Air and Space Power Journal: Fall 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Living Under Drones Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians from US Drone Practices in Pakistan

Fall 08 September 2012 Living Under Drones Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians From US Drone Practices in Pakistan International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic Stanford Law School Global Justice Clinic http://livingunderdrones.org/ NYU School of Law Cover Photo: Roof of the home of Faheem Qureshi, a then 14-year old victim of a January 23, 2009 drone strike (the first during President Obama’s administration), in Zeraki, North Waziristan, Pakistan. Photo supplied by Faheem Qureshi to our research team. Suggested Citation: INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION CLINIC (STANFORD LAW SCHOOL) AND GLOBAL JUSTICE CLINIC (NYU SCHOOL OF LAW), LIVING UNDER DRONES: DEATH, INJURY, AND TRAUMA TO CIVILIANS FROM US DRONE PRACTICES IN PAKISTAN (September, 2012) TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I ABOUT THE AUTHORS III EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS V INTRODUCTION 1 METHODOLOGY 2 CHALLENGES 4 CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT 7 DRONES: AN OVERVIEW 8 DRONES AND TARGETED KILLING AS A RESPONSE TO 9/11 10 PRESIDENT OBAMA’S ESCALATION OF THE DRONE PROGRAM 12 “PERSONALITY STRIKES” AND SO-CALLED “SIGNATURE STRIKES” 12 WHO MAKES THE CALL? 13 PAKISTAN’S DIVIDED ROLE 15 CONFLICT, ARMED NON-STATE GROUPS, AND MILITARY FORCES IN NORTHWEST PAKISTAN 17 UNDERSTANDING THE TARGET: FATA IN CONTEXT 20 PASHTUN CULTURE AND SOCIAL NORMS 22 GOVERNANCE 23 ECONOMY AND HOUSEHOLDS 25 ACCESSING FATA 26 CHAPTER 2: NUMBERS 29 TERMINOLOGY 30 UNDERREPORTING OF CIVILIAN CASUALTIES BY US GOVERNMENT SOURCES 32 CONFLICTING MEDIA REPORTS 35 OTHER CONSIDERATIONS -

Congressional Record—Senate S4700

S4700 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE August 2, 2017 required. American workers have wait- of Kansas, to be a Member of the Na- billion each year in State and local ed too long for our country to crack tional Labor Relations Board for the taxes. down on abusive trade practices that term of five years expiring August 27, As I said at the beginning, I have had rob our country of millions of good- 2020. many differences with President paying jobs. The PRESIDING OFFICER. Under Trump, particularly on the issue of im- Today, I am proud to announce that the previous order, the time until 11 migration in some of the speeches and the Democratic Party will be laying a.m. will be equally divided between statements he has made, but I do ap- out our new policy on trade, which in- the two leaders or their designees. preciate—personally appreciate—that cludes, among other things, an inde- The assistant Democratic leader. this President has kept the DACA Pro- pendent trade prosecutor to combat DACA gram in place. trade cheating, not one of these endless Mr. DURBIN. Mr. President, many I have spoken directly to President WTO processes that China takes advan- times over the last 6 months, I have Trump only two times—three times, tage of over and over again; a new come to the Senate to speak out on perhaps. The first two times—one on American jobs security council that issues and to disagree with President Inauguration Day—I thanked him for will be able to review and stop foreign Trump. -

