Art at Vassar, Spring/Summer 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Use This Guide

How to Use this Guide The New-York Historical Society, one of America’s pre-eminent cultural institutions, is dedicated to fostering research, presenting history and art exhibitions, and public programs that reveal the dynamism of history and its influence on the world of today. Founded in 1804, New-York Historical has a mission to explore the richly layered political, cultural and social history of New York City and State and the nation, and to serve as a national forum for the discussion of issues surrounding the making and meaning of history. Student Historians are high school interns at New-York Historical who explore our museum and library collection and conduct research using the resources available to them within a museum setting. Their project this academic year was to create a guide for fellow high school students preparing for U.S. History Exams, particularly the U.S. History & Government Regents Exam. Each Student Historian chose a piece from our collection that represents a historical event or theme often tested on the exam, collected and organized their research, and wrote about their piece within its historic context. The intent is that this catalog will provide a valuable supplemental review material for high school students preparing for U.S. History Exams. The following summative essays are all researched and written by the 2015-16 Student Historians, compiled in chronological order, and organized by unit. Each essay includes an image of the object or artwork from the N-YHS collection that serves as the foundation for the U.S. History content reviewed. Additional educational supplementary materials include a glossary of frequently used terms, review activities including a crossword puzzle as well as questions and answers taken from past U.S. -

Finding Aid for the John Sloan Manuscript Collection

John Sloan Manuscript Collection A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum The John Sloan Manuscript Collection is made possible in part through funding of the Henry Luce Foundation, Inc., 1998 Acquisition Information Gift of Helen Farr Sloan, 1978 Extent 238 linear feet Access Restrictions Unrestricted Processed Sarena Deglin and Eileen Myer Sklar, 2002 Contact Information Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives Delaware Art Museum 2301 Kentmere Parkway Wilmington, DE 19806 (302) 571-9590 [email protected] Preferred Citation John Sloan Manuscript Collection, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum Related Materials Letters from John Sloan to Will and Selma Shuster, undated and 1921-1947 1 Table of Contents Chronology of John Sloan Scope and Contents Note Organization of the Collection Description of the Collection Chronology of John Sloan 1871 Born in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania on August 2nd to James Dixon and Henrietta Ireland Sloan. 1876 Family moved to Germantown, later to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. 1884 Attended Philadelphia's Central High School where he was classmates with William Glackens and Albert C. Barnes. 1887 April: Left high school to work at Porter and Coates, dealer in books and fine prints. 1888 Taught himself to etch with The Etcher's Handbook by Philip Gilbert Hamerton. 1890 Began work for A. Edward Newton designing novelties, calendars, etc. Joined night freehand drawing class at the Spring Garden Institute. First painting, Self Portrait. 1891 Left Newton and began work as a free-lance artist doing novelties, advertisements, lettering certificates and diplomas. 1892 Began work in the art department of the Philadelphia Inquirer. -

Hamilton Easter Fiel

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Paintings by John W. Alexander ; Sculpture by Chester Beach

SPECIAL EXHIBITIONS THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO, DECEMBER 12 1916 TO JANUARY 2, 1917 PAINTINGS BY JOHN W. ALEXANDER SCULPTURE BY CHESTER BEACH PAINTINGS BY CALIFORNIA ARTISTS PAINTINGS BY WILSON IRVINE PAINTINGS BY EDWARD W. REDFIELD PAINTINGS, DRAWINGS AND SKETCHES BY MAURICE STERNE 0 SPECIAL EXHIBITIONS OF WORK BY THE FOLLOWING ARTISTS PAINTINGS BY JOHN W. ALEXANDER SCULPTURE BY CHESTER BEACH PAINTINGS BY CALIFORNIA ARTISTS PAINTINGS BY WILSON IRVINE PAINTINGS BY EDWARD W. REDFIELD PAINTINGS, DRAWINGS AND SKETCHES BY MAURICE STERNE THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO DEC. 12, 1916 TO JAN. 2, 1917 PAINTINGS BY JOHN WHITE ALEXANDER OHN vV. ALEXANDER. Born, Pittsburgh, J Pennsylvania, 1856. Died, New York, May 31, 1915. Studied at the Royal Academy, Munich, and with Frank Duveneck. Societaire of Societe Nationale des Beaux Arts, Paris; Member of the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers, London; Societe Nouvelle, Paris ; Societaire of the Royal Society of Fine Arts, Brussels; President of the National Academy of Design, New York; President of the Natiomrl Academy Association; President of the National Society of Mural Painters, New York; Ex- President of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, New York; American Academy of Arts and Letters; Vice-President of the National Fine Arts Federation, Washington, D. C.; Member of the Architectural League, Fine Arts Federation and Fine Arts Society, New York; Honorary Member of the Secession Society, Munich, and of the Secession Society, Vienna; Hon- orary Member of the Royal Society of British Artists, of the American Institute of Architects and of the New York Society of Illustrators; President of the School Art League, New York; Trustee of the New York Public Library; Ex-President of the MacDowell Club, New York; Trustee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Trustee of the American Academy in Rome; Chevalier of the Legion of Honor, France; Honorary Degree of Master of Arts, Princeton University, 1892, and of Doctor of Literature, Princeton, 1909. -

