Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Portrayal of Black Female Athletes in Children's Picturebooks

Strides Toward Equality: The Portrayal of Black Female Athletes in Children’s Picturebooks Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Rebekah May Bruce, M.A. Graduate Program in Education: Teaching and Learning The Ohio State University 2018 Dissertation Committee: Michelle Ann Abate, Advisor Patricia Enciso Ruth Lowery Alia Dietsch Copyright by Rebekah May Bruce 2018 Abstract This dissertation examines nine narrative non-fiction picturebooks about Black American female athletes. Contextualized within the history of children’s literature and American sport as inequitable institutions, this project highlights texts that provide insights into the past and present dominant cultural perceptions of Black female athletes. I begin by discussing an eighteen-month ethnographic study conducted with racially minoritized middle school girls where participants analyzed picturebooks about Black female athletes. This chapter recognizes Black girls as readers and intellectuals, as well as highlights how this project serves as an example of a white scholar conducting crossover scholarship. Throughout the remaining chapters, I rely on cultural studies, critical race theory, visual theory, Black feminist theory, and Marxist theory to provide critical textual and visual analysis of the focal picturebooks. Applying these methodologies, I analyze the authors and illustrators’ representations of gender, race, and class. Chapter Two discusses the ways in which the portrayals of track star Wilma Rudolph in Wilma Unlimited and The Quickest Kid in Clarksville demonstrate shifting cultural understandings of Black female athletes. Chapter Three argues that Nothing but Trouble and Playing to Win draw on stereotypes of Black Americans as “deviant” in order to construe tennis player Althea Gibson as a “wild child.” Chapter Four discusses the role of family support in the representations of Alice Coachman in Queen of the Track and Touch the Sky. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 75-3121

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

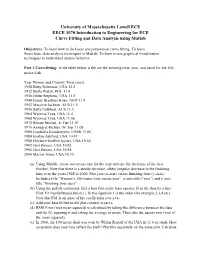

EECE 1070 Curve Fitting and Data Analysis

University of Massachusetts Lowell ECE EECE 1070 Introduction to Engineering for ECE Curve Fitting and Data Analysis using Matlab Objectives: To learn how to do linear and polynomial curve fitting. To learn Some basic data analysis techniques in Matlab; To learn to use graphical visualization techniques to understand system behavior. Part 1 Curvefitting: In the table below is the are the winning time, year, and name for the 100- meter dash. Year Winner and Country Time (secs) 1928 Betty Robinson, USA 12.2 1932 Stella Walsh, POL 11.9 1936 Helen Stephens, USA 11.5 1948 Fanny Blankers-Koen, NED 11.9 1952 Marjorie Jackson, AUS 11.5 1956 Betty Cuthbert, AUS 11.5 1964 Wyomia Tyus, USA 11.4 1968 Wyomia Tyus, USA 11.08 1972 Renate Stecher, E. Ger 11.07 1976 Annegret Richter, W. Ger 11.08 1980 Lyudmila Kondratyeva, USSR 11.06 1984 Evelyn Ashford, USA 10.97 1988 Florence Griffith Joyner, USA 10.54 1992 Gail Devers, USA 10.82 1996 Gail Devers, USA 10.94 2000 Marion Jones, USA 10.75 (a) Using Matlab, create two arrays one for the year and one for the times of the best finisher. Note that there is a steady decrease, albeit irregular decrease in the finishing time over the years 1928 to 2000. Plot year (x-axis) versus finishing time (y-axis). Include a title “Women’s 100-meter time versus year”, x-axis title (“year”) and y’axis title “finishing time (sec)” (b) Using the polyfit command, find a best first order least squares fit to the data by a line: Hint: Fit1=polyfit(year,finish,1). -

Tennessee State University Olympic Tradition Sharon Smith Tennessee State University, [email protected]

