Yoga and Yoga Therapy Georg Feuerstein, Ph.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prescribing Yoga to Supplement and Support Psychotherapy

12350-11_CH10-rev.qxd 1/11/11 11:55 AM Page 251 10 PRESCRIBING YOGA TO SUPPLEMENT AND SUPPORT PSYCHOTHERAPY VINCENT G. VALENTE AND ANTONIO MAROTTA As the flame of light in a windless place remains tranquil and free from agitation, likewise, the heart of the seeker of Self-Consciousness, attuned in Yoga, remains free from restlessness and tranquil. —The Bhagavad Gita The philosophy of yoga has been used for millennia to experience, examine, and explain the intricacies of the mind and the essence of the human psyche. The sage Patanjali, who compiled and codified the yoga teachings up to his time (500–200 BCE) in his epic work Yoga Darsana, defined yoga as a method used to still the fluctuations of the mind to reach the central reality of the true self (Iyengar, 1966). Patanjali’s teachings encour- age an intentional lifestyle of moderation and harmony by offering guidelines that involve moral and ethical standards of living, postural and breathing exercises, and various meditative modalities all used to cultivate spiritual growth and the evolution of consciousness. In the modern era, the ancient yoga philosophy has been revitalized and applied to enrich the quality of everyday life and has more recently been applied as a therapeutic intervention to bring relief to those experiencing Copyright American Psychological Association. Not for further distribution. physical and mental afflictions. For example, empirical research has demon- strated the benefits of yogic interventions in the treatment of depression and anxiety (Khumar, Kaur, & Kaur, 1993; Shapiro et al., 2007; Vinod, Vinod, & Khire, 1991; Woolery, Myers, Sternlieb, & Zeltzer, 2004), schizophrenia (Duraiswamy, Thirthalli, Nagendra, & Gangadhar, 2007), and alcohol depen- dence (Raina, Chakraborty, Basit, Samarth, & Singh, 2001). -

Bio Data DR. JAYADEVA YOGENDRA

4NCE Whenever we see Dr. Jayadeva, we are reminded of Patanjali's Yoga Sutra: "When one becomes disinterested even in Omniscience One attains perpetual discriminative enlightenment from which ensues the concentration known as Dharmamegha (Virtue Pouring Cloud)". - Yoga Sutra 4.29 He represents a mind free of negativity and totally virtuous. Whoever comes in contact with him will only be blessed. The Master, Dr Jayadeva, was teaching in the Yoga Teachers Training class at The Yoga Institute. After the simple but inspiring talk, as usual he said. IIAnyquestions?" After many questions about spirituality and Yoga, one young student asked, "Doctor Sahab how did you reach such a high state of development?" In his simple self-effacing way he did not say anything. Theyoung enthusiast persisted, 'Please tell us.II He just said, "Adisciplined mind." Here was the definition of Yoga of Patanjali, "roqa Chitta Vritti Nirodha" Restraining the modifications of the mind is Yoga. Naturally the next sutra also followed "Tada Drashtu Svarupe Avasthanam". "So that the spirit is established in its own true nature." Recently, there was a function to observe the 93fd Foundation Day of The Yoga Institute which was founded by Dr. Jayadeva's father, Shri Yogendraji - the Householder Yogi and known as "the Father of Modern Yoga Renaissance". At the end of very "learned" inspiring presentations, the compere requested Dr.Jayadeva." a man of few words" to speak. Dr.Jayadeva just said,"Practise Yoga.II Top: Mother Sita Devi Yogendra, Founder Shri Yogendraji, Dr. Jayadeva Yogendra, Hansaji Jayadeva Yogendra, Patanjali Jayadeva Yogendra. Bottom: Gauri Patanjali Yogendra, Soha Patanjali Yogendra, Dr. -

