Josephine Rathbone and Corrective Physical Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum, Instruction, and Theoretical Support (Top Left, Middle, Learning

SECTION I Curriculum, Instruction, and Theoretical Support (top left, middle, bottom right) Courtesy of John Dolly; (top right) © Jones & Bartlett Learning. Photographed by Christine Myaskovsky; (bottom left) © Jones & Bartlett Learning. Photographed by Sarah Cebulski. by Photographed left) © Jones & Bartlett (bottom Learning. Myaskovsky; Christine by Photographed © Jones & Bartlett right) of John Dolly; Courtesy (top right) bottom Learning. middle, left, (top n this section, we begin in Chapters 1 through 3 by describing the goals, national standards, and significance of physical education, including a brief history of this Ifield, and then provide an overview of the movement approach that constitutes the curricular and instructional model presented in this text. In Chapters 4, 5, and 9, we describe the development, learning, and motivation theories that support our approach. We describe instruction in Chapters 6, 7, 8, 10, and 13, thereby link- ing instruction to how children learn and develop. Chapters 11 and 12 discuss teaching social responsibility, emotional goals, and respecting and valuing diver- sity. Planning, assessment, and their links to national standards are discussed in Chapters 14 and 15. Section I is followed by descriptions of the content of the curricular and instructional model, including the sample lesson plans presented in Sections II, III, and IV. As part of these discussions, we link the content to the theoretical support, national standards, and instructional methods discussed in Section I. 9781284103762_CH01_PASS02.indd 1 27/10/15 9:21 am 9781284103762_CH01_PASS02.indd 2 27/10/15 9:21 am CHAPT ER Physical Education Goals, Significance, and National Standards (top left) © Jones & Bartlett Learning. Photographed by Christine Myaskovsky; (right) © Jones & Bartlett Learning. -

University of California Riverside

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Choreographers and Yogis: Untwisting the Politics of Appropriation and Representation in U.S. Concert Dance A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Critical Dance Studies by Jennifer F Aubrecht September 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Jacqueline Shea Murphy, Chairperson Dr. Anthea Kraut Dr. Amanda Lucia Copyright by Jennifer F Aubrecht 2017 The Dissertation of Jennifer F Aubrecht is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I extend my gratitude to many people and organizations for their support throughout this process. First of all, my thanks to my committee: Jacqueline Shea Murphy, Anthea Kraut, and Amanda Lucia. Without your guidance and support, this work would never have matured. I am also deeply indebted to the faculty of the Dance Department at UC Riverside, including Linda Tomko, Priya Srinivasan, Jens Richard Giersdorf, Wendy Rogers, Imani Kai Johnson, visiting professor Ann Carlson, Joel Smith, José Reynoso, Taisha Paggett, and Luis Lara Malvacías. Their teaching and research modeled for me what it means to be a scholar and human of rigorous integrity and generosity. I am also grateful to the professors at my undergraduate institution, who opened my eyes to the exciting world of critical dance studies: Ananya Chatterjea, Diyah Larasati, Carl Flink, Toni Pierce-Sands, Maija Brown, and rest of U of MN dance department, thank you. I thank the faculty (especially Susan Manning, Janice Ross, and Rebekah Kowal) and participants in the 2015 Mellon Summer Seminar Dance Studies in/and the Humanities, who helped me begin to feel at home in our academic community. -

