Negative Kept

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Services

North King Country Orientation Package Community Services Accommodation Real Estate Provide advice on rental and purchasing of real estate. Bruce Spurdle First National Real Estate. 18 Hinerangi St, Te Kuiti. 027 285 7306 Century 21 Countrywide Real Estate. 131 Rora St, Te Kuiti. 07 878 8266 Century 21 Countrywide Real Estate. 45 Maniapoto St, Otorohanga. 07 873 6083 Gold 'n' Kiwi Realty. 07 8737494 Harcourts. 130 Maniapoto St, Otorohanga 07 873 8700 Harcourts. 69 Rora St, Te Kuiti. 07 878 8700 Waipa Property Link. K!whia 07 871 0057 Information about property sales and rental prices Realestate.co.nz, the official website of the New Zealand real estate industry http://www.realestate.co.nz/ Terralink International Limited http://www.terranet.co.nz/ Quotable Value Limited (QV) http://www.qv.co.nz/ Commercial Accommodation Providers Abseil Inn Bed & Breakfast. Waitomo Caves Rd. Waitomo Caves 07 878 7815 Angus House Homestay/ B & B. 63 Mountain View Rd. Otorohanga 07 873 8955 Awakino Hotel. Main Rd. M"kau 06 752 9815 Benneydale Hotel. Ellis Rd. Benneydale 07 878 4708 Blue Chook Inn. Jervois St. K!whia 07 871 0778 Carmel Farm Stay. Main Rd. Piopio 07 877 8130 Casara Mesa Backpackers. Mangarino Rd. Te Kuiti 07 878 6697 Caves Motor Inn. 728 State Highway 3. Hangatiki Junction. Waitomo 07 873 8109 Churstain Bed & Breakfast. 129 Gadsby Rd. Te Kuiti 07 878 8191 Farm Bach Mahoenui. RD, Mahoenui 07 877 8406 Glow Worm Motel. Corner Waitomo Caves Rd. Hangatiki 07 873 8882 May 2009 Page 51 North King Country Orientation Package Juno Hall Backpackers. -

Contact Sheet

CONTACT SHEET The personal passions and public causes of Prince Albert, husband of Queen Victoria, are revealed, as photographs, prints and letters are published online today to mark the 200th anniversary of his birth After Roger Fenton, Prince Albert, May 1854, 1889 copy of the original Queen Victoria commissioned a set of private family photographs to be taken by Roger Fenton at Buckingham Palace in May 1854, including a portrait of Albert gazing purposefully at the camera, his legs crossed, in front of a temporary backdrop that had been created. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert In a letter beginning ‘My dearest cousin’, written in June 1837, Albert congratulates Victoria on becoming Queen of England, wishing her reign to be long, happy and glorious. Royal Archives / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019 Queen Victoria kept volumes of reminiscences between 1840 and 1861. In these pages she describes how Prince Albert played with his young children, putting a napkin around their waist and swinging them backwards and forwards between his legs. The Queen also sketched the scenario (left) Royal Archives / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019 Press Office, Royal Collection Trust, York House, St James’s Palace, London SW1A 1BQ T. +44 (0)20 7839 1377, [email protected], www.rct.uk After Franz Xaver Winterhalter, Bracelet with photographs of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert’s nine children, 1854–7 This bracelet was given to Queen Victoria by Prince Albert for her birthday on 24 May 1854. John Jabez Edwin Mayall, Frame with a photograph of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, 1860 In John Jabez Edwin Mayall’s portrait of 1860, the Queen stands dutifully at her seated husband’s side, her head bowed. -