Appendix A. Natioan Commission on Forensic Science Commissioners

Reflecting Back—Looking Toward the Future: Appendix A Appendix A. National Commission on Forensic Science Commissioners and Biographies Co-Chairs: Arturo Casadevall, Ph.D. Marc LeBeau, Ph.D. Acting Deputy Attorney General Gregory Champagne Julia Leighton Dana J. Boente Cecelia Crouse, Ph.D. Hon. Bridget Mary McCormack Acting NIST Director and Under Gregory Czarnopys Peter Neufeld Secretary of Commerce for Standards & Technology Kent Deirdre Daly Phil Pulaski Rochford, Ph.D. M. Bonner Denton, Ph.D. Matthew Redle Vice-Chairs: Jules Epstein Sunita Sah, Ph.D. Nelson Santos John Fudenberg Michael “Jeff” Salyards, Ph.D. John Butler, Ph.D. S. James Gates, Jr., Ph.D. Ex-Officio Members: Commission Staff: Dean Gialamas Rebecca Ferrell, Ph.D. Jonathan McGrath, Ph.D. (DFO) Paul Giannelli David Honey, Ph.D. Danielle Weiss Randy Hanzlick, M.D. Marilyn Huestis, Ph.D. Lindsay DePalma Hon. Barbara Hervey Gerald LaPorte Susan Howley Commission Members: Patricia Manzolillo Ted Hunt Thomas Albright, Ph.D. Hon. Jed Rakoff Linda Jackson Suzanne Bell, Ph.D. Frances Schrotter Hon. Pam King Frederick Bieber, Ph.D. Kathryn Turman Troy Lawrence Former Chairs: Former Commission Members: James M. Cole Thomas Cech, Ph.D. Patrick Gallagher, Ph.D. William Crane Willie E. May, Ph.D. Vincent DiMaio, M.D. Sally Q. Yates Troy Duster, Ph.D. Andrea Ferreira-Gonzalez, Ph.D. Former Commission Staff: Andrew J. Bruck Stephen Fienberg, Ph.D. Robin Jones John Kacavas Brette Steele Ryant Washington Victor Weedn, M.D. Former Ex-Officio Members: Mark Weiss, Ph.D. 1 Reflecting Back—Looking Toward the Future: Appendix A NCFS Co-Chairs Dana J. -

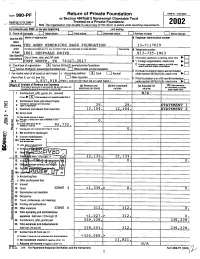

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

OMB No 1545-OX2 Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust n Treated as a Private Foundation 200 Node The organization may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements 2 For calendar year 2002, or tai year beginning , and ending G Check all that a E:1 initial return 0 Final return LA Amended return 0 Address than e 0 Name clan e Use the IRS Name of organization A Employer Identification number label Otherwise, HE ANNE HENDRICKS BASS FOUNDATION 13-7117629 print Number enUstreet (orPO Dwnumb>Il noel isnot aarvensnmstreet aearess) amw"uim B Telephone number orqpe 1801 DEEPDALE DRIVE 817-735-1863 See Specific town, ZIP Instructions City or state, and code C u am,Pem~~vl~~t~~ t" amaina ~~ nM " 0 FORT WORTH TX 76107-3517 D 1 Foreign orpaniutions,check here mi-0 2 ~~IWn ~l~x~oo^unpNe65%tcS ~ H Check type of organization XSection501(c)(3)exemptprrvatefoundatian mpubeon Section 4947(a)(1) nonerempl charrta0le trust = Other taxable private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method OX Cash Ej Accrual under section 507(b)(t)(A), check here (/turn Part ll, cot (c), line 16) 0 Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination 10.$ 3 8 3 7 918 . (Pert I, column (d) must be on cash basis) under section 507 b 1 B check here 0- EJ I Analysis of Revenue and Expenses (a) Revenue and (h) Net (0) oiswrs~d (fTe mm of ertnunb In mlumnf (b) (b. -