College": Collection

The Woman's College of The University of North Carolina LIBRARY COLLEGE": COLLECTION Gift of Delore* .lean Wertz A COMPARISON OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION IN GERMANY AND AMERICA FROM THE YEARS 1860-1930 by Delores Jean Wertz A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Physical Education Greensboro July, 1963 Approved by APPROVAL SHEET This thesis has been approved by the following committee of the Faculty of the Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Greensboro, North Carolina. Thesis ' ]„ '/' f r Director y;, ,;■:>■/ ' ( • if- Oral Examination C" Committee Members C ^jl ■ ■' ',' ' s. \ ■ . ■' . o (J^Ky^ , fc*Ju,i>.«** Vr' Date of Examination HERTZ, DELORES JEAN. A Comparison of Physical Education in Germany and America From the Years 1860-1930. (1963) Directed by: Dr. Rosemary McGee pp:82 A comparison was made of the development of the physical education movement in Germany and America from i860 to 1930. This writer believes that American physical education and German Leibeserziehung are reflections of the political and social attitudes of these two countries. A study was made of the political situation of both countries during this era. The rich cultural heritage and the uneducated political attitude of the Germans were strikingly different from the democracy of the common man in America and the American individualism which were creating a new culture. Socially the current in Germany flowed with the authoritative leaders and was mirrored in the literature. The literature included the extremes of the spirit of the humanity of Goethe to the Germanity of Jahn. -

'Freaky:' an Exploration of the Development of Dominant

From ‘Classical’ To ‘Freaky:’ an Exploration of the Development of Dominant, Organised, Male Bodybuilding Culture Dimitrios Liokaftos Department of Sociology, Goldsmiths, University of London Submitted for the Degree of PhD in Sociology February 2012 1 Declaration: The work presented in this thesis is my own. Dimitrios Liokaftos Signed, 2 Abstract Through a combination of historical and empirical research, the present thesis explores the development of dominant, organized bodybuilding culture across three periods: early (1880s-1930s), middle (1940s-1970s), and late (1980s-present). This periodization reflects the different paradigms in bodybuilding that the research identifies and examines at the level of body aesthetic, model of embodied practice, aesthetic of representation, formal spectacle, and prevalent meanings regarding the 'nature' of bodybuilding. Employing organized bodybuilding displays as the axis for the discussion, the project traces the gradual shift from an early bodybuilding model, represented in the ideal of the 'classical,' 'perfect' body, to a late-modern model celebrating the 'freaky,' 'monstrous' body. This development is shown to have entailed changes in notions of the 'good' body, moving from a 'restorative' model of 'all-around' development, health, and moderation whose horizon was a return to an unsurpassable standard of 'normality,' to a technologically-enhanced, performance- driven one where 'perfection' assumes the form of an open-ended project towards the 'impossible.' Central in this process is a shift in male identities, as the appearance of the body turns not only into a legitimate priority for bodybuilding practitioners but also into an instance of sport performance in bodybuilding competition. Equally central, and related to the above, is a shift from a model of amateur competition and non-instrumental practice to one of professional competition and extreme measures in search of the winning edge. -

About the Book: About the Author/Illustrator: About

A Standards-aligned Educator’s Guide for Grades 2-3 Strong As Sandow: How Eugen Sandow Became the Strongest Man on Earth LittleAbout Friedrich the Muller book: was a puny weakling who longed to be athletic and Age Range: 6-9 strong like the ancient Roman gladiators. He exercised and exercised. But he Grade Level: 2-3 was still puny. Hardcover: 40 pages As a young man, he found himself under the tutelage of a professional body Publisher: Charlesbridge builder. Friedrich worked and worked. He changed his name to Eugen ISBN: 978-1-58089-628-3 Sandow and he got bigger and stronger. Everyone wanted to become “as E-book ISBN: 978-1-60734-886-3 strong as Sandow.” AboutDon Tate is the author author/illustrator: and illustrator of Poet: The Remarkable Story of George Moses Horton (Peachtree), for which he received the Ezra Jack Keats New Writer Award. He received the Ezra Jack Keats New Writer Honor for It Jes’ Happened: When Bill Traylor Started to Draw (Lee & Low), illustrated by R. Gregory Christie. Tate is also the illustrator of several picture books, including The Amazing Age of John Roy Lynch (Eerdmans), Whoosh! Lonnie Johnson’s Super-Soaking Stream of Inventions (Charlesbridge), and The Cart That Carried Martin (Charlesbridge). Like Eugen Sandow, Don Tate believes it is important for everyone—especially kids—to stay physically active. A former bodybuilder and gym rat, Don exercises every day. Each morning, he walks or runs. Several times a week, he lifts weights, practices yoga, or swims laps. He tries to eat healthy, too, in spite of his love of hamburgers, doughnuts, and Twizzlers. -

