The Development and Growth of British Photographic Manufacturing and Retailing 1839-1914

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art of Victorian Photography

THE ART OF VICTORIAN Dr. Laurence Shafe [email protected] PHOTOGRAPHY www.shafe.uk The Art of Victorian Photography The invention and blossoming of photography coincided with the Victorian era and photography had an enormous influence on how Victorians saw the world. We will see how photography developed and how it raised issues concerning its role and purpose and questions about whether it was an art. The photographic revolution put portrait painters out of business and created a new form of portraiture. Many photographers tried various methods and techniques to show it was an art in its own right. It changed the way we see the world and brought the inaccessible, exotic and erotic into the home. It enabled historic events, famous people and exotic places to be seen for the first time and the century ended with the first moving images which ushered in a whole new form of entertainment. • My aim is to take you on a journey from the beginning of photography to the end of the nineteenth century with a focus on the impact it had on the visual arts. • I focus on England and English photographers and I take this title narrowly in the sense of photographs displayed as works of fine art and broadly as the skill of taking photographs using this new medium. • In particular, • Pre-photographic reproduction (including drawing and painting) • The discovery of photography, the first person captured, Fox Talbot and The Pencil of Light • But was it an art, how photographers created ‘artistic’ photographs, ‘artistic’ scenes, blurring, the Pastoral • The Victorian -

Each Wild Idea: Writing, Photography, History

e “Unruly, energetic, unmastered. Also erudite, engaged and rigorous. Batchen’s essays have arrived at exactly the e a c h w i l d i d e a right moment, when we need their skepticism and imagination to clarify the blurry visual thinking of our con- a writing photography history temporary cultures.” geoffrey batchen c —Ross Gibson, Creative Director, Australian Centre for the Moving Image h In Each Wild Idea, Geoffrey Batchen explores widely ranging “In this remarkable book, Geoffrey Batchen picks up some of the threads of modernity entangled and ruptured aspects of photography, from the timing of photography’s by the impact of digitization and weaves a compelling new tapestry. Blending conceptual originality, critical invention to the various implications of cyberculture. Along w insight and historical rigor, these essays demand the attention of all those concerned with photography in par- the way, he reflects on contemporary art photography, the role ticular and visual culture in general.” i of the vernacular in photography’s history, and the —Nicholas Mirzoeff, Art History and Comparative Studies, SUNY Stony Brook l Australianness of Australian photography. “Geoffrey Batchen is one of the few photography critics equally adept at historical investigation and philosophi- d The essays all focus on a consideration of specific pho- cal analysis. His wide-ranging essays are always insightful and rewarding.” tographs—from a humble combination of baby photos and —Mary Warner Marien, Department of Fine Arts, Syracuse University i bronzed booties to a masterwork by Alfred Stieglitz. Although d Batchen views each photograph within the context of broader “This book includes the most important essays by Geoffrey Batchen and therefore is a must-have for every schol- social and political forces, he also engages its own distinctive ar in the fields of photographic history and theory. -

Festschrift:Experimenting with Research: Kenneth Mees, Eastman

Science Museum Group Journal Festschrift: experimenting with research: Kenneth Mees, Eastman Kodak and the challenges of diversification Journal ISSN number: 2054-5770 This article was written by Jeffrey Sturchio 04-08-2020 Cite as 10.15180; 201311 Research Festschrift: experimenting with research: Kenneth Mees, Eastman Kodak and the challenges of diversification Published in Spring 2020, Issue 13 Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201311 Abstract Early industrial research laboratories were closely tied to the needs of business, a point that emerges strikingly in the case of Eastman Kodak, where the principles laid down by George Eastman and Kenneth Mees before the First World War continued to govern research until well after the Second World War. But industrial research is also a gamble involving decisions over which projects should be pursued and which should be dropped. Ultimately Kodak evolved a conservative management culture, one that responded sluggishly to new opportunities and failed to adapt rapidly enough to market realities. In a classic case of the ‘innovator’s dilemma’, Kodak continued to bet on its dominance in an increasingly outmoded technology, with disastrous consequences. Component DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201311/001 Keywords Industrial R&D, Eastman Kodak Research Laboratories, Eastman Kodak Company, George Eastman, Charles Edward Kenneth Mees, Carl Duisberg, silver halide photography, digital photography, Xerox, Polaroid, Robert Bud Author's note This paper is based on a study undertaken in 1985 for the R&D Pioneers Conference at the Hagley Museum and Library in Wilmington, Delaware (see footnote 1), which has remained unpublished until now. I thank David Hounshell for the invitation to contribute to the conference and my fellow conferees and colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania for many informative and stimulating conversations about the history of industrial research. -

