Tennessee State University and US Olympic Women's Track and Field

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clayborn Temple AME Church

«Sí- ’.I-.--”;; NEWS WHILE IT IS NEI FIRST IK YOUR ME WORLD ' i; VOLUME 23, NUMBER 100 MEMPHIS, TENNESSEE, TUESDAY, JUNE 14, 1955 « t With Interracial Committee (Special to Memphis World) NASHVILLE—(SNS) -N ashville and Davidson County school board officials moved to tackle the public school desegregation problem when last weekend both city and county school boards ordered studies begun on the school desegregation issue. t stand atom« dfee.Jwd The county board took the strong year. er action, directing the superinten The boards are said to be con dent and board chairman to work sidering three approaches to the out plans with an Interracial com school desegregation problem The mittee to be selected by the chair three approaches include (1) the man. "voluntary” approach wherein Ne The city board referred a copy gro parents would say whether of the Supreme Court ruling to one they want their children to register « IUaW of its standing committees along lit former "white" schools or re with a . request from Robert Remit main In Negro schools; (2) the FOUR-YEAR SCHOLARSHIP AWARDEES - Dr. and saluataforlan, respectively, of this year's ter, a white associate professor of abolition of all school zones which William L. Crump (left) Director of Tennessee Haynes High School graduating class. Both mathematics at Fisk, that his two would make it possible for students State University's Bureau,of Public Relations an’d young ladies were presented four-year academ children be admitted to "Negro" to register at the school of their schools. choice or i3> "gradual" integration Clinton Derricks (right) principal of the Haynes ic scholarships to Tennessee State during the A similar request by Mr. -

2020 Olympic Games Statistics

2020 Olympic Games Statistics - Women’s 400m by K Ken Nakamura The records to look for in Tokyo: 1) Can Miller-Uibo become only the second (after Perec) 400m sprinter to win the Olympic twice. Summary Page: All time Performance List at the Olympic Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 48.25 Marie -Jose Perec FRA 1 Atlanta 1996 2 2 48.63 Cathy Freeman AUS 2 Atla nta 1996 3 3 48.65 Olga Bryzgina URS 1 Seoul 1988 4 4 48.83 Valerie Brisco -Hooks USA 1 Los Angeles 1984 4 48 .83 Marie Jose -Perec 1 Barcelona 1992 6 5 48.88 Marita Koch GDR 1 Moskva 1980 7 6 49.05 Chandra Cheeseborough USA 2 Los Angeles 1984 Slowest winning time since 1976: 49.62 by Christine Ohuruogu (GBR) in 2008 Margin of Victory Difference Winning time Name Nat Venue Year Max 1.23 49.28 Irena Szewinska POL Montreal 1976 Min 0.07 49.62 Christine Ohuruogu GBR Beijing 20 08 49.44 Shaunae Miller BAH Rio de Janeiro 2016 Fastest time in each round Round Time Name Nat Venue Year Final 48.25 Marie -Jose Perec FRA Atlanta 1996 Semi-final 49.11 Olga Nazarova URS Seoul 1988 First round 50.11 Sanya Richards USA Athinai 2004 Fastest non-qualifier for the final Time Position Name Nat Venue Year 49.91 5sf1 Jillian Richardson CAN Seoul 1988 Best Marks for Places in the Olympics Pos Time Name Nat Venue Year 1 48.25 Marie -Jose Perec FRA Atlanta 1996 2 48.63 Cathy Freeman AUS Atlanta 1996 3 49.10 Falilat Ogunkoya NGR Atlanta 1996 Last nine Olympics: Year Gold Nat Time Silver Nat Time Bronze Nat Time 2016 Shaunae Miller BAH 49.44 Allyson Felix USA 49.51 Shericka Jackson -