The Development of Muscular Christianity in Victorian Britain and Beyond

ISSN: 1522-5658 http://moses.creighton.edu/JRS/2005/2005-2.html The Development of Muscular Christianity in Victorian Britain and Beyond Nick J. Watson York St. John’s College, University of Leeds Stuart Weir Christians in Sport, UK Stephen Friend York St. John’s College, University of Leeds Introduction [1] The development of Muscular Christianity in the second half of the nineteenth century has had a sustained impact on how Anglo-American Christians view the relationship between sport, physical fitness, and religion. It has been argued that the birth of Muscular Christianity in Victorian Britain forged a strong “. link between Christianity and sport” that “. has never been broken” (Crepeau: 2). The emergence of neo-muscular Christian groups during the latter half of the twentieth century (Putney) and the promotion of sport in Catholic institutions, such as the University of Notre Dame, can be seen as a direct consequence of Victorian Muscular Christianity. Modern Evangelical Protestant organizations, such as Christians in Sport (CIS) in England and the Fellowship of Christian Athletes (FCA) in the U.S., have resurrected many of the basic theological principles used to promote sport and physical fitness in Victorian Britain. [2] The basic premise of Victorian Muscular Christianity was that participation in sport could contribute to the development of Christian morality, physical fitness, and “manly” character. The term was first adopted in the 1850s to portray the characteristics of Charles Kingsley (1819- 1875) and Thomas Hughes’ (1822-1896) novels. Both Kingsley and Hughes were keen sportsmen and advocates of the strenuous life. Fishing, hunting, and camping were Kingsley’s favorite pastimes, which he saw as a “counterbalance” to “. -

Yoga and Education (Grades K-12)

Yoga and Education (Grades K-12) Compiled by: Trisha Lamb Last Revised: April 27, 2006 © International Association of Yoga Therapists (IAYT) 2005 International Association of Yoga Therapists P.O. Box 2513 • Prescott • AZ 86302 • Phone: 928-541-0004 E-mail: [email protected] • URL: www.iayt.org The contents of this bibliography do not provide medical advice and should not be so interpreted. Before beginning any exercise program, see your physician for clearance. NOTE: For Yoga classes and other undergraduate and graduate Yoga-related studies in the university setting, s ee the “Undergraduate and Graduate Programs” bibliography. “The soul is the root. The mind is the trunk. The body constitutes the leaves. The leaves are no doubt important; they gather the sun’s rays for the entire tree. The trunk is equally important, perhaps more so. But if the root is not watered, neither will survive for long. “Education should start with the infant. Even the mother’s lullaby should be divine and soul elevating, infusing in the child fearlessness, joy, peace, selflessness and godliness. “Education is not the amassing of information and its purpose is not mere career hunting. It is a means of developing a fully integrated personality and enabling one to grow effectively into the likeness of the ideal that one has set before oneself. Education is a drawing out from within of the highest and best qualities inherent in the individual. It is training in the art of living.” —Swami Satyananda Saraswati Yoga, May 2001, p. 8 “Just getting into a school a few years ago was a big deal. -

1.3.1-YSH-456(Envi)