University of California Riverside

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Choreographers and Yogis: Untwisting the Politics of Appropriation and Representation in U.S. Concert Dance A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Critical Dance Studies by Jennifer F Aubrecht September 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Jacqueline Shea Murphy, Chairperson Dr. Anthea Kraut Dr. Amanda Lucia Copyright by Jennifer F Aubrecht 2017 The Dissertation of Jennifer F Aubrecht is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I extend my gratitude to many people and organizations for their support throughout this process. First of all, my thanks to my committee: Jacqueline Shea Murphy, Anthea Kraut, and Amanda Lucia. Without your guidance and support, this work would never have matured. I am also deeply indebted to the faculty of the Dance Department at UC Riverside, including Linda Tomko, Priya Srinivasan, Jens Richard Giersdorf, Wendy Rogers, Imani Kai Johnson, visiting professor Ann Carlson, Joel Smith, José Reynoso, Taisha Paggett, and Luis Lara Malvacías. Their teaching and research modeled for me what it means to be a scholar and human of rigorous integrity and generosity. I am also grateful to the professors at my undergraduate institution, who opened my eyes to the exciting world of critical dance studies: Ananya Chatterjea, Diyah Larasati, Carl Flink, Toni Pierce-Sands, Maija Brown, and rest of U of MN dance department, thank you. I thank the faculty (especially Susan Manning, Janice Ross, and Rebekah Kowal) and participants in the 2015 Mellon Summer Seminar Dance Studies in/and the Humanities, who helped me begin to feel at home in our academic community. -

YOGA. Physiology, Psychosomatics, Bioenergetics

CONTENTS PREFACE .............................................................................................................................................................11 What is Yoga ...............................................................................................................................................11 Hatha in the system of Yoga .................................................................................................................15 HUMAN ENERGY STRUCTURE ...................................................................................................................17 Energy bodies ............................................................................................................................................17 Human’s Сhakral System .......................................................................................................................18 History ...................................................................................................................................................18 Physiological aspects of chakras ..................................................................................................20 Psychological aspects of chakras .................................................................................................21 Chakra’s strength ..............................................................................................................................21 Maturity of chakra. Openness and closeness of chakra ......................................................24 -

Yoga: Intermediate 1 Credit, FALL 2018 T/TR 7:30Am - 8:45Am / RAC 2201 – Fairfax Campus

George Mason University College of Education and Human Development Physical Activity for Lifetime Wellness RECR 187 003 – Yoga: Intermediate 1 Credit, FALL 2018 T/TR 7:30am - 8:45am / RAC 2201 – Fairfax Campus Faculty Name: Chris Liss Office Hours: By Appointment Office Location: TBA Office Phone: 703-459-3620 Email Address: [email protected] Prerequisites/Corequisites - RECR 186 or permission of the instructor University Catalog Course Description Emphasizes mastery of yoga asanas (postures) and pranayama (breathing techniques) to enhance physical and mental concentration. Focuses on 10 new yoga poses and practice of the complete Sun Salutation. Course Overview Readings, lectures, demonstrations and class participation will be used to analyze the practice of yoga asana and yoga philosophy. •Students with injuries or pre-existing conditions that may affect performance must inform the instructor. •Students with specific medication conditions, limited flexibility or injuries will learn appropriate modifications of poses for their own practices. •All e-mail communication will be through GMU e-mail system – the Patriot Web Site. •Students are requested to bring their own yoga mat to class. •Comfortable stretch clothing are required. No street clothes may be worn. Course Delivery Method: Face-to-face Learner Outcomes or Objectives This course is designed to enable students to do the following: 1. Demonstrate at least 25 asanas, including proper alignment. 1 Last revised February 2018 2. Identify the poses and demonstrate proficiency in “Sun Salutation” (Surya Namaskar); 3. Classify asanas as to their types. 4. Name the benefits and contra-indications of asanas. 5. Develop proficiency in the practice of three types of pranayama 6. -

Yoga and Education (Grades K-12)