1945-12-11 GO-116 728 ROB Central Europe Campaign Award

GO 116 SWAR DEPARTMENT No. 116. WASHINGTON 25, D. C.,11 December- 1945 UNITS ENTITLED TO BATTLE CREDITS' CENTRAL EUROPE.-I. Announcement is made of: units awarded battle par- ticipation credit under the provisions of paragraph 21b(2), AR 260-10, 25 October 1944, in the.Central Europe campaign. a. Combat zone.-The.areas occupied by troops assigned to the European Theater of" Operations, United States Army, which lie. beyond a line 10 miles west of the Rhine River between Switzerland and the Waal River until 28 March '1945 (inclusive), and thereafter beyond ..the east bank of the Rhine.. b. Time imitation.--22TMarch:,to11-May 1945. 2. When'entering individual credit on officers' !qualiflcation cards. (WD AGO Forms 66-1 and 66-2),or In-the service record of enlisted personnel. :(WD AGO 9 :Form 24),.: this g!neial Orders may be ited as: authority forsuch. entries for personnel who were present for duty ".asa member of orattached' to a unit listed&at, some time-during the'limiting dates of the Central Europe campaign. CENTRAL EUROPE ....irst Airborne Army, Headquarters aMd 1st Photographic Technical Unit. Headquarters Company. 1st Prisoner of War Interrogation Team. First Airborne Army, Military Po1ie,e 1st Quartermaster Battalion, Headquar- Platoon. ters and Headquarters Detachment. 1st Air Division, 'Headquarters an 1 1st Replacementand Training Squad- Headquarters Squadron. ron. 1st Air Service Squadron. 1st Signal Battalion. 1st Armored Group, Headquarters and1 1st Signal Center Team. Headquarters 3attery. 1st Signal Radar Maintenance Unit. 19t Auxiliary Surgical Group, Genera]1 1st Special Service Company. Surgical Team 10. 1st Tank DestroyerBrigade, Headquar- 1st Combat Bombardment Wing, Head- ters and Headquarters Battery.: quarters and Headquarters Squadron. -

US Army Air Force 100Th-399Th Squadrons 1941-1945

US Army Air Force 100th-399th Squadrons 1941-1945 Note: Only overseas stations are listed. All US stations are summarized as continental US. 100th Bombardment Squadron: Organized on 8/27/17 as 106th Aero Squadron, redesignated 800th Aero Squadron on 2/1/18, demobilized by parts in 1919, reconstituted and consolidated in 1936 with the 135th Squadron and assigned to the National Guard. Redesignated as the 135th Observation Squadron on 1/25/23, 114th Observation Squadron on 5/1/23, 106th Observation Squadron on 1/16/24, federalized on 11/25/40, redesignated 106th Observation Squadron (Medium) on 1/13/42, 106th Observation Squadron on 7/4/42, 106th Reconnaissance Squadron on 4/2/43, 100th Bombardment Squadron on 5/9/44, inactivated 12/11/45. 1941-43 Continental US 11/15/43 Guadalcanal (operated through Russell Islands, Jan 44) 1/25/44 Sterling Island (operated from Hollandia, 6 Aug-14 Sep 44) 8/24/44 Sansapor, New Guinea (operated from Morotai 22 Feb-22 Mar 45) 3/15/45 Palawan 1941 O-47, O-49, A-20, P-39 1942 O-47, O-49, A-20, P-39, O-46, L-3, L-4 1943-5 B-25 100th Fighter Squadron: Constituted on 12/27/41 as the 100th Pursuit Squadron, activated 2/19/42, redesignated 100th Fighter Squadron on 5/15/42, inactivated 10/19/45. 1941-43 Montecorvino, Italy 2/21/44 Capodichino, Italy 6/6/44 Ramitelli Airfield, Italy 5/4/45 Cattolica, Italy 7/18/45 Lucera, Italy 1943 P-39, P-40 1944 P-39, P-40, P-47, P-51 1945 P-51 100th Troop Carrier Squadron: Constituted on 5/25/43 as 100th Troop transport Squadron, activated 8/1/43, inactivated 3/27/46. -

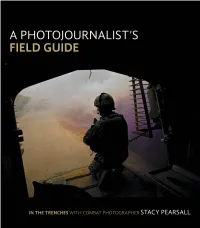

A Photojournalist's Field Guide: in the Trenches with Combat Photographer

A PHOTOJOURNALISt’S FIELD GUIDE IN THE TRENCHES WITH COMBAT PHOTOGRAPHER STACY PEARSALL A Photojournalist’s Field Guide: In the trenches with combat photographer Stacy Pearsall Stacy Pearsall Peachpit Press www.peachpit.com To report errors, please send a note to [email protected] Peachpit Press is a division of Pearson Education. Copyright © 2013 by Stacy Pearsall Project Editor: Valerie Witte Production Editor: Katerina Malone Copyeditor: Liz Welch Proofreader: Erin Heath Composition: WolfsonDesign Indexer: Valerie Haynes Perry Cover Photo: Stacy Pearsall Cover and Interior Design: Mimi Heft Notice of Rights All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or trans- mitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy- ing, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For information on getting permission for reprints and excerpts, contact [email protected]. Notice of Liability The information in this book is distributed on an “As Is” basis, without warranty. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of the book, neither the author nor Peachpit shall have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the instructions contained in this book or by the computer software and hardware products described in it. Trademarks Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and Peachpit was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations appear as requested by the owner of the trademark. -