Leveled Reader - Wilma Rudolph Running to Win - BLUE.Pdf

52527_CVR.indd Page A-B 6/11/09 11:18:32 PM user-044 /Volumes/104/SF00327/work%0/indd%0/SF_RE_TX:NL_L... Suggested levels for Guided Reading, DRA,™ Lexile,® and Reading Recovery™ are provided in the Pearson Scott Foresman Leveling Guide. byby MeishMeish GoldishGoldish Comprehension Genre Text Features Skills and Strategy Expository • Generalize • Table of Contents nonfi ction • Author’s Purpose • Captions • Predict and Set • Glossary Purpose Scott Foresman Reading Street 5.4.2 ISBN-13: 978-0-328-52527-0 ISBN-10: 0-328-52527-8 90000 9 780328 525270 LeYWXkbWho :WbcWj_Wd \h_bbo fhec[dWZ_d] ifhW_d[Z XoC[_i^=ebZ_i^Xo C[_i^ =ebZ_i^ ikXij_jkj[ MehZYekdj0(")+, Note: The total word count includes words in the running text and headings only. Numerals and words in chapter titles, captions, labels, diagrams, charts, graphs, sidebars, and extra features are not included. (MFOWJFX *MMJOPJTt#PTUPO .BTTBDIVTFUUTt$IBOEMFS "SJ[POBt 6QQFS4BEEMF3JWFS /FX+FSTFZ Chapter 1 A Difficult Childhood . 4 Chapter 2 The Will to Walk . 8 Chapter 3 Photographs New Opportunities. 12 Every effort has been made to secure permission and provide appropriate credit for photographic material. The publisher deeply regrets any omission and pledges to correct errors called to its attention in subsequent editions. Chapter 4 Unless otherwise acknowledged, all photographs are the property of Pearson The 1960 Olympics . 16 Education, Inc. Photo locators denoted as follows: Top (T), Center (C), Bottom (B), Left (L), Right (R), Background (Bkgd) Chapter 5 Helping Others . 20 Opener Jerry Cooke/Corbis; 1 ©AP Images; 5 Hulton Archive/Getty Images; 6 Stan Wayman/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images; 7 Margaret Bourke-White/Time Life Pictures/ Getty Images; 8 ©AP Images; 9 Francis Miller/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images; 10 ©iStockphoto; 11 Mark Humphrey/©AP Images; 12 John J. -

RESULTS 400 Metres Women - Final

Moscow (RUS) World Championships 10-18 August 2013 RESULTS 400 Metres Women - Final RESULT NAME COUNTRY AGE DATE VENUE World Record 47.60 Marita KOCH GDR 28 6 Oct 1985 Canberra Championships Record 47.99 Jarmila KRATOCHVÍLOVÁ TCH 32 10 Aug 1983 Helsinki World Leading 49.33 Amantle MONTSHO BOT 30 19 Jul 2013 Monaco TEMPERATURE HUMIDITY START TIME 21:18 21° C 60 % Final 12 August 2013 PLACE BIB NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH LANE RESULT REACTION Fn 1 379 Christine OHURUOGU GBR 17 May 84 4 49.41 NR 0.247 Кристин Охуруогу 17 мая 84 2 170 Amantle MONTSHO BOT 04 Jul 83 5 49.41 0.273 Амантле Монтшо 04 июля 83 3 735 Antonina KRIVOSHAPKA RUS 21 Jul 87 8 49.78 0.209 Антонина Кривошапка 21 июля 87 4 518 Stephanie MCPHERSON JAM 25 Nov 88 2 49.99 0.198 Стефани МакФерсон 25 нояб . 88 5 916 Natasha HASTINGS USA 23 Jul 86 3 50.30 0.163 Наташа Хастингс 23 июля 86 6 930 Francena MCCORORY USA 20 Oct 88 6 50.68 0.241 Франчена МакКорори 20 окт . 88 7 751 Kseniya RYZHOVA RUS 19 Apr 87 7 50.98 0.195 Ксения Рыжова 19 апр . 87 8 514 Novlene WILLIAMS-MILLS JAM 26 Apr 82 1 51.49 0.276 Новлин Уильямс -Миллс 26 апр . 82 ALL-TIME TOP LIST SEASON TOP LIST RESULT NAME Venue DATE RESULT NAME Venue DATE 47.60 Marita KOCH (GDR) Canberra 6 Oct 85 49.33 Amantle MONTSHO (BOT) Monaco 19 Jul 13 47.99 Jarmila KRATOCHVÍLOVÁ (TCH) Helsinki 10 Aug 83 49.41 Christine OHURUOGU (GBR) Moscow 12 Aug 13 48.25 Marie-José PÉREC (FRA) Atlanta, GA 29 Jul 96 49.57 Antonina KRIVOSHAPKA (RUS) Moskva 15 Jul 13 48.27 Olga VLADYKINA-BRYZGINA (UKR) Canberra 6 Oct 85 49.80 Kseniya RYZHOVA (RUS) Cheboksary -

