Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 75-3121

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Event Operations Internship AAU Junior Olympic Games

Event Operations Internship AAU Junior Olympic Games Operations Intern, AAU Junior Olympic Games The Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) is a multi-sport youth organization with millions of athletes, coaches, officials and volunteers who participate in 36 sports. The AAU Junior Olympic Games is the premier event of the AAU program and is the largest, multi-sports youth event in the country. Over a 2-week period, over 15,000 athletes participate in 25 sports. The 2008 AAU Junior Olympic Games will be held in Detroit, Michigan from July 23 to August 2. The Operations Intern will assist with a variety of projects with the coordination of the AAU Junior Olympic Games. Overview • Duration of Internship is May through mid-August • Intern will work at the AAU National Headquarters located in Lake Buena Vista, Florida near Walt Disney World Resort • Intern must be available to travel to Detroit, Michigan from July 23 to August 2. Travel, housing and per diem are provided during the event. • Internship provides a multitude of event management and operations experience Description • Assist in the daily planning, logistics and operations of the event • Handle requests for entry materials • Process entries for specific sports • Work with National Sport Chairs in conjunction with their specific sport needs and to develop operations plans • Assist with the travel and housing arrangements for all AAU officials and staff • Ordering of all plaques, ribbons, trophies and other awards for each sport • Provide support in the coordination of the Celebration of Athletes (Opening Ceremony) • Onsite logistics, trouble shooting, etc. during the event • Other duties as assigned. -

Bobbie Rosenfeld: the Olympian Who Could Do Everything by Anne Dublin

2005 GOLDEN OAK BOOK CLUB™ SELECTIONS Bobbie Rosenfeld: The Olympian Who Could Do Everything by Anne Dublin BOOK SUMMARY: Not so long ago, girls and women were discour- aged from playing games that were competitive and rough. Well into the 1950s, there was gen- der discrimination in sports. Girls were consid- ered too fragile and sensitive to play hard and to play well. But one woman astonished everyone. In fact, sportswriters and broadcasters in this country agree that Bobbie Rosenfeld may be Canada’s all-round greatest athlete of the twen- tieth century. Bobbie excelled at hockey, bas- ketball, softball, and track and field, and she became one of Canada’s first female Olympic medallists. Just as remarkable as her talent was her extraordinary sense of fair play. She greeted obstacles with courage, hard work, and a sense of humor, and she always put the team ahead of herself. In doing so, Bobbie set an example as a true athletic hero. AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY: Like Bobbie Rosenfeld, Anne Dublin came to Canada at a young age. She worked as an elementary school teacher for over 25 years, and taught in Kingston, Toronto, Winnipeg, and Nairobi. During her writing career, Anne has written short stories, articles, poetry, and a novel called Written on the Wind. Anne currently works as a teacher- librarian in Toronto. Ontario Library Association Reading Programs ©2002-2005. Bobbie Rosenfeld: The Olympian Who Could Do Everything by Anne Dublin Suggestions for Tutors/Instructors 6. Why did sports become more popular with women? Before starting to read the story, read (aloud) the outside 7. -

Rowing Australia Annual Report 2011-12

Rowing Australia Annual Report 2011–2012 Rowing Rowing Australia Office Address: 21 Alexandrina Drive, Yarralumla ACT 2600 Postal Address: PO Box 7147, Yarralumla ACT 2600 Phone: (02) 6214 7526 Rowing Australia Fax: (02) 6281 3910 Website: www.rowingaustralia.com.au Annual Report 2011–2012 Winning PartnershiP The Australian Sports Commission proudly supports Rowing Australia The Australian Sports Commission Rowing Australia is one of many is the Australian Government national sporting organisations agency that develops, supports that has formed a winning and invests in sport at all levels in partnership with the Australian Australia. Rowing Australia has Sports Commission to develop its worked closely with the Australian sport in Australia. Sports Commission to develop rowing from community participation to high-level performance. AUSTRALIAN SPORTS COMMISSION www.ausport.gov.au Rowing Australia Annual Report 2011– 2012 In appreciation Rowing Australia would like to thank the following partners and sponsors for the continued support they provide to rowing: Partners Australian Sports Commission Australian Olympic Committee State Associations and affiliated clubs Australian Institute of Sport National Elite Sports Council comprising State Institutes/Academies of Sport Corporate Sponsors 2XU Singapore Airlines Croker Oars Sykes Racing Corporate Supporters & Suppliers Australian Ambulance Service The JRT Partnership contentgroup Designer Paintworks/The Regatta Shop Giant Bikes ICONPHOTO Media Monitors Stage & Screen Travel Services VJ Ryan -

