Tate Papers Issue 12 2009: Walter Grasskamp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pages 4 Rotella, Lot 51 Pagine

LOT 42 In copertina | Cover Pagine 4 | Pages 4 Pagina 133 | Page 133 Baechler, lot 15 Rotella, lot 51 Turcato, lot 29 Retro copertina | Back cover Pagine 6-7 | Pages 6-7 Pagina 142 | Page 142 Arman, lot 25 Schifano, lot 30 Melotti, lot 33 Pagina 1 | Page 1 Pagine 8-9 | Pages 8-9 Pagina 143 | Page 143 Dorazio, lot 42 Music, lot 60 Cassinari, lot 39 SEDE - VIA SANT’AGNESE 18, 20123 MILANO ASTA ARTE MODERNA E CONTEMPORANEA 10 NOVEMBRE 2020 MILANO, VIA SACCHI 7 – presso LA POSTERIA 23 OTTOBRE - 4 NOVEMBRE, MILANO VIA SANT’AGNESE 18 0 (ORARIO 10.00-19.00 – ESCLUSO FESTIVI E 29 OTTOBRE) PREVIO APPUNTAMENTO 7-8-9 NOVEMBRE, MILANO, VIA SACCHI 7 (ORARIO 10.00-19.00) UNICA SESSIONE MARTEDÌ 10 NOVEMBRE 2020 ORE 16.00 LOTTI 1 - 243 PRESENTAZIONE TELEVISIVA TOP LOTS Lunedì 2/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre Martedì 3/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre Giovedì 5/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre Venerdì 6/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre OFFERTE SCRITTE FINO A LUNEDÌ 9 NOVEMBRE 2020 ORE 15.00 FAX +39 02 40703717 [email protected] È possibile partecipare in diretta on-line inscrivendosi (almeno 24 ore prima) sul nostro sito www.ambrosianacasadaste.com CONSULTAZIONE CATALOGO E MODULISTICA www.ambrosianacasadaste.com da venerdì 23 ottobre 2020 AMBROSIANA CASA D’ASTE / GALLERIA POLESCHI CASA D’ASTE - VIA SANT’AGNESE 18 20123 MILANO - TEL. +39 0289459708 - FAX +39 0240703717 www.ambrosianacasadaste.com • [email protected] LOT 51 338 1226703 5 MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY ART -

Copertina Artepd.Cdr

Trent’anni di chiavi di lettura Siamo arrivati ai trent’anni, quindi siamo in quell’età in cui ci sentiamo maturi senza esserlo del tutto e abbiamo tantissime energie da spendere per il futuro. Sono energie positive, che vengono dal sostegno e dal riconoscimento che il cammino fin qui percorso per far crescere ArtePadova da quella piccola edizio- ne inaugurale del 1990, ci sta portando nella giusta direzione. Siamo qui a rap- presentare in campo nazionale, al meglio per le nostre forze, un settore difficile per il quale non è ammessa l’improvvisazione, ma serve la politica dei piccoli passi; siamo qui a dimostrare con i dati di questa edizione del 2019, che siamo stati seguiti con apprezzamento da un numero crescente di galleristi, di artisti, di appassionati cultori dell’arte. E possiamo anche dire, con un po’ di vanto, che negli anni abbiamo dato il nostro contributo di conoscenza per diffondere tra giovani e meno giovani l’amore per l’arte moderna: a volte snobbata, a volte non compresa, ma sempre motivo di dibattito e di curiosità. Un tentativo questo che da qualche tempo stiamo incentivando con l’apertura ai giovani artisti pro- ponendo anche un’arte accessibile a tutte le tasche: tanto che nei nostri spazi figurano, democraticamente fianco a fianco, opere da decine di migliaia di euro di valore ed altre che si fermano a poche centinaia di euro. Se abbiamo attraversato indenni il confine tra due secoli con le sue crisi, è per- ché l’arte è sì bene rifugio, ma sostanzialmente rappresenta il bello, dimostra che l’uomo è capace di grandi azzardi e di mettersi sempre in gioco sperimen- tando forme nuove di espressione; l’arte è tecnica e insieme fantasia, ovvero un connubio unico e per questo quasi magico tra terra e cielo. -

