Biography/Biografia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pages 4 Rotella, Lot 51 Pagine

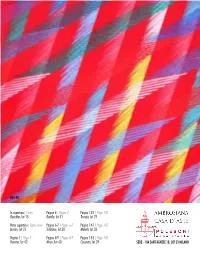

LOT 42 In copertina | Cover Pagine 4 | Pages 4 Pagina 133 | Page 133 Baechler, lot 15 Rotella, lot 51 Turcato, lot 29 Retro copertina | Back cover Pagine 6-7 | Pages 6-7 Pagina 142 | Page 142 Arman, lot 25 Schifano, lot 30 Melotti, lot 33 Pagina 1 | Page 1 Pagine 8-9 | Pages 8-9 Pagina 143 | Page 143 Dorazio, lot 42 Music, lot 60 Cassinari, lot 39 SEDE - VIA SANT’AGNESE 18, 20123 MILANO ASTA ARTE MODERNA E CONTEMPORANEA 10 NOVEMBRE 2020 MILANO, VIA SACCHI 7 – presso LA POSTERIA 23 OTTOBRE - 4 NOVEMBRE, MILANO VIA SANT’AGNESE 18 0 (ORARIO 10.00-19.00 – ESCLUSO FESTIVI E 29 OTTOBRE) PREVIO APPUNTAMENTO 7-8-9 NOVEMBRE, MILANO, VIA SACCHI 7 (ORARIO 10.00-19.00) UNICA SESSIONE MARTEDÌ 10 NOVEMBRE 2020 ORE 16.00 LOTTI 1 - 243 PRESENTAZIONE TELEVISIVA TOP LOTS Lunedì 2/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre Martedì 3/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre Giovedì 5/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre Venerdì 6/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre OFFERTE SCRITTE FINO A LUNEDÌ 9 NOVEMBRE 2020 ORE 15.00 FAX +39 02 40703717 [email protected] È possibile partecipare in diretta on-line inscrivendosi (almeno 24 ore prima) sul nostro sito www.ambrosianacasadaste.com CONSULTAZIONE CATALOGO E MODULISTICA www.ambrosianacasadaste.com da venerdì 23 ottobre 2020 AMBROSIANA CASA D’ASTE / GALLERIA POLESCHI CASA D’ASTE - VIA SANT’AGNESE 18 20123 MILANO - TEL. +39 0289459708 - FAX +39 0240703717 www.ambrosianacasadaste.com • [email protected] LOT 51 338 1226703 5 MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY ART -

Copertina Artepd.Cdr

Trent’anni di chiavi di lettura Siamo arrivati ai trent’anni, quindi siamo in quell’età in cui ci sentiamo maturi senza esserlo del tutto e abbiamo tantissime energie da spendere per il futuro. Sono energie positive, che vengono dal sostegno e dal riconoscimento che il cammino fin qui percorso per far crescere ArtePadova da quella piccola edizio- ne inaugurale del 1990, ci sta portando nella giusta direzione. Siamo qui a rap- presentare in campo nazionale, al meglio per le nostre forze, un settore difficile per il quale non è ammessa l’improvvisazione, ma serve la politica dei piccoli passi; siamo qui a dimostrare con i dati di questa edizione del 2019, che siamo stati seguiti con apprezzamento da un numero crescente di galleristi, di artisti, di appassionati cultori dell’arte. E possiamo anche dire, con un po’ di vanto, che negli anni abbiamo dato il nostro contributo di conoscenza per diffondere tra giovani e meno giovani l’amore per l’arte moderna: a volte snobbata, a volte non compresa, ma sempre motivo di dibattito e di curiosità. Un tentativo questo che da qualche tempo stiamo incentivando con l’apertura ai giovani artisti pro- ponendo anche un’arte accessibile a tutte le tasche: tanto che nei nostri spazi figurano, democraticamente fianco a fianco, opere da decine di migliaia di euro di valore ed altre che si fermano a poche centinaia di euro. Se abbiamo attraversato indenni il confine tra due secoli con le sue crisi, è per- ché l’arte è sì bene rifugio, ma sostanzialmente rappresenta il bello, dimostra che l’uomo è capace di grandi azzardi e di mettersi sempre in gioco sperimen- tando forme nuove di espressione; l’arte è tecnica e insieme fantasia, ovvero un connubio unico e per questo quasi magico tra terra e cielo. -