The Portrayal of Black Female Athletes in Children's Picturebooks

Strides Toward Equality: The Portrayal of Black Female Athletes in Children’s Picturebooks Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Rebekah May Bruce, M.A. Graduate Program in Education: Teaching and Learning The Ohio State University 2018 Dissertation Committee: Michelle Ann Abate, Advisor Patricia Enciso Ruth Lowery Alia Dietsch Copyright by Rebekah May Bruce 2018 Abstract This dissertation examines nine narrative non-fiction picturebooks about Black American female athletes. Contextualized within the history of children’s literature and American sport as inequitable institutions, this project highlights texts that provide insights into the past and present dominant cultural perceptions of Black female athletes. I begin by discussing an eighteen-month ethnographic study conducted with racially minoritized middle school girls where participants analyzed picturebooks about Black female athletes. This chapter recognizes Black girls as readers and intellectuals, as well as highlights how this project serves as an example of a white scholar conducting crossover scholarship. Throughout the remaining chapters, I rely on cultural studies, critical race theory, visual theory, Black feminist theory, and Marxist theory to provide critical textual and visual analysis of the focal picturebooks. Applying these methodologies, I analyze the authors and illustrators’ representations of gender, race, and class. Chapter Two discusses the ways in which the portrayals of track star Wilma Rudolph in Wilma Unlimited and The Quickest Kid in Clarksville demonstrate shifting cultural understandings of Black female athletes. Chapter Three argues that Nothing but Trouble and Playing to Win draw on stereotypes of Black Americans as “deviant” in order to construe tennis player Althea Gibson as a “wild child.” Chapter Four discusses the role of family support in the representations of Alice Coachman in Queen of the Track and Touch the Sky. -

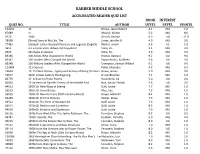

Barber Middle School Accelerated Reader Quiz List Book Interest Quiz No

BARBER MIDDLE SCHOOL ACCELERATED READER QUIZ LIST BOOK INTEREST QUIZ NO. TITLE AUTHOR LEVEL LEVEL POINTS 124151 13 Brown, Jason Robert 4.1 MG 5.0 87689 47 Mosley, Walter 5.3 MG 8.0 5976 1984 Orwell, George 8.9 UG 17.0 78958 (Short) Story of My Life, The Jones, Jennifer B. 4.0 MG 3.0 77482 ¡Béisbol! Latino Baseball Pioneers and Legends (English) Winter, Jonah 5.6 LG 1.0 9611 ¡Lo encontramos debajo del fregadero! Stine, R.L. 3.1 MG 2.0 9625 ¡No bajes al sótano! Stine, R.L. 3.9 MG 3.0 69346 100 Artists Who Changed the World Krystal, Barbara 9.7 UG 9.0 69347 100 Leaders Who Changed the World Paparchontis, Kathleen 9.8 UG 9.0 69348 100 Military Leaders Who Changed the World Crompton, Samuel Willard 9.1 UG 9.0 122464 121 Express Polak, Monique 4.2 MG 2.0 74604 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and Ecstasy of Being Thirteen Howe, James 5.0 MG 9.0 53617 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Grace/Bruchac 7.1 MG 1.0 66779 17: A Novel in Prose Poems Rosenberg, Liz 5.0 UG 4.0 80002 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems of the Middle East Nye, Naomi Shihab 5.8 UG 2.0 44511 1900-10: New Ways of Seeing Gaff, Jackie 7.7 MG 1.0 53513 1900-20: Linen & Lace Mee, Sue 7.3 MG 1.0 56505 1900-20: New Horizons (20th Century-Music) Hayes, Malcolm 8.4 MG 1.0 62439 1900-20: Print to Pictures Parker, Steve 7.3 MG 1.0 44512 1910-20: The Birth of Abstract Art Gaff, Jackie 7.6 MG 1.0 44513 1920-40: Realism and Surrealism Gaff, Jackie 8.3 MG 1.0 44514 1940-60: Emotion and Expression Gaff, Jackie 7.9 MG 1.0 36116 1940s from World War II to Jackie Robinson, The Feinstein, Stephen 8.3 -

