Research Article Multimodality Imaging of the Peripheral Venous System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deep Venous Thrombosis with Suspected Pulmonary Embolism

Thoracic Imaging Peter A. Loud, MD Deep Venous Thrombosis Douglas S. Katz, MD Dennis A. Bruce, MD with Suspected Pulmonary Donald L. Klippenstein, MD Zachary D. Grossman, MD Embolism: Detection with Combined CT Venography Index terms: Computed tomography (CT), 1 angiography, 9*.129142, and Pulmonary Angiography 9*.12915, 9*.12916 Embolism, pulmonary, 60.72 Pulmonary angiography, 944.12914, 944.12915, 944.12916 PURPOSE: To determine the frequency and location of deep venous thrombosis at Veins, thrombosis, 9*.751, 9*.12914 computed tomographic (CT) venography after CT pulmonary angiography in a large series of patients clinically suspected of having pulmonary embolism and to Radiology 2001; 219:498–502 compare the accuracy of CT venography with lower-extremity venous sonography. Abbreviation: MATERIALS AND METHODS: Venous phase images were acquired from the DVT ϭ deep venous thrombosis diaphragm to the upper calves after completion of CT pulmonary angiography in 650 patients (373 women, 277 men; age range, 18–99 years; mean age, 63 years) 1 From the Department of Radiology, to determine the presence and location of deep venous thrombosis. Results of CT Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Elm and Carlton Sts, Buffalo, NY 14263 (P.A.L., venography were compared with those of bilateral lower-extremity venous sonog- D.L.K., Z.D.G.), and the Department raphy in 308 patients. of Radiology, Winthrop University Hospital, Mineola, NY (D.S.K., D.A.B.). RESULTS: A total of 116 patients had pulmonary embolism and/or deep venous From the 1999 RSNA scientific assem- thrombosis, including 27 patients with pulmonary embolism alone, 31 patients with bly. -

Spring Programme 2011

Faculty of Radiologists Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland Combined Spring Meeting 8th & 9 th April 2011 Venue: Castlemartyr Hotel, Co. Cork. Programme Faculty of Radiologists, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland CPD Credits Awarded: 5 Royal College of Radiologists credits are applied for. Friday 8 th April 2011 3.30-4.30pm Registration 4.30-5.30pm Stroke in 2011, Moderator: Dr. Ian Kelly, Waterford Regional Hospital 4.30-5.00pm Acute Stoke Imaging. Dr Noel Fanning, Cork University Hospital, Cork 5.00-5.30pm Stroke: A clinical perspective. Dr. George Pope, John Radcliffe Hospitals, Oxford 5.30-6.30pm Moderator: Dr. Adrian Brady, Dean, Faculty of Radiologists Belfast to Bosnia and Autopsy to Virtopsy Dr. Jack Crane, State Pathologist, NI 8pm Dinner Saturday 9 th April 2011 8.30-9.00am Registration 9.00-10.00am Liver hour. Moderator: Dr John Feeney, AMNCH, Dublin 9.00-9.30am Liver imaging pre metastatectomy. Dr. Peter MacEneaney, Mercy University Hospital, Cork 9.30-10.00am Parenchymal and focal liver biopsy - when and how. Dr Stephen J Skehan St Vincent's University Hospital, Dublin 10.00-11.00am Paediatric Hour. Moderator: Dr. Stephanie Ryan, The Children’s University Hospital Temple Street, Dublin 10.00-10.30am Paediatric Abdominal Emergencies. Dr Eoghan Laffan, The Children’s, University Hospital Temple Street, Dublin 10.30-11.00am Non Accidental Injury. Dr Conor Bogue, Cork University Hospital, Cork 11.00-11.30am Tea/Coffee Break and Poster Exhibition 11.30-12.30pm MSK Hour. Moderator: Dr Orla Buckley, AMNCH, Dublin 11.30-12.00pm Image guided joint interventions. -