Documenta 8 (Küssende Fernseher) Von Ralph Hammerthaler

documenta 8 (Küssende Fernseher) von Ralph Hammerthaler Ende Oktober 1981 war das proT erstmals in einer großen Ausstellung zu sehen. Für ein Theater mag das ungewöhnlich erscheinen, nicht so aber für das proT, denn Sagerer fühlte sich bildenden Künstlern oft enger verbunden als Theatermachern. Schon sein früher Komplize von Hündeberg war Maler. Nikolai Nothof und Karl Aichinger, beide als Schauspieler im Ensemble, fingen in den 1970er Jahren an zu malen und stellten ihre Bilder im Kellertheater aus. Bei Aktionsabenden des proT lösten sich die Grenzen der Genres ohnehin auf. Dafür, dass sich die Kontakte zur Kunstszene vertieften, sorgte nun Brigitte Niklas. In der Künstlerwerkstatt Lothringer Straße 13 zeigten zwölf Münchner Künstler Videoinstallationen, darunter auch Barbara Hamann und Wolfgang Flatz. Die Installation des proT erwies sich als aufwändig, denn sie konnten nicht anders, als mit dem ganzen Theater anzurücken. Ihr Kunst-Video hing an der Produktion Münchner Volkstheater oder umgekehrt: Das Theater hing am Kunst-Video, umso mehr, als es davon seine Einsätze bezog. Wie oben erwähnt, führte bei diesem Stück das Video Regie. Im Gespräch mit dem Magazin Videokontakt antwortete Sagerer auf die Frage nach der Grenze zwischen den Genres: „Alles, was ich mache, fällt unter den Begriff ‚Theater‘. Das Theater ist die einzige unbegrenzte Kunst, vom Material her eigentlich überhaupt nicht definierbar. Alles, was unter dem Namen ‚Theater‘ passiert, wird Theater. Wenn man Film im Theater einsetzt, ist es kein Film mehr, sondern Theater. Wenn man Theater filmt, wird es immer ein Film. Die Erfahrung ‚Theater‘ kann der Film nicht vermitteln, während Film, Fernsehen und Musik Bestandteile der Erfahrung ‚Theater‘ sein können.“ Und befragt nach seinen Plänen mit Video im Theater, sagte er: „Wir wollen in Zukunft mehr Monitore einsetzen, die von jedem Punkt des Raums aus sichtbar sind. -

Note to the Secretary-General Tonight You and Mrs. Annan Have

Note to the Secretary-General Tonight you and Mrs. Annan have agreed to drop by (from 6:35-6:45 p.m.) the reception in the West Terrace hosted by Yoko Ono wherein she will present grants to an Israeli and a Palestinian artist in her own Middle East humanitarian arts initiative. When Mrs. Annan and you arrive David Finn, Philippa Polskin and Holly Peppe of Ruder-Finn, will greet you. You will then be accompanied into the center of the room where two easels will display the work of the two artist recipients of the LennonOno Grants, Khalil Rabah and Zvi Goldstein. The following people will greet you and stand with you for a brief photo-op: > Yoko Ono > Zvi Goldstein, Israeli artist, grant recipient > Khalil Rabah, Palestinian artist, grant recipient > Jack Persekian, Founder & Director, Anadiel Gallery, Jerusalem > Suzanne Landau, Chief Curator, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem > Shlomit Shaked, Independent Curator, Israel. At 6:45 p.m. you will proceed to the Macalester Reception and dinner, in Private Dining Room #8. Kevin S.: 9 October 2002 Copy to: Ms. S. Burnheim ROUTING SLIP FICHE DE TRANSMISSION TO: A A: OJ *Mt* FROM: / /" DE: /64< ^*^/^^~^ Room No. — No de bureau Extension — Poste Date / G&W aiLbfo^ FOR ACTION POUR SUITE A DONNER FOR APPROVAL POUR APPROBATION FOR SIGNATURE POUR SIGNATURE FOR COMMENTS POUR OBSERVATIONS MAY WE DISCUSS? POURRIONS-NOUS EN PARLER ? YOUR ATTENTION VOTRE ATTENTION AS DISCUSSED COMME CONVENU AS REQUESTED SUITE A VOTRE DEMANDS NOTE AND RETURN NOTER ET RETOURNER FOR INFORMATION POUR INFORMATION COM.6 12-78) ZVI GOLDSTEIN Artist Recipient of the LennonOno Grant for Peace Born in Transylvania, Romania in 1947, artist Zvi Goldstein immigrated to Israel in 1958. -

