Documenta 11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D'art Ambition D'art Alighiero Boetti, Daniel Buren, Jordi Colomer, Tony

Ambition d’art AmbitionAlighiero Boetti, Daniel Buren, Jordi Colomer, Tony Cragg, Luciano Fabro, Yona Friedman, Anish Kapoor, On Kawara, Martha Rosler, Jeff Wall, Lawrence Weiner d’art16 May – 21 September 2008 The Institut d’art contemporain aspect (an anniversary) and the is celebrating its 30th anniversary setting – the inauguration of an in 2008 and on this occasion exhibition in the artistico-political has invited its founder, context of the 2000s – it is aimed Jean Louis Maubant, to design at shedding light on what the an exhibition, accompanied by an ‘ambition’ of art and its ‘world’ important publication. might be. The exhibition Ambition d’art, held in partnership with the The retrospective dimension Rhône-Alpes Regional Council of the event is presented above and the town of Villeurbanne, is a all in the two volumes (Alphabet strong and exceptional event for and Archive) of the publication to the Institute: beyond the anecdotal which it has given rise. Institut d’art contemporain, Villeurbanne www.i-art-c.org Any feedback in the exhibition is Yona Friedman, Jordi Colomer) or less to commemorate past history because they have hardly ever been than to give present and future shown (Martha Rosler, Alighiero history more density. In fact, many Boetti, Jeff Wall). Other works have of the works shown here have already been shown at the Institut never been seen before. and now gain fresh visibility as a result of their positioning in space and their artistic company (Luciano Fabro, Daniel Buren, Martha Rosler, Ambition d’art Tony Cragg, On Kawara). For the exhibition Ambition d’art, At the two ends of the generation Jean Louis Maubant has chosen chain, invitations have been eleven artists for the eleven rooms extended to both Jordi Colomer of the Institut d’art contemporain. -

Bernd & Hilla Becher Biography

P A U L A C O O P E R G A L L E R Y Bernd & Hilla Becher Biography Bernd Becher Born: Siegen, Germany 1931 Died: 2007 Hilla Becher Born: Potsdam, Germany 1934 Died: 2015 EDUCATION Bernd Becher 1976 Professor of photography at Staatlich Kunstakademie Düsseldorf 1972 Guest lecturer Hochschule für Bildende Künste, Hamburg 1957-1961 Studies in typography at Staatliche Kunstakademie Düsseldorf 1953-1956 Studies in lithography and painting at Staaliche Kunstakademie Stuttgart under Karl Rösing Hilla Becher 1972-1973 Guest Lecturer Hochschule für bildende Künste, Hamburg 1958-1961 Studies in photography at Kunstakademie Düsseldorf GRANTS & AWARDS 2014 Rheinischer Kulturpreis der Sparkassen-Kulturstiftung Rheinland 2002 The Erasmus Prize 1991 The Leon D’Oro award for sculpture at the Venice Biennale ONE-PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2019 “Bernd & Hilla Becher: Industrial Visions,” National Museum Cardiff, Wale, UK (10/26/19 – 3/1/20) “Bernd & Hilla Becher: 1962-2000,” PKM Gallery, Seoul, Korea “Bernd & Hilla Becher: Kohlebunker,” Kunstarchiv Kaiserwerth, Düsseldorf, Germany 2018 “Bernd & Hilla Becher,”Konrad Fischer Galerie, Berlin, Germany 2014 “Bernd & Hilla Becher,” Fotografien aus fünf Jahrzehnten, Konrad Fischer Galerie, Düsseldorf “Bernd & Hilla Becher,” Sprüth Magers, London 2013 “Photographische Sammlung der SK Stiftung Kultur, Cologne Dia Art Foundation, New York Siegerländer Fachwerkhäuser, Orts- und Dorfansichten des Siegerlandes, Siegerländer Gruben und Hütten, Holzfördertürme in Pennsylvania, Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Siegen 2012 galerija TR3, Ljubljana, Slowenia Coal Mines. Steel Mills., Galerie Rudolfinum, Prague Bernd and Hilla Becher, Sonnabend Gallery, New York Bernd & Hilla Becher. Imprimés 1964-2010, Grand Palais, Paris 2011 Bergwerke und Hütten, Industrielandschaften, Fotomuseum Winterthur 534 WEST 21ST STREET, NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10011 TELEPHONE 212.255.1105 FACSIMILE 212.255.5156 P A U L A C O O P E R G A L L E R Y Blick in die Sammlung: Bernd und Hilla Becher. -

