'Freaky:' an Exploration of the Development of Dominant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SLS 21RS-918 ORIGINAL 2021 Regular Session SENATE

SLS 21RS-918 ORIGINAL 2021 Regular Session SENATE RESOLUTION NO. 63 BY SENATOR BERNARD COMMENDATIONS. Commends Ronnie Coleman on being inducted into the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame. 1 A RESOLUTION 2 To commend Ronnie Coleman on being inducted into the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame. 3 WHEREAS, Ronnie Dean Coleman was born in Monroe, Louisiana, on May 13, 4 1964, and was a native of Bastrop, Louisiana; and 5 WHEREAS, he reached a high-level playing football during high school which 6 motivated him to lift weights and set out on his fitness journey; and 7 WHEREAS, Ronnie's performance as a football player led to a scholarship offer to 8 Grambling State University to study accounting and play football; and 9 WHEREAS, he played football as a middle linebacker with the GSU Tigers under 10 coach Eddie Robinson; and 11 WHEREAS, Ronnie Coleman graduated cum laude from Grambling State University 12 in 1984 with a bachelor's degree in accounting; and 13 WHEREAS, upon graduation he moved to Texas in search of work and eventually 14 became a police officer in Arlington, Texas, where he was an officer from 1989 to 2000 and 15 a reserve officer until 2003; and 16 WHEREAS, Ronnie joined the world famous Metroflex Gym, where he quickly 17 developed a bond with the owner, Brian Dobson; and 18 WHEREAS, Mr. Dobson ultimately gave Ronnie a lifetime free membership if he Page 1 of 3 SLS 21RS-918 ORIGINAL SR NO. 63 1 allowed Mr. Dobson to train him for competition; and 2 WHEREAS, Ronnie's hard work and determination lead to him winning the 1990 Mr. -

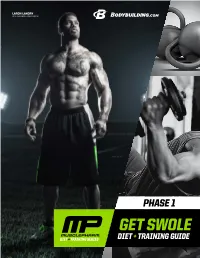

GET SWOLE Diet + Training Series DIET + TRAINING GUIDE GET SWOLE FOOD LIST + TRAINING GUIDE

Laron LandrY Pro FOOTBall suPERSTAR PHASE 1 GET SWOLE DIET + TRAINING SERIES DIET + TRAINING GUIDE GET SWOLE FOOD LIST + TRAINING GUIDE MEATS: VEGETABLES: • Chicken • Asparagus • Kale • Mackerel • Bamboo Shoots • Kohlrabi • Salmon • Bean Sprouts • Lettuces • Tuna • Beet Greens • Mushrooms • Lean Beef • Bok Choy Greens • Mustard Greens • Jerky • Broccoli • Parsley • Turkey • Cabbage • Radishes • Lunch Meat Ham • Cauliflower • Salad Greens • Lunch Meat Roast Beef • Celery • Sauerkraut • Eggs • Chards • Spinach String Beans • Chicory • Summer Squashes • Collard Greens • Turnip Greens • Cucumber • Watercress • Endive • Yellow Squash • Escarole • Zucchini Squash • Garlic CARBOHYDRATES: FATS: • Brown Rice • Avocado • Sweet Potato • Almonds • Quinoa • Cashews • Oatmeal • Olive Oil • Whole Wheat Bread • Whole Organic Butter • Ezekiel Bread • Walnuts • Whole Wheat Spaghetti • Kidney Beans • Yams • Black Beans • Barley • Brazil Nuts • Rye Bread • Pumpernickel Bread FRUITS: CONDIMENTS + SEASONINGS: • Apples • Spicy Mustard • Strawberries • Hot Sauce • Papaya • Crushed Red Pepper • Pears • Mrs. Dash Original Blend • Fresh Prunes • Mrs. Dash Fiesta Lime • Orange • Mrs. Dash Extra Spicy • Grapefruit • Mrs. Dash Tomato Basil Garlic • Kiwi • Mrs. Dash Lemon Pepper • Peaches TO SEE “PROPER FORM” EXERCISE VIDEOS,www.bodybuilding VISIT: MUSCLEPHARM.COM.com/getswole GET SWOLE PHASE 1: WEEKS 1–4 + TRAINING GUIDE EX. TIME: 7:00AM SUPPLEMENT: FOOD: Wake Up RE-CON®: 1/2 scoop • 3 whole eggs * Take with 8-12 oz. of water. • 1/4 cup oatmeal • 1 cup of fruit ARMOR-V™: 6 capsules * Take with 8-12 oz. of water. EX. TIME: 10:00AM SUPPLEMENT: FOOD: Mid-Morning COMBAT POWDER®: 2 scoops No Food * Take with 8-12 oz. of water & 2 oz. of heavy whipping cream. EX. TIME: 1:00PM SUPPLEMENT: FOOD: Lunch No Supplement Choose From Food List: Meat: 8 oz. -