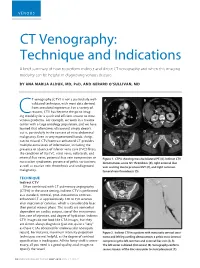

CT Venography: Technique and Indications

VENOUS CT Venography: Technique and Indications A brief summary of how to perform indirect and direct CT venography and when this imaging modality can be helpful in diagnosing venous disease. BY ANA MARIJA ALDUK, MD, PHD, AND GERARD O’SULLIVAN, MD T venography (CTV) is not a particularly well- A B validated technique, with most data derived from anecdotal experience. For a variety of reasons, CTV has become the go-to imag- Cing modality for a quick and efficient answer to most venous problems. For example, we work in a trauma center with a large oncology population, and we have learned that oftentimes ultrasound simply doesn’t cut it, particularly in the context of intra-abdominal C D malignancy. Even in very experienced hands, things can be missed. CTV/contrast-enhanced CT provides multiple extra levels of information, including the presence or absence of inferior vena cava (IVC) filters; the condition of the IVC, renal veins, collaterals, and internal iliac veins; potential iliac vein compression or Figure 1. CTPA showing massive bilateral PE (A). Indirect CTV nutcracker syndromes; presence of pelvic varicosities; demonstrates acute IVC thrombosis (B), right external iliac as well as ovarian vein thrombosis and undiagnosed vein scarring due to previous DVT (C), and right common malignancy. femoral vein thrombosis (D). TECHNIQUE A C Indirect CTV Often combined with CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) in the acute setting, indirect CTV is performed as a standard, nonoral, post–intravenous contrast- enhanced CT at approximately 120 to 150 seconds after injection of contrast, which is considerably later than portal venous phase. -

2Nd Quarter 2001 Medicare Part a Bulletin

In This Issue... From the Intermediary Medical Director Medical Review Progressive Corrective Action ......................................................................... 3 General Information Medical Review Process Revision to Medical Record Requests ................................................ 5 General Coverage New CLIA Waived Tests ............................................................................................................. 8 Outpatient Hospital Services Correction to the Outpatient Services Fee Schedule ................................................................. 9 Skilled Nursing Facility Services Fee Schedule and Consolidated Billing for Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF) Services ............. 12 Fraud and Abuse Justice Recovers Record $1.5 Billion in Fraud Payments - Highest Ever for One Year Period ........................................................................................... 20 Bulletin Medical Policies Use of the American Medical Association’s (AMA’s) Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) Codes on Contractors’ Web Sites ................................................................................. 21 Outpatient Prospective Payment System January 2001 Update: Coding Information for Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) ......................................................................................................................... 93 he Medicare A Bulletin Providers Will Be Asked to Register Tshould be shared with all to Receive Medicare Bulletins and health care -

(MRA) and Magnetic Resonance Venography (MRV) Medical Policy

Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA) and Magnetic Resonance Venography (MRV) Medical Policy The content of this document is used by plans that do not utilize NIA review. Service: Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA) and Magnetic Resonance Venography (MRV) PUM 250-0027-1712 Medical Policy Committee Approval 12/11/2020 Effective Date 01/01/2021 Prior Authorization Needed Yes Description: Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA) and Magnetic Resonance Venography (MRV) use Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technology to produce detailed 2-dimensional or 3- dimensional images of the vascular system and may be tailored to assess arteries or veins. It is often used for vascular conditions where other types of imaging are considered inferior or contraindicated, and to decrease risk of cumulative radiation exposure and often instead of invasive procedures. Indications of Coverage: A. MRA/MRV is considered medically necessary for the anatomical regions listed below when the specific indications or symptoms described are documented: 1. Head/Brain: a. Suspected intracranial aneurysm (ICA) or arteriovenous malformation (AVM). Any of the following: 1. Acute severe headache, severe exertional headache, or sudden onset of explosive headache, in individuals with signs / symptoms highly suggestive of a leaking/ruptured internal carotid artery or arteriovenous malformation. 2. Known subarachnoid hemorrhage or diagnosis of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage with concern for underlying vascular abnormality. 3. Suspected arteriovenous malformation (AVM) or dural AV fistula in an individual with prior indeterminate imaging study 4. Thunderclap headache with question of underlying vascular abnormality AND prior negative workup to include EITHER i. negative brain MRI, OR ii. Negative brain CT and negative lumbar puncture Page 1 of 15 5. -