Yoga and Education (Grades K-12) Compiled by: Trisha Lamb Last Revised: April 27, 2006 © International Association of Yoga Therapists (IAYT) 2005 International Association of Yoga Therapists P.O. Box 2513 • Prescott • AZ 86302 • Phone: 928-541-0004 E-mail: [email protected] • URL: www.iayt.org The contents of this bibliography do not provide medical advice and should not be so interpreted. Before beginning any exercise program, see your physician for clearance. NOTE: For Yoga classes and other undergraduate and graduate Yoga-related studies in the university setting, s ee the “Undergraduate and Graduate Programs” bibliography. “The soul is the root. The mind is the trunk. The body constitutes the leaves. The leaves are no doubt important; they gather the sun’s rays for the entire tree. The trunk is equally important, perhaps more so. But if the root is not watered, neither will survive for long. “Education should start with the infant. Even the mother’s lullaby should be divine and soul elevating, infusing in the child fearlessness, joy, peace, selflessness and godliness. “Education is not the amassing of information and its purpose is not mere career hunting. It is a means of developing a fully integrated personality and enabling one to grow effectively into the likeness of the ideal that one has set before oneself. Education is a drawing out from within of the highest and best qualities inherent in the individual. It is training in the art of living.” —Swami Satyananda Saraswati Yoga, May 2001, p. 8 “Just getting into a school a few years ago was a big deal. -

1.3.1-YSH-456(Envi)

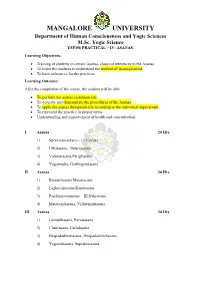

MANGALORE UNIVERSITY Department of Human Consciousness and Yogic Sciences M.Sc. Yogic Science YSP456 PRACTICAL – IV: ASANAS. Learning Objectives: • Training of students in certain Asanas, classical references to the Asanas. • To make the students to understand the method of Asana practice. • To have references for the practices. Learning Outcome: After the completion of the course, the student will be able – • To perform the asanas systematically. • To describe and demonstrate the procedures of the Asanas. • To apply the asanas therapeutically according to the individual requirement. • To represent the practice in proper terms. • Understanding and improvement of health and concentration. I Asanas 24 Hrs 1) Surya namaskara – 12 vinyasa 2) Utkatasana, Natarajasana 3) Vatayanasana,Parighasana 4) Yogamudra, Garbhapindasana II Asanas 24 Hrs 1) Kraunchasana,Mayurasana 2) Laghuvajrasana,Kapotasana 3) Paschimottanasana – III,Nakrasana 4) Matsyendrasana, Vishwamitrasana III Asanas 24 Hrs 1) Gomukhasana, Parvatasana 2) Chakrasana, Garudasana 3) Ekapadashirshasana, Dwipadashirshasana 4) Yoganidrasana, Suptakonasana REFERENCE BOOKS 1. Swami Digambarji(1997), Hathayoga pradeepika, SMYM Samiti, Kaivalyadhama, Lonavala, Pune - 410403 2. Swami Digambarji(1997), Gheranda Samhita, SMYMSamiti, Kaivalyadhama, Lonavala - 410403. 3. Swami Omananda Teertha, Patanjala Yoga Pradeepa, Gita Press, Gorakhpur-273005 4. JoisPattabhi (2010), Yoga mala – Part I, North Point Press, A Division ofFarrar, Straus and Giroux, 18 west 18the street, New York 10011. 5. B.K.S.Iyangar (1966), Light on Yoga .Harper Collins publication, 77- 85Fulham Palace road, London W6 8JB. 6. B.K.S.Iyangar(1999), Light on Pranayama,HarperCollins,New Delhi,-201307 7. Swami SatyanandaSaraswati(1997), Asana, Pranayama, Mudra, Bandha, Bihar School of Yoga, Munger-811201 8. Swami Geetananda, Bandhas & Mudras, Anandashrama, Pondicherry-605104 9. -