University of California Riverside

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Choreographers and Yogis: Untwisting the Politics of Appropriation and Representation in U.S. Concert Dance A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Critical Dance Studies by Jennifer F Aubrecht September 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Jacqueline Shea Murphy, Chairperson Dr. Anthea Kraut Dr. Amanda Lucia Copyright by Jennifer F Aubrecht 2017 The Dissertation of Jennifer F Aubrecht is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I extend my gratitude to many people and organizations for their support throughout this process. First of all, my thanks to my committee: Jacqueline Shea Murphy, Anthea Kraut, and Amanda Lucia. Without your guidance and support, this work would never have matured. I am also deeply indebted to the faculty of the Dance Department at UC Riverside, including Linda Tomko, Priya Srinivasan, Jens Richard Giersdorf, Wendy Rogers, Imani Kai Johnson, visiting professor Ann Carlson, Joel Smith, José Reynoso, Taisha Paggett, and Luis Lara Malvacías. Their teaching and research modeled for me what it means to be a scholar and human of rigorous integrity and generosity. I am also grateful to the professors at my undergraduate institution, who opened my eyes to the exciting world of critical dance studies: Ananya Chatterjea, Diyah Larasati, Carl Flink, Toni Pierce-Sands, Maija Brown, and rest of U of MN dance department, thank you. I thank the faculty (especially Susan Manning, Janice Ross, and Rebekah Kowal) and participants in the 2015 Mellon Summer Seminar Dance Studies in/and the Humanities, who helped me begin to feel at home in our academic community. -

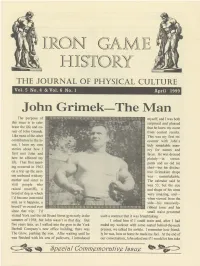

HOW STEVE REEVES TRAINED by John Grimek

IRON GAME HISTORY VOL.5No.4&VOL. 6 No. 1 IRON GAME HISTORY ATRON SUBSCRIBERS THE JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL CULTURE P Gordon Anderson Jack Lano VOL. 5 NO. 4 & VOL. 6 NO. 1 Joe Assirati James Lorimer SPECIAL DOUBL E I SSUE John Balik Walt Marcyan Vic Boff Dr. Spencer Maxcy TABLE OF CONTENTS Bill Brewer Don McEachren Bill Clark David Mills 1. John Grimek—The Man . Terry Todd Robert Conciatori Piedmont Design 6. lmmortalizing Grimek. .David Chapman Bruce Conner Terry Robinson 10. My Friend: John C. Grimek. Vic Boff Bob Delmontique Ulf Salvin 12. Our Memories . Pudgy & Les Stockton 4. I Meet The Champ . Siegmund Klein Michael Dennis Jim Sanders 17. The King is Dead . .Alton Eliason Mike D’Angelo Frederick Schutz 19. Life With John. Angela Grimek Lucio Doncel Harry Schwartz 21. Remembering Grimek . .Clarence Bass Dave Draper In Memory of Chuck 26. Ironclad. .Joe Roark 32. l Thought He Was lmmortal. Jim Murray Eifel Antiques Sipes 33. My Thoughts and Reflections. .Ken Rosa Salvatore Franchino Ed Stevens 36. My Visit to Desbonnet . .John Grimek Candy Gaudiani Pudgy & Les Stockton 38. Best of Them All . .Terry Robinson 39. The First Great Bodybuilder . Jim Lorimer Rob Gilbert Frank Stranahan 40. Tribute to a Titan . .Tom Minichiello Fairfax Hackley Al Thomas 42. Grapevine . Staff James Hammill Ted Thompson 48. How Steve Reeves Trained . .John Grimek 50. John Grimek: Master of the Dance. Al Thomas Odd E. Haugen Joe Weider 64. “The Man’s Just Too Strong for Words”. John Fair Norman Komich Harold Zinkin Zabo Koszewski Co-Editors . , . Jan & Terry Todd FELLOWSHIP SUBSCRIBERS Business Manager . -