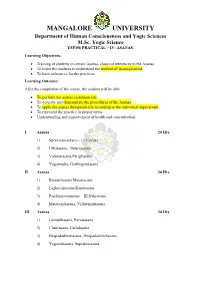

MANGALORE UNIVERSITY Department of Human Consciousness and Yogic Sciences M.Sc. Yogic Science YSP456 PRACTICAL – IV: ASANAS. Learning Objectives: • Training of students in certain Asanas, classical references to the Asanas. • To make the students to understand the method of Asana practice. • To have references for the practices. Learning Outcome: After the completion of the course, the student will be able – • To perform the asanas systematically. • To describe and demonstrate the procedures of the Asanas. • To apply the asanas therapeutically according to the individual requirement. • To represent the practice in proper terms. • Understanding and improvement of health and concentration. I Asanas 24 Hrs 1) Surya namaskara – 12 vinyasa 2) Utkatasana, Natarajasana 3) Vatayanasana,Parighasana 4) Yogamudra, Garbhapindasana II Asanas 24 Hrs 1) Kraunchasana,Mayurasana 2) Laghuvajrasana,Kapotasana 3) Paschimottanasana – III,Nakrasana 4) Matsyendrasana, Vishwamitrasana III Asanas 24 Hrs 1) Gomukhasana, Parvatasana 2) Chakrasana, Garudasana 3) Ekapadashirshasana, Dwipadashirshasana 4) Yoganidrasana, Suptakonasana REFERENCE BOOKS 1. Swami Digambarji(1997), Hathayoga pradeepika, SMYM Samiti, Kaivalyadhama, Lonavala, Pune - 410403 2. Swami Digambarji(1997), Gheranda Samhita, SMYMSamiti, Kaivalyadhama, Lonavala - 410403. 3. Swami Omananda Teertha, Patanjala Yoga Pradeepa, Gita Press, Gorakhpur-273005 4. JoisPattabhi (2010), Yoga mala – Part I, North Point Press, A Division ofFarrar, Straus and Giroux, 18 west 18the street, New York 10011. 5. B.K.S.Iyangar (1966), Light on Yoga .Harper Collins publication, 77- 85Fulham Palace road, London W6 8JB. 6. B.K.S.Iyangar(1999), Light on Pranayama,HarperCollins,New Delhi,-201307 7. Swami SatyanandaSaraswati(1997), Asana, Pranayama, Mudra, Bandha, Bihar School of Yoga, Munger-811201 8. Swami Geetananda, Bandhas & Mudras, Anandashrama, Pondicherry-605104 9. -

Modern Transnational Yoga: a History of Spiritual Commodification

Sacred Heart University DigitalCommons@SHU Master of Arts in Religious Studies (M.A.R.S. Theses) Philosophy, Theology and Religious Studies 8-2010 Modern Transnational Yoga: A History of Spiritual Commodification Jon A. Brammer Sacred Heart University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/rel_theses Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, and the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Brammer, Jon A., "Modern Transnational Yoga: A History of Spiritual Commodification" (2010). Master of Arts in Religious Studies (M.A.R.S. Theses). 29. https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/rel_theses/29 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy, Theology and Religious Studies at DigitalCommons@SHU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Arts in Religious Studies (M.A.R.S. Theses) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@SHU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Modern Transnational Yoga: A History of Spiritual Commodification Master's Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Religious Studies at Sacred Heart University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Religious Studies Jon A. Brammer August 2010 This thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Religious Studies Christel J. Manning, PhD., Professor of Religious Studies - ^ G l o Date Permission for reproducing this text, in whole or in part, for the purpose of individual scholarly consultation or other educational purposes is hereby granted by the author. This permission is not to be interpreted as granting publication rights for this work or otherwise placing it in the public domain. -