Tennessee Track & Field

TENNESSEE TRACK & FIELD 2019-20 TENNESSEE TRACK & FIELD RECORD BOOK / UTSPORTS.COM / @VOL_TRACK 1 TENNESSEE TRACK & FIELD TABLE OF CONTENTS COACHING HISTORY ALL-TIME ROSTER/LETTERMEN All-Time Women’s Head Coaches 2 All-Time Women’s Roster 61-63 All-Time Men’s Head Coaches 3-4 All-Time Men’s Lettermen 64-67 Early History of Tennessee Track & Field 68 NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS Women’s Team National Championships 5-6 YEAR-BY-YEAR Men’s Team National Championships 7-8 Women’s Results 69-82 All-Time National Championship Leaderboard 9 Men’s Results 83-102 Women’s Individual National Champions 10 Men’s Individual National Champions 11 FACILITIES & RECORDS Tom Black Track Records 103 THE SEC Tennessee’s SEC Championship Leaderboard 12 TENNESSEE MEET HISTORY UT’s SEC Team Championships 12 Tennessee Relays Records 104 All-Time Women’s SEC Indoor Champions 13 Tony Wilson Award Winners 105 All-Time Women’s SEC Outdoor Champions 14 UT Women At The Penn Relays 106 All-Time Men’s SEC Indoor Champions 15-16 UT Men At The Penn Relays 107 All-Time Men’s SEC Outdoor Champions 17-18 ALL-AMERICANS All-American Leaderboard 19 Women’s All-Americans 20-23 Women’s All-Americans (By Event) 24-26 Men’s All-Americans 27-31 Men’s All-Americans (By Event) 32-34 TENNESSEE OLYMPIANS Olympians By Year 35-36 Olympic Medal Count/Stats 36 SCHOOL RECORDS/TOP TIMES LISTS Women’s Indoor Records (All-Time/Freshman) 37 Women’s Outdoor Records (All-Time/Freshman) 38 Men’s Indoor All-Time Records 39 Men’s Indoor Freshman Records 40 Men’s Outdoor All-Time Records 41 Men’s Outdoor -