Weightlifting

Weightlifting Ian South-Dickinson UDLS 7/ate/09 Overview 3 sports Powerlifting Olympic lifting Bodybuilding Training Powerlifting 3 attempts at 1 rep max Squat Bench Press Deadlift Tons of federations IPF, U.S.A.P.L, ADFPF, APF, APA, IPA, WPO Weight & Age classes Squat Squat Powerlifting Version Wide stance 350kg – 771 lbs http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EXj052Ht5pg @ 1:40 Bench Press Bench Press Powerlifting version Wide grip 606 lbs http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o3sED9fUvIg @ 1:10 Deadlift Deadlift Powerlifting version Sumo stance 363.7 lb http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NtMZeU12vXo Olympic 3 attempts at 1 rep max Clean & Jerk Snatch Summer Olympics event Women’s event added in 2000 Weight classes Clean & Jerk 258kg – 568lbs, gold medal 2008 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QQ3RBCemQ1I Snatch 76kg – 167 lbs http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B9RVr0HVkCg @ 1:10 Bodybuilding Sport? Judging Posing Muscle definition Symmetry Size Popularized by Ahnold in 70’s Steroid use in 70’s Steroids Synthetic hormones Testosterone Growth Hormone Genetic limits Illegal in 90’s Steroids & Weightlifting Bodybuilding Widely used Powerlifting Most drug test Olympics It’s the olympics Preparation Offseason Bulking, eating tons of food 12 weeks Extreme dieting 3 days Dehydration Low sodium, high potassium Tanning lotion Training Strength Training Olympic Training Bodybuilding Mix-n-match Training Effect Mostly depends on # reps per set, % of 1 rep max Hypertrophy – Increase in muscle size Myofibrillar – Muscle contractions Sarcoplasmic – Stores glycogen (simple -

About the Book: About the Author/Illustrator: About

A Standards-aligned Educator’s Guide for Grades 2-3 Strong As Sandow: How Eugen Sandow Became the Strongest Man on Earth LittleAbout Friedrich the Muller book: was a puny weakling who longed to be athletic and Age Range: 6-9 strong like the ancient Roman gladiators. He exercised and exercised. But he Grade Level: 2-3 was still puny. Hardcover: 40 pages As a young man, he found himself under the tutelage of a professional body Publisher: Charlesbridge builder. Friedrich worked and worked. He changed his name to Eugen ISBN: 978-1-58089-628-3 Sandow and he got bigger and stronger. Everyone wanted to become “as E-book ISBN: 978-1-60734-886-3 strong as Sandow.” AboutDon Tate is the author author/illustrator: and illustrator of Poet: The Remarkable Story of George Moses Horton (Peachtree), for which he received the Ezra Jack Keats New Writer Award. He received the Ezra Jack Keats New Writer Honor for It Jes’ Happened: When Bill Traylor Started to Draw (Lee & Low), illustrated by R. Gregory Christie. Tate is also the illustrator of several picture books, including The Amazing Age of John Roy Lynch (Eerdmans), Whoosh! Lonnie Johnson’s Super-Soaking Stream of Inventions (Charlesbridge), and The Cart That Carried Martin (Charlesbridge). Like Eugen Sandow, Don Tate believes it is important for everyone—especially kids—to stay physically active. A former bodybuilder and gym rat, Don exercises every day. Each morning, he walks or runs. Several times a week, he lifts weights, practices yoga, or swims laps. He tries to eat healthy, too, in spite of his love of hamburgers, doughnuts, and Twizzlers. -