A SURVEY of YOUTH YOGA CURRICULUMS a Dissertation

A SURVEY OF YOUTH YOGA CURRICULUMS A Dissertation Submitted to The Temple University Graduate Board in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Robin A. Lowry August, 2011 Examining Committee Members: Ricky Swalm, Advisory Chair, Kinesiology Michael Sachs, Kinesiology Catherine Schifter, Education Jay Segal, Public Health ii © Copyright By Robin A. Lowry 2011 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT A SURVEY OF YOUTH YOGA CURRICULUMS By Robin A. Lowry Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2011 Doctoral Advisory Committee Chair: Ricky Swalm, Ph. D. Introduction: Yoga is increasingly recommended for the K-12 population as a health intervention, a Physical Education activity, and for fun. What constitutes Yoga however, what is taught, and how it is taught, is variable. The purpose of this study was to survey Youth Yoga curriculums to identify content, teaching strategies, and assessments; dimensions of wellness addressed; whether national Health and Physical Education (HPE) standards were met; strategies to manage implementation fidelity; and shared constructs between Yoga and educational psychology. Methods: A descriptive qualitative design included a preliminary survey (n = 206) and interview (n = 1), questionnaires for curriculum developers (n = 9) and teachers (n = 5), interviews of developers and teachers (n = 3), lesson observations (n= 3), and a review of curriculum manuals. Results: Yoga content was adapted from elements associated with the Yoga Sutras but mostly from modern texts, interpretations, and personal experiences. Curriculums were not consistently mapped, nor elements defined. Non-Yoga content included games, music, and storytelling, which were used to teach Yoga postures and improve concentration, balance, and meta-cognitive skills. -

Yoga and Psychology and Psychotherapy

Yoga and Psychology and Psychotherapy Compiled by: Trisha Lamb Last Revised: April 27, 2006 © 2004 by International Association of Yoga Therapists (IAYT) International Association of Yoga Therapists P.O. Box 2513 • Prescott • AZ 86302 • Phone: 928-541-0004 E-mail: [email protected] • URL: www.iayt.org The contents of this bibliography do not provide medical advice and should not be so interpreted. Before beginning any exercise program, see your physician for clearance. “How is the field of psychotherapy to become progressively more informed by the infinite wisdom of spirit? It will happen through individuals who allow their own lives to be transformed—their own inner source of knowing to be awakened and expressed.” —Yogi Amrit Desai NOTE: See also the “Counseling” bibliography. For eating disorders, please see the “Eating Disorders” bibliography, and for PTSD, please see the “PTSD” bibliography. Books and Dissertations Abegg, Emil. Indishche Psychologie. Zürich: Rascher, 1945. [In German.] Abhedananda, Swami. The Yoga Psychology. Calcutta: Ramakrishna Vedanta Math, 1960, 1983. “This volume comprises lectures delivered by Swami Abhedananda before a[n] . audience in America on the subject of [the] Yoga-Sutras of Rishi Patanjali in a systematic and scientific manner. “The Yoga Psychology discloses the secret of bringing under control the disturbing modifications of mind, and thus helps one to concentrate and meditate upon the transcendental Atman, which is the fountainhead of knowledge, intelligence, and bliss. “These lectures constitute the contents of this memorial volume, with copious references and glossaries of Vyasa and Vachaspati Misra.” ___________. True Psychology. Calcutta: Ramakrishna Vedanta Math, 1982. “Modern Psychology does not [address] ‘a science of the soul.’ True Psychology, on the other hand, is that science which consists of the systematization and classification of truths relating to the soul or that self-conscious entity which thinks, feels and knows.” Agnello, Nicolò. -