Whanganui Ki Maniapoto

'. " Wai 903, #A 11 OFFICIAL WAI48 Preliminary Historical Report Wai 48 and related claims Whanganui ki Maniapoto \ Alan Ward March 1992 "./-- · TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. I THE NA TURE OF THE CLAIMS AND GENERAL HISTORICAL BA CKGROUND ...................... 9 1. The claims . .. 9 2. The oreliminarv report . .. 10 3. The iwi mainlv affected . .. 10 4. Early contacts with Europeans ................. 12 5. The Treaty of Waitangi ...................... 13 6. Early Land Acquisitions: .................. , . .. 15 7. Underlving Settler Attitudes . .. 16 8. Government land ourchase policy after 1865 ....... 18 fl. WHANGANUI AND THE MURIMOTU ................ 20 1. Divisions over land and attempts to contain them ... 20 2. Sales proceed . ........................... 22 /------, 3. Murimotu .. .................•............ 23 -1< ____)' 4. Strong trading in land? ...................... 25 5. Dealings over Murimotu-Rangipo ............... 26 6. Further attempts to limit land selling ............ 27 7. Kemp's Trust . 29 Iff THE KING COUNTRY ........... .. 30 1. Increasing contacts with government. .. 30 2. The Rotorua model ......................... 33 3. Whatiwhatihoe, May 1882: origins of the Rohe Potae concep t . , . .. , , , . , , . , , . 33 4. Government policy ., ....................... 36 5. Legislative preparations ........ , . , ...... , , , . 36 6. The Murimotu legislation .......... , .. ,....... 37 7. The Mokau-Mohakatino .. , ............. , , ... , 38 - 2 - 8. Maungatautari. • . • . • . • • . • . • • . 39 ) 9. Native Committees, 1883 -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

British Art Studies November 2020 British Art Studies Issue 18, Published 30 November 2020

British Art Studies November 2020 British Art Studies Issue 18, published 30 November 2020 Cover image: Sonia E. Barrett, Table No. 6, 2013, wood and metal.. Digital image courtesy of Bruno Weiss. PDF generated on 21 July 2021 Note: British Art Studies is a digital publication and intended to be experienced online and referenced digitally. PDFs are provided for ease of reading offline. Please do not reference the PDF in academic citations: we recommend the use of DOIs (digital object identifiers) provided within the online article. Theseunique alphanumeric strings identify content and provide a persistent link to a location on the internet. A DOI is guaranteed never to change, so you can use it to link permanently to electronic documents with confidence. Published by: Paul Mellon Centre 16 Bedford Square London, WC1B 3JA https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk In partnership with: Yale Center for British Art 1080 Chapel Street New Haven, Connecticut https://britishart.yale.edu ISSN: 2058-5462 DOI: 10.17658/issn.2058-5462 URL: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk Editorial team: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/editorial-team Advisory board: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/advisory-board Produced in the United Kingdom. A joint publication by Contents Making a Case: Daguerreotypes, Steve Edwards Making a Case: Daguerreotypes Steve Edwards Abstract This essay considers physical daguerreotype cases from the 1840s and 1850s alongside scholarly debate on case studies, or “thinking in cases”, and some recent physicalist claims about objects in cultural theory, particularly those associated with “new materialism”. Throughout the essay, these three distinct strands are braided together to interrogate particular objects and broader questions of cultural history. -

The Development and Growth of British Photographic Manufacturing and Retailing 1839-1914

The development and growth of British photographic manufacturing and retailing 1839-1914 Michael Pritchard Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Imaging and Communication Design Faculty of Art and Design De Montfort University Leicester, UK March 2010 Abstract This study presents a new perspective on British photography through an examination of the manufacturing and retailing of photographic equipment and sensitised materials between 1839 and 1914. This is contextualised around the demand for photography from studio photographers, amateurs and the snapshotter. It notes that an understanding of the photographic image cannot be achieved without this as it directly affected how, why and by whom photographs were made. Individual chapters examine how the manufacturing and retailing of photographic goods was initiated by philosophical instrument makers, opticians and chemists from 1839 to the early 1850s; the growth of specialised photographic manufacturers and retailers; and the dramatic expansion in their number in response to the demands of a mass market for photography from the late1870s. The research discusses the role of technological change within photography and the size of the market. It identifies the late 1880s to early 1900s as the key period when new methods of marketing and retailing photographic goods were introduced to target growing numbers of snapshotters. Particular attention is paid to the role of Kodak in Britain from 1885 as a manufacturer and retailer. A substantial body of newly discovered data is presented in a chronological narrative. In the absence of any substantive prior work this thesis adopts an empirical approach firmly rooted in the photographic periodicals and primary sources of the period. -

