Yoga in the Modern World: the Es Arch for the "Authentic" Practice Grace Heerman University of Puget Sound

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Music Academy, Madras 115-E, Mowbray’S Road

Tyagaraja Bi-Centenary Volume THE JOURNAL OF THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS A QUARTERLY DEVOTED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF THE SCIENCE AND ART OF MUSIC Vol. XXXIX 1968 Parts MV srri erarfa i “ I dwell not in Vaikuntha, nor in the hearts of Yogins, nor in the Sun; (but) where my Bhaktas sing, there be I, Narada l ” EDITBD BY V. RAGHAVAN, M.A., p h .d . 1968 THE MUSIC ACADEMY, MADRAS 115-E, MOWBRAY’S ROAD. MADRAS-14 Annual Subscription—Inland Rs. 4. Foreign 8 sh. iI i & ADVERTISEMENT CHARGES ►j COVER PAGES: Full Page Half Page Back (outside) Rs. 25 Rs. 13 Front (inside) 20 11 Back (Do.) „ 30 „ 16 INSIDE PAGES: 1st page (after cover) „ 18 „ io Other pages (each) „ 15 „ 9 Preference will be given to advertisers of musical instruments and books and other artistic wares. Special positions and special rates on application. e iX NOTICE All correspondence should be addressed to Dr. V. Raghavan, Editor, Journal Of the Music Academy, Madras-14. « Articles on subjects of music and dance are accepted for mblication on the understanding that they are contributed solely o the Journal of the Music Academy. All manuscripts should be legibly written or preferably type written (double spaced—on one side of the paper only) and should >e signed by the writer (giving his address in full). The Editor of the Journal is not responsible for the views expressed by individual contributors. All books, advertisement moneys and cheques due to and intended for the Journal should be sent to Dr. V. Raghavan Editor. Pages. -

I on an Empty Stomach After Evacuating the Bladder and Bowels

• I on a Tllt' Bi11lr· ol' \lodt•nJ Yoga-It� Philo�opl1� and Prad il't' -hv thr: World" s Fon-·mo �l 'l'r·ar·lwr B • I< . S . IYENGAR \\ it h compldc· dt·!wription� and illustrations of all tlw po �tun·� and bn·athing techniqn··� With More than 600 Photographs Positioned Next to the Exercises "For the serious student of Hatha Yoga, this is as comprehensive a handbook as money can buy." -ATLANTA JOURNAL-CONSTITUTION "The publishers calls this 'the fullest, most practical, and most profusely illustrated book on Yoga ... in English'; it is just that." -CHOICE "This is the best book on Yoga. The introduction to Yoga philosophy alone is worth the price of the book. Anyone wishing to know the techniques of Yoga from a master should study this book." -AST RAL PROJECTION "600 pictures and an incredible amount of detailed descriptive text as well as philosophy .... Fully revised and photographs illustrating the exercises appear right next to the descriptions (in the earlier edition the photographs were appended). We highly recommend this book." -WELLNESS LIGHT ON YOGA § 50 Years of Publishing 1945-1995 Yoga Dipika B. K. S. IYENGAR Foreword by Yehudi Menuhin REVISED EDITION Schocken Books New 1:'0rk First published by Schocken Books 1966 Revised edition published by Schocken Books 1977 Paperback revised edition published by Schocken Books 1979 Copyright© 1966, 1968, 1976 by George Allen & Unwin (Publishers) Ltd. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

Yoga Practices As Identity Capital

MÅNS BROO Yoga practices as identity capital Preliminary notes from Turku, Finland s elsewhere in Finland, different types of yoga practices are popular in the Acity of Åbo/Turku. But how do practitioners view their own relationship to their practice, and further, what do they feel that they as individuals gain from it? Through in-depth interviews with yoga teachers in the city of Turku and using the theoretical framework of social psychologists James E. Côte’s and Charles G. Levine’s (2002) concept of identity capital, I wish to examine ways in which individuals, in what could be called a post-secular society, construct a meaningful sense of self and of individual agency. The observations offered in this article represent preliminary notes for a larger work on yoga in Turku, conducted at the ‘Post-Secular Culture and a Changing Religious Landscape’ research project at Åbo Akademi University, devoted to qualitative and eth- nographic investigations of the changing religious landscape in Finland. But before I go on to my theory and material, let me just briefly state some- thing about yoga in Finland in general and in the town of Turku in particular. Turku may not be the political capital of Finland any longer, but is by far the oldest city in the country, with roots going back to the thirteenth century. However, as a site of yoga practice, Turku has a far shorter history than this. As in many other Western countries, the first people in Finland who talked about yoga as a beneficial practice Westerners might take up rather than just laugh at as some weird oriental custom were the theosophists. -