Optos 200Tx and Heidelberg Spectralis

EXPERIMENTAL AND THERAPEUTIC MEDICINE 21: 19, 2021 Performance evaluation of two fundus oculi angiographic imaging system: Optos 200Tx and Heidelberg Spectralis SHUANG LI, JING‑JING WANG, HONG‑YANG LI, WEI WANG, MENG TIAN, XU‑QIANG LANG and KANG WANG Department of Ophthalmology, Beijing Friendship Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing 100050, P.R. China Received December 15, 2018; Accepted October 29, 2019 DOI: 10.3892/etm.2020.9451 Abstract. The present study aimed to compare the imaging Introduction performance of two ultra‑wide‑field fluorescein angiog‑ raphy imaging systems, namely the OptosOptomap 200Tx Ultra‑wide‑field fluorescein angiography (UWFA) is a novel (Optos 200Tx) and the Heidelberg Spectralis (Spectralis). A total technology that has developed rapidly in recent years (1,2). of 18 patients (36 eyes) underwent angiography using the two As numerous pathological changes of fundus diseases occur systems at the Department of Ophthalmology, Beijing Friendship at the edge of the retina, the limitation of imaging leads to Hospital (Beijing, China) between January and June 2017. The insufficient diagnosis or underestimation of the severity of the images were obtained as a single shot centered on the macula. disease (3,4). Therefore, clear imaging of the edge of the retina The total area and area within each of four visualized quadrants is important for the diagnosis, monitoring and prognostication were calculated and compared. The averages of the total and of patients with ocular fundus diseases. The traditional fundus individual quadrant area captured by the Optos 200Tx were fluorescein angiography system may only provide a vision field all larger than those obtained with the Spectralis (P<0.05). -

Initial Observations Comparing MDCT and 3.0T MRI Findings with Autopsy Findings

Utility of Postmortem Autopsy via Whole- Body Imaging: Initial Observations Comparing MDCT and 3.0T MRI Findings with Autopsy Findings Jang Gyu Cha, MD1 Dong Hun Kim, MD1 Objective: We prospectively compared whole-body multidetector computed Dae Ho Kim, MD2 tomography (MDCT) and 3.0T magnetic resonance (MR) images with autopsy Sang Hyun Paik, MD1 findings. Jai Soung Park, MD1 Materials and Methods: Five cadavers were subjected to whole-body, 16- Seong Jin Park, MD1 channel MDCT and 3.0T MR imaging within two hours before an autopsy. A radi- Hae Kyung Lee, MD1 ologist classified the MDCT and 3.0T MRI findings into major and minor findings, Hyun Sook Hong, MD1 which were compared with autopsy findings. 3 Duek Lin Choi, MD Results: Most of the imaging findings, pertaining to head and neck, heart and 4 Kyung Moo Yang, MD vascular, chest, abdomen, spine, and musculoskeletal lesions, corresponded to 4 Nak Eun Chung, MD autopsy findings. The causes of death that were determined on the bases of 4 Bong Woo Lee, MD MDCT and 3.0T MRI findings were consistent with the autopsy findings in four of 4 Joong Seok Seo, MD five cases. CT was useful in diagnosing fatal hemorrhage and pneumothorax, as well as determining the shapes and characteristics of the fractures and the direc- Index terms: tion of external force. MRI was effective in evaluating and tracing the route of a Computed tomography (CT) metallic object, soft tissue lesions, chronicity of hemorrhage, and bone bruises. Magnetic resonance (MR) Whole-body imaging Conclusion: A postmortem MDCT combined with MRI is a potentially powerful Forensic autopsy tool, providing noninvasive and objective measurements for forensic investiga- DOI:10.3348/kjr.2010.11.4.395 tions. -