70Th Annual 1St Cavalry Division Association Reunion

1st Cavalry Division Association 302 N. Main St. Non-Profit Organization Copperas Cove, Texas 76522-1703 US. Postage PAID West, TX Change Service Requested 76691 Permit No. 39 PublishedSABER By and For the Veterans of the Famous 1st Cavalry Division VOLUME 66 NUMBER 1 Website: http://www.1cda.org JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2017 The President’s Corner Horse Detachment by CPT Jeremy A. Woodard Scott B. Smith This will be my last Horse Detachment to Represent First Team in Inauguration Parade By Sgt. 833 State Highway11 President’s Corner. It is with Carolyn Hart, 1st Cav. Div. Public Affairs, Fort Hood, Texas. Laramie, WY 82070-9721 deep humility and considerable A long standing tradition is being (307) 742-3504 upheld as the 1st Cavalry Division <[email protected]> sorrow that I must announce my resignation as the President Horse Cavalry Detachment gears up to participate in the Inauguration of the 1st Cavalry Division Association effective Saturday, 25 February 2017. Day parade Jan. 20 in Washington, I must say, first of all, that I have enjoyed my association with all of you over D.C. This will be the detachment’s the years…at Reunions, at Chapter meetings, at coffees, at casual b.s. sessions, fifth time participating in the event. and at various activities. My assignments to the 1st Cavalry Division itself and “It’s a tremendous honor to be able my friendships with you have been some of the highpoints of my life. to do this,” Capt. Jeremy Woodard, To my regret, my medical/physical condition precludes me from travelling. -

Lessons-Encountered.Pdf

conflict, and unity of effort and command. essons Encountered: Learning from They stand alongside the lessons of other wars the Long War began as two questions and remind future senior officers that those from General Martin E. Dempsey, 18th who fail to learn from past mistakes are bound Excerpts from LChairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff: What to repeat them. were the costs and benefits of the campaigns LESSONS ENCOUNTERED in Iraq and Afghanistan, and what were the LESSONS strategic lessons of these campaigns? The R Institute for National Strategic Studies at the National Defense University was tasked to answer these questions. The editors com- The Institute for National Strategic Studies posed a volume that assesses the war and (INSS) conducts research in support of the Henry Kissinger has reminded us that “the study of history offers no manual the Long Learning War from LESSONS ENCOUNTERED ENCOUNTERED analyzes the costs, using the Institute’s con- academic and leader development programs of instruction that can be applied automatically; history teaches by analogy, siderable in-house talent and the dedication at the National Defense University (NDU) in shedding light on the likely consequences of comparable situations.” At the of the NDU Press team. The audience for Washington, DC. It provides strategic sup- strategic level, there are no cookie-cutter lessons that can be pressed onto ev- Learning from the Long War this volume is senior officers, their staffs, and port to the Secretary of Defense, Chairman ery batch of future situational dough. The only safe posture is to know many the students in joint professional military of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and unified com- historical cases and to be constantly reexamining the strategic context, ques- education courses—the future leaders of the batant commands. -

Allied Expeditionary Air Force 6 June 1944

Allied Expeditionary Air Force 6 June 1944 HEADQUARTERS ALLIED EXPEDITIONARY AIR FORCE No. 38 Group 295th Squadron (Albemarle) 296th Squadron (Albemarle) 297th Squadron (Albemarle) 570th Squadron (Albemarle) 190th Squadron (Stirling) 196th Squadron (Stirling) 299th Squadron (Stirling) 620th Squadron (Stirling) 298th Squadron (Halifax) 644th Squadron (Halifax) No 45 Group 48th Squadron (C-47 Dakota) 233rd Squadron (C-47 Dakota) 271st Squadron (C-47 Dakota) 512th Squadron (C-47 Dakota) 575th Squadron (C-47 Dakota) SECOND TACTICAL AIR FORCE No. 34 Photographic Reconnaissance Group 16th Squadron (Spitfire) 140th Squadron (Mosquito) 69th Squadron (Wellington) Air Spotting Pool 808th Fleet Air Arm Squadron (Seafire) 885th Fleet Air Arm Squadron (Seafire) 886th Fleet Air Arm Squadron (Seafire) 897th Fleet Air Arm Squadron (Seafire) 26th Squadron (Spitfire) 63rd Squadron (Spitfire) No. 2 Group No. 137 Wing 88th Squadron (Boston) 342nd Squadron (Boston) 226th Squadron (B-25) No. 138 Wing 107th Squadron (Mosquito) 305th Squadron (Mosquito) 613th Squadron (Mosquito) NO. 139 Wing 98th Squadron (B-25) 180th Squadron (B-25) 320th Squadron (B-25) No. 140 Wing 21st Squadron (Mosquito) 464th (RAAF) Squadron (Mosquito) 487t (RNZAF) Squadron (Mosquito) No. 83 Group No. 39 Reconnaissance Wing 168th Squadron (P-51 Mustang) 414th (RCAF) Squadron (P-51 Mustang) 430th (RCAF) Squadron (P-51 Mustang) 1 400th (RCAF) Squadron (Spitfire) No. 121 Wing 174th Squadron (Typhoon) 175th Squadron (Typhoon) 245th Squadron (Typhoon) No. 122 Wing 19th Squadron (P-51 Mustang) 65th Squadron (P-51 Mustang) 122nd Squadron (P-51 Mustang) No. 124 Wing 181st Squadron (Typhoon) 182nd Squadron (Typhoon) 247th Squadron (Typhoon) No. 125 Wing 132nd Squadron (Spitfire) 453rd (RAAF) Squadron (Spitfire) 602nd Squadron (Spitfire) No. -

