - February 2017 MARK SEYMOUR LIFE OF A DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHER THE SOCIETIES AWARD WINNING IMAGES OF 2016 BASICS WITH BRIAN “THE BRAIN” 10 ESSENTIAL PHOTOSHOP EFX WITH MARK CLEGHORN ACADEMY LIVE CRIT TOP TEN COMMENTS PIMP MY PICTURE GARDEN MACRO TIPS WITH MICHELLE WHITMORE ZEISS LENS REVIEW WITH LISA BEANEY BIG PHOTO COMPETITION - WELCOME TO THE BIG PHOTO E-ZINE HEADSHOTS elcome to the second issue of The Big Photo, we hope the first informed and enlightened you in some way. WThis month we’re brining you another fantastic variety ROADSHOW of content, a amazing Architectural Image of the month, an insight into the world of Top Documentary & Wedding photographer Mark Seymour, Garden Macro tips, Mark Cleghorn’s essential Photoshop EFX, and much much more. inspire The Big Photo is ultimately designed as a celebration of The Photographer Academy create photography and photographers, so this month we also brining you some of the amazing winning images from the SWPP 2016 Photographer of the Year is proud to present The Big awards. These images show the amazing quality of images being produced today and Photo UK Roadshow 2017 hopefully inspires you to shoot that little bit better every day. and this year it’s all about Remember you can get your images featured to, if you make the top ten in our monthly Headshots! critique then your image will appear in the magazine. Also, don’t forget The Big Photo is Bringing you specific training including Business, an interactive Ezine, so look for links to take you directly to more great content from The Lighting, Posing, Pricing, Products and finishing the Photographer Academy and our partners. -

Congressional Record—Senate S4700

S4700 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE August 2, 2017 required. American workers have wait- of Kansas, to be a Member of the Na- billion each year in State and local ed too long for our country to crack tional Labor Relations Board for the taxes. down on abusive trade practices that term of five years expiring August 27, As I said at the beginning, I have had rob our country of millions of good- 2020. many differences with President paying jobs. The PRESIDING OFFICER. Under Trump, particularly on the issue of im- Today, I am proud to announce that the previous order, the time until 11 migration in some of the speeches and the Democratic Party will be laying a.m. will be equally divided between statements he has made, but I do ap- out our new policy on trade, which in- the two leaders or their designees. preciate—personally appreciate—that cludes, among other things, an inde- The assistant Democratic leader. this President has kept the DACA Pro- pendent trade prosecutor to combat DACA gram in place. trade cheating, not one of these endless Mr. DURBIN. Mr. President, many I have spoken directly to President WTO processes that China takes advan- times over the last 6 months, I have Trump only two times—three times, tage of over and over again; a new come to the Senate to speak out on perhaps. The first two times—one on American jobs security council that issues and to disagree with President Inauguration Day—I thanked him for will be able to review and stop foreign Trump. -

Photography: a Survey of New Reference Sources

RSR: Reference Services Review. 1987, v.15, p. 47 -54. ISSN: 0090-7324 Weblink to journal. ©1987 Pierian Press Current Surveys Sara K. Weissman, Column Editor Photography: A Survey of New Reference Sources Eleanor S. Block What a difference a few years make! In the fall 1982 issue of Reference Services Review I described forty reference monographs and serial publications on photography. That article concluded with these words, "a careful reader will be aware that not one single encyclopedia or solely biographical source was included... this reviewer could find none in print... A biographical source proved equally elusive" (p.28). Thankfully this statement is no longer valid. Photography reference is greatly advanced and benefited by a number of fine biographical works and a good encyclopedia published in the past two or three years. Most of the materials chosen for this update, as well as those cited in the initial survey article, emphasize the aesthetic nature of photography rather than its scientific or technological facets. A great number of the forty titles in the original article are still in print; others have been updated. Most are as valuable now as they were then for good photography reference selection. However, only those sources published since 1982 or those that were not cited in the original survey have been included. This survey is divided into six sections: Biographies, Dictionaries (Encyclopedias), Bibliographies, Directories, Catalogs, and Indexes. BIOGRAPHIES Three of the reference works cited in this survey have filled such a lamented void in photography reference literature that they stand above the rest in their importance and value. -