Tennessee State University Digital Scholarship @ Tennessee State University Library Faculty and Staff ubP lications and TSU Libraries and Media Centers Presentations 1-1-2007 Tennessee State University Olympic Tradition Sharon Smith Tennessee State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalscholarship.tnstate.edu/lib Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Sharon, "Tennessee State University Olympic Tradition" (2007). Library Faculty and Staff Publications and Presentations. Paper 2. http://digitalscholarship.tnstate.edu/lib/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the TSU Libraries and Media Centers at Digital Scholarship @ Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Library Faculty and Staff ubP lications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship @ Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TennesseeTennessee StateState UniversityUniversity SpecialSpecial CollectionsCollections PresentsPresents TennesseeTennessee StateState UniversityUniversity OlympicOlympic TraditionTradition 1 IntroductionIntroduction ¾¾SpecialSpecial emphasisemphasis onon thethe TSUTSU OlympicOlympic traditiontradition ¾¾AchievementsAchievements ofof TSUTSU athletesathletes 2 CoachCoach EdwardEdward S.S. TempleTemple TempleTemple servedserved asas HeadHead WomenWomen’’ss TrackTrack CoachCoach forfor fortyforty--fourfour yearsyears atat TSU,TSU, Nashville,Nashville, TennesseeTennessee -

SOT - Randalls Island - July 3-4/ OT Los Angeles - September 12-13

1964 MEN Trials were held in Los Angeles on September 12/13, some 5 weeks before the Games, after semi-final Trials were held at Travers Island in early July with attendances of 14,000 and 17,000 on the two days. To give the full picture, both competitions are analyzed here. SOT - Randalls Island - July 3-4/ OT Los Angeles - September 12-13 OT - 100 Meters - September 12, 16.15 Hr 1. 5. Bob Hayes (Florida A&M) 10.1 2. 2. Trenton Jackson (Illinois) 10.2 3. 7. Mel Pender (US-A) 10.3 4. 8. Gerry Ashworth (Striders) [10.4 –O] 10.3e 5. 6. Darel Newman (Fresno State) [10.4 – O] 10.3e 6. 1. Charlie Greene (Nebraska) 10.4 7. 3. Richard Stebbins (Grambling) 10.4e 8. 4. Bernie Rivers (New Mexico) 10.4e Bob Hayes had emerged in 1962, after a 9.3y/20.1y double at the '61 NAIA, and inside 3 seasons had stamped himself as the best 100 man of all-time. However, in the AAU he injured himself as he crossed the line, and he was in the OT only because of a special dispensation. In the OT race Newman started well but soon faded and Hayes, Jackson and Pender edged away from the field at 30m, with Hayes' power soon drawing clear of the others. He crossed the line 5ft ahead, still going away, and the margin of 0.1 clearly flattered Jackson. A time of 10.3 would have been a fairer indication for both Jackson and Ashworth rather than the official version of 10.4, while Stebbins and Rivers (neither officially timed) are listed at 10.4e from videotape. -

Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 Saturday 02 November 2013 11:00

Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 Saturday 02 November 2013 11:00 International Autograph Auctions (IAA) Office address Foxhall Business Centre Foxhall Road NG7 6LH International Autograph Auctions (IAA) (Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 ) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 tennis players of the 1970s TENNIS: An excellent collection including each Wimbledon Men's of 31 signed postcard Singles Champion of the decade. photographs by various tennis VG to EX All of the signatures players of the 1970s including were obtained in person by the Billie Jean King (Wimbledon vendor's brother who regularly Champion 1966, 1967, 1968, attended the Wimbledon 1972, 1973 & 1975), Ann Jones Championships during the 1970s. (Wimbledon Champion 1969), Estimate: £200.00 - £300.00 Evonne Goolagong (Wimbledon Champion 1971 & 1980), Chris Evert (Wimbledon Champion Lot: 2 1974, 1976 & 1981), Virginia TILDEN WILLIAM: (1893-1953) Wade (Wimbledon Champion American Tennis Player, 1977), John Newcombe Wimbledon Champion 1920, (Wimbledon Champion 1967, 1921 & 1930. A.L.S., Bill, one 1970 & 1971), Stan Smith page, slim 4to, Memphis, (Wimbledon Champion 1972), Tennessee, n.d. (11th June Jan Kodes (Wimbledon 1948?), to his protégé Arthur Champion 1973), Jimmy Connors Anderson ('Dearest Stinky'), on (Wimbledon Champion 1974 & the attractive printed stationery of 1982), Arthur Ashe (Wimbledon the Hotel Peabody. Tilden sends Champion 1975), Bjorn Borg his friend a cheque (no longer (Wimbledon Champion 1976, present) 'to cover your 1977, 1978, 1979 & 1980), reservation & ticket to Boston Francoise Durr (Wimbledon from Chicago' and provides Finalist 1965, 1968, 1970, 1972, details of the hotel and where to 1973 & 1975), Olga Morozova meet in Boston, concluding (Wimbledon Finalist 1974), 'Crazy to see you'. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E214 HON