Volume II March-April 1918 No. 2

re caw STRUKKH Devoted to International Socialism VoL II MARCH—APRIL, 1918 No, 2 The Future of 'She Russian Revolution By SANTERI NUORTEVA Selfdetermination of Nations and Selfdefense B7 KARL LIEBKNECHT Changing Labor Conditions in By FLORENCE KELLEY 15he State in Russia-Old and New Br LEON TROTZKY PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIALIST PUBLICATION SOCIETY, 119 LAFAYETTE ST., N. Y. CITY THE CLASS STRUGGLE Devoted to International Socialism Vd. II MARCH— APRIL, 1918 No. 2 Published by The Socialk Publication Society. 119 Lafayette St.N.Y. City Issued Every Two Months—25^ a Copy; $1.50 a Year EdUoa: LOUIS B. BOUDIN, LOUIS C FRAJNA, LUDWIG LORE CONTENTS VOI.. II MARCH-APRIL, 1918 No. 2 Changing Labor Conditions in Wartime. By Florence Kelley ...... ...... 129 The Land Question in the Russian Revolution. Changing Labor Conditions in Wartime By W. D .............. 143 By FLORENCE KELLEY Forming a War Psychosis. By Dr. John J. Kallen. 161 The Future of the Russian Revolution. By Changes before America entered the War Santeri Nuorteva ........... 171 Since August, 1914, labor conditions in the United States The Tragedy of the Russian Revolution. — Second have been changing incessantly, but the minds of the mass of wage-earners have not kept pace with these changes. Act. By L. B. Boudin ......... 186 Before the war European immigration into the United States Self-determination of Nations and Self-defense. had been, for several years, at the rate of more than a million By Karl Liebknecht. ......... 193 a year, largely from the nations then at war,—Italy and the Germany, the Liberator. By Ludwig Lore. -

Schijfwereld 6 - De Plaagzusters Gratis

SCHIJFWERELD 6 - DE PLAAGZUSTERS GRATIS Auteur: Terry Pratchett Aantal pagina's: 240 pagina's Verschijningsdatum: 2008-07-01 Uitgever: Boekerij EAN: 9789022551189 Taal: nl Link: Download hier Schijfwereld 6 - De plaagzusters Maak je eigen Star Wars kerstverlichting! Figuranten gezocht voor Archeon. Boogschieten à la Katniss Everdeen. Interview met Synthal. Alle Evenementeninterviews Evenementenkalender Evenementennieuws Sfeerverslagen. Jubileumeditie Dutch Comic Con verplaatst naar Elfia Arcen gaat door en nieuw concept: Fairy Nights. De fantasywereld in coronatijd: Castlefest. Home Boeken Databank. Schijfwereld Plaagzusters. Alle boeken van deze auteur. Please enter your comment! Please enter your name here. You have entered an incorrect email address! Top Satirical Books Genre Benders: Comic Fantasy 1. KayStJ's to-read list Read the book and saw the movie Books Read in 1, Speculative Fiction to Read Huxley's reading log Stories Inspired by Other Fiction Shakespeare Quote Titles Retellings of Shakespeare Plays 4. Books You Bought in Survey of Fantasy Classics Bezig met laden The witches of Lancre meddle with the king situation. Saraishelafs Nov 4, Loved it. LoriFox Oct 24, When treachery deprives Lancre of almost all of its. Ravenwood Oct 13, My other favorite so far tied with Mort. Wizard have all the fun, but the witches take the show and run. AnnaBookcritter Sep 15, Vertaler Secondaire auteur sommige edities bevestigd Couton, Patrick Vertaler Secondaire auteur sommige edities bevestigd Imrie, Celia Verteller Secondaire auteur sommige edities bevestigd Imrie, Celia Verteller Secondaire auteur sommige edities bevestigd Kantůrek, Jan Vertaler Secondaire auteur sommige edities bevestigd Kidd, Tom Artiest omslagafbeelding Secondaire auteur sommige edities bevestigd Kirby, Josh Artiest omslagafbeelding Secondaire auteur sommige edities bevestigd Macía, Cristina Vertaler Secondaire auteur sommige edities bevestigd Salmenoja, Margit Vertaler Secondaire auteur sommige edities bevestigd Sweet, Darrell K. -