Catalogo 144 TENDENZE INFORMALI

COMUNE DI BRESCIA CIVICI MUSEI D’ARTE E STORIA PROVINCIA DI BRESCIA ASSOCIAZIONE ARTISTI BRESCIANI TENDENZE INFORMALI DAGLI ANNI CINQUANTA AI PRIMI ANNI classici del contemporaneo SETTANTA NELLE COLLEZIONI BRESCIANE mostra a cura di Alessandra Corna Pellegrini 144 aab - vicolo delle stelle 4 - brescia 22 settembre - 17 ottobre 2007 orario feriale e festivo 15.30 - 19.30 edizioni aab lunedì chiuso L’AAB è orgogliosa di inaugurare la stagione 2007/2008 con una prestigiosa esposizione, di rilievo certamente non solo locale, che propone opere di artisti fra i più rappresentativi dell’Informale. La mostra prosegue la fortunata serie “Classici del contemporaneo” dedicata al collezionismo della nostra provincia, che ha già proposto artisti come Kolàr, Demarco, Fontana, Munari, Birolli, Dorazio, Vedova, Fieschi, Adami, Baj ed esponenti della Nuova Figurazione. La curatrice della rassegna, la storica dell’arte Alessandra Corna Pellegrini, ha selezionato un nucleo essenziale di opere (34) che rappresentano esempi molto significativi dell’esperienza e del linguaggio di un movimento pur tanto complesso e così difficile da circoscrivere come l’Informale e dimostrano l’alta qualità delle collezioni bresciane, sia pubbliche sia private. L’impegno dell’AAB, scientifico organizzativo finanziario, può ben essere documentato dall’importanza internazionale degli autori proposti, da Dubuffet Mathieu Schneider a Afro Basaldella Corpora Dorazio Fontana Morlotti Santomaso Scanavino Scialoja Tancredi Turcato. L’esposizione, come è prassi costante dell’Associazione, -

Export / Import: the Promotion of Contemporary Italian Art in the United States, 1935–1969

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2016 Export / Import: The Promotion of Contemporary Italian Art in the United States, 1935–1969 Raffaele Bedarida Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/736 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] EXPORT / IMPORT: THE PROMOTION OF CONTEMPORARY ITALIAN ART IN THE UNITED STATES, 1935-1969 by RAFFAELE BEDARIDA A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 RAFFAELE BEDARIDA All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ___________________________________________________________ Date Professor Emily Braun Chair of Examining Committee ___________________________________________________________ Date Professor Rachel Kousser Executive Officer ________________________________ Professor Romy Golan ________________________________ Professor Antonella Pelizzari ________________________________ Professor Lucia Re THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT EXPORT / IMPORT: THE PROMOTION OF CONTEMPORARY ITALIAN ART IN THE UNITED STATES, 1935-1969 by Raffaele Bedarida Advisor: Professor Emily Braun Export / Import examines the exportation of contemporary Italian art to the United States from 1935 to 1969 and how it refashioned Italian national identity in the process. -

Carroll Barnes (March 1–March 15) Carroll Barnes (1906–1997) Worked in Various Careers Before Turning His Attention to Sculpture Full Time at the Age of Thirty

1950 Sculpture in Wood and Stone by Carroll Barnes (March 1–March 15) Carroll Barnes (1906–1997) worked in various careers before turning his attention to sculpture full time at the age of thirty. His skills earned him a position as a professor of art at the University of Texas and commissions from many public and private institutions. His sculptures are created in various media, such as Lucite and steel. This exhibition of the California-based artist’s work presented thirty-seven of his sculptures. Barnes studied with Carl Milles (1875– 1955) at the Cranbrook Academy of Art. [File contents: exhibition flier] Color Compositions by June Wayne (March) June Wayne’s (1918–2011) work received publicity in an article by Jules Langsner, who praised her for developing techniques of drawing the viewer’s eye through imagery and producing a sense of movement in her subjects. Her more recent works (as presented in the show) were drawn from the dilemmas to be found in Franz Kafka’s works. [File contents: two articles, one more appropriate for a later show of 1953 in memoriam Director Donald Bear] Prints by Ralph Scharff (April) Sixteen pieces by Ralph Scharff (1922–1993) were exhibited in the Thayer Gallery. Some of the works included in this exhibition were Apocrypha, I Hate Birds, Walpurgisnacht, Winter 1940, Nine Cats, and Four Cows and Tree Oranges. Watercolors by James Couper Wright (April 3–April 15) Eighteen of James Couper Wright’s (1906–1969) watercolors were presented in this exhibition. Wright was born in Scotland, but made his home in Southern California for the previous eleven years. -