1965 December, Oracle

,':--, r., cd " " <IJ ,c/" ••L" -"' 0-: ,~ c," [d r:; H "": c, q"" r~., " "'-',' oj G'" ::0.-; "0' -,-I ,..--1 (0 m -," h (71" I--J ,-0 0 ,r:; :1::; 1.":', 0 C'., 'J) r.:" '" ('J -cr; m -r-! r., !:-I ~"\ 'rJ " r~] ~.0 PJ '" ,-I H" "'''''(' OMEGA PSI PHI FRATERNITY. Inc. I Notes J1J:om the Bditoi (Founded November 17, 1911) ReTURN OF PHOTOS FOUNDERS Deal' Brothel's: PROF. FRANK COLEMAN 1232 Girard Street, N.E., Wash., D.C, We receive numeroUs requests for return DR. OSCAR J, COOPER 1621 W. Jefferson St., Phila., Fa. DR. ERNEST E. JUST . .' .,........ • . .. Deceased of photos .. In most instances we make REV. EDGAR ~ LOVE ... 2416 Montebelo Terrace, BaIt., Md. an -all out effort to comply with your wishes. This however; entai'ls an expense GRAND OFFICERS that is not computible to our budget. With GEORGE E, MEARES, Grand BasUeus , .... 155 Willoughby Ave., Brooklyn, N,Y. the continllous ell.pansion of the "Oracle", ELLIS F. CORBETT, 1st Vice G"and BasliellS IllZ Benbow Road, Greensboro, N.C, DORSEY C, MILLER, 2nd Vice Grand Baslleus .. 727 W. 5th Street, Ocala, Fla, we find that We can no lon-gel' absorb WALTER H. RIDDICK, Grand Keeper of ReeD rels & Seal 1038 Chapel St., Norfoll~, Va, this cost, Thus we are requesting. that JESSE B. BLA YTON, SR., Grand Keeper of Finance :3462 Del Mar Lane, N.W., Atlanta, Ga. in the future, requests for return of photos AUDREY PRUITT, Editor of the ORACLE.. 1123 N,E, 4th St., Oklahoma City, Olda. MARION W. GARNETT, Grand Counselor " 109 N. -

The History of the Pan American Games

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1964 The iH story of the Pan American Games. Curtis Ray Emery Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Emery, Curtis Ray, "The iH story of the Pan American Games." (1964). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 977. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/977 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been 65—3376 microfilmed exactly as received EMERY, Curtis Ray, 1917- THE HISTORY OF THE PAN AMERICAN GAMES. Louisiana State University, Ed.D., 1964 Education, physical University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE HISTORY OF THE PAN AMERICAN GAMES A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education m The Department of Health, Physical, and Recreation Education by Curtis Ray Emery B. S. , Kansas State Teachers College, 1947 M. S ., Louisiana State University, 1948 M. Ed. , University of Arkansas, 1962 August, 1964 PLEASE NOTE: Illustrations are not original copy. These pages tend to "curl". Filmed in the best possible way. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS, INC. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study could not have been completed without the close co operation and assistance of many individuals who gave freely of their time. -

Tom Black Track Records

TENNESSEE TRACK & FIELD TOM BLACK TRACK RECORDS WOMEN’S RECORDS MEN’S RECORDS EVENT MARK NAME AFFILIATION DATE EVENT MARK NAME AFFILIATION DATE 100m 10.92 Aleia Hobbs LSU 5-13-18 100m 9.8h Jeff Phillips Athletics West 5-22-82 200m 22.17 Merlene Ottey L.A. Naturite 6-20-82 10.02 Michael Green adidas 4-11-97 400m 50.24 Maicel Malone Asics International TC 6-17-94 200m 20.06 Justin Gatlin Tennessee 4-12-02 800m 2:00.27 Inez Turner SW Texas State 6-02-95 400m 44.28 Nathon Allen Auburn 5-13-18 1500m 4:03.37 Mary Decker-Tabb Athletics West 6-20-82 800m 1:44.85 David Patrick Athletics West 6-21-83 3000m 8:52.26 Brenda Webb Athletics West 5-21-83 1,500m 3:34.92 Steve Scott Sub 4 TC 6-20-82 5000m 15:22.76 Brenda Webb Team Adidas 4-13-84 Mile 3:57.7 Marty Liquori Villanova 6-21-69 10,000m 32:23.76 Olga Appell Reebok RC 6-17-94 3,000m 8:14.01 Jacob Choge Middle Tennessee 3-25-17 100mH 12.40 J. Camacho-Quinn Kentucky 5-13-18 Steeple 8:21.48 Jim Svenoy Texas-El Paso 6-2-95 400mH 52.75 Sydney McLaughlin Kentucky 5-13-18 5,000m 13:20.39 Todd Williams adidas 4-11-97 2000m SC 6:58.85 Gina Wilbanks Athletes in Action USA 6-17-94 10,000m 27:25.82 Simon Chemoiywo Kenya 4-6-95 3000m SC 10:04.33 Ebba Stenbeck Toledo 5-27-06 5,000m Walk 20:41.00 Jim Heiring Unattached 4-10-81 10,000m walk 45:01.96 Teresa Vaill Unattached 6-16-94 10,000m Walk 46:50.6 Timothy Lewis New York AC 6-17-80 20,000m walk 1:28:35.87 Allen James Athletes in Action 6-13-94 4x100m Relay 42.05 ---------------- LSU 5-13-18 110mH 13.15 Grant Holloway Florida 5-13-18 (Mikiah Brisco, Kortnei Johnson, Rachel Misher, Aleia Hobbs) 400mH 48.38 Danny Harris Athletic West 5-23-87 4x200m Relay 1:30.76 ---------------- Kentucky 4-14-18 (Sydney McLaughlin, Jasmin Camacho-Quinn, Kayelle Clarke, Celera Barnes) 4x100mR 38.08 ---------------- America’s Team 4-14-18 4x400m Relay 3:25.99 ---------------- Kentucky 5-13-18 (Christian Coleman, Justin Gatlin, Ronnie Baker, Mike Rogers) (Faith Ross, J. -