Download PDF Version

100 Books With Original Photographs 1846–1919 PAUL M. HERTZMANN, INC. MARGOLIS & MOSS 100 BOOKS With ORIGINAL PHOTOGRAPHS 1846–1919 PAUL M. HERTZMANN, INC. MARGOLIS & MOSS Paul M. Hertzmann & Susan Herzig David Margolis & Jean Moss Post Office Box 40447 Post Office Box 2042 San Francisco, California 94140 Santa Fe, New Mexico 87504-2042 Tel: (415) 626-2677 Fax: (415) 552-4160 Tel: (505) 982-1028 Fax: (505) 982-3256 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Association of International Photography Art Dealers Antiquarian Booksellers’Association of America Private Art Dealers Association International League of Antiquarian Booksellers 90. TERMS The books are offered subject to prior sale. Customers will be billed for shipping and insurance at cost. Payment is by check, wire transfer, or bank draft. Institutions will be billed to suit their needs. Overseas orders will be sent by air service, insured. Payment from abroad may be made with a check drawn on a U. S. bank, international money order, or direct deposit to our bank account. Items may be returned within 5 days of receipt, provided prior notification has been given. Material must be returned to us in the same manner as it was sent and received by us in the same condition. Inquiries may be addressed to either Paul Hertzmann, Inc. or Margolis & Moss Front cover and title page illustrations: Book no. 82. 2 introduction his catalog, a collaborative effort by Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc., and Margolis & Moss, T reflects our shared passion for the printed word and the photographic -

Della Fotografia “Istantanea” 1839-1865

DELLA FOTOGRAFIA “ISTANTANEA” 1839-1865 Giovanni Fanelli 2020 DELLA FOTOGRAFIA “ISTANTANEA” 1839-1865 Giovanni Fanelli 2020 L’arte ha aspirato spesso alla rappresentazione del movimento. Leonardo da Vinci fu maestro nello studio dell’ottica, della luce, del movimento e nella raffigurazione della istantaneità nei fenommeni naturali e nella vita degli esseri viventi. E anche l’arte del ritratto era per lui cogliere il movimento dell’emozione interiore. * La fotografia, per natura oggetto e bidimensionale, non può a rigor di termini riprodurre il movimento come in un certo modo può fare il cinema; può soltanto, se il fotografo ne ha l’intenzione, riprenderne un istante che nella sua fugacità riassuma la mobilità. Tuttavia fin dall’inizio della storia della fotografia i fotografi aspirarono a riprendere il movimento. Già Daguerre o Talbot aspiravano alla istantaneità. Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre, Paris, Boulevard du Temple alle 8 del mattino, fine aprile 1838, dagherrotipo, 12,9x16,3, Munich, Fotomuseum im mûnchner Stadtmuseum. Henry Fox Talbot, Eliza Freyland con in braccio Charles Henry Talbot, con Eva e Rosamond Talbot, 5 aprile 1842, stampa su carta salata da calotipo, 18,8x22,5. Bradford, The National Museum of Photography, Film & Television. Una delle prime immagini fotografiche, il dagherrotipo della veduta ripresa da Daguerre dall’alto del suo Diorama è animata : all’angolo del boulevard du Temple è presente un uomo immobile il tempo di farsi lucidare le scarpe. Le altre persone che certamente a quell’ora animavano il boulevard non appaiono perché il tempo di posa del dagherotipo era lungo (calcolabile a circa 7 minuti) (cfr. Jacques Roquencourt http://www.niepce-daguerre.com/ ). -

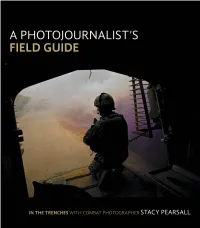

A Photojournalist's Field Guide: in the Trenches with Combat Photographer

A PHOTOJOURNALISt’S FIELD GUIDE IN THE TRENCHES WITH COMBAT PHOTOGRAPHER STACY PEARSALL A Photojournalist’s Field Guide: In the trenches with combat photographer Stacy Pearsall Stacy Pearsall Peachpit Press www.peachpit.com To report errors, please send a note to [email protected] Peachpit Press is a division of Pearson Education. Copyright © 2013 by Stacy Pearsall Project Editor: Valerie Witte Production Editor: Katerina Malone Copyeditor: Liz Welch Proofreader: Erin Heath Composition: WolfsonDesign Indexer: Valerie Haynes Perry Cover Photo: Stacy Pearsall Cover and Interior Design: Mimi Heft Notice of Rights All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or trans- mitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy- ing, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For information on getting permission for reprints and excerpts, contact [email protected]. Notice of Liability The information in this book is distributed on an “As Is” basis, without warranty. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of the book, neither the author nor Peachpit shall have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the instructions contained in this book or by the computer software and hardware products described in it. Trademarks Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and Peachpit was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations appear as requested by the owner of the trademark. -