Download the Free Pdf of Volume I

9 volume 1 200 DiffusionUnconventional Photography Articles: Profiles: Group Showcase: I’m Often Asked... An Ironic Manifesto Jeffrey Baker Pamela Petro Formerly & Hereafter by Zeb Andrews by Dr. Mike Ware Tina Maas Sika Stanton Plates to Pixels Juried Show Praise for Diffusion, Volume I “Avant-garde, breakthrough and innovative are just three adjectives that describe editor Blue Mitchell’s first foray into the world of fine art photography magazines. Diffusion magazine, tagged as unconventional photography delivers on just that. Volume 1 features the work of Jeffrey Baker, Pamela Petro, Tina Maas and Sika Stanton. With each artist giving you a glimpse into how photography forms an integral part of each of their creative journey. The first issue’s content is rounded out by Zeb Andrews’ and Dr. Mike Ware. Zeb Andrews’ peak through his pin-hole world is complimented by an array of his creations along with the 900 second exposure “Fun Center” as the show piece. And Dr. Mike unscrambles the history of iron-based photographic processes and the importance of the printmaker in the development of a fine art image. At a time when we are seeing a mass migration to on-line publishing and on-line magazine hosting, the editorial team at Diffusion proves you can still deliver an outstanding hard-copy fine art photography magazine. I consumed my copy immediately with delight; now when is the next issue coming out?” - Michael Van der Tol “Regardless of the retrospective approach to the medium of photography, which could be perceived by many as a conservative drive towards nostalgia and sentimentality. -

70Th Annual 1St Cavalry Division Association Reunion

1st Cavalry Division Association 302 N. Main St. Non-Profit Organization Copperas Cove, Texas 76522-1703 US. Postage PAID West, TX Change Service Requested 76691 Permit No. 39 PublishedSABER By and For the Veterans of the Famous 1st Cavalry Division VOLUME 66 NUMBER 1 Website: http://www.1cda.org JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2017 The President’s Corner Horse Detachment by CPT Jeremy A. Woodard Scott B. Smith This will be my last Horse Detachment to Represent First Team in Inauguration Parade By Sgt. 833 State Highway11 President’s Corner. It is with Carolyn Hart, 1st Cav. Div. Public Affairs, Fort Hood, Texas. Laramie, WY 82070-9721 deep humility and considerable A long standing tradition is being (307) 742-3504 upheld as the 1st Cavalry Division <[email protected]> sorrow that I must announce my resignation as the President Horse Cavalry Detachment gears up to participate in the Inauguration of the 1st Cavalry Division Association effective Saturday, 25 February 2017. Day parade Jan. 20 in Washington, I must say, first of all, that I have enjoyed my association with all of you over D.C. This will be the detachment’s the years…at Reunions, at Chapter meetings, at coffees, at casual b.s. sessions, fifth time participating in the event. and at various activities. My assignments to the 1st Cavalry Division itself and “It’s a tremendous honor to be able my friendships with you have been some of the highpoints of my life. to do this,” Capt. Jeremy Woodard, To my regret, my medical/physical condition precludes me from travelling. -

Rental Catalog Lighting • Grip

RENTAL CATALOG LIGHTING • GRIP SAMYS.COM/RENT TABLE OF CONTENTS STROBE LIGHTING PROFOTO ....................................................................................................................1 BRONCOLOR ..............................................................................................................6 GODOX VIDEO LIGHT ............................................................................................... 10 POWER INVERTERS .................................................................................................. 10 QUANTUM FLASHES & SLAVES ................................................................................. 11 SOFT LIGHTS ............................................................................................................12 BRIESE LIGHTING & ACCESSORIES ...........................................................................13 LIGHT BANKS ............................................................................................................14 POCKET WIZARD REMOTE TRIGGERS .......................................................................15 METERS EXPOSURE METERS ..................................................................................................16 CONTINUOUS LIGHTING LED / TUNGSTEN / HMI .............................................................................................18 HMI LIGHTING ...........................................................................................................19 LED LIGHTS ...............................................................................................................21 -