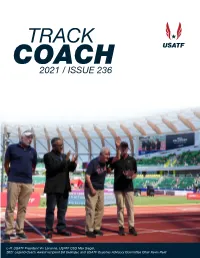

2021 / Issue 236

2021 / ISSUE 236 L-R: USATF President Vin Lananna, USATF CEO Max Siegel, 2021 Legend Coach Award recipient Bill Dellinger, and USATF Coaches Advisory Committee Chair Kevin Reid TRACK COACH Summer 2021 — 236 The official technical LOW GLYCOGEN TRAINING . 7520 publication of VILLANOVA ROUNDTABLE — REMINISCING ABOUT USA Track & Field THE “JUMBO YEARS” . 7522 VISUAL SENSORY DEPRIVATION (VSD) . 7533 TRAINING VS . REHABIILITION . 7541 USATF COACHING EDUCATION . 7544 TRACK FROM THE EDITOR COACH RUSS EBBETS FORMERLY TRACK TECHNIQUE 236 — SUMMER 2021 ALL THE WORLD’S A The official technical STAGE publication of USA Track & Field ED FOX......................................PUBLISHER RUSS EBBETS...................................EDITOR When Aristotle sat down to write the rules of drama some 2500 years TERESA TAM.........PRODUCTION & DESIGN ago, I doubt he gave much thought to relay racing. His Poetics has FRED WILT.......................FOUNDING EDITOR been used by writers and authors since that time to construct plays, movies and television programs that have entertained millions and millions of people worldwide. PUBLICATION But if one were to somehow get Aristotle to attend the Penn Relays Track Coach is published quarterly by on a Saturday afternoon in late April for an hour or so I think he’d be Track & Field News, 2570 W. El Camino Real, #220, asking to borrow someone’s cell to send a text back to his teacher, Mountain View, CA 94040 USA. Plato with the short note, “I have a new idea.” The Fall 2021 issue (No. 237) According to Aristotle a dramatic production consists of six things: of Track Coach will be e-mailed to spectacle, characters, plot, melody, diction and thought. -