Werner Haftmann As the Director of the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin

692 V. Benedettino УДК: 7.036(4), 069.02:7 ББК: 79.17 А43 DOI: 10.18688/aa200-5-66 V. Benedettino Werner Haftmann as the Director of the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin (1967–1974): Survey of the Curatorial Concept in the West German National Modern Art Gallery during the Cold War The following paper will present preliminary results related to key aspects of Werner Haft- mann’s curatorial activity as the director of the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin from 1967 un- til 1974. The archival research was undertaken in several public archives in Germany and Italy in the frame of my Ph. D. at Universität Heidelberg and École du Louvre in Paris1. Firstly, Haftmann’s biography will be briefly outlined in order to contextualize his career as an art historian in the first half of the 20th century in Germany, Italy, and after World War II in West Germany. Afterwards, the circumstances of his appointment as the director of the Neue Na- tionalgalerie, built by the renowned architect Mies van der Rohe in West Berlin from 1965 until 1968, will be discussed. Finally, Haftmann’s curatorial concept concerning temporary exhibitions and artworks purchase policy, in addition to his statement about the mission of a national modern art museum will be highlighted. The professional career of Werner Gustav Haftmann (1912–1999) must be analysed in the light of the turbulent political and historical events that occurred in Germany during the 20th century. The art historian started a successful career in the 1930s during the repressive Nazi regime and consolidated it after World War II, in the time of West Germany’s recon- struction. -

Roma 1950 - 1965” an Exhibition Curated by Germano Celant Presented by Fondazione Prada 23 March – 27 May 2018 Prada Rong Zhai, Shanghai

“ROMA 1950 - 1965” AN EXHIBITION CURATED BY GERMANO CELANT PRESENTED BY FONDAZIONE PRADA 23 MARCH – 27 MAY 2018 PRADA RONG ZHAI, SHANGHAI “Roma 1950-1965,” conceived and curated by Germano Celant and presented by Fondazione Prada, will open to the public from 23 March to 27 May 2018 within the spaces of Prada Rong Zhai in Shanghai. The exhibition explores the exciting cultural climate and lively art scene that developed in Rome during the period following the World War II, bringing together over 30 paintings and sculptures by artists including Carla Accardi, Afro Basaldella, Mirko Basaldella, Alberto Burri, Giuseppe Capogrossi, Ettore Colla, Pietro Consagra, Piero Dorazio, Nino Franchina, Gastone Novelli, Antonio Sanfilippo, Toti Scialoja and Giulio Turcato. Within a historical context characterized by the Italian economic boom and an increasing industrialization, the intellectual and artistic debate focused on notions of linguistic renewal and political commitment. In Italy, from the mid-1940s, innovation was embodied from a literary and cinematographic perspective through the neorealist movement, represented by film directors such as Luchino Visconti, Roberto Rossellini and Vittorio De Sica, while writers and intellectuals like Elio Vittorini and Cesare Pavese created an extraordinary period of experimentalism and international openness. In the art scene, people witnessed the spread of ferocious debates and polemics, as well as the proliferation of opposing groups and theoretical positions. Rome was one of the most vital epicenters of this clash of ideas which translated into a rethinking of idelogical realism, promoted by artistic figures like Renato Guttuso and Giacomo Manzù, as well as into an attempt to reconcile collective life with individual experience, abstraction with political militancy, art with science. -