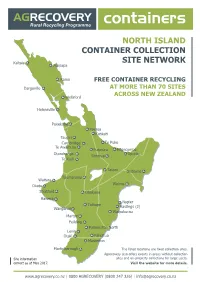

North Island Container Collection Site Network

NORTH ISLAND CONTAINER COLLECTION Kaitaia SITE NETWORK Waipapa Kamo FREE CONTAINER RECYCLING Dargaville AT MORE THAN 70 SITES ACROSS NEW ZEALAND Wellsford Helensville Pukekohe Paeroa Katikati Taupiri Cambridge Te Puke Te Awamutu Putaruru Edgecumbe Otorohanga Opotiki Rotorua Te Kuiti Taupo Gisborne Taumarunui Waitara Wairoa Okato Stratford Ohakune Hawera Napier Taihape Hastings (2) Wanganui Waipukurau Marton Feilding Palmerston North Levin Otaki Pahiatua Masterton Martinborough The listed locations are fixed collection sites. Agrecovery also offers events in areas without collection Site information sites and on-property collections for large users. correct as at May 2017. Visit the website for more details. www.agrecovery.co.nz | 0800 AGRECOVERY (0800 247 326) | [email protected] North Island Collection Sites Address Opening Hours NORTHLAND Dargaville Farmlands 1 River Road Monday to Friday 8:30am - 4pm Kaitaia Farmlands 31 North Park Drive Monday to Friday 8:30am - 4pm Kamo Farmlands 2 Springs Flat Road Monday to Friday 8am - 5pm Waipapa PGG Wrightson Cnr State Highway 10 & Pataka Lane Monday to Friday 8am - 5pm AUCKLAND Helensville Helensville Community 31 Mill Road Thursday to Sunday 8am - 4pm Recycling Centre Pukekohe Farmlands 86A Harris Street Monday to Friday 8am - 5pm Wellsford Farmlands 113 Centennial Park Road Monday to Friday 8am - 5pm Waiheke Island Contact Steve Sherson of Fruitfed Supplies on 027 479 7338 WAIKATO Cambridge Farmlands Hautapu 64 Hautapu Road Monday to Friday 8am - 5pm Otorohanga VETFOCUS 9 Wahanui Crescent -

Aspects of Rohe Potae Political Engagement, 1886 to 1913

OFFICIAL Wai 898 #A71 Aspects of Rohe Potae Political Engagement, 1886 to 1913 Dr Helen Robinson and Dr Paul Christoffel A report commissioned by the Waitangi Tribunal for the Te Rohe Potae (Wai 898) district inquiry August 2011 RECEIVED Waitangi Tribunal 31 Aug 2011 Ministry of Justice WELLINGTON Authors Dr Paul John Christoffel has been a Research Analyst/Inquiry Facilitator at the Waitangi Tribunal Unit since December 2006. He has a PhD in New Zealand history from Victoria University of Wellington and 18 years experience in policy and research in various government departments. His previous report for the Tribunal was entitled ‘The Provision of Education Services to Maori in Te Rohe Potae, 1840 – 2010’ (Wai 898, document A27). Dr Helen Robinson has been a Research Analyst/Inquiry Facilitator at the Waitangi Tribunal Unit since April 2009 and has a PhD in history from the University of Auckland. She has published articles in academic journals in New Zealand and overseas, the most recent being ‘Simple Nullity or Birth of Law and Order? The Treaty of Waitangi in Legal and Historiographical Discourse from 1877 to 1970’ in the December 2010 issue of the New Zealand Universities Law Review. Her previous report for the Tribunal was ‘Te Taha Tinana: Maori Health and the Crown in Te Rohe Potae Inquiry District, 1840 to 1990’ (Wai 898, document A31). i Contents Authors i Contents ii List of maps v List of graphs v List of figures v Introduction 1 The approach taken 2 Chapter structure 3 Claims and sources 4 A note on geographical terminology -

The Techniques and Material Aesthetics of the Daguerreotype

The Techniques and Material Aesthetics of the Daguerreotype Michael A. Robinson Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Photographic History Photographic History Research Centre De Montfort University Leicester Supervisors: Dr. Kelley Wilder and Stephen Brown March 2017 Robinson: The Techniques and Material Aesthetics of the Daguerreotype For Grania Grace ii Robinson: The Techniques and Material Aesthetics of the Daguerreotype Abstract This thesis explains why daguerreotypes look the way they do. It does this by retracing the pathway of discovery and innovation described in historical accounts, and combining this historical research with artisanal, tacit, and causal knowledge gained from synthesizing new daguerreotypes in the laboratory. Admired for its astonishing clarity and holographic tones, each daguerreotype contains a unique material story about the process of its creation. Clues from the historical record that report improvements in the art are tested in practice to explicitly understand the cause for effects described in texts and observed in historic images. This approach raises awareness of the materiality of the daguerreotype as an image, and the materiality of the daguerreotype as a process. The structure of this thesis is determined by the techniques and materials of the daguerreotype in the order of practice related to improvements in speed, tone and spectral sensitivity, which were the prime motivation for advancements. Chapters are devoted to the silver plate, iodine sensitizing, halogen acceleration, and optics and their contribution toward image quality is revealed. The evolution of the lens is explained using some of the oldest cameras extant. Daguerre’s discovery of the latent image is presented as the result of tacit experience rather than fortunate accident. -