Open Windows 10

Open Windows 10 Resonance Chamber. Museum Folkwang and the Beginning of Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza’s German Expressionist Collection Nadine Engel Emil Nolde Young Couple, c. 1931–35 22 HollandischerDirektor bracht ✓ Thyssen-Schatzenach Essen Elnen kaum zu bezifiernden Wert bat elne Ausslellung des Folkwang-Museums, die btszum 20. Marz gezelgt wird: sie ent hiilt hundertzehn Melsterwerke der europaisdlen Malerei des 14. bis 18. Jahrhunderts aus der beriihmten Sammlung Sdtlo8 Roboncz, die heute Im Besitz des nodt Jungen Barons H. H. Thys sen-Bornemisza ist und in der Villa Favorlta bei Lugano ihr r Domlzil hat. Insgesamt mnfafll sie 350 Arbeiten. Erst um 1925 wurde sle in besdieidenen An fll.ngen von August Thyssen ge grilndet, dann von dessen SOh nen, zumal von Heinrkh Thys sen, entscheidend ausgebaut. Jetzt billet und vermehrt sie der Enke!. B~i d~r_ErOff11ungsfeicr,zu d~r auch l I ~~~~e~~l:~~n F~~~m~~!sr:::~ei:~ _,_,J NRW ersdli,:mcn war, -sagte Ober- - / ~~;~::~:ii5~c~dlNJ!:~n;(o~W~ti.~: Baron und ::;o;~~ lhJ,~~!~!~g~:::,~~~~::~o,::;~~:.;';~'::i~~=~Nie1wolldt ;~~~:::ig~\t~~~~"::::cann1~bt~~J st~Uung in der Bund~srepublik K{iln, nerer Tcil der Sammlung Thysscn- :U~~!~:~\:~s:J~;~n:,!%~'~!i~gd~::~ ~o~qs:~ldi~u~~Esj~~ i1~0;~~:~~:J1a~~; t:;ge 1~is~~~~~:_uE'!1::~dd!~tg:t:J:;; t~~}:~~:~ J1~!~1:~~::1gs;;;;:;n;u;::: ;;~~7i~gd~~S:s~~n ~zt:~:~ieiab:t ;ii~e~u;/~:?n_anredtnen, iwe1tep_~~~: komme, der eines solchen Ausgleidts lugano - Rotterdam - Essen I drin9en? bedarf. Baron_H. ~-1.Thyssen· So trafen denn die behutsamgepfleg Bornem!sza sdtl!derte in einer kuncn ten Schiille in drei wohlgesidierlen Relle die_ En\widdu~g Iler Sammlu~g Transporten die Fahrt von Rotterdam und erklarte dann die Ausstellung fur nadl Essen an, nadldem sie ein paar fig. -