Modern Transnational Yoga: a History of Spiritual Commodification

Sacred Heart University DigitalCommons@SHU Master of Arts in Religious Studies (M.A.R.S. Theses) Philosophy, Theology and Religious Studies 8-2010 Modern Transnational Yoga: A History of Spiritual Commodification Jon A. Brammer Sacred Heart University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/rel_theses Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, and the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Brammer, Jon A., "Modern Transnational Yoga: A History of Spiritual Commodification" (2010). Master of Arts in Religious Studies (M.A.R.S. Theses). 29. https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/rel_theses/29 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy, Theology and Religious Studies at DigitalCommons@SHU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Arts in Religious Studies (M.A.R.S. Theses) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@SHU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Modern Transnational Yoga: A History of Spiritual Commodification Master's Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Religious Studies at Sacred Heart University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Religious Studies Jon A. Brammer August 2010 This thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Religious Studies Christel J. Manning, PhD., Professor of Religious Studies - ^ G l o Date Permission for reproducing this text, in whole or in part, for the purpose of individual scholarly consultation or other educational purposes is hereby granted by the author. This permission is not to be interpreted as granting publication rights for this work or otherwise placing it in the public domain. -

And Total Health January 2017

JOURNAL OF THE YOGA INSTITUTE FIRST ISSUED IN 1933 VOL LXI NO.6 PAGES 32 I EMAG YOGA AND TOTAL HEALTH JANUARY 2017 A TRIBUTE TO LIFE AND WELL BEING 98YEARS OF YOGA 01 We lead our life but are we thinking about life itself, the purpose of life? Who am I? Why am I here in this universe? What are my duties? Many questions, but unfortunately our attention does not go that way - we are too busy with our day to day work. Every single practice in yoga points to that direction. When we sit in Sukhasana, the mind can get quiet. In a quiet mood, some clarity can occur, some thinking can happen. These are opportunities during the day when we get such a chance. We have to consider whether we are utilizing such opportunities. We are too busy with our day to day work, we do not have any time to ourselves - this has been going on all our life and it will remain. But in the midst of all this, isn’t it our duty also to understand a little more about life? Or should we just keep carrying on like animals - eat, drink and be merry? This is something that can be considered. Great people, who were respected, were able to think a little more, think a little deeper and improve their life. They were able to help others also as a result. We can do that, but we never think on these things. We just think on continuously earning, eating and enjoying. Publisher, Yoga and Total Health 2 YOGA AND TOTAL HEALTH • January 2017 YOGA AND TOTAL HEALTH • January 2017 Contents 4 98th Foundation Day of The Yoga Institute - A Report 6 Letters to the Editor 7 Hatha Yoga Pradipika 8 Rusted Thinking - Dr. -

Josephine Rathbone and Corrective Physical Education

Yoga Comes to American Physical Education: Josephine Rathbone and Corrective Physical Education P a t r ic ia V e r t in s k y 1 School of Kinesiology University o f British Columbia Around the turn-of-the-twentieth-century yoga took on an American mantle, developing into India’s first “global brand" of physical culture. Physical educa tors became implicated in this transnational exchange adopting aspects of yoga into their programs and activities, though there has been an insufficient attempt to piece together the sum and pattern of their intersecting influences. This paper explores how adopted Eastern cultural practices such as yoga gained traction on American shores and entered the fabric of everyday and institutional life, in cluding the curricula of higher education in the late nineteenth and early de cades of the twentieth century. It then describes how American physical educa tor Josephine L Rathbone came to draw inspiration and knowledge from Indian gurus about the yoga postures she would incorporate in the first and rather significant program o f corrective physical education at Teachers College, Colum bia University during the 1930s and 1940s. As an early pioneer of the evolu tion o f Ling's medical gymnastics into a therapeutic stream o f physical activity which formed an important branch o f physical education, Rathbone was in strumental in maintaining a critical link with physical therapy and medicine, 'Correspondence to [email protected]. facilitating transnational connections and networks while pushing open a ¿loor to mind-body practices from the east. Her project was a small but illuminating aspect o f the shifting spaces o f "bodies in contact” in cross-cultural encounters and complex imperial networks emerging from "modernities" in both East and West.