Coders' Desk Reference for ICD-10-PCS Procedures

2 0 2 DESK REFERENCE 1 ICD-10-PCS Procedures ICD-10-PCS for DeskCoders’ Reference Coders’ Desk Reference for ICD-10-PCS Procedures Clinical descriptions with answers to your toughest ICD-10-PCS coding questions Sample 2021 optum360coding.com Contents Illustrations ..................................................................................................................................... xi Introduction .....................................................................................................................................1 ICD-10-PCS Overview ...........................................................................................................................................................1 How to Use Coders’ Desk Reference for ICD-10-PCS Procedures ...................................................................................2 Format ......................................................................................................................................................................................3 ICD-10-PCS Official Guidelines for Coding and Reporting 2020 .........................................................7 Conventions ...........................................................................................................................................................................7 Medical and Surgical Section Guidelines (section 0) ....................................................................................................8 Obstetric Section Guidelines (section -

APG Regulations

FINAL as of 8/22/08 Pursuant to the authority vested in the Commissioner of Health by Section 2807(2-a) of the Public Health Law, Part 86 of Title 10 of the Official Compilation of Codes, Rules and Regulations of the State of New York, is amended by adding a new Subpart 86-8, to be effective upon filing with the Secretary of State, to read as follows: SUBPART 86-8 OUTPATIENT SERVICES: AMBULATORY PATIENT GROUP (Statutory authority: Public Health Law § 2807(2-a)(e)) Sec. 86-8.1 Scope 86-8.2 Definitions 86-8.3 Record keeping, reports and audits 86-8.4 Capital reimbursement 86-8.5 Administrative rate appeals 86-8.6 Rates for new facilities during the transition period 86-8.7 APGs and relative weights 86-8.8 Base rates 86-8.9 Diagnostic coding and rate computation 86-8.10 Exclusions from payment 86-8.11 System updating 86-8.12 Payments for extended hours of operation § 86-8.1 Scope (a) This Subpart shall govern Medicaid rates of payments for ambulatory care services provided in the following categories of facilities for the following periods: (1) outpatient services provided by general hospitals on and after December 1, 2008; (2) emergency department services provided by general hospitals on and after January 1, 2009; (3) ambulatory surgery services provided by general hospitals on and after December 1, 2008; (4) ambulatory services provided by diagnostic and treatment centers on and after March 1, 2009; and (5) ambulatory surgery services provided by free-standing ambulatory surgery centers on and after March 1, 2009. -

Indocyanine Green Fluorography in Plastic Surgery and Microvascular Surgery

48 The Open Surgical Oncology Journal, 2010, 2, 48-56 Open Access Indocyanine Green Fluorography in Plastic Surgery and Microvascular Surgery Ryuichi Azuma*,1, Megumi Takikawa1, Shinichirou Nakamura1, Kaoru Sasaki1, Satoshi Yanagibayashi1, Naoto Yamamoto1, Tomoharu Kiyosawa1 and Yuji Morimoto2 1Department of Plastic Surgery, Natinal Defense Medical College, Japan 2Department of Integrative Physiology and Bio-Nano Medicine National Defense Medical College, Japan Abstract: Indocyanine green (ICG) fluorography which is used to visualize the arteries, veins, and lymphatic vessels through the skin surface has recently been developed. This article includes an overview of our clinical experiences as well as descriptions of the latest knowledge on the utilization of ICG fluorography in the fields of plastic surgery and microvascular surgery. Imaging of the Capillary Blood Flow: To predict the future survival and necrosis, ICG fluorography is useful in various situations such as to examine injured limbs, skin flaps with a poor blood flow or ischemic limbs due to arteriosclerosis obliterans. Imaging of the Arteries: Practical pictures of a subcutaneous artery can be obtained for preoperative evaluations of the nutrient vessels of a skin flap and the blood flow within a skin flap. It is particularly useful for planning the use of a perforator-based flap. Imaging of the Lymphatic Vessels: ICG lymphography makes it possible to easily detect the functional lymphatic vessels in lymphaticovenous anastomosis for lymphedema of the extremities after either a surgical lymph node dissection or radiotherapy. Imaging of the Veins: With near-infrared skin imaging after the systemic administration of ICG, a clear picture of the subcutaneous veins, approximately 1 to 2 cm from the surface, can be obtained. -