Copyrighted Material

BLBK621-01 BLBK621-Green Printer: Yet to Come January 18, 2016 19:3 Trim: 229mm × 152mm Part 1 The Second Wave COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL 17 BLBK621-01 BLBK621-Green Printer: Yet to Come January 18, 2016 19:3 Trim: 229mm × 152mm Figure 1.1 City view, Kassel, during documenta, with at left the Museum Frideri- cianum, documenta’s main venue. Photograph Charles Green. 18 BLBK621-01 BLBK621-Green Printer: Yet to Come January 18, 2016 19:3 Trim: 229mm × 152mm 1 1972: The Rise of the Star-Curator Exhibitions in this chapter: documenta 5: Befragung der Realitat,¨ Bildwelten heute (documenta 5: Questioning reality, image worlds today) (1972, Kassel, Germany) Introduction The focus of this chapter is documenta5: Befragung der Realitat,¨ Bildwel- ten heute (Questioning reality: Image worlds today), the landmark 1972 edition of documenta. Founded in 1955 by veteran art historian Arnold Bode and now held every five years in the German city of Kassel, docu- menta was from the outset intended to be a survey exhibition of modern art. Although it initially played a secondary role to a monster-sized flower show in this small provincial city – located closer to the East German bor- der than to Cologne or Dusseldorf,¨ West Germany’s principal art centers – documenta is now widely regarded as the most important mega-exhibition of all.1 Inclusion in documenta is an even surer marker of an artist’s impor- tance than selection into Venice, Sao˜ Paulo, or any of the other biennials described in this book. documenta 5 was directed by the immensely influential Swiss curator Harald Szeemann. -

Catalogo 144 TENDENZE INFORMALI

COMUNE DI BRESCIA CIVICI MUSEI D’ARTE E STORIA PROVINCIA DI BRESCIA ASSOCIAZIONE ARTISTI BRESCIANI TENDENZE INFORMALI DAGLI ANNI CINQUANTA AI PRIMI ANNI classici del contemporaneo SETTANTA NELLE COLLEZIONI BRESCIANE mostra a cura di Alessandra Corna Pellegrini 144 aab - vicolo delle stelle 4 - brescia 22 settembre - 17 ottobre 2007 orario feriale e festivo 15.30 - 19.30 edizioni aab lunedì chiuso L’AAB è orgogliosa di inaugurare la stagione 2007/2008 con una prestigiosa esposizione, di rilievo certamente non solo locale, che propone opere di artisti fra i più rappresentativi dell’Informale. La mostra prosegue la fortunata serie “Classici del contemporaneo” dedicata al collezionismo della nostra provincia, che ha già proposto artisti come Kolàr, Demarco, Fontana, Munari, Birolli, Dorazio, Vedova, Fieschi, Adami, Baj ed esponenti della Nuova Figurazione. La curatrice della rassegna, la storica dell’arte Alessandra Corna Pellegrini, ha selezionato un nucleo essenziale di opere (34) che rappresentano esempi molto significativi dell’esperienza e del linguaggio di un movimento pur tanto complesso e così difficile da circoscrivere come l’Informale e dimostrano l’alta qualità delle collezioni bresciane, sia pubbliche sia private. L’impegno dell’AAB, scientifico organizzativo finanziario, può ben essere documentato dall’importanza internazionale degli autori proposti, da Dubuffet Mathieu Schneider a Afro Basaldella Corpora Dorazio Fontana Morlotti Santomaso Scanavino Scialoja Tancredi Turcato. L’esposizione, come è prassi costante dell’Associazione, -

Northern Gothic: Werner Haftmann's German

documenta studies #11 December 2020 NANNE BUURMAN Northern Gothic: Werner Haftmann’s German Lessons, or A Ghost (Hi)Story of Abstraction This essay by the documenta and exhibition scholar Nanne Buurman I See documenta: Curating the History of the Present, ed. by Nanne Buurman and Dorothee Richter, special traces the discursive tropes of nationalist art history in narratives on issue, OnCurating, no. 13 (June 2017). German pre- and postwar modernism. In Buurman’s “Ghost (Hi)Story of Abstraction” we encounter specters from the past who swept their connections to Nazism under the rug after 1945, but could not get rid of them. She shows how they haunt art history, theory, the German feuilleton, and even the critical German postwar literature. The editor of documenta studies, which we founded together with Carina Herring and Ina Wudtke in 2018, follows these ghosts from the history of German art and probes historical continuities across the decades flanking World War II, which she brings to the fore even where they still remain implicit. Buurman, who also coedited the volume documenta: Curating the History of the Present (2017),I thus uses her own contribution to documenta studies to call attention to the ongoing relevance of these historical issues for our contemporary practices. Let’s consider the Nazi exhibition of so-called Degenerate Art, presented in various German cities between 1937 and 1941, which is often regarded as documenta’s negative foil. To briefly recall the facts: The exhibition brought together more than 650 works by important artists of its time, with the sole aim of stigmatizing them and placing them in the context of the Nazis’ antisemitic racial ideology. -