What's on Guide Ad 210Mm X 148Mm.Indd 1 07/01/2015 11:43 Defi Ning Beauty the Body in Ancient Greek Art

What’s On March – May 2015 npg.org.uk Welcome About the Gallery The National Portrait Gallery is home to the largest Make the most of your visit with an Audio Visual collection of portraits in the world and celebrates the Guide (£3) available from the Information Desk, lives and achievements of those who have influenced featuring interactive maps, exclusive interviews and British history, culture and identity. themed tours. Family Audio Visual Guides are available, charges apply. npg.org.uk View over 115,000 works in the Collection and find The Visitor Guide (£5), available from the Gallery out more about the Gallery. Shops and Information Desk, highlights key portraits and fascinating stories. Explore the Collection and create your own tours using the interactive touch-screens in the The Gallery App (£1.19) is a perfect addition to your Digital Space. visit with video introductions, Collection highlights and floorplans. Available from iTunes. Keep in touch Register online for the Gallery’s free enewsletter. Pick up a Map to help plan your visit, including /nationalportraitgallery @npglondon suggested highlights, and support the Gallery with @nationalportraitgallery a £1 donation. Late Shift Take a break from the routine and explore the Gallery at Late Shift every Thursday and Friday until 21.00. Be inspired by our programme of regular events including drop-in drawing, live music and talks or relax with a drink at the Late Shift Bar. npg.org.uk/lateshift Exhibitions Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends 12 February – 25 May 2015 Wolfson Gallery John Singer Sargent (1856 – 1925) was the greatest portrait painter of his generation. -

Photography As Exhibited in the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, 1851

PHOTOGRAPHY AS EXHIBITED IN THE GREAT EXHIBITION OF THE WORKS OF INDUSTRY OF ALL NATIONS, 1851 by Robin O’Dell Associate of Science, Montreat College, 1981 Bachelor of Arts, University Of South Florida, 1986 A thesis presented to Ryerson University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in the program of Photographic Preservation and Collections Management Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2013 ©Robin O’Dell 2013 AUTHOR'S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A THESIS I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this thesis to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this thesis by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii PHOTOGRAPHY AS EXHIBITED IN THE GREAT EXHIBITION OF THE WORKS OF INDUSTRY OF ALL NATIONS, 1851 Master of Arts, 2013 Robin O’Dell Photographic Preservation and Collections Management Ryerson University and George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film ABSTRACT The 1851 Great Exhibition of the Works of All Nations was the first world’s fair and the first time that photographs from around the world were exhibited together. To accompany the exhibition, the Royal Commissioners created a set of volumes that included an Official Catalogue and Reports by the Juries. -

The North King Country

North King Country Orientation Package Welcome to the North King Country We hope that your time here is happy and rewarding. We ask that you evaluate this orientation package and provide us with comments so we can update the contents on a regular basis. In this way it will retain its value for future health workers in this area. Profile of the North King Country Geography Known by M!ori as Te Rohe Potae, "The Area of the Hat", the King Country region extends along the west coast of New Zealand's North Island from Mt. Pirongia in the north to the coastal town of M"kau in the south. It stretches inland to Pureora Forest Park and the Waikato River. The North King Country is comprised of two local authorities, the Otorohanga District and The Waitomo District. The area covers a landmass totalling 5,610 km2 (Otorohanga – 2,063 km2 or 37% of the total and Waitomo – 3,547 km2 or 63% of the total). The total population of the North King Country is 18,516 people, including 9,075 (49%) in Otorohanga District and 9,441 (51%) in Waitomo District1. Otorohanga District has one large centre, Otorohanga (population 3,547), and one smaller centre, K!whia (390). Waitomo District has one large centre, Te Kuiti (4,419) and a number of smaller centres – Piopio (468), Tah!roa (216), Bennydale, Awakino, M"kau, and Waitomo Caves. The area is mainly rural with population density that is below the national average. Population density in Waitomo District is 2.7 per km2 compared with 4.4 per km2 in Otorohanga District and 14.9 per km2 Figure 2 - M!kau Vista 1 All demographic statistics are based on the 2006 Census, May 2009 Page 7 North King Country Orientation Package nationally.