Old Spanish Masters Engraved by Timothy Cole

in o00 eg >^ ^V.^/ y LIBRARY OF THE University of California. Class OLD SPANISH MASTERS • • • • • , •,? • • TIIK COXCEPTION OF THE VIRGIN. I!V MURILLO. PRADO Mi;SEUAI, MADKIU. cu Copyright, 1901, 1902, 1903, 1904, 1905, 1906, and 1907, by THE CENTURY CO. Published October, k^j THE DE VINNE PRESS CONTENTS rjuw A Note on Spanish Painting 3 CHAPTER I Early Native Art and Foreign Influence the period of ferdinand and isabella (1492-15 16) ... 23 I School of Castile 24 II School of Andalusia 28 III School of Valencia 29 CHAPTER II Beginnings of Italian Influence the PERIOD OF CHARLES I (1516-1556) 33 I School of Castile 37 II School of Andalusia 39 III School of Valencia 41 CHAPTER III The Development of Italian Influence I Period of Philip II (l 556-1 598) 45 II Luis Morales 47 III Other Painters of the School of Castile 53 IV Painters of the School of Andalusia 57 V School of Valencia 59 CHAPTER IV Conclusion of Italian Influence I of III 1 Period Philip (1598-162 ) 63 II El Greco (Domenico Theotocopuli) 66 225832 VI CONTENTS CHAPTER V PACE Culmination of Native Art in the Seventeenth Century period of philip iv (162 1-1665) 77 I Lesser Painters of the School of Castile 79 II Velasquez 81 CHAPTER VI The Seventeenth-Century School of Valencia I Introduction 107 II Ribera (Lo Spagnoletto) log CHAPTER VII The Seventeenth-Century School of Andalusia I Introduction 117 II Francisco de Zurbaran 120 HI Alonso Cano x. 125 CHAPTER VIII The Great Period of the Seventeenth-Century School of Andalusia (continued) 133 CHAPTER IX Decline of Native Painting ii 1 charles ( 665-1 700) 155 CHAPTER X The Bourbon Dynasty FRANCISCO GOYA l6l INDEX OF ILLUSTRATIONS MuRiLLO, The Conception of the Virgin . -

Connoisseurs Comes Into Renewed Durkheim, Weber, and Garfinkel, Chapel Hill, North Focus

FOCUSINON Fahlman aptly compares the tone of Pène du Bois’ paintings SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING and commentary—“ironically humorous rather than bitingly sarcastic”—to the tone of The New Yorker magazine. That The Cortissoz, Royal, Guy Pène du Bois, New York, 1931. New Yorker caters to the economic elite can be discerned just from perusing the gift suggestions and ads for $20,000 bracelets. Fahlman, Betsy, Guy Pène du Bois, Artist About Town, exhibition It also caters to the well-educated, as indexed by literary catalogue, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1980. references, and even cartoons that are occasionally impossible to Fahlman, Betsy, Guy Pène du Bois, Painter of Modern Life, New decipher without insider knowledge. Yet the magazine is directed York, 2004. to general audiences and seems to make well-targeted fun of the Fahlman, Betsy, “Imaging the Twenties: The Work of Guy Pène very culture in which it travels. It is a well-intentioned, self- du Bois,” Guy Pène du Bois: The Twenties at Home and denigrating fun, and it is the kind of fun general audiences like to Abroad, exhibition catalogue, Sordoni Gallery, Wilkes see being made of the cultural elite. Tending to the left of the University, Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, 1995. political spectrum it is a “people’s magazine,” but it is also an Garfinkel, Harold, Studies in Ethnomethodology, Cambridge, artifact of privilege to which most of its readership could not England, 1984. possibly aspire. Occasionally it publishes articles explaining previously indecipherable cartoons, but it does so in a high Goffman, Erving, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, cultured way that does not appear to denigrate any reader’s London, 1969. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Secondary Fiber Recycling 01993 TAPPI PRESS Atlanta. Georgia iii Preface v List of Contributors vii Table of Contents ix List of Figures and Tables Chapter 1 Recovered Paper and the U.S. Solid Waste Dilemma I 1 by Rodney Young Introduction and Overview ............................................ 1 Paper Industry Response to the Solid Waste Issue ................................ 2 U.S. Recovered Paper Consumption ..................................... 2 U.S. Trade in Recovered Paper ........................................ 3 U.S. Recovered Paper Recovery ....................................... 3 Recovered Paper Supply and Cost ...................................... 3 Bibliography .................................................... 4 Resources ................................................... 4 Chapter 2 Recycled- Versus Virgin-Fiber Characteristics: A Comparison 1 7 by R. L. Ellls and K. M. Ssdlachsk Introduction ..................................................... 7 Literature Review ................................................. 8 General Effect of Recycling ......................................... 8 Effect of Furnish .............................................. 10 Effect of initial Beating of Virgin Pulp ................................... 10 Theory for Tensile Strength of Paper .................................... 10 First Assumption ............................................ 11 Second Assumption .......................................... 12 Theory Verification ............................................ -