Luther Gulick: His Contributions to Springfield University, the YMCA

144 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Summer 2011 Luther Halsey Gulick II, c. 1900 (Courtesy of the Springfield College Archives) 145 Luther Gulick: His Contributions to Springfield College, the YMCA, and “Muscular Christianity” CLIFFORD PUTNEY Abstract: Based largely on hitherto unpublished archival sources, this article focuses on the early life and career of Luther Halsey Gulick II (1865-1918). Gulick was among America’s most influential educators in the Progressive Era. He is best known today for co- founding the Camp Fire Girls (CFG) with his wife Charlotte. But before his involvement with CFG he taught physical education for the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) at Springfield College, Massachusetts, in the 1890s. As a professor at Springfield, Gulick achieved a great deal, and this article examines his many accomplishments, including his invention of the YMCA Triangle (the organization’s official emblem) and his role in the invention of both basketball and volleyball. The article also analyzes Gulick’s unconventional childhood, when he travelled around the world with his parents. They were Congregational missionaries who fervently hoped Luther would embrace their brand of ascetic Christianity. He preferred a religion that was more corporeal, however. This led to him becoming a leader of the “muscular Christianity” movement. Muscular Christians espoused a combination of religion and sports, although, in the Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Vol. 39 (1 & 2), Summer 2011 © Institute for Massachusetts Studies, Westfield State University 146 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Summer 2011 end, Gulick ended up emphasizing sports over religion. Historian Clifford Putney has extensively researched the Gulick family and is the author of Missionaries in Hawai‘i: The Lives of Peter and Fanny Gulick, 1797-1883 (2010). -

Medicine, Sport and the Body: a Historical Perspective

Carter, Neil. "Sport as Medicine: Ideas of Health, Sport and Exercise." Medicine, Sport and the Body: A Historical Perspective. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2012. 13–35. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 26 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781849662062.ch-001>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 26 September 2021, 12:38 UTC. Copyright © Neil Carter 2012. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 1 Sport as Medicine Ideas of Health, Sport and Exercise Health Fanatic John Cooper Clarke (1978) … Shadow boxing – punch the wall One-a-side football... what’s the score... one-all Could have been a copper... too small Could have been a jockey... too tall Knees up, knees up... head the ball Nervous energy makes him tick He’s a health fanatic... he makes you sick This poem, written by the ‘punk poet’ John Cooper Clarke, the bard of Salford, encapsulated the reaction in some quarters to the health and fi tness boom, and its increasing visibility, in the post-war period. However, concern with personal health and wellbeing has not been a new phenomenon. Moreover, the use of sport and physical activity as a form of preventive medicine has been a cornerstone regarding ideas over the attainment of health. In 1929 the New Health Society proposed ten ‘Health Rules’ and, at number ten, after advice on topics such as diet, internal and external cleanliness and sunlight, was exercise in which the individual was encouraged to, ‘Take out-of-door exercise every day. -

![[Cejze.Ebook] Maxalding Pdf Free](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5801/cejze-ebook-maxalding-pdf-free-1055801.webp)

[Cejze.Ebook] Maxalding Pdf Free

ceJZE [Pdf free] Maxalding Online [ceJZE.ebook] Maxalding Pdf Free Monte Saldo ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1483811 in Books 2011-10-07Original language:English 9.00 x .25 x 6.00l, #File Name: 1466412070108 pages | File size: 33.Mb Monte Saldo : Maxalding before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Maxalding: 0 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Five StarsBy CustomerGood instruction in a basic isometric routine.0 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Five StarsBy JAMESGREAT BOOK4 of 6 people found the following review helpful. The Classic Maxalding!!!By Perry SandlinGreat reference on difficult art of Muscle Control. Buy this book it if you want to learn more about this highly effective "mind-body" workout approach. Find more similar titles, including other books on Muscle Control and a Free Catalog at www.StrongmanBooks.com Monte Saldo, together with Maxick, formed the Maxalding system of physical culture which was based upon muscle control and healthy living. Early on he became an apprentice to Eugen Sandow, and followed suit in strongman performances, one of his specialties being the ldquo;Tomb of Herculesrdquo;. In this book, Maxalding, yoursquo;ll find all the details on healthy living and then a total of 35 muscle control and bodyweight exercises, every single one of which has a picture displaying its correct technique. [ceJZE.ebook] Maxalding By Monte Saldo PDF [ceJZE.ebook] Maxalding By Monte Saldo Epub [ceJZE.ebook] Maxalding By Monte Saldo Ebook [ceJZE.ebook] Maxalding By Monte Saldo Rar [ceJZE.ebook] Maxalding By Monte Saldo Zip [ceJZE.ebook] Maxalding By Monte Saldo Read Online.