University of California Riverside

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Choreographers and Yogis: Untwisting the Politics of Appropriation and Representation in U.S. Concert Dance A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Critical Dance Studies by Jennifer F Aubrecht September 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Jacqueline Shea Murphy, Chairperson Dr. Anthea Kraut Dr. Amanda Lucia Copyright by Jennifer F Aubrecht 2017 The Dissertation of Jennifer F Aubrecht is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I extend my gratitude to many people and organizations for their support throughout this process. First of all, my thanks to my committee: Jacqueline Shea Murphy, Anthea Kraut, and Amanda Lucia. Without your guidance and support, this work would never have matured. I am also deeply indebted to the faculty of the Dance Department at UC Riverside, including Linda Tomko, Priya Srinivasan, Jens Richard Giersdorf, Wendy Rogers, Imani Kai Johnson, visiting professor Ann Carlson, Joel Smith, José Reynoso, Taisha Paggett, and Luis Lara Malvacías. Their teaching and research modeled for me what it means to be a scholar and human of rigorous integrity and generosity. I am also grateful to the professors at my undergraduate institution, who opened my eyes to the exciting world of critical dance studies: Ananya Chatterjea, Diyah Larasati, Carl Flink, Toni Pierce-Sands, Maija Brown, and rest of U of MN dance department, thank you. I thank the faculty (especially Susan Manning, Janice Ross, and Rebekah Kowal) and participants in the 2015 Mellon Summer Seminar Dance Studies in/and the Humanities, who helped me begin to feel at home in our academic community. -

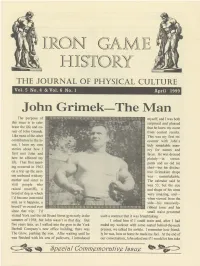

HOW STEVE REEVES TRAINED by John Grimek

IRON GAME HISTORY VOL.5No.4&VOL. 6 No. 1 IRON GAME HISTORY ATRON SUBSCRIBERS THE JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL CULTURE P Gordon Anderson Jack Lano VOL. 5 NO. 4 & VOL. 6 NO. 1 Joe Assirati James Lorimer SPECIAL DOUBL E I SSUE John Balik Walt Marcyan Vic Boff Dr. Spencer Maxcy TABLE OF CONTENTS Bill Brewer Don McEachren Bill Clark David Mills 1. John Grimek—The Man . Terry Todd Robert Conciatori Piedmont Design 6. lmmortalizing Grimek. .David Chapman Bruce Conner Terry Robinson 10. My Friend: John C. Grimek. Vic Boff Bob Delmontique Ulf Salvin 12. Our Memories . Pudgy & Les Stockton 4. I Meet The Champ . Siegmund Klein Michael Dennis Jim Sanders 17. The King is Dead . .Alton Eliason Mike D’Angelo Frederick Schutz 19. Life With John. Angela Grimek Lucio Doncel Harry Schwartz 21. Remembering Grimek . .Clarence Bass Dave Draper In Memory of Chuck 26. Ironclad. .Joe Roark 32. l Thought He Was lmmortal. Jim Murray Eifel Antiques Sipes 33. My Thoughts and Reflections. .Ken Rosa Salvatore Franchino Ed Stevens 36. My Visit to Desbonnet . .John Grimek Candy Gaudiani Pudgy & Les Stockton 38. Best of Them All . .Terry Robinson 39. The First Great Bodybuilder . Jim Lorimer Rob Gilbert Frank Stranahan 40. Tribute to a Titan . .Tom Minichiello Fairfax Hackley Al Thomas 42. Grapevine . Staff James Hammill Ted Thompson 48. How Steve Reeves Trained . .John Grimek 50. John Grimek: Master of the Dance. Al Thomas Odd E. Haugen Joe Weider 64. “The Man’s Just Too Strong for Words”. John Fair Norman Komich Harold Zinkin Zabo Koszewski Co-Editors . , . Jan & Terry Todd FELLOWSHIP SUBSCRIBERS Business Manager . -

Focus of the Month 2.14

Bobbi Misiti 2201 Market Street Camp HIll, PA 17011 717.443.1119 befityoga.com TOPIC OF THE MONTH February 2014 FROM NOW FORWARD . AND SOME NOTES FROM MAUI Although I am not a “big fan” of the sutras, I do like to study them. Just because something was written as an “ancient text” does not always mean it has merritt . and in just the same way -- because some study proves some scientific “fact”, does not mean it is truth. For example all those years we thought saturated fat was bad for us . it is not! Studies were mis-read, mis-leading, politically adjusted, and “interpretations” seem to benefit some benefactor more than mankind. However I like this little blip from David Life on the very first sutra, in my simple words it basically says: From now on, just allow the yoga to arise naturally in you :) Excerpts from David Life's January 2014 focus of the month -- Jivamukti Yoga Atha yoga-anushasanam (Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra 1:1) Now this is yoga as I have perceived it in the natural world. Atha means “now.” But it’s more than just “now”; it means now in terms of “hereafer,” or “going forward.” The importance of that nuance is that it implies that whatever has been happening will now, hereafer, be different. The word shasanam can be understood as a set of rules, a discipline applied to us from the outside, a set of instructions for what we’re supposed to do next. But when we put the word anu, which literally means “atom,” in front of it, it means the instructions or ways to act that come from the inside. -