Kuvakirjasto Nordstromin Kokoelma.Pdf

Lars-Gunnar Nordströmin kirjakokoelma Taideyliopiston kirjastossa / Lars-Gunnar Nordström's collection in the University of the Arts Helsinki Library Nimeke / Title Tekijä / Author Julkaisuvuosi / Publishing year Julkaisija / Publisher New York : Museum of Modern Art ; Picasso and Braque : pioneering cubism William Rubin 1989 Boston Richard Serra edited by Ernst-Gerhard Güse ; with contributions by Yves-Alain Bois ... [ja muita]. 1988 New York, N.Y. : Rizzoli Piet Mondrian : 1872-1944 Yve-Alain Bois, Joop Joosten, Angelica Zander Rudenstine, Hans Janssen. 1994 Boston : Little, Brown and Company Franciska Clausen. Bd. 2, I "de kolde skuldres land" 1932-1986 Finn Terman Frederiksen. 1988 Randers : Buch Salvador Dalí: rétrospective 1920-1980. Centre Georges Pompidou. 1980 Paris : Centre Georges Pompidou Russia: an architecture for world revolution / El Lissitzky ; translated by Eric Dluhosch Lissitzky, El 1970 London : |b Lund Humphries, |c 1970. Kandinsky François Le Targat 1986/1988 London : Academy Editions New York : Solomon R. Guggenheim Kandinsky at the Guggenheim Vivian Endicott Barnett 1983 Museum : Abbeville Press Varvara Stepanova : a constructivist life A. N. Lavreniev; John E. Bowlt 1988 London : Thames and Hudson P.O. Ultvedt : Tvivel och övermod : arbeten från 1945 till 1988 Per Olof Ultvedt; Malmökonsthall 1988 Malmö: Den konsthall Sonia Delaunay : fashion and fabrics Jacques Damase 1991 New York : H.N. Abrams Jackson Pollock Daniel Abadie; Claire Stoullig; Musée national d'art moderne (France) 1982 Paris : Centre Georges -

Conceptual Art: a Critical Anthology

Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology Alexander Alberro Blake Stimson, Editors The MIT Press conceptual art conceptual art: a critical anthology edited by alexander alberro and blake stimson the MIT press • cambridge, massachusetts • london, england ᭧1999 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval)without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Adobe Garamond and Trade Gothic by Graphic Composition, Inc. and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Conceptual art : a critical anthology / edited by Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-01173-5 (hc : alk. paper) 1. Conceptual art. I. Alberro, Alexander. II. Stimson, Blake. N6494.C63C597 1999 700—dc21 98-52388 CIP contents ILLUSTRATIONS xii PREFACE xiv Alexander Alberro, Reconsidering Conceptual Art, 1966–1977 xvi Blake Stimson, The Promise of Conceptual Art xxxviii I 1966–1967 Eduardo Costa, Rau´ l Escari, Roberto Jacoby, A Media Art (Manifesto) 2 Christine Kozlov, Compositions for Audio Structures 6 He´lio Oiticica, Position and Program 8 Sol LeWitt, Paragraphs on Conceptual Art 12 Sigmund Bode, Excerpt from Placement as Language (1928) 18 Mel Bochner, The Serial Attitude 22 Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier, Niele Toroni, Statement 28 Michel Claura, Buren, Mosset, Toroni or Anybody 30 Michael Baldwin, Remarks on Air-Conditioning: An Extravaganza of Blandness 32 Adrian Piper, A Defense of the “Conceptual” Process in Art 36 He´lio Oiticica, General Scheme of the New Objectivity 40 II 1968 Lucy R. -