Tracy Caulkins: She's No

USS NATIONALS BY BILL BELL PHOTOGRAPHY BY DAN HELMS TRACY CAULKINS: SHE'S NO. 1 Way back in the good oi' Indeed, there was a very good 39 national championships, set 31 days, before Tracy Caulkins swimmer. He was an American. An individual American records and Olympic champion. A world record one world record (the 200 IM at the was a tiny gleam in her holder. His name was Johnny Woodlands in August 1978). parents' eyes, before Weissmuller. At the C)'Connell Center Pool anybody had heard of Mark Tarzan. He could swing from the here in Gainesville, April 7-10, Spitz or Donna de Varona or vines with the best of 'em. But during the U.S. Short Course Debbie Meyer, back even before entering show biz he was a Nationals, she tied Weissmuller's 36 wins by splashing to the 200 back before the East German great swimmer. The greatest American swimmer (perhaps the title opening night (1:57.77, just off Wundermadchen or Ann greatest in all the world) of his era. her American record 1:57.02). The Curtis or smog in Los He won 36 national championships next evening Tarzan became just Angeles or Pac-Man over a seven-year span (1921-28) another name in the U.S. Swimming .... there was a swimmer. and rather than king of the jungle, record book as Caulkins won the Weissmuller should have been more 400 individual medley for No. 37, accurately known as king of the swept to No. 38 Friday night (200 swimming pool. IM) and climaxed her 14th Na- From 100 yards or meters through tionals by winning the 100 breast 500 yards or 400 meters he was Saturday evening. -

University of California Riverside

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Choreographers and Yogis: Untwisting the Politics of Appropriation and Representation in U.S. Concert Dance A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Critical Dance Studies by Jennifer F Aubrecht September 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Jacqueline Shea Murphy, Chairperson Dr. Anthea Kraut Dr. Amanda Lucia Copyright by Jennifer F Aubrecht 2017 The Dissertation of Jennifer F Aubrecht is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I extend my gratitude to many people and organizations for their support throughout this process. First of all, my thanks to my committee: Jacqueline Shea Murphy, Anthea Kraut, and Amanda Lucia. Without your guidance and support, this work would never have matured. I am also deeply indebted to the faculty of the Dance Department at UC Riverside, including Linda Tomko, Priya Srinivasan, Jens Richard Giersdorf, Wendy Rogers, Imani Kai Johnson, visiting professor Ann Carlson, Joel Smith, José Reynoso, Taisha Paggett, and Luis Lara Malvacías. Their teaching and research modeled for me what it means to be a scholar and human of rigorous integrity and generosity. I am also grateful to the professors at my undergraduate institution, who opened my eyes to the exciting world of critical dance studies: Ananya Chatterjea, Diyah Larasati, Carl Flink, Toni Pierce-Sands, Maija Brown, and rest of U of MN dance department, thank you. I thank the faculty (especially Susan Manning, Janice Ross, and Rebekah Kowal) and participants in the 2015 Mellon Summer Seminar Dance Studies in/and the Humanities, who helped me begin to feel at home in our academic community. -