Download High-Intensity Training the Mike Mentzer Way, Mike

High-Intensity Training the Mike Mentzer Way, Mike Mentzer, John R. Little, McGraw-Hill, 2002, 0071383301, 9780071383301, 288 pages. A PAPERBACK ORIGINALHigh-intensity bodybuilding advice from the first man to win a perfect score in the Mr. Universe competitionThis one-of-a-kind book profiles the high-intensity training (HIT) techniques pioneered by the late Mike Mentzer, the legendary bodybuilder, leading trainer, and renowned bodybuilding consultant. His highly effective, proven approach enables bodybuilders to get results--and win competitions--by doing shorter, less frequent workouts each week. Extremely time-efficient, HIT sessions require roughly 40 minutes per week of training--as compared with the lengthy workout sessions many bodybuilders would expect to put in daily.In addition to sharing Mentzer's workout and training techniques, featured here is fascinating biographical information and striking photos of the world-class bodybuilder--taken by noted professional bodybuilding photographers--that will inspire and instruct serious bodybuilders and weight lifters everywhere.. DOWNLOAD HERE http://bit.ly/1f8Qgh8 The World Gym Musclebuilding System , Joe Gold, Robert Kennedy, 1987, Health & Fitness, 179 pages. Briefly describes the background of World's Gym, tells how to get started in bodybuilding, and discusses diet, workout routines, and competitions. The Gold's Gym Training Encyclopedia , Peter Grymkowski, Edward Connors, Tim Kimber, Bill Reynolds, Sep 1, 1984, Health & Fitness, 272 pages. Demonstrates exercises and weight training routines for developing one's biceps, chest, shoulders, back, thighs, hips, triceps, abdomen, and forearms. Solid gold training the Gold's Gym way, Bill Reynolds, 1985, Health & Fitness, 216 pages. Discusses the basics of bodybuilding and provides guidance on the use of free weights and exercise equipment to develop the body. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 75-3121

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

A Briefly Annotated Bibliography of English Language Serial Publications in the Field of Physical Culture Jan Todd, Joe Roark and Terry Todd

MARCH 1991 IRON GAME HISTORY A Briefly Annotated bibliography of English Language Serial Publications in the Field of Physical Culture Jan Todd, Joe Roark and Terry Todd One of the major problems encountered when an attempt is made in January of 1869 and that we were unable to verify the actual starting to study the history of physical culture is that libraries have so seldom date of the magazine. saved (or subscribed to) even the major lifting, bodybuilding and “N.D.” means that the issue did not carry any sort of date. “N.M.” physical culture publications, let alone the minor ones. Because of this, means no month was listed. “N.Y.” means no year was listed. “N.V.” researchers have had to rely for the most part on private collections for means that no volume was listed. “N.N.” means that no issue number their source material, and this has limited the academic scholarship in was assigned. A question mark (?) beside a date means that we are the field. This problem was one of the major reasons behind the estimating when the magazine began, based on photos or other establishment of the Physical Culture Collection at the University of evidence. Texas in Austin. The designation “Current” means that, as of press time, the Over the last several months, we have made an attempt to magazine was still being published on a regular basis. You will also assemble a comprehensive listing or bibliography of the English- note the designation “LIC.” This stands for “Last in Collection.” This language magazines (and a few notable foreign language publications) simply means that the last copy of the magazine we have on hand here in the field of physical culture. -