The Development and Growth of British Photographic Manufacturing and Retailing 1839-1914

The development and growth of British photographic manufacturing and retailing 1839-1914 Michael Pritchard Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Imaging and Communication Design Faculty of Art and Design De Montfort University Leicester, UK March 2010 Abstract This study presents a new perspective on British photography through an examination of the manufacturing and retailing of photographic equipment and sensitised materials between 1839 and 1914. This is contextualised around the demand for photography from studio photographers, amateurs and the snapshotter. It notes that an understanding of the photographic image cannot be achieved without this as it directly affected how, why and by whom photographs were made. Individual chapters examine how the manufacturing and retailing of photographic goods was initiated by philosophical instrument makers, opticians and chemists from 1839 to the early 1850s; the growth of specialised photographic manufacturers and retailers; and the dramatic expansion in their number in response to the demands of a mass market for photography from the late1870s. The research discusses the role of technological change within photography and the size of the market. It identifies the late 1880s to early 1900s as the key period when new methods of marketing and retailing photographic goods were introduced to target growing numbers of snapshotters. Particular attention is paid to the role of Kodak in Britain from 1885 as a manufacturer and retailer. A substantial body of newly discovered data is presented in a chronological narrative. In the absence of any substantive prior work this thesis adopts an empirical approach firmly rooted in the photographic periodicals and primary sources of the period. -

Elb 500 Ttl Unit

USER MANUAL GEBRAUCHSANLEITUNG MANUEL D’UTILISATION EN MANUALE D’USO FR MANUAL DE FUNCIONAMIENTO ES MANUAL DO USUÁRIO IT GEBRUIKSAANWIJZING NL РУКОВОДСТВО ПО ЭКСПЛУАТАЦИИ DE PT ユーザーマニュアル 用户手册 ELB 500 TTL UNIT Elinchrom LTD – ELB 500 TTL Unit – 11.2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 ELB 500 TTL CHARACTERISTICS 5 BEFORE YOU START 7 GENERAL USER SAFETY INFORMATION 7 CONTROL PANEL 12 MENU FEATURES 19 RADIO FEATURES & SETUP 19 EN SKYPORT MODE 20 PHOTTIX MODE 20 FLASH MODE SETUP 21 ELB 500 BATTERY 23 ELB 500 HEAD 27 TROUBLESHOOTING 29 MAINTENANCE 31 DISPOSAL AND REYCLING 33 TECHNICAL DATA 34 LEGAL INFORMATION 36 DECLARATION OF CONFORMITYUSA & CANADA 39 3 INTRODUCTION Dear photographer, Thank you for buying the Elinchrom ELB 500 TTL unit. All Elinchrom products are manufactured using the most advanced technology. Carefully selected components are used to ensure the highest quality and the equipment is submitted to many tests both during and after manufacture. We trust that it will give you many years of reliable service. Please read the instructions carefully before use, for your safety and to obtain maximum benefit from many features. Your Elinchrom-Team EN This manual may show images of products with accessories, which are not part of sets or single units. Elinchrom set and single unit configurations may change without advice and may differ in other countries. Please find actual configurations at www.elinchrom.com For further details, upgrades, news and the latest information about the Elinchrom System, please regularly visit the Elinchrom website. The latest user guides and technical specifications can be downloaded in the “Support” area. -