E214 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks February 10, 2005 Emergency Manager before he began his ten- Champ was. His wife, children, and grand- their invaluable contributions to athletics, the ure as Commissioner. children are a great testament to who he was United States, and the entire world. Commissioner Fischler has commanded as a person. My prayers are with his family, f major incidents, including hurricanes and friends, and community today, as we honor his coastal storms that destroyed 104 homes in life. INTRODUCTION OF THE SANITY OF LIFE ACT AND THE TAXPAYER 48 hours, the 1995 Wildfires, the 1996 TWA f incident, and the county’s response in 2001 to FREEDOM OF CONSCIENCE ACT the World Trade Center in support of our HONORING THE 2004 AFRICAN neighbors in New York City. His skill as a AMERICAN ETHNIC SPORTS HON. RON PAUL leader, manager and emergency services ex- HALL OF FAME INDUCTEES OF TEXAS pert invariably saved lives, property and hard- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ship for the people of our community in each HON. BARBARA LEE Thursday, February 10, 2005 of these instances. Most importantly, he en- OF CALIFORNIA sured professional, timely, organized response IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Mr. PAUL. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to intro- duce two bills relating to abortion. These bills in the event of each challenging disaster. Thursday, February 10, 2005 Commissioner Fischler is also a vice-presi- stop the federal government from promoting dent of the NYS Emergency Management As- Ms. LEE. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to honor abortion. My bills accomplish this goal by pro- sociation, a member of the International Asso- the inductions of twelve former black Olym- hibiting federal funds from being used for pop- ciation of Fire Chiefs Terrorism/Homeland Se- pians into the African American Ethnic Sports ulation control or ‘‘family planning’’ through ex- curity Committee and has spoken extensively Hall of Fame on July 8, 2004 in Sacramento, ercising Congress’s constitutional power to re- throughout the country. -

Black History in the Olympics

Black history in the olympics By Manny & Soleil TIME LINE 1912: First black 1960: First female 2018: First black 1908: First black Canadian to 1948: First female black Olympian to female speed Olympian: John compete in the black Olympian: win multiple gold skater: Maame Baxter Taylor Jr Olympic games: Alice Coachman medals: Wilma Biney John Armstrong Rudolph 1908: First Black Olympian: John Baxter Taylor Jr • https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Taylor_(athlete) What sport was he in? Track and field. What country was he representing? The United States. Where is he originally from? He was from London. How old was he when he won his first medal? He was 26 when he won his first medal. 1912: First Black Canadian to Compete in the Olympic games: John Armstrong Howard • https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Howard_(athlete) What sport did he compete in? He competed in track. What part of Canada was he from? He was from Manitoba. What are some of the challenges he faced as a black athlete in 1912 going into the Olympics. He had to stay in a different hotel and he couldn’t eat in the same areas as the other athletes. What was he doing before he became an athlete? He played baseball. 1948: First Black Female Olympian: Alice Coachman • https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alice_Coachman What sport did she compete in? She competed in the high jump. What country did she represent? She represented the United States. How did she train since she had trouble accessing the normal facilities that other athletes used? She would run barefoot in fields near her home. -