Aobs Newsletter

AOBS NEWSLETTER The Association of Oldetime Barbell & Strongmen An International Iron Game Organization – Organized in 1982 (Vic Boff – Founder and President 1917-2002) P.O Box 680, Whitestone, NY 11357 (718) 661-3195 E-mail: [email protected] Web-Site: www.aobs.cc AUGUST 2009 and excellence. I thank them all very deeply for Our Historic 26th Annual Reunion - A Great agreeing to grace us with their presence. Beginning To the “Second” 25 Years! Then there was the veritable “Who’s Who” that came Quite honestly, after the record-breaking attendance and from everywhere to honor these great champions and to cavalcade of stars at our 25th reunion last year, we were join in a celebration of our values. Dr. Ken Rosa will worried about being able to have an appropriately have more to say about this in his report on our event, strong follow-up in our 26th year, for three reasons. but suffice it to say that without the support of the First, so many people made a special effort to attend in famous and lesser known achievers in attendance, the 2008, there was a concern that we might see a big drop event wouldn’t have been what it was. off in 2009. Second, there was the economy, undoubtedly the worst in decades, surely the worst since Then there was the staff of, and accommodations our organization began. Third, there were concern about offered by, the Newark Airport Marriott Hotel. We had the “swine flu” that was disproportionately impacting a very positive experience with this fine facility last the NY Metropolitan area. -

2008 OAH Annual Meeting • New York 1

Welcome ear colleagues in history, welcome to the one-hundred-fi rst annual meeting of the Organiza- tion of American Historians in New York. Last year we met in our founding site of Minneap- Dolis-St. Paul, before that in the national capital of Washington, DC. On the present occasion wew meet in the world’s media capital, but in a very special way: this is a bridge-and-tunnel aff air, not limitedli to just the island of Manhattan. Bridges and tunnels connect the island to the larger metropolitan region. For a long time, the peoplep in Manhattan looked down on people from New Jersey and the “outer boroughs”— Brooklyn, theth Bronx, Queens, and Staten Island—who came to the island via those bridges and tunnels. Bridge- and-tunnela people were supposed to lack the sophistication and style of Manhattan people. Bridge- and-tunnela people also did the work: hard work, essential work, beautifully creative work. You will sees this work in sessions and tours extending beyond midtown Manhattan. Be sure not to miss, for example,e “From Mambo to Hip-Hop: Th e South Bronx Latin Music Tour” and the bus tour to my own Photo by Steve Miller Steve by Photo cityc of Newark, New Jersey. Not that this meeting is bridge-and-tunnel only. Th anks to the excellent, hard working program committee, chaired by Debo- rah Gray White, and the local arrangements committee, chaired by Mark Naison and Irma Watkins-Owens, you can chose from an abundance of off erings in and on historic Manhattan: in Harlem, the Cooper Union, Chinatown, the Center for Jewish History, the Brooklyn Historical Society, the New-York Historical Society, the American Folk Art Museum, and many other sites of great interest. -

The Bodybuilding Truth

NELSON MONTANA THE BODYBUILDING TRUTH Dear friend and fellow athlete, Think you know about bodybuilding? Think again. If you really knew how to build the ultimate body in less than six months time, would you keep paying for more? More supplements? More personal training? More courses? More magazines? Would you keep spending your money on the deceptions, the product scams, the bogus supplements, and the false muscle building methods that the bodybuilding marketers propagate to line their pockets? The end result. Your bodybuilding progress is held back while the fat cats get rich. What if you knew the truth? What if someone were to blow the whistle on the con artists within the bodybuilding world and at the same time, share with you the secrets for packing on thick, dense muscle - fast! And burning off every last ounce of your bodyfat! Sounds unthinkable right? Well, the unthinkable has just happened. Every week I get at least one proposal from some self-appointed guru wanting us to publish his latest bodybuilding book. I read them, but never publish them, because basically, they're all worthless. However, the latest book by my friend Mr. Nelson Montana, titled The Bodybuilding Truth – Insider Secrets You're Not Supposed to Know, literally blew me away. And it blew away hundreds of ideas that I had accepted as truth for years about the sport of bodybuilding and exposed everything the bodybuilding marketers don't want you to know. Nelson Montana is an in your face kind of guy; he tells it like it is. A bodybuilding industry insider, Montana worked for Testosterone Magazine, but got fired because he refused to write an article touting ZMA, a fancy Zinc supplement, as the latest thing for muscle growth.