Preserving and Protecting Mysore Heritage Tmt

Session – I Preserving And Protecting Mysore Heritage Tmt. Neela Manjunath, Commissioner, Archaeology, Museums and Heritage Department, Bangalore. An introduction to Mysore Heritage Heritage Heritage is whatever we inherit from our predecessors Heritage can be identified as: Tangible Intangible Natural Heritage can be environmental, architectural and archaeological or culture related, it is not restricted to monuments alone Heritage building means a building possessing architectural, aesthetic, historic or cultural values which is identified by the heritage conservation expert committee An introduction to Mysore heritage Mysore was the capital of princely Mysore State till 1831. 99 Location Mysore is to the south-west of Bangalore at a distance of 139 Kms. and is well connected by rail and road. The city is 763 meters above MSL Princely Heritage City The city of Mysore has retained its special characteristics of a ‘native‘princely city. The city is a classic example of our architectural and cultural heritage. Princely Heritage City : The total harmony of buildings, sites, lakes, parks and open spaces of Mysore with the back drop of Chamundi hill adds to the attraction of this princely city. History of Mysore The Mysore Kingdom was a small feudatory of the Vijayanagara Empire until the emergence of Raja Wodeyar in 1578. He inherited the tradition of Vijayanagara after its fall in 1565 A.D. 100 History of Mysore - Dasara The Dasara festivities of Vijayanagara was started in the feudatory Mysore by Raja Wodeyar in 1610. Mysore witnessed an era of pomp and glory under the reign of the wodeyars and Tippu Sultan. Mysore witnessed an all round development under the visionary zeal of able Dewans. -

Ashtanga Yoga As Taught by Shri K. Pattabhi Jois Copyright ©2000 by Larry Schultz

y Ashtanga Yoga as taught by Shri K. Pattabhi Jois y Shri K. Pattabhi Jois Do your practice and all is coming (Guruji) To my guru and my inspiration I dedicate this book. Larry Schultz San Francisco, Califórnia, 1999 Ashtanga Ashtanga Yoga as taught by shri k. pattabhi jois Copyright ©2000 By Larry Schultz All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reprinted without the written permission of the author. Published by Nauli Press San Francisco, CA Cover and graphic design: Maurício Wolff graphics by: Maurício Wolff & Karin Heuser Photos by: Ro Reitz, Camila Reitz Asanas: Pedro Kupfer, Karin Heuser, Larry Schultz y I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Bob Weir of the Grateful Dead. His faithful support and teachings helped make this manual possible. forward wenty years ago Ashtanga yoga was very much a fringe the past 5,000 years Ashtanga yoga has existed as an oral tradition, activity. Our small, dedicated group of students in so when beginning students asked for a practice guide we would TEncinitas, California were mostly young, hippie types hand them a piece of paper with stick figures of the first series with little money and few material possessions. We did have one postures. Larry gave Bob Weir such a sheet of paper a couple of precious thing – Ashtanga practice, which we all knew was very years ago, to which Bob responded, “You’ve got to be kidding. I powerful and deeply transformative. Practicing together created a need a manual.” unique and magical bond, a real sense of family. -

Thriving in Healthcare: How Pranayama, Asana, and Dyana Can Transform Your Practice

Thriving in Healthcare: How pranayama, asana, and dyana can transform your practice Melissa Lea-Foster Rietz, FNP-BC, BC-ADM, RYT-200 Presbyterian Medical Services Farmington, NM [email protected] Professional Disclosure I have no personal or professional affiliation with any of the resources listed in this presentation, and will receive no monetary gain or professional advancement from this lecture. Talk Objectives Provide a VERY brief history of yoga Define three aspects of wellness: mental, physical, and social. Define pranayama, asana, and dyana. Discuss the current evidence demonstrating the impact of pranayama, asana, and dyana on mental, physical, and social wellness. Learn and practice three techniques of pranayama, asana, and dyana that can be used in the clinic setting with patients. Resources to encourage participation from patients and to enhance your own practice. Yoga as Medicine It is estimated that 21 million adults in the United States practice yoga. In the past 15 years the number of practitioners, of all ages, has doubled. It is thought that this increase is related to broader access, a growing body of research on the affects of the practice, and our understanding that ancient practices may hold the key to healing modern chronic diseases. Yoga: A VERY Brief History Yoga originated 5,000 or more years ago with the Indus Civilization Sanskrit is the language used in most Yogic scriptures and it is believed that the principles of the practice were transmitted by word of mouth for generations. Georg Feuerstien divides the history of Yoga into four catagories: Vedic Yoga: connected to ritual life, focus the inner mind in order to transcend the limitations of the ordinary mind Preclassical Yoga: Yogic texts, Upanishads and the Bhagavad-Gita Classical Yoga: The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, the eight fold path Postclassical Yoga: Creation of Hatha (willful/forceful) Yoga, incorporation of the body into the practice Modern Yoga Swami (master) Vivekananda speaks at the Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893. -