Photography: a Survey of New Reference Sources

RSR: Reference Services Review. 1987, v.15, p. 47 -54. ISSN: 0090-7324 Weblink to journal. ©1987 Pierian Press Current Surveys Sara K. Weissman, Column Editor Photography: A Survey of New Reference Sources Eleanor S. Block What a difference a few years make! In the fall 1982 issue of Reference Services Review I described forty reference monographs and serial publications on photography. That article concluded with these words, "a careful reader will be aware that not one single encyclopedia or solely biographical source was included... this reviewer could find none in print... A biographical source proved equally elusive" (p.28). Thankfully this statement is no longer valid. Photography reference is greatly advanced and benefited by a number of fine biographical works and a good encyclopedia published in the past two or three years. Most of the materials chosen for this update, as well as those cited in the initial survey article, emphasize the aesthetic nature of photography rather than its scientific or technological facets. A great number of the forty titles in the original article are still in print; others have been updated. Most are as valuable now as they were then for good photography reference selection. However, only those sources published since 1982 or those that were not cited in the original survey have been included. This survey is divided into six sections: Biographies, Dictionaries (Encyclopedias), Bibliographies, Directories, Catalogs, and Indexes. BIOGRAPHIES Three of the reference works cited in this survey have filled such a lamented void in photography reference literature that they stand above the rest in their importance and value. -

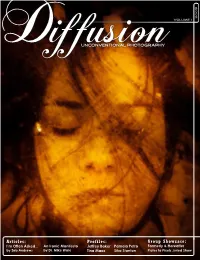

Download the Free Pdf of Volume I

9 volume 1 200 DiffusionUnconventional Photography Articles: Profiles: Group Showcase: I’m Often Asked... An Ironic Manifesto Jeffrey Baker Pamela Petro Formerly & Hereafter by Zeb Andrews by Dr. Mike Ware Tina Maas Sika Stanton Plates to Pixels Juried Show Praise for Diffusion, Volume I “Avant-garde, breakthrough and innovative are just three adjectives that describe editor Blue Mitchell’s first foray into the world of fine art photography magazines. Diffusion magazine, tagged as unconventional photography delivers on just that. Volume 1 features the work of Jeffrey Baker, Pamela Petro, Tina Maas and Sika Stanton. With each artist giving you a glimpse into how photography forms an integral part of each of their creative journey. The first issue’s content is rounded out by Zeb Andrews’ and Dr. Mike Ware. Zeb Andrews’ peak through his pin-hole world is complimented by an array of his creations along with the 900 second exposure “Fun Center” as the show piece. And Dr. Mike unscrambles the history of iron-based photographic processes and the importance of the printmaker in the development of a fine art image. At a time when we are seeing a mass migration to on-line publishing and on-line magazine hosting, the editorial team at Diffusion proves you can still deliver an outstanding hard-copy fine art photography magazine. I consumed my copy immediately with delight; now when is the next issue coming out?” - Michael Van der Tol “Regardless of the retrospective approach to the medium of photography, which could be perceived by many as a conservative drive towards nostalgia and sentimentality. -

Negative Kept

[ THIS PAGE ] Batt and Richards (fl . 1867-1874). Maori Fisherman. Verso with inscribed title and photographers’ imprint. Albumen print, actual size. [ ENDPAPERS ] Thomas Price (fl . c. 1867-1920s). Collage of portraits, rephotographed in a carved wood frame, c. 1890. Gelatin silver print, 214 by 276 mm. [ COVER ] Portrait, c. 1870. Albumen print, actual size. Negative kept Negative In memoryofRogerNeichandJudithBinney Maori andthe John Leech Gallery, Auckland,2011 John LeechGallery, Introductory essayIntroductory byKeith Giles Michael Graham-Stewart in association with in association John Gow carte devisite _ 004 Preface Photography was invented, or at least entered the public sphere, in France and England in 1839 with the near simultaneous announcements of the daguerreotype and photogenic drawing techniques. The new medium was to have as great an infl uence on humankind and the transmission of history as had the written and printed word. Visual, as well as verbal memory could now be fi xed and controlled; our relationship with time forever altered. However, unlike text, photography experienced a rapid mutation through a series of formats in the 19th century culminating in fi lm, a sequence of stopped motion images. But even as this latest incarnation spread, earlier forms persisted: stereographs, cabinet cards and what concerns us here, the carte de visite. Available from the late 1850s, this small and tactile format rapidly expanded the reach of photography away from just the wealthy. In the words of the Sydney Morning Herald of 5 May 1859: Truly this is producing portraits for the million (the entire population of white Australia). Seeing and handling a carte would have been most New Zealanders’ fi rst photographic experience. -