Consent for Adrenal Venography and Adrenal Vein Blood Sampling

University of Pennsylvania Health System Department of Radiology Division of Vascular And Interventional Radiology Consent for Adrenal Venography and Adrenal Vein Blood Sampling INTRODUCTION: RISKS: Your physician has requested that you undergo an Risks associated with the procedure include, but are not adrenal vein blood sampling to determine the cause limited to, pain or discomfort at the catheter insertion of the elevated hormone aldosterone in your blood. site, bleeding at the site, injury to a blood vessel, Based on the findings of this study, a decision infection which may result in an infection of the blood between medical therapy and surgery can be made. stream, the development of a blood clot (embolization), We are asking you to read and sign this form so that and stroke. Risks associated with the x-ray contrast we can be sure you understand the procedure and material include an allergic reaction and reduced kidney potential benefits, along with the associated function. The medications used for the moderate potential risks, complications, alternatives, the sedation are associated with the risks of aspiration likelihood of achieving the goals, and the (inhaling food or liquid into your lungs) or respiratory recuperative process. Please ask questions about depression. In addition to these potential risks anything on this form that you do not understand. associated with the procedure, the x-ray contrast material, and the moderate sedation medications, there may PROCEDURE: be other unpredictable risks including death. An adrenal venogram involves the placement of a (Complete this paragraph if applicable or document “NA”) plastic tube (catheter) into a vein in your leg near the Due to your additional medical history of hip. -

Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography in Papilledema Compared with Pseudopapilledema

Eye Movements, Strabismus, Amblyopia and Neuro-Ophthalmology Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography in Papilledema Compared With Pseudopapilledema Masoud Aghsaei Fard,1 Alireza Sahraiyan,1 Jalil Jalili,2 Marjane Hejazi,2 Yanin Suwan,3 Robert Ritch,4 and Prem S. Subramanian5 1Farabi Eye Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Science, Tehran, Iran 2Department of Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering, Research Center for Molecular and Cellular in Imaging, School of Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Science, Tehran, Iran 3Department of Ophthalmology, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand 4Einhorn Clinical Research Center, New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai, New York, New York, United States 5Department of Ophthalmology, University of Colorado, School of Medicine, Aurora, Colorado, United States Correspondence: Masoud Aghsaei PURPOSE. The purpose of this study is to evaluate differences in optical coherence tomography Fard, Qazvin Square, Farabi Eye angiography (OCT-A) findings between patients with papilledema and pseudopapilledema. Hospital, Tehran University of Medi- cal Science, Tehran 13366, Iran; METHODS. In this prospective, comparative study, 41 eyes of 21 subjects with papilledema, 27 [email protected]. eyes of 15 subjects with pseudopapilledema, and 44 eyes of 44 healthy normal subjects were included and were imaged using OCT-A. In addition to peripapillary total vasculature maps Submitted: August 4, 2018 Accepted: November 25, 2018 obtained with commercial vessel density mapping, major vessel removal using customized image analysis software was also used to measure whole image capillary density and Citation: Fard MA, Sahraiyan A, Jalili J, peripapillary capillary density (PCD). Peripapiilary retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) and et al. Optical coherence tomography macular ganglion cell complex (GCC) were recorded.