Religious, Spiritual, and Secular Identities of Modern Postural Yoga in the Ozarks

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Fall 2015 Bodies Bending Boundaries: Religious, Spiritual, and Secular Identities of Modern Postural Yoga in the Ozarks Kimberley J. Pingatore As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Pingatore, Kimberley J., "Bodies Bending Boundaries: Religious, Spiritual, and Secular Identities of Modern Postural Yoga in the Ozarks" (2015). MSU Graduate Theses. 3010. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3010 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BODIES BENDING BOUNDARIES: RELIGIOUS, SPIRITUAL, AND SECULAR IDENTITIES OF MODERN POSTURAL YOGA IN THE OZARKS A Masters Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts, Religious Studies By Kimberley J. Pingatore December 2015 Copyright 2015 by Kimberley Jaqueline Pingatore ii BODIES BENDING BOUNDARIES: RELIGIOUS, SPIRITUAL, AND SECULAR IDENTITIES OF MODERN POSTURAL YOGA IN THE OZARKS Religious Studies Missouri State University, December 2015 Master of Arts Kimberley J. -

Is a Complete State of Mental, Physical, and Social Well

Bobbi Misiti 834 Market Street Lemoyne, PA 17043 717.443.1119 befityoga.com POSE OF THE MONTH December 2006 Marichyasana B – This pose takes Marichyasana A a step further—you now go from working externally to open and prepare the body to working internally on the organs of the body. Marichyasana B requires the half lotus position which can be difficult to attain if you have knee instabilities, tightness in your hips, or are athletic. Patience must reign as you wait for your hip joint to slowly open up to allow the deep inner work of this posture. Method: From Downward dog hop through to Dandasana. Inhaling place your LEFT leg in half lotus, turning the sole of your foot upward and if your hip allows, moving your heel toward your navel. If you are unable to get your leg safely in half lotus you can drop the foot out of the lotus position and place it by your right buttock (see picture of Jim). With your left leg in half lotus or under your thigh, bend your right knee sliding your foot back toward your hip, allow your right hip to lift off the floor Jim as you roll forward on your sitting bones and ground your left thigh, lean forward sliding your right arm inside your leg and forward (see picture of Abby). You can stay here if you are unable to complete the final step. Leaning forward to lengthen the right waist, keep your right knee in tight to your ribs, get your body as low as possible—ideally hooking your shoulder Misty half way down between your knee and ankle, if your shoulder is close to your shin turn your right palm upward internally rotating the shoulder and reach your right arm behind you, wrap Abby your left arm around your waist and see if your right hand can clasp your left wrist or hook fingers (keeping your right palm turned upward). -

An Introduction to Yoga for Whole Health

WHOLE HEALTH: INFORMATION FOR VETERANS An Introduction to Yoga for Whole Health Whole Health is an approach to health care that empowers and enables YOU to take charge of your health and well-being and live your life to the fullest. It starts with YOU. It is fueled by the power of knowing yourself and what will really work for you in your life. Once you have some ideas about this, your team can help you with the skills, support, and follow up you need to reach your goals. All resources provided in these handouts are reviewed by VHA clinicians and Veterans. No endorsement of any specific products is intended. Best wishes! https://www.va.gov/wholehealth/ An Introduction to Yoga for Whole Health An Introduction to Yoga for Whole Health SUMMARY 1. One of the main goals of yoga is to help people find a more balanced and peaceful state of mind and body. 2. The goal of yoga therapy (also called therapeutic yoga) is to adapt yoga for people who may have a variety of health conditions or needs. 3. Yoga can help improve flexibility, strength, and balance. Research shows it may help with the following: o Decrease pain in osteoarthritis o Improve balance in the elderly o Control blood sugar in type 2 diabetes o Improve risk factors for heart disease, including blood pressure o Decrease fatigue in patients with cancer and cancer survivors o Decrease menopausal hot flashes o Lose weight (See the complete handout for references.) 4. Yoga is a mind-body activity that may help people to feel more calm and relaxed.