Order of Battle Changes for Operation Phantom Thunder

BACKGROUNDER #2 Order of Battle for Operation Phantom Thunder Kimberly Kagan, Executive Director and Wesley Morgan, Researcher June 20, 2007 General David Petraeus, commander of Multi-National Forces-Iraq, and Lieutenant General Raymond Odierno, commander of Multi-National Corps-Iraq, launched a coordinated offensive operation on June 15, 2007 to clear al Qaeda strongholds outside of Baghdad. The arrival of the fifth Army “surge” brigade, the Marine Expeditionary Unit, and the combat aviation brigade enabled GEN Petraeus and LTG Odierno to begin this major offensive, named “Operation Phantom Thunder.” Three different U.S. Division Headquarters in different provinces are participating in Phantom Thunder. Multi-National Division-North (Diyala); Multi-National Division-Center (North Babil and Baghdad); and Multi-National Division-West (Anbar). In addition to reinforcing these areas with new troops, LTG Odierno and his division commanders have repositioned some brigades and battalions that were already operating in and around Baghdad. MND-North, Diyala Operation Arrowhead Ripper The core unit in Diyala has been 3rd BCT (Brigade Combat Team), 1st Cavalry Division, which has four battalions plus reinforcements. One of its battalions, 1-12 CAV, has been stationed on FOB Warhorse. A second battalion from the same brigade, the 6-9 ARS, has been operating in Muqdadiya, northeast of Baquba. The 5-73 RSTA (Reconnaissance, Scouting, and Target Acquisition Squadron) has been operating in the river valley northeast of Baquba (in locations such as Zaganiyah). The 5-20 Infantry has been operating in and around southern Baquba. (In addition, MND-N has sent a company from 2-35 Infantry to 5-73 and a company from 1-505 Parachute Infantry Regiment to 6-9 in order to provide those battalions with infantry). -

Copyrighted Material

Studio & Location Lighting Secrets Index Numerics Dodge tool, 150–151 1D Mark III, 102 Elliptical tool, 153 5D Mark II, 75, 104, 119, 120 enhancing details, 158–159 5k movie light, 110 Exposure, Layer panel, 163 17-40mm lens, 75 Flashlight fi lter, 139 24mm lens, 8 framing, 150–151 24-105mm lens, 11–12, 15, 104 F-Stop, changing, 142–143 28-75mm Di lens, 99 gray spotlight, 141 50mm lens, 8, 142, 143 Healing Brush tool, 51, 139 55mm lens, 110 high-fashion stylized look, 148–149 70-200mm lens, 102–103, 119–120, 126 Hue/Saturation, 118 85mm lens, 8, 94, 142 lens, changing, 142–143 105mm lens, 142 Levels panel, 36 135mm lens, 8 Light Types, 141 200mm lens, 8 Lighting Eff ects fi lter, 141 550 EX fl ash, 89 Magic Wand tool, 124 movie-star-style lighting, 162–163 A MZ Soft Focus fi lter, 103 accent light, 120 Omni light, 140–141 Adaptive Exposure setting, Topaz Adjust orange spotlight, 141 plug-in, 159 overview, 138–139 adaptor ring, 4 post-processing, 88 Adjustment layer, Photoshop Quick Selection tool, 143 black and white, 144–145 Radial Blur fi lter, 160–161 image saturation, 139 Rectangular Marquee tool, 163 Adobe Photoshop refl ections, 26 Adjustment layer, 139 Render Lighting Eff ects, 140 anchor points, Preview window, 141 Sepia Action fi lter, 77 artistic eff ects, 156–157 Shadow/Highlight, 118 black and white background, 115 Spotlight option, 140–141 black and white images, 144–147 Surface Blur tool, 117, 135 Burn tool, 114 COPYRIGHTED Totally MATERIAL Rad Mega Mix actions, 126 burned edges, 93 Triangle Treat factor setting, 143 Clone -