2021 AAU Indoor Volleyball Age Divisions

1/4/2021 AAU - Volleyball 2021 AAU Indoor Volleyball Age Divisions The age determination date for AAU Indoor Volleyball in the 2020-2021 season has changed to July 1. For Beach Volleyball, the age determination date will remain as September 1. For full details on the Beach Volleyball age divisions, click here (https://aaubeach.org/AgeDivisions). Below are the 2021 age requirements for each indoor age division (exective Sept 1, 2020 - June 30, 2021). 10 & Must be born on or after July 1, 2010 --------------- Cannot turn 11 before July 1, Under 2021 11 & Must be born on or after July 1, 2009 --------------- Cannot turn 12 before July 1, Under 2021 12 & Must be born on or after July 1, 2008 --------------- Cannot turn 13 before July 1, Under 2021 13 & Must be born on or after July 1, 2007 --------------- Cannot turn 14 before July 1, Under 2021 14 & Must be born on or after July 1, 2006 --------------- Cannot turn 15 before July 1, Under 2021 15 & Must be born on or after July 1, 2005 --------------- Cannot turn 16 before July 1, Under 2021 16 & Must be born on or after July 1, 2004 --------------- Cannot turn 17 before July 1, Under 2021 https://aauvolleyball.org/Rules/AgeDivisions?pv=1 1/4 1/4/2021 AAU - Volleyball Below are the 2021 age requirements for each indoor age division (exective Sept 1, 2020 - June 30, 2021). 17 & Must be born on or after July 1, 2003 OR born on or after July 1, 2002 AND are in Under the 11th grade during the current academic year. -

'Freaky:' an Exploration of the Development of Dominant

From ‘Classical’ To ‘Freaky:’ an Exploration of the Development of Dominant, Organised, Male Bodybuilding Culture Dimitrios Liokaftos Department of Sociology, Goldsmiths, University of London Submitted for the Degree of PhD in Sociology February 2012 1 Declaration: The work presented in this thesis is my own. Dimitrios Liokaftos Signed, 2 Abstract Through a combination of historical and empirical research, the present thesis explores the development of dominant, organized bodybuilding culture across three periods: early (1880s-1930s), middle (1940s-1970s), and late (1980s-present). This periodization reflects the different paradigms in bodybuilding that the research identifies and examines at the level of body aesthetic, model of embodied practice, aesthetic of representation, formal spectacle, and prevalent meanings regarding the 'nature' of bodybuilding. Employing organized bodybuilding displays as the axis for the discussion, the project traces the gradual shift from an early bodybuilding model, represented in the ideal of the 'classical,' 'perfect' body, to a late-modern model celebrating the 'freaky,' 'monstrous' body. This development is shown to have entailed changes in notions of the 'good' body, moving from a 'restorative' model of 'all-around' development, health, and moderation whose horizon was a return to an unsurpassable standard of 'normality,' to a technologically-enhanced, performance- driven one where 'perfection' assumes the form of an open-ended project towards the 'impossible.' Central in this process is a shift in male identities, as the appearance of the body turns not only into a legitimate priority for bodybuilding practitioners but also into an instance of sport performance in bodybuilding competition. Equally central, and related to the above, is a shift from a model of amateur competition and non-instrumental practice to one of professional competition and extreme measures in search of the winning edge. -

Introduction

introduCtion A misty rain fell on the spectators gathered at Wembley Stadium in London, England, but the crowd was still strong at 60,000. It was the final day of track and field competition for the XIV Olympiad. Dusk was quickly approaching, but the women’s high jump competition was still underway. Two athletes remained, an American by the name of Alice Coachman and the British, hometown favorite, Dorothy Tyler. With an Olympic gold medal on the line, both athletes seemed content to remain all night, if necessary, as they continued to match each other at height after height. But then at 5 ´6½˝, neither one cleared the bar. The audience waited in the darkening drizzle while the judges conferred to determine who would be crowned the new Olympic champion. Finally, the judges ruled that one of the two athletes had indeed edged out the other through fewer missed attempts on previous heights. Alice Coachman had just become the first African American woman to win an Olympic gold 1 medal. Her leap of 5 ´6 ⁄8˝ on that August evening in 1948 set new Olympic and American records for the women’s high jump. The win cul - minated a virtually unparalleled ten-year career in which she amassed an athletic record of thirty-six track and field national championships— twenty-six individual and ten team titles. From 1939, when she first won the national championship for the high jump at the age of sixteen, she never surrendered it; a new champion came only after her retirement at the conclusion of the Olympics. -