Negative Kept

[ THIS PAGE ] Batt and Richards (fl . 1867-1874). Maori Fisherman. Verso with inscribed title and photographers’ imprint. Albumen print, actual size. [ ENDPAPERS ] Thomas Price (fl . c. 1867-1920s). Collage of portraits, rephotographed in a carved wood frame, c. 1890. Gelatin silver print, 214 by 276 mm. [ COVER ] Portrait, c. 1870. Albumen print, actual size. Negative kept Negative In memoryofRogerNeichandJudithBinney Maori andthe John Leech Gallery, Auckland,2011 John LeechGallery, Introductory essayIntroductory byKeith Giles Michael Graham-Stewart in association with in association John Gow carte devisite _ 004 Preface Photography was invented, or at least entered the public sphere, in France and England in 1839 with the near simultaneous announcements of the daguerreotype and photogenic drawing techniques. The new medium was to have as great an infl uence on humankind and the transmission of history as had the written and printed word. Visual, as well as verbal memory could now be fi xed and controlled; our relationship with time forever altered. However, unlike text, photography experienced a rapid mutation through a series of formats in the 19th century culminating in fi lm, a sequence of stopped motion images. But even as this latest incarnation spread, earlier forms persisted: stereographs, cabinet cards and what concerns us here, the carte de visite. Available from the late 1850s, this small and tactile format rapidly expanded the reach of photography away from just the wealthy. In the words of the Sydney Morning Herald of 5 May 1859: Truly this is producing portraits for the million (the entire population of white Australia). Seeing and handling a carte would have been most New Zealanders’ fi rst photographic experience. -

British Art Studies November 2020 British Art Studies Issue 18, Published 30 November 2020

British Art Studies November 2020 British Art Studies Issue 18, published 30 November 2020 Cover image: Sonia E. Barrett, Table No. 6, 2013, wood and metal.. Digital image courtesy of Bruno Weiss. PDF generated on 21 July 2021 Note: British Art Studies is a digital publication and intended to be experienced online and referenced digitally. PDFs are provided for ease of reading offline. Please do not reference the PDF in academic citations: we recommend the use of DOIs (digital object identifiers) provided within the online article. Theseunique alphanumeric strings identify content and provide a persistent link to a location on the internet. A DOI is guaranteed never to change, so you can use it to link permanently to electronic documents with confidence. Published by: Paul Mellon Centre 16 Bedford Square London, WC1B 3JA https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk In partnership with: Yale Center for British Art 1080 Chapel Street New Haven, Connecticut https://britishart.yale.edu ISSN: 2058-5462 DOI: 10.17658/issn.2058-5462 URL: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk Editorial team: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/editorial-team Advisory board: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/advisory-board Produced in the United Kingdom. A joint publication by Contents Making a Case: Daguerreotypes, Steve Edwards Making a Case: Daguerreotypes Steve Edwards Abstract This essay considers physical daguerreotype cases from the 1840s and 1850s alongside scholarly debate on case studies, or “thinking in cases”, and some recent physicalist claims about objects in cultural theory, particularly those associated with “new materialism”. Throughout the essay, these three distinct strands are braided together to interrogate particular objects and broader questions of cultural history. -

ABSTRACT Title of Document: VISUALIZING AMERICAN

ABSTRACT Title of Document: VISUALIZING AMERICAN HISTORY AND IDENTITY IN THE ELLEN PHILLIPS SAMUEL MEMORIAL Abby Rebecca Eron, Master of Arts, 2014 Directed By: Professor Renée Ater, Department of Art History and Archaeology In her will, Philadelphia philanthropist Ellen Phillips Samuel designated $500,000 to the Fairmount Park Art Association “for the erection of statuary on the banks of the Schuylkill River … emblematic of the history of America from the time of the earliest settlers to the present.” The initial phase of the resulting sculpture project – the Central Terrace of the Samuel Memorial – should be considered one of the fullest realizations of New Deal sculpture. It in many ways corresponds (conceptually, thematically, and stylistically) with the simultaneously developing art programs of the federal government. Analyzing the Memorial project highlights some of the tensions underlying New Deal public art, such as the difficulties of visualizing American identity and history, as well as the complexities involved in the process of commissioning artwork intended to fulfill certain programmatic purposes while also allowing for a level of individual artists’ creative expression. VISUALIZING AMERICAN HISTORY AND IDENTITY IN THE ELLEN PHILLIPS SAMUEL MEMORIAL By Abby Rebecca Eron Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2014 Advisory Committee: Professor Renée Ater, Chair Professor Meredith J. Gill Professor Steven A. Mansbach © Copyright by Abby Rebecca Eron 2014 The thesis or dissertation document that follows has had referenced material removed in respect for the owner's copyright.