Whanganui Ki Maniapoto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Native Land Court, Land Titles and Crown Land Purchasing in the Rohe Potae District, 1866 ‐ 1907

Wai 898 #A79 The Native Land Court, land titles and Crown land purchasing in the Rohe Potae district, 1866 ‐ 1907 A report for the Te Rohe Potae district inquiry (Wai 898) Paul Husbands James Stuart Mitchell November 2011 ii Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Report summary .................................................................................................................................. 1 The Statements of Claim ..................................................................................................................... 3 The report and the Te Rohe Potae district inquiry .............................................................................. 5 The research questions ........................................................................................................................ 6 Relationship to other reports in the casebook ..................................................................................... 8 The Native Land Court and previous Tribunal inquiries .................................................................. 10 Sources .............................................................................................................................................. 10 The report’s chapters ......................................................................................................................... 20 Terminology ..................................................................................................................................... -

Community Services

North King Country Orientation Package Community Services Accommodation Real Estate Provide advice on rental and purchasing of real estate. Bruce Spurdle First National Real Estate. 18 Hinerangi St, Te Kuiti. 027 285 7306 Century 21 Countrywide Real Estate. 131 Rora St, Te Kuiti. 07 878 8266 Century 21 Countrywide Real Estate. 45 Maniapoto St, Otorohanga. 07 873 6083 Gold 'n' Kiwi Realty. 07 8737494 Harcourts. 130 Maniapoto St, Otorohanga 07 873 8700 Harcourts. 69 Rora St, Te Kuiti. 07 878 8700 Waipa Property Link. K!whia 07 871 0057 Information about property sales and rental prices Realestate.co.nz, the official website of the New Zealand real estate industry http://www.realestate.co.nz/ Terralink International Limited http://www.terranet.co.nz/ Quotable Value Limited (QV) http://www.qv.co.nz/ Commercial Accommodation Providers Abseil Inn Bed & Breakfast. Waitomo Caves Rd. Waitomo Caves 07 878 7815 Angus House Homestay/ B & B. 63 Mountain View Rd. Otorohanga 07 873 8955 Awakino Hotel. Main Rd. M"kau 06 752 9815 Benneydale Hotel. Ellis Rd. Benneydale 07 878 4708 Blue Chook Inn. Jervois St. K!whia 07 871 0778 Carmel Farm Stay. Main Rd. Piopio 07 877 8130 Casara Mesa Backpackers. Mangarino Rd. Te Kuiti 07 878 6697 Caves Motor Inn. 728 State Highway 3. Hangatiki Junction. Waitomo 07 873 8109 Churstain Bed & Breakfast. 129 Gadsby Rd. Te Kuiti 07 878 8191 Farm Bach Mahoenui. RD, Mahoenui 07 877 8406 Glow Worm Motel. Corner Waitomo Caves Rd. Hangatiki 07 873 8882 May 2009 Page 51 North King Country Orientation Package Juno Hall Backpackers. -

New Zealand Wars Sources at the Hocken Collections Part 2 – 1860S and 1870S

Reference Guide New Zealand Wars Sources at the Hocken Collections Part 2 – 1860s and 1870s Henry Jame Warre. Camp at Poutoko (1863). Watercolour on paper: 254 x 353mm. Accession no.: 8,610. Hocken Collections/Te Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago Library Nau Mai Haere Mai ki Te Uare Taoka o Hākena: Welcome to the Hocken Collections He mihi nui tēnei ki a koutou kā uri o kā hau e whā arā, kā mātāwaka o te motu, o te ao whānui hoki. Nau mai, haere mai ki te taumata. As you arrive We seek to preserve all the taoka we hold for future generations. So that all taoka are properly protected, we ask that you: place your bags (including computer bags and sleeves) in the lockers provided leave all food and drink including water bottles in the lockers (we have a researcher lounge off the foyer which everyone is welcome to use) bring any materials you need for research and some ID in with you sign the Readers’ Register each day enquire at the reference desk first if you wish to take digital photographs Beginning your research This guide gives examples of the types of material relating to the New Zealand Wars in the 1860s and 1870s held at the Hocken. All items must be used within the library. As the collection is large and constantly growing not every item is listed here, but you can search for other material on our Online Public Access Catalogues: for books, theses, journals, magazines, newspapers, maps, and audiovisual material, use Library Search|Ketu. -