Code De Conduite Pour Le Water Polo

HistoFINA SWIMMING MEDALLISTS AND STATISTICS AT OLYMPIC GAMES Last updated in November, 2016 (After the Rio 2016 Olympic Games) Fédération Internationale de Natation Ch. De Bellevue 24a/24b – 1005 Lausanne – Switzerland TEL: (41-21) 310 47 10 – FAX: (41-21) 312 66 10 – E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.fina.org Copyright FINA, Lausanne 2013 In memory of Jean-Louis Meuret CONTENTS OLYMPIC GAMES Swimming – 1896-2012 Introduction 3 Olympic Games dates, sites, number of victories by National Federations (NF) and on the podiums 4 1896 – 2016 – From Athens to Rio 6 Olympic Gold Medals & Olympic Champions by Country 21 MEN’S EVENTS – Podiums and statistics 22 WOMEN’S EVENTS – Podiums and statistics 82 FINA Members and Country Codes 136 2 Introduction In the following study you will find the statistics of the swimming events at the Olympic Games held since 1896 (under the umbrella of FINA since 1912) as well as the podiums and number of medals obtained by National Federation. You will also find the standings of the first three places in all events for men and women at the Olympic Games followed by several classifications which are listed either by the number of titles or medals by swimmer or National Federation. It should be noted that these standings only have an historical aim but no sport signification because the comparison between the achievements of swimmers of different generations is always unfair for several reasons: 1. The period of time. The Olympic Games were not organised in 1916, 1940 and 1944 2. The evolution of the programme. -

Stirs Marimrough Oaeandmus

iNET PRESS RUN “I THE WEATHER. AVERAGE DAILY CIRCULATION Cloudy tonight. Probably show OP THE EVENING HERALD ers Tuesday. Little change in tem for the month of May, 1920. perature. 4,915 anthpBter lEufUing feraUi ____________________________ ______________________________________________ „ ----------------------------------------------- ------ --------------------- Cotaa- (TWELVE PAGES) PRICE THREE CENTS MANCHESTER, CONN., MONDAY, JUNE VOL. XLIV., NO. 223. Classified Adrertising on Page 8 Will Fly to Paris CHARCOAL PIT I Best Speller in U. S. OAEAN DM U S Sen. Warren, Dean of Congress, I TOBACCO BILL EXPEa SUNKEN RESUME PAPER Begins Eighty-third Year Today OF NATION NOW $.51 TO COME TO ‘TRAGEDY’ STIRS I Washington, June 21. — Thcj.common sense, a willingness to Ira- dean of congress in age and ser prove himself every day and a de IS SURFACETODAY MARIMROUGH M A W SOON vice, Sen. Francis E. Warren, Re sire to serve his nation first, his <» ■■ publican of W'yoming, today enter constitutents second, to the best of ed his eighty-third year, cne of the his ability.” oldest men ever to serve in the na While in the Senate, W'arren has More Money Goes to Lady This Evening or Tomorrow American Writing Paper tional legislature. seen eight men elected to the presi Little Town “ Agog” Over With a record of ne.arly 34 y.'irs dency. They were Presidents Harri in tue Senate, W.a;re i lias succeed son, Cleveland, McKinley, Roose Nicotine Than Ever Was Morning Set for Final Most Excitement in Years Company Reorganizes; ed to the post formerly held by velt, Taft, Wilson, Harding and •'Uncle Joe” Cannon.