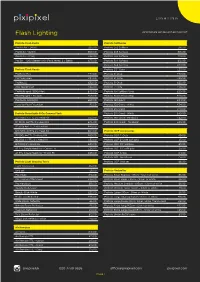

Flash Lighting All Prices Are Per Day and Exclude VAT

LIGHTING Flash Lighting All prices are per day and exclude VAT Profoto Flash Packs Profoto Softboxes Pro-10 Air – 2400j £65.00 Profoto 2x2 Softbox £16.00 Pro-8 Air – 2400j £60.00 Profoto 2x3 Softbox £16.00 Pro-8 Air – 1200j £46.00 Profoto 3x3 Softbox £18.00 Pro B4 – 1000j Battery Kit (Pack, Head, 2 x Batts) £75.00 Profoto 3x4 Softbox £18.00 Profoto 6x4 Softbox £22.00 Profoto Flash Heads Profoto 2'3” Octa £23.00 ProHead Plus £22.00 Profoto 3' Octa £23.00 ProTwin Head £34.00 Profoto 4' Octa £25.00 ProRing 2 £32.00 Profoto 5' Octa £28.00 ProFresnel Spot £44.00 Profoto 7’ Octa £36.00 ProMulti spot (1200j Max) £40.00 Profoto 4x1 Softbox Strip £20.00 ProStriplight – Medium £56.00 Profoto 6x1 Softbox Strip £20.00 ProZoom Spotlight £60.00 Profoto 150 Giant £34.00 Head to Pack Extension £8.00 Profoto 150 Giant - White £34.00 Profoto 210 Giant £40.00 Profoto Monolights & On Camera Flash Profoto 210 Giant - White £40.00 D2 1000j AirTTL 2 x Head Kit £54.00 Profoto 180 Giant - Parabolic £42.00 D1 1000j AirTTL 2 x Head Kit £46.00 Profoto 240 Giant - Parabolic £55.00 D1 500j AirTTL 2 x Head Kit £40.00 B1X 500j AirTTL 2 x Head Kit £64.00 Profoto OCF Accessories B1 500j AirTTL 2 x Head Kit £60.00 Profoto OCF 2’ Octa £9.00 B2 250j AirTTL 2 x Head Kit £52.00 Profoto OCF 2’ Octa soft grid £5.00 B10 250j 2 x Head Kit £55.00 Profoto OCF 1‘3” Softbox £9.00 A1 TTL Single Head Kit – Canon Fit £28.00 Profoto OCF 1‘3” soft grid £5.00 A1 TTL Single Head Kit – Nikon Fit £28.00 Profoto OCF Snoot £4.00 Profoto OCF Barndoors £4.00 Profoto Light Shaping Tools Profoto -

Photography in Lancaster

The Art o/ Photography in Lancaster By M. LATHER HEISEY HEN Robert Burns said: "0 wod some Pow'r the giftie gie W us, to see oursels as ithers see us !" he did not realize that one answer to his observation would be given to the world by the invention of photography. Until that time men saw their images "as through a glass darkly," by the medium of skillfully painted portraits by the old masters, by reflections in mirrors, placid streams or highly polished surfaces. Years before 1839, artists and chemists had been experiment- ing with methods to retain a permanent image or reflection of an object upon a canvass or other surface. In August of that year photography "came to light" when Louis J. M. Daguerre (1789- 1851) first publicly announced his process in Paris. "Daguerre, a French painter of dioramas, astonished the scientific world by pro- ducing sun pictures obtained by exposing the surface of a highly polished silver tablet to the vapor of iodine in a dark room, and then placing the tablet in a camera obscuro, and exposing it to the sunlight. A latent image of the object within the range of the camera was thus obtained, and this image was developed by expos- ing the tablet to the fumes of mercury, heated to a temperature of about 170° Fahrenheit. The image thus secured was 'fixed' or made permanent by dipping the tablet into a solution of hyposul- phite of soda, and then carefully washing and drying the plate." 1 The development of photography to the perfection of the pres- ent time was, like all inventions, a slow and steady advance.