Tate Papers Issue 12 2009: Walter Grasskamp

Tate Papers Issue 12 2009: Walter Grasskamp http://www.tate.org.uk/research/tateresearch/tatepapers/09autumn/gras... ISSN 1753-9854 TATE’S ONLINE RESEARCH JOURNAL Landmark Exhibitions Issue To Be Continued: Periodic Exhibitions ( documenta , For Example) Walter Grasskamp Between 1978 and 1983 I worked for the German art magazine Kunstforum International that planned to publish its fiftieth volume in 1982, the year of the seventh documenta . I proposed that we should dedicate the issue to the history of the documenta , combining our minor jubilee with the major event that had re-established West Germany as an international forum of modern art in 1955. Having heard that a documenta archive existed in Kassel, I expected that little work would be needed. ‘Just grab the photos and run’, I thought, but I was wrong. The archive in Kassel turned out to be quite a respectable library, consisting of catalogues and books on modern and contemporary art, most of them debris from the previous six exhibitions sent in by gallerists and artists, or bought for, and left behind by, the various exhibition committees. More appropriate to the name and function of an archive was an impressive collection of press clippings and reviews, stored in folders that also contained letters, drafts and other material written by the founders and curators of the first six documentas . When I asked for installation photographs of the exhibitions, however, I was shown a metal locker in the corner of the room, brim-full of envelopes and files containing heaps of photographs and papers. But it seemed that the locker had been opened for me for the first time in years: a quick examination showed that most of the photographs were unsorted and had no comments, or only laconic comments, on the back, some not even giving the number of the documenta in which they had been taken. -

5.7 Apparato Documentario E Iconografico N. 4

5.7 Apparato documentario e iconografico n. 4 a) scheda della mostra Titolo: documenta III. Internationale Ausstellung, Kassel Periodo: 27 giugno - 5 ottobre 1964 Società titolare: documenta GmbH, Kassel Direttore artistico: Arnold Bode Comitato per la pittura e la scultura: Arnold Bode, Gerhard Bott, Herbert Freiherr von Buttlar, Will Grohmann, Werner Haftmann, Alfred Hentzen, Erich Herzog, Kurt Martin, Werner Schmalenbach, Heinrich Stünke Eduard Trier, Zoran Kržišnik, Giuseppe Marchiori, Josia Reichhardt, Peter Selz. Comitato per il disegno: Werner Haftmann, Jan Heyligers, Wolf Stubbe, Heinrich Stünke, Eduard Trier Presidente del consiglio: Sindaco Karl Branner; vicepresidente: Presidente del Land Alfred Schneider Allestimenti: Arnold Bode (collaboratori: Rudolf Staege, Lorenz Dombois) Segretario: Theodor Ascher Sedi: Museum Fridericianum, Orangerie, Neue Galerie Opere: 1450 opere; 280 artisti Peasi coinvolti: 21 Visitatori: oltre 200.000 Costi e finanziamenti: - Preventivo 1.400.000 DM - Costi sostenuti: 2.437.000 Dm - Ricavo dagli ingressi: 443.000 DM - Donazioni: 340.000 DM - Altre entrate: 237.000 DM - Contributi: Bund 100.000 DM; Land Hessen: 350.000 DM; Stadt Kassel: 390.000 DM. Cataloghi: - Documenta III: Internationale Austellung, 27. Juni-5. Oktober 1964, Kassel, Alte Galerie, Museum Fridericianum, Band. 1, Malerei, Skulptur, DuMont Schauberg, Köln 1964. - Documenta III: Internationale Austellung, 27. Juni-5. Oktober 1964, Kassel, Alte Galerie, Museum Fridericianum, Band. 2, Handzeichnungen, Hessische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, -

Beyond Nationalism? Blank Spaces at the Documenta 1955 – the Legacy of an Exhibition Between Old Europe and New World Order