Treaties Nobody Counted On

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Open Journal Systems at the Victoria University of Wellington Library 653 TREATIES NOBODY COUNTED ON R P Boast* This article is based on the author's inaugural professorial lecture delivered at Victoria University of Wellington in March 2011. The author's subject is treaties and treaty-like agreements, entered into between the New Zealand government and Māori after the Treaty of Waitangi. In the early 1880s there was a prolonged process of negotiation between representatives of an indigenous and autonomous Polynesian state; a state which a prominent New Zealand historian has described as being "two thirds the size of Belgium" which "not all historians have noticed".1 This autonomous state had its own monarch, a port of its own, and was actively trying to build its economy, manage its own lands, and develop overseas trade and commerce. The process of negotiation took a number of years, involved frequent consultations at the highest level, was embodied in a number of documents, and was given effect to in legislation. To this day, those negotiations and the agreements that came out of them remain pivotal to the indigenous groups affected and are well-remembered. I am speaking of the King Country, and the negotiations that took place in the 1880s in which two Native Ministers, John Bryce and John Ballance, were involved, as well as King Tawhiao and a number of leading rangatira of the Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Raukawa and other tribes.2 The historian I have referred to is of course Professor James Belich, who at the end of his The New Zealand Wars, expressed his puzzlement that the persistence of this independent Māori state in the middle of the North Island could remain off the historical radar for so long. -

Documenting Maori History

Documenting Maori History: THE ARREST OF TE KOOTI RIKIRANGI TE TURUKI, 1889* TRUTH is ever a casualty of war and of the aftermath of war and so it is of the conflicts between Maori and Pakeha in New Zealand. A bare hun- dred years is too short a time for both peoples, still somewhat uncertainly working out their relationships in New Zealand, to view the nineteenth- century conflicts with much objectivity. Indeed, partly due to the con- fidence and articulateness of the younger generations of Maoris and to their dissatisfaction with the Pakeha descriptions of what is and what happened, the covers have only in the last decade or so really begun to be ripped off the struggles of a century before. Some truth is emerging, in the sense of reasonably accurate statements about who did what and why, but so inevitably is a great deal of myth-making, of the casting of villains and the erection of culture-heroes by Maoris to match the villains and culture-heroes which were created earlier by the Pakeha—and which many Pakeha of a post-imperial generation now themselves find very inadequate. In all of this academics are going to become involved, partly because they are going to be dragged into it by the public, by their students and by the media, and partly because it is going to be difficult for some of them to resist the heady attractions of playing to the gallery of one set or another of protagonists or polemicists, frequently eager to have the presumed authority of an academic imprimatur on their particular ver- sion of what is supposed to have happened. -

Negative Kept

[ THIS PAGE ] Batt and Richards (fl . 1867-1874). Maori Fisherman. Verso with inscribed title and photographers’ imprint. Albumen print, actual size. [ ENDPAPERS ] Thomas Price (fl . c. 1867-1920s). Collage of portraits, rephotographed in a carved wood frame, c. 1890. Gelatin silver print, 214 by 276 mm. [ COVER ] Portrait, c. 1870. Albumen print, actual size. Negative kept Negative In memoryofRogerNeichandJudithBinney Maori andthe John Leech Gallery, Auckland,2011 John LeechGallery, Introductory essayIntroductory byKeith Giles Michael Graham-Stewart in association with in association John Gow carte devisite _ 004 Preface Photography was invented, or at least entered the public sphere, in France and England in 1839 with the near simultaneous announcements of the daguerreotype and photogenic drawing techniques. The new medium was to have as great an infl uence on humankind and the transmission of history as had the written and printed word. Visual, as well as verbal memory could now be fi xed and controlled; our relationship with time forever altered. However, unlike text, photography experienced a rapid mutation through a series of formats in the 19th century culminating in fi lm, a sequence of stopped motion images. But even as this latest incarnation spread, earlier forms persisted: stereographs, cabinet cards and what concerns us here, the carte de visite. Available from the late 1850s, this small and tactile format rapidly expanded the reach of photography away from just the wealthy. In the words of the Sydney Morning Herald of 5 May 1859: Truly this is producing portraits for the million (the entire population of white Australia). Seeing and handling a carte would have been most New Zealanders’ fi rst photographic experience. -

Te Wairua Kōmingomingo O Te Māori = the Spiritual Whirlwind of the Māori

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. TE WAIRUA KŌMINGOMINGO O TE MĀORI THE SPIRITUAL WHIRLWIND OF THE MĀORI A thesis presented for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Māori Studies Massey University Palmerston North, New Zealand Te Waaka Melbourne 2011 Abstract This thesis examines Māori spirituality reflected in the customary words Te Wairua Kōmingomingo o te Maori. Within these words Te Wairua Kōmingomingo o te Māori; the past and present creates the dialogue sources of Māori understandings of its spirituality formed as it were to the intellect of Māori land, language, and the universe. This is especially exemplified within the confinements of the marae, a place to create new ongoing spiritual synergies and evolving dialogues for Māori. The marae is the basis for meaningful cultural epistemological tikanga Māori customs and traditions which is revered. Marae throughout Aotearoa is of course the preservation of the cultural and intellectual rights of what Māori hold as mana (prestige), tapu (sacred), ihi (essence) and wehi (respect) – their tino rangatiratanga (sovereignty). This thesis therefore argues that while Christianity has taken a strong hold on Māori spirituality in the circumstances we find ourselves, never-the-less, the customary, and traditional sources of the marae continue to breath life into Māori. This thesis also points to the arrival of the Church Missionary Society which impacted greatly on Māori society and accelerated the advancement of colonisation. -