Barbara Jones Slater

Tennessee State University Digital Scholarship @ Tennessee State University Tennessee State University Olympians Tennessee State University Olympic History 6-2020 Barbara Jones Slater Julia Huskey Tennessee State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.tnstate.edu/tsu-olympians Part of the Sports Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Huskey, Julia, "Barbara Jones Slater" (2020). Tennessee State University Olympians. 10. https://digitalscholarship.tnstate.edu/tsu-olympians/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Tennessee State University Olympic History at Digital Scholarship @ Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tennessee State University Olympians by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship @ Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Barbara Jones (Slater) Barbara Jones (Slater) (born March 26, 1937 in Chicago), a Tigerbelle from 1957 to 1961 and a 1961 graduate of Tennessee State, was a member of the 1952 and 1960 Olympic-champion 4 x 100 meter relay teams, both of which set world records. She remains the youngest Olympic track gold medalist ever, at age fifteen, and she was a frequent member of the American 4 x 100 meter relay team that dominated 1950s competition. She was also part of three of TSU’s Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) national-championship winning teams1. (In the years prior to highly- organized intercollegiate sports, the AAU championship was the most important national-level competition for women.) In addition to her victories as a member of the national and TSU teams, Jones had a number of individual victories in the 100 meters/100 yards: the AAU national championship in 1953, 1954, and 19572, the Pan American Games in 1955, and the USA-USSR dual meet in 19583 and 1959, when the meet “rivaled the Olympic Games in international and domestic importance”4. -

Directors to Consider Moratorium on Condos Zinsser Out, Race Open

H<[«rb < •;; > ■ ■' < rt ■i-'-"* ,«r%' You Can Be a Winner Wmsm d You can win $750 in The Herald’s Prizeweek ^..ii/-»‘ -'X.. Puzzle. If you are a Herald subscriber, another $25 will be added to your winnings. The Puzzle PBP appears each Saturday in the TV Spotlight sec tion. mi , ■ Directors To Consider Moratorium on Condos MANCHESTER-The Board of sider what is happening in said. which ask "Has a condominium con Directors will consider placing a 90- Manchester. Earlier both Mrs. Weinberg, and version affected you? Or are you day moratorium on condominium “When someone proposes a sub Stephen Cassano had opposed placing next?” They will be distributed division, we have regulations to deal restrictions on condominium conver among the town apartment com ■ :’'X % conversions at its March 11 meeting. The ordinance, which a with it. With this situation we have to sions saying it would be public in plexes this weekend. The leaflets _Manchester advocacy group called for be just as careful to protect the terference on private rights. Mrs. also urge tenants to attend this S. two weeks ago, was proposed by public.”,.. Weinberg said she still believed Tueday’s board meeting. Democratic directors Barbara The proposed ordinance came two “Someone who owns a piece of Cassano has said he and Mrs. Weinberg and Stephen Cassano. They days after a meeting of the property should be allowed to do Weinberg proposed the ordinance have requested a public hearing on Manchester Citizens for Social what they want with it. ” But she because of complaints from tenants ?|4ia the proposition. -

Wilma Rudolph and the TSU Tigerbelles

Leaders of Afro-American N ashville Wilma Rudolph and the TSU Tigerbelles The Tigerbelles Women’s Track Club at Tennessee Wilma G. Rudolph won the James E. SulIivan Award State University became the state’s most in 1961, the year her father died. She was received internationally accomplished athletic team. The by President John F. Kennedy. In 1962 Rudolph sprinters won some 23 Olympic medals, more than retired from track and field and completed goodwill any other sports team in Tennessee history. Mae tours abroad before returning to ClarksvilIe. There Faggs and Barbara Jones became the first Olympic she married Robert Eldridge, and they had two sons medal winning Tigerbelles in 1952. The Tigerbelles and two daughters: Yolanda, Djuana, Robert, and won another medal in 1956. Eventually, the Gold Xurry. After teaching second grade in a Clarksville Medal winners included Edith McGuire, Madeline elementary school, Rudolph left to take several jobs, Manning, Barbara Jones, Martha Hudson, Lucinda later settling in Indianapolis for ten years. Although Williams, Chandra Chesseborough (2), Wilma a star and America’s first female athlete to be so Rudolph (3) and Wyomia Tyus (3). Tyus became the honored, Wilma Rudolph’s life was “no crystal first athlete to win Gold Medals in the sprints in two stair." In her book, Wilma: The Storv of Wilma consecutive Olympiads (1964 and 1968), but the first Rudolph (1977), Rudolph said: “I was besieged with star of the TigerbelIes was Wilma Goldean Rudolph. money problems; people were always expecting me to be a star, but I wasn’t making the money to live Wilma G.