British Art Studies November 2020 British Art Studies Issue 18, Published 30 November 2020

British Art Studies November 2020 British Art Studies Issue 18, published 30 November 2020 Cover image: Sonia E. Barrett, Table No. 6, 2013, wood and metal.. Digital image courtesy of Bruno Weiss. PDF generated on 21 July 2021 Note: British Art Studies is a digital publication and intended to be experienced online and referenced digitally. PDFs are provided for ease of reading offline. Please do not reference the PDF in academic citations: we recommend the use of DOIs (digital object identifiers) provided within the online article. Theseunique alphanumeric strings identify content and provide a persistent link to a location on the internet. A DOI is guaranteed never to change, so you can use it to link permanently to electronic documents with confidence. Published by: Paul Mellon Centre 16 Bedford Square London, WC1B 3JA https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk In partnership with: Yale Center for British Art 1080 Chapel Street New Haven, Connecticut https://britishart.yale.edu ISSN: 2058-5462 DOI: 10.17658/issn.2058-5462 URL: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk Editorial team: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/editorial-team Advisory board: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/advisory-board Produced in the United Kingdom. A joint publication by Contents Making a Case: Daguerreotypes, Steve Edwards Making a Case: Daguerreotypes Steve Edwards Abstract This essay considers physical daguerreotype cases from the 1840s and 1850s alongside scholarly debate on case studies, or “thinking in cases”, and some recent physicalist claims about objects in cultural theory, particularly those associated with “new materialism”. Throughout the essay, these three distinct strands are braided together to interrogate particular objects and broader questions of cultural history. -

The Treaty of Nanking: Form and the Foreign Office, 1842–43

The Treaty of Nanking: Form and the Foreign Office, 1842–43 R. DEREK WOOD [Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, May 1996, Vol. 24 (2), pp. 181-196] First witness (1841): Captain Charles Elliot, as Superintendant of the British Trade mission to China, had an important meeting with the Chinese Imperial Commissioner Ch’i–shan on 27 January1841: I placed in his hands a Chinese version of the Treaty. He examined it with deep attention and evident distress, observing that great as the difficulties were in point of substance, he did not believe they would be as insuperable as those of form.1,2 Second witness (1842): an anonymous contributor to a German newspaper describes how he had an opportunity in the quiet of Christmas day 1842 of seeing ‘one of the most important documents of modern times’ at the Foreign Office in London: On my asking for the room where was working Mr. Collins [sic. Collen] ... I was directed towards the Attic. I had many stairs to climb, meeting nobody, nor could I hear any human sound. In this way I passed by a printing machine workshop; for this world–office is itself a small world containing everything it needs to be effective. Above this, in a small room with closed shutters, I found Mr. Collins, who with the help of an assistant was busy by means of lights copying the Treaty. The document itself is of Strawpaper, 4 foot long and about 10 inches wide; the letters are daintily painted figures and it has three elongated woodblock impressions in red ink as seals of authority. -

KODAK MILESTONES 1879 - Eastman Invented an Emulsion-Coating Machine Which Enabled Him to Mass- Produce Photographic Dry Plates

KODAK MILESTONES 1879 - Eastman invented an emulsion-coating machine which enabled him to mass- produce photographic dry plates. 1880 - Eastman began commercial production of dry plates in a rented loft of a building in Rochester, N.Y. 1881 - In January, Eastman and Henry A. Strong (a family friend and buggy-whip manufacturer) formed a partnership known as the Eastman Dry Plate Company. ♦ In September, Eastman quit his job as a bank clerk to devote his full time to the business. 1883 - The Eastman Dry Plate Company completed transfer of operations to a four- story building at what is now 343 State Street, Rochester, NY, the company's worldwide headquarters. 1884 - The business was changed from a partnership to a $200,000 corporation with 14 shareowners when the Eastman Dry Plate and Film Company was formed. ♦ EASTMAN Negative Paper was introduced. ♦ Eastman and William H. Walker, an associate, invented a roll holder for negative papers. 1885 - EASTMAN American Film was introduced - the first transparent photographic "film" as we know it today. ♦ The company opened a wholesale office in London, England. 1886 - George Eastman became one of the first American industrialists to employ a full- time research scientist to aid in the commercialization of a flexible, transparent film base. 1888 - The name "Kodak" was born and the KODAK camera was placed on the market, with the slogan, "You press the button - we do the rest." This was the birth of snapshot photography, as millions of amateur picture-takers know it today. 1889 - The first commercial transparent roll film, perfected by Eastman and his research chemist, was put on the market.