Artl@s Bulletin Volume 9 Issue 1 “Other Modernities”: Art, Visual Culture Article 3 and Patrimony Outside the West 2020 Beyond Nationalism? Blank Spaces at the documenta 1955 – The Legacy of an Exhibition Between Old Europe and New World Order Mirl Redmann University of Geneva, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/artlas Part of the African History Commons, Holocaust and Genocide Studies Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, Other German Language and Literature Commons, Other Italian Language and Literature Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Redmann, Mirl. "Beyond Nationalism? Blank Spaces at the documenta 1955 – The Legacy of an Exhibition Between Old Europe and New World Order." Artl@s Bulletin 9, no. 1 (2020): Article 3. This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. This is an Open Access journal. This means that it uses a funding model that does not charge readers or their institutions for access. Readers may freely read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of articles. This journal is covered under the CC BY-NC-ND license. “Other Modernities” Beyond Nationalism? Blank Spaces at the documenta 1955 – The Legacy of an Exhibition Between Old Europe and New World Order Mirl Redmann* Université de Genève Abstract Was the first documenta really beyond nationalism? documenta 1955 has been widely regarded as conciliation for the fascist legacy of the exhibition “Degenerate Art” (1937), and as an attempt to reintegrate Germany into the international arts community. -

2RC Pressrelease

Italian Cultural Institute of Chicago The Doublefold Dream of Art 2RC - Between Artist and Artificer Graphic Works - 1964-1991 Opening: Tuesday, April 1st 6 pm from April 1st to June 3rd 2008 opening hours: 9-1 and 2-5 pm Alexander Calder, Presenza Grafica, 1972. PRESSRELEASE The Istituto Italiano di Cultura of Chicago will host the opening of Doppio Sogno Dell’Art (The Doublefold Dream of Art), a traveling exhibition of prints and engravings of some of the greatest Italian and international contemporary artists of the 20th century, including Alberto Burri, Francesco Clemente, Sam Francis, Henry Moore, Lucio Fontana, George Segal, Alexander Calder. These works have been selected from among the works exhibited in Milan in April 2007 at the Fondazione Arnaldo Pomodoro, under the direction of the renowned curator and art critic Achille Bonito Oliva. The exhibit centers on the history of the famous Roman print studio 2RC which has kept alive the graphic arts tradition for more than forty years. Studio 2RC reproduces masterpieces by established artists and proprietors Valter and Eleonora Rossi are constantly on the lookout for new techniques that will do justice to the artists and their styles. While showcasing the history of this extraordinary print studio, the exhibit traces the international history of graphic design from the 1970s to the present. On display will be engravings by Alberto Burri (known for his signature style, delicate and blood- stained), project plans by Henry Moore, Sam Francis’s explosions of color, George Segal’s casts, and Afro Basaldella’s dreamlike geometries; other artists represented will include Enzo Cucchi, Victor Pasmore, Louise Nevelson, Arnaldo Pomodoro, and others. -

ITALIAN MODERN ART | ISSUE 3: ISSN 2640-8511 Introduction

ITALIAN MODERN ART | ISSUE 3: ISSN 2640-8511 Introduction ITALIAN MODERN ART - ISSUE 3 | INTRODUCTION italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/introduction-3 Raffaele Bedarida | Silvia Bignami | Davide Colombo Methodologies of Exchange: MoMA’s “Twentieth-Century Italian Art” (1949), Issue 3, January 2020 https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/methodologies-of- exchange-momas-twentieth-century-italian-art-1949/ ABSTRACT A brief overview of the third issue of Italian Modern Art dedicated to the MoMA 1949 exhibition Twentieth-Century Italian Art, including a literature review, methodological framework, and acknowledgments. If the study of artistic exchange across national boundaries has grown exponentially over the past decade as art historians have interrogated historical patterns, cultural dynamics, and the historical consequences of globalization, within such study the exchange between Italy and the United States in the twentieth-century has emerged as an exemplary case.1 A major reason for this is the history of significant migration from the former to the latter, contributing to the establishment of transatlantic networks and avenues for cultural exchange. Waves of migration due to economic necessity in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries gave way to the smaller in size but culturally impactful arrival in the U.S. of exiled Jews and political dissidents who left Fascist Italy during Benito Mussolini’s regime. In reverse, the presence in Italy of Americans – often participants in the Grand Tour or, in the 1950s, the so-called “Roman Holiday” phenomenon – helped to making Italian art, past and present, an important component in the formation of American artists and intellectuals.2 This history of exchange between Italy and the U.S.