Download Download

VOLUME 125 No.4 DECEMBER 2016 VOLUME THE JOURNAL OF THE POLYNESIAN SOCIETY VOLUME 125 No.4 DECEMBER 2016 THE JOURNAL OF THE POLYNESIAN SOCIETY Volume 125 DECEMBER 2016 Number 4 Editor MELINDA S. ALLEN Review Editors LYN CARTER ETHAN COCHRANE Editorial Assistant DOROTHY BROWN Published quarterly by the Polynesian Society (Inc.), Auckland, New Zealand Cover image: The carved waharoa ‘gateway’ that stands as a tohu maumahara ‘symbol of remembrance’ at Rangiriri Pā, Waikato. It was erected in November 2012 to commemorate the 149th anniversary of the Battle of Rangiriri. Photograph supplied by Vincent O’Malley. Published in New Zealand by the Polynesian Society (Inc.) Copyright © 2016 by the Polynesian Society (Inc.) Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this publication may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be made to: Hon. Secretary [email protected]. The Polynesian Society c/- Mäori Studies University of Auckland Private Bag 92019, Auckland ISSN 0032-4000 (print) ISSN 2230-5955 (online) Indexed in SCOPUS, WEB OF SCIENCE, INFORMIT NEW ZEALAND COLLECTION, INDEX NEW ZEALAND, ANTHROPOLOGY PLUS, ACADEMIC SEARCH PREMIER, HISTORICAL ABSTRACTS, EBSCOhost, MLA INTERNATIONAL BIBLIOGRAPHY, JSTOR, CURRENT CONTENTS (Social & Behavioural Sciences). AUCKLAND, NEW ZEALAND Volume 125 DECEMBER 2016 Number 4 CONTENTS Notes and News ..................................................................................... 337 David Simmons, MBE (1930–2015) Obituary by Richard A. Benton ............................................................ 339 Articles VINCENT O’MALLEY A Tale of Two Rangatira: Rewi Maniapoto, Wiremu Tamihana and the Waikato War ............................................................................. 341 MERATA KAWHARU Indigenous Entrepreneurship: Cultural Coding and the Transformation of Ngāti Whātua in New Zealand ...................... -

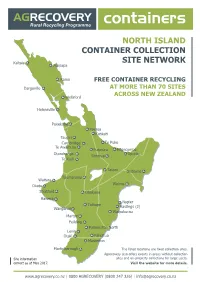

North Island Container Collection Site Network

NORTH ISLAND CONTAINER COLLECTION Kaitaia SITE NETWORK Waipapa Kamo FREE CONTAINER RECYCLING Dargaville AT MORE THAN 70 SITES ACROSS NEW ZEALAND Wellsford Helensville Pukekohe Paeroa Katikati Taupiri Cambridge Te Puke Te Awamutu Putaruru Edgecumbe Otorohanga Opotiki Rotorua Te Kuiti Taupo Gisborne Taumarunui Waitara Wairoa Okato Stratford Ohakune Hawera Napier Taihape Hastings (2) Wanganui Waipukurau Marton Feilding Palmerston North Levin Otaki Pahiatua Masterton Martinborough The listed locations are fixed collection sites. Agrecovery also offers events in areas without collection Site information sites and on-property collections for large users. correct as at May 2017. Visit the website for more details. www.agrecovery.co.nz | 0800 AGRECOVERY (0800 247 326) | [email protected] North Island Collection Sites Address Opening Hours NORTHLAND Dargaville Farmlands 1 River Road Monday to Friday 8:30am - 4pm Kaitaia Farmlands 31 North Park Drive Monday to Friday 8:30am - 4pm Kamo Farmlands 2 Springs Flat Road Monday to Friday 8am - 5pm Waipapa PGG Wrightson Cnr State Highway 10 & Pataka Lane Monday to Friday 8am - 5pm AUCKLAND Helensville Helensville Community 31 Mill Road Thursday to Sunday 8am - 4pm Recycling Centre Pukekohe Farmlands 86A Harris Street Monday to Friday 8am - 5pm Wellsford Farmlands 113 Centennial Park Road Monday to Friday 8am - 5pm Waiheke Island Contact Steve Sherson of Fruitfed Supplies on 027 479 7338 WAIKATO Cambridge Farmlands Hautapu 64 Hautapu Road Monday to Friday 8am - 5pm Otorohanga VETFOCUS 9 Wahanui Crescent -