Documenta VIII

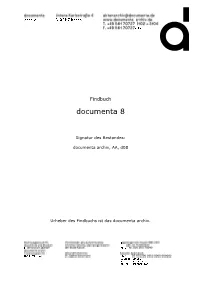

Findbuch documenta 8 Signatur des Bestandes: documenta archiv, AA, d08 Urheber des Findbuchs ist das documenta archiv. documenta archiv, AA, d08 Mappe 1 Presseausschnitte 1982 – 29.07.1986 Mappe 2 Presseausschnitte 22.08.1986 – 31.12.1986 Mappe 3 Presseausschnitte 01.01.1987 – 05.06.1987 Mappe 4 Presseausschnitte 06.06.1987 – 12.06.1987 Mappe 5 Presseausschnitte 13.06.1987 Mappe 6 Presseausschnitte 14.06.1987 – 30.06.1987 Mappe 7 Presseausschnitte 01.07.1987 – 14.07.1987 Mappe 8 Presseausschnitte 15.07.1987 – 31.07.1987 Mappe 9 Presseausschnitte 01.08.1987 – 31.08.1987 Mappe 10 Presseausschnitte 01.09.1987 – 30.09.1987 Mappe 11 Presseausschnitte ab 01.10.1987 Mappe 12 Presseausschnitte Ausland (alphabetisch geordnet nach Ländern) A – N Mappe 13 Presseausschnitte Ausland (alphabetisch geordnet nach Ländern) O – Z Mappe 14a Presseausschnitte zu Rahmenveranstaltungen 1986-1988 (thematisch geordnet) - Am Rande - Ecce Homo - etcetera Mappe 14b Presseausschnitte zu Rahmenveranstaltungen 1986-1988 (thematisch geordnet) - Gruppenkunstwerke - Kulturfabrik Salzmann - Kasseler Musiktage - Peter Rühmkorf „documenta-Schreiber“ - Theater Mappe 15 a Presseausschnitte Theater, Performance, Audiothek Mappe 15 b Liste Rundfunk und Fernsehbeiträge documenta archiv, AA, d08 Mappe 16 - Pressespiegel I + II (1986 – 05. 1987) - documenta-Pressestimmen “Ein Halbzeit-Service” Mappe 17 a verschiedene Pressespiegel Mappe 17 b verschiedene Pressespiegel Mappe 17 c verschiedene Pressespiegel Mappe 17 d Pressespiegel Ausland Mappe 18 a „Documenta press“ Information zur Documenta 8 Ausgaben: 0 (1986), 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 (1987) Mappe 18 b Zeitungen und Zeitschriften zur documenta 8 - PflasterStrand Nr. 264, 13.6.-26.6.1987 - Wolkenkratzer, Art Journal 4/87 (Juni/Juli/August) - Arte Nr. -

Editor's Note

Editor’s Note Dear readers, Although Bauhaus is relevant throughout history, this German school of art remains an open issue in art, architecture, design, and communication, addressing the following question: To what extent is Bauhaus even possible nowadays? Thus, this was our question for the Art Style Magazine's Bauhaus Special Edition. Therefore, in an attempt to showcase some of the most important issues so our readers can attain a broad notion of this German school's legacy, our Editorial Team has been working diligently and participated in several significant events, talks, round tables, and exhibitions. The opening festival and construction of the Bauhaus Museum in Weimar, for example, offered a great view of the importance of the Bauhaus. Above all, in the sense of arts and crafts in connection with industry, this school outlined a relationship of teaching design from product development, consumption to the changes of living together. Recently, the so-called "Fishfilet scandal" – an attempt to prevent a live event by a German rock band – was an important facet in the discussion that the Bauhaus still plays a significant role in the political scene. As artists and politicians said, the ban on concerts means a "terrifying history" for Bauhaus-Dessau. A month ago, we heard news from a round table, and artistic interventions under the title "How political is the Bauhaus?". These talks had taken place in the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (House of World Cultures) in Berlin on January 19, 2019. It was part of the opening festival of Bauhaus's centenary and supported by the Senate Department for Culture and Europe.