Order of Battle Changes for Operation Phantom Thunder

BACKGROUNDER #2 Order of Battle for Operation Phantom Thunder Kimberly Kagan, Executive Director and Wesley Morgan, Researcher June 20, 2007 General David Petraeus, commander of Multi-National Forces-Iraq, and Lieutenant General Raymond Odierno, commander of Multi-National Corps-Iraq, launched a coordinated offensive operation on June 15, 2007 to clear al Qaeda strongholds outside of Baghdad. The arrival of the fifth Army “surge” brigade, the Marine Expeditionary Unit, and the combat aviation brigade enabled GEN Petraeus and LTG Odierno to begin this major offensive, named “Operation Phantom Thunder.” Three different U.S. Division Headquarters in different provinces are participating in Phantom Thunder. Multi-National Division-North (Diyala); Multi-National Division-Center (North Babil and Baghdad); and Multi-National Division-West (Anbar). In addition to reinforcing these areas with new troops, LTG Odierno and his division commanders have repositioned some brigades and battalions that were already operating in and around Baghdad. MND-North, Diyala Operation Arrowhead Ripper The core unit in Diyala has been 3rd BCT (Brigade Combat Team), 1st Cavalry Division, which has four battalions plus reinforcements. One of its battalions, 1-12 CAV, has been stationed on FOB Warhorse. A second battalion from the same brigade, the 6-9 ARS, has been operating in Muqdadiya, northeast of Baquba. The 5-73 RSTA (Reconnaissance, Scouting, and Target Acquisition Squadron) has been operating in the river valley northeast of Baquba (in locations such as Zaganiyah). The 5-20 Infantry has been operating in and around southern Baquba. (In addition, MND-N has sent a company from 2-35 Infantry to 5-73 and a company from 1-505 Parachute Infantry Regiment to 6-9 in order to provide those battalions with infantry). -

The Long War (Long Earth) by Terry Pratchett Ebook

The Long War (Long Earth) by Terry Pratchett ebook Ebook The Long War (Long Earth) currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook The Long War (Long Earth) please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Series:::: Long Earth (Book 2)+++Mass Market Paperback:::: 528 pages+++Publisher:::: Harper (January 28, 2014)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 0062068695+++ISBN-13:::: 978-0062068699+++Product Dimensions::::4.2 x 1.2 x 7.5 inches++++++ ISBN10 0062068695 ISBN13 978-0062068 Download here >> Description: The Long War by Terry Pratchett and Stephen Baxter follows the adventures and travails of heroes Joshua Valiente and Lobsang in an exciting continuation of the extraordinary science fiction journey begun in their New York Times bestseller The Long Earth.A generation after the events of The Long Earth, humankind has spread across the new worlds opened up by “stepping.” A new “America”—Valhalla—is emerging more than a million steps from Datum—our Earth. Thanks to a bountiful environment, the Valhallan society mirrors the core values and behaviors of colonial America. And Valhalla is growing restless under the controlling long arm of the Datum government.Soon Joshua, now a married man, is summoned by Lobsang to deal with a building crisis that threatens to plunge the Long Earth into a war unlike any humankind has waged before. The book has the dubious honor of being the second book I have ever stopped reading and not resumed.As others have pointed out, The Long Earth was a far better novel, had good tension and built a great world.