Māori Representation in a Shrunken Parliament

New Zealand Journal of History, 52, 2 (2018) Māori Representation in a Shrunken Parliament IN A REFERENDUM held in conjunction with New Zealand’s 2011 general election, Māori overwhelmingly supported the retention of the Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) voting system introduced in 1996. Māori support for MMP was significantly less equivocal than that of the general population.1 The extent of support is understandable. MMP brought many benefits for Māori voters, most obviously a large increase in Māori representation in Parliament.2 The bulk of Māori votes were no longer tied up in just four electorates where they could often be safely ignored. With all votes being equal, political parties had a heightened motivation to pay heed to Māori aspirations and to put forward Māori candidates. The benefits of MMP for Māori were increased through the retention of seats reserved for voters of Māori descent, along with the innovation of linking the number of such seats directly with the numbers enrolled to vote in them. In 1996 the number of Māori seats increased to five under the new rules, and further increased to seven in 2002.3 Previously the number of reserved Māori seats was fixed at four, and had been since 1867.4 New Zealand adopted MMP following a binding referendum held in 1993. In 1990 Ranginui Walker summarized some of the faults with the electoral system then in place, pointing to both historical and ongoing discrimination. Whereas the secret ballot applied in European electorates from 1870, it did not apply in Māori electorates until 1937.5 There were no Māori electoral rolls until 1949 and compulsory voter registration was not introduced for Māori until 1956. -

Aspects of Rohe Potae Political Engagement, 1886 to 1913

OFFICIAL Wai 898 #A71 Aspects of Rohe Potae Political Engagement, 1886 to 1913 Dr Helen Robinson and Dr Paul Christoffel A report commissioned by the Waitangi Tribunal for the Te Rohe Potae (Wai 898) district inquiry August 2011 RECEIVED Waitangi Tribunal 31 Aug 2011 Ministry of Justice WELLINGTON Authors Dr Paul John Christoffel has been a Research Analyst/Inquiry Facilitator at the Waitangi Tribunal Unit since December 2006. He has a PhD in New Zealand history from Victoria University of Wellington and 18 years experience in policy and research in various government departments. His previous report for the Tribunal was entitled ‘The Provision of Education Services to Maori in Te Rohe Potae, 1840 – 2010’ (Wai 898, document A27). Dr Helen Robinson has been a Research Analyst/Inquiry Facilitator at the Waitangi Tribunal Unit since April 2009 and has a PhD in history from the University of Auckland. She has published articles in academic journals in New Zealand and overseas, the most recent being ‘Simple Nullity or Birth of Law and Order? The Treaty of Waitangi in Legal and Historiographical Discourse from 1877 to 1970’ in the December 2010 issue of the New Zealand Universities Law Review. Her previous report for the Tribunal was ‘Te Taha Tinana: Maori Health and the Crown in Te Rohe Potae Inquiry District, 1840 to 1990’ (Wai 898, document A31). i Contents Authors i Contents ii List of maps v List of graphs v List of figures v Introduction 1 The approach taken 2 Chapter structure 3 Claims and sources 4 A note on geographical terminology -

CHAPTER TWO Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki

Te Kooti’s slow-cooking earth oven prophecy: A Patuheuheu account and a new transformative leadership theory Byron Rangiwai PhD ii Dedication This book is dedicated to my late maternal grandparents Rēpora Marion Brown and Edward Tapuirikawa Brown Arohanui tino nui iii Table of contents DEDICATION ..................................................................................................................... iii CHAPTER ONE: Introduction ............................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER TWO: Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki .......................................................... 18 CHAPTER THREE: The Significance of Land and Land Loss ..................................... 53 CHAPTER FOUR: The emergence of Te Umutaoroa and a new transformative leadership theory ................................................................................................. 74 CHAPTER FIVE: Conclusion: Reflections on the Book ................................................. 83 BIBLIOGRAPHY ................................................................................................................ 86 Abbreviations AJHR: Appendices to the Journals of the House of Representatives MS: Manuscript MSS: Manuscripts iv CHAPTER ONE Introduction Ko Hikurangi te maunga Hikurangi is the mountain Ko Rangitaiki te awa Rangitaiki is the river Ko Koura te tangata Koura is the ancestor Ko Te Patuheuheu te hapū Te Patuheuheu is the clan Personal introduction The French philosopher Michel Foucault stated: “I don't