Detailed List of Performances in the Six Selected Events

Detailed list of performances in the six selected events 100 metres women 100 metres men 400 metres women 400 metres men Result Result Result Result Year Athlete Country Year Athlete Country Year Athlete Country Year Athlete Country (sec) (sec) (sec) (sec) 1928 Elizabeth Robinson USA 12.2 1896 Tom Burke USA 12.0 1964 Betty Cuthbert AUS 52.0 1896 Tom Burke USA 54.2 Stanislawa 1900 Frank Jarvis USA 11.0 1968 Colette Besson FRA 52.0 1900 Maxey Long USA 49.4 1932 POL 11.9 Walasiewicz 1904 Archie Hahn USA 11.0 1972 Monika Zehrt GDR 51.08 1904 Harry Hillman USA 49.2 1936 Helen Stephens USA 11.5 1906 Archie Hahn USA 11.2 1976 Irena Szewinska POL 49.29 1908 Wyndham Halswelle GBR 50.0 Fanny Blankers- 1908 Reggie Walker SAF 10.8 1980 Marita Koch GDR 48.88 1912 Charles Reidpath USA 48.2 1948 NED 11.9 Koen 1912 Ralph Craig USA 10.8 Valerie Brisco- 1920 Bevil Rudd SAF 49.6 1984 USA 48.83 1952 Marjorie Jackson AUS 11.5 Hooks 1920 Charles Paddock USA 10.8 1924 Eric Liddell GBR 47.6 1956 Betty Cuthbert AUS 11.5 1988 Olga Bryzgina URS 48.65 1924 Harold Abrahams GBR 10.6 1928 Raymond Barbuti USA 47.8 1960 Wilma Rudolph USA 11.0 1992 Marie-José Pérec FRA 48.83 1928 Percy Williams CAN 10.8 1932 Bill Carr USA 46.2 1964 Wyomia Tyus USA 11.4 1996 Marie-José Pérec FRA 48.25 1932 Eddie Tolan USA 10.3 1936 Archie Williams USA 46.5 1968 Wyomia Tyus USA 11.0 2000 Cathy Freeman AUS 49.11 1936 Jesse Owens USA 10.3 1948 Arthur Wint JAM 46.2 1972 Renate Stecher GDR 11.07 Tonique Williams- 1948 Harrison Dillard USA 10.3 1952 George Rhoden JAM 45.9 2004 BAH 49.41 1976 -

Protest at the Pyramid: the 1968 Mexico City Olympics and the Politicization of the Olympic Games Kevin B

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2003 Protest at the Pyramid: The 1968 Mexico City Olympics and the Politicization of the Olympic Games Kevin B. Witherspoon Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES PROTEST AT THE PYRAMID: THE 1968 MEXICO CITY OLYMPICS AND THE POLITICIZATION OF THE OLYMPIC GAMES By Kevin B. Witherspoon A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2003 The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Kevin B. Witherspoon defended on Oct. 6, 2003. _________________________ James P. Jones Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________ Patrick O’Sullivan Outside Committee Member _________________________ Joe M. Richardson Committee Member _________________________ Valerie J. Conner Committee Member _________________________ Robinson Herrera Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project could not have been completed without the help of many individuals. Thanks, first, to Jim Jones, who oversaw this project, and whose interest and enthusiasm kept me to task. Also to the other members of the dissertation committee, V.J. Conner, Robinson Herrera, Patrick O’Sullivan, and Joe Richardson, for their time and patience, constructive criticism and suggestions for revision. Thanks as well to Bill Baker, a mentor and friend at the University of Maine, whose example as a sports historian I can only hope to imitate. Thanks to those who offered interviews, without which this project would have been a miserable failure: Juan Martinez, Manuel Billa, Pedro Aguilar Cabrera, Carlos Hernandez Schafler, Florenzio and Magda Acosta, Anatoly Isaenko, Ray Hegstrom, and Dr. -

The Olympic 100M Sprint

Exploring the winning data: the Olympic 100 m sprint Performances in athletic events have steadily improved since the Olympics first started in 1896. Chemists have contributed to these improvements in a number of ways. For example, the design of improved materials for clothing and equipment; devising and monitoring the best methods for training for particular sports and gaining a better understanding of how energy is released from our food so ensure that athletes get the best diet. Figure 1 Image of a gold medallist in the Olympic 100 m sprint. Year Winner (Men) Time (s) Winner (Women) Time (s) 1896 Thomas Burke (USA) 12.0 1900 Francis Jarvis (USA) 11.0 1904 Archie Hahn (USA) 11.0 1906 Archie Hahn (USA) 11.2 1908 Reginald Walker (S Africa) 10.8 1912 Ralph Craig (USA) 10.8 1920 Charles Paddock (USA) 10.8 1924 Harold Abrahams (GB) 10.6 1928 Percy Williams (Canada) 10.8 Elizabeth Robinson (USA) 12.2 1932 Eddie Tolan (USA) 10.38 Stanislawa Walasiewick (POL) 11.9 1936 Jessie Owens (USA) 10.30 Helen Stephens (USA) 11.5 1948 Harrison Dillard (USA) 10.30 Fanny Blankers-Koen (NED) 11.9 1952 Lindy Remigino (USA) 10.78 Majorie Jackson (USA) 11.5 1956 Bobby Morrow (USA) 10.62 Betty Cuthbert (AUS) 11.4 1960 Armin Hary (FRG) 10.32 Wilma Rudolph (USA) 11.3 1964 Robert Hayes (USA) 10.06 Wyomia Tyus (USA) 11.2 1968 James Hines (USA) 9.95 Wyomia Tyus (USA) 11.08 1972 Valeriy Borzov (USSR) 10.14 Renate Stecher (GDR) 11.07 1976 Hasely Crawford (Trinidad) 10.06 Anneqret Richter (FRG) 11.01 1980 Allan Wells (GB) 10.25 Lyudmila Kondratyeva (USA) 11.06 1984 Carl Lewis (USA) 9.99 Evelyn Ashford (USA) 10.97 1988 Carl Lewis (USA) 9.92 Florence Griffith-Joyner (USA) 10.62 1992 Linford Christie (GB) 9.96 Gail Devers (USA) 10.82 1996 Donovan Bailey (Canada) 9.84 Gail Devers (USA) 10.94 2000 Maurice Green (USA) 9.87 Eksterine Thanou (GRE) 11.12 2004 Justin Gatlin (USA) 9.85 Yuliya Nesterenko (BLR) 10.93 2008 Usain Bolt (Jam) 9.69 Shelly-Ann Fraser (Jam) 10.78 2012 Usain Bolt (Jam) 9.63 Shelly-Ann Fraser (Jam) 10.75 Exploring the wining data: 100 m sprint| 11-16 Questions 1. -

The Tennessee State Tigerbelles

4 The Tennessee State Tigerbelles Cold Warriors of the Track Carroll Van West In the lore of Tennessee sports history, few names are more evocative and lionized than the Tennessee State Tigerbelles, a group of women sprinters who dominated track and field events in the nation and world from the mid-1950s to mid-1980s.1 Scholarly interest in the impact of the Tigerbelles has multiplied in the twenty-first century, with dissertations and books addressing how these women track and field stars shaped mid-twentieth-century images of African American women, women involved in sports in general, and issues of civil rights and international affairs.2 The story of the Tigerbelles and their significance to American sport and cul- ture must center on the great talent and dedication to excellence of these young women. But as media coverage of their athletic exploits intensified from the early 1950s to the 1960s, the Tigerbelles were swept up in American preoccupation with the role of women in contemporary sport, the impact of race in American sport, and the role that amateur athletes could play as pawns in the propaganda postur- ings of the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Track and field at Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial State College (renamed in 1968 as Tennessee State University) began in the aftermath of Jessie Owens’s success at the 1936 Olympics. The college’s first women’s track team formed in 1943 under the direction of Jessie Abbott, succeeded by Lula Bartley in 1945. Abbott brought with him a commitment to excellence gained at Tuskegee Institute, home to the first nationally dominant African American track and field program.