Bernd & Hilla Becher Coal Mines. Steel Mills

Bernd & Hilla Becher: Coal Mines. Steel Mills. 22.3.2012 – 3.6.2012 This unique representative collection of 95 black-and-white photographs by Bernd and Hilla Becher focuses on so-called “Industrial Landscapes” – a term the artists themselves use to describe a particular type of image, which does not seek to portray individual works of architecture as such, but rather the situation of heavy industry plants within their urban and landscape context. The project Coal Mines. Steel Mills. is based on works created in the Ruhr Valley (Ruhrgebiet). From as far back as the early 1960s, the mining facilities and surrounding steel mills of the area have provided both artists with a major theme for their work, one they have followed to the most minute details in their records of entire industrial zones, such as the mines Hannover in Bochum, Zollern II in Dortmund, or Concordia in Oberhausen. Photographs from the Ruhr Valley are accompanied by images from the area around Siegen in North Rhine-Westphalia as well as from the UK, France and the United States in such a way – in keeping with the artists’ intent – as to draw comparison between the language of industrial architecture as it has evolved over the course of the previous century, regardless of regional or national borders. Bernd and Hilla Becher rank among the most prominent representatives of post-war German photography, not only due to their monumental oeuvre, but also the exceptional degree of international success of the various adherents of the Düsseldorf School of Photography, which they founded. As pioneers of conceptual photography, they directly influenced several generations of German photographers. -

November 23Rd, 2010 Gene Beery

Gene Beery at Algus Greenspon Within Gene Beery’s conceptual language-based paintings, there always seems to be some kind of joke—and not always one that the viewer is in on. Among the pieces included in the artist’s 50-year retrospective was Note (1970), in which the words “NOTE: MAKE A PAINTING OF A NOTE AS A PAINTING” are rendered in puffy, candy-colored letters on a pale background with a black framelike border. In another, the words “life without a sound sense of tra can seem like an incomprehensible nup” (1994) are written in black capital letters on white; the canvas is divided by a thick black line, which cuts through the lines of text so that the reversed words “art” and “pun” are separated from the rest. Gene Beery, Note, 1970, acrylic on canvas, 34 x 42 inches. The exhibition began with works from the late 1950s, when Beery, then employed as a guard at the Museum of Modern Art, was “discovered” by James Rosenquist and Sol LeWitt. An “artist’s artist,” he was championed by artists who were, and would remain, better known than he. After a 1963 show at Alexander Iolas Gallery in New York, Beery moved to the Sierra Nevada mountains, where he still lives. While other artists using text and numbers who emerged in the 1960s—Lawrence Weiner, Joseph Kosuth, On Kawara, for example—produced mostly cerebral works lacking evidence of the artist’s hand, Beery seemingly poked fun at the high Conceptualism of the day. He continued to make his uniquely homespun and humorously irreverent canvases, the rawness of their execution a throwback to the Abstract Expressionists. -

THE MEDIA of PHOTOGRAPHY Special Issue of the Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism

CALL FOR PAPERS THE MEDIA OF PHOTOGRAPHY Special Issue of the Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism GUEST EDITORS Diarmuid Costello (University of Warwick) Dominic McIver Lopes (University of British Columbia) Three overlapping events occasion this proposal for a special issue of JAAC on the philosophy of photography. First, photography has matured as a visual art medium. No longer confined to specialist galleries, distribution networks, discourses, or educational programs, it has won mainstream institutional recognition – fine art museums increasingly mount major retrospectives of contemporary photographers’ work, and many of those museums now appoint curators of photography. Second, the boundary between photographic and non-photographic visual art has blurred, as lens-based technologies have found a home in a wide range of art practices from painting and theater through sculptural installation to conceptual art. Photography has become one more means at artists’ disposal; it is no longer just for photographers. Third, the rapid, ongoing development of digital imaging technologies is profoundly reshaping how photographs are made and displayed, and hence appreciated, while at the same time creating new venues for displaying photographs outside traditional art institutions. Taken together this conjunction of events raises fundamental philosophical questions about photography as an art and an aesthetic phenomenon. The proposed special issue is intended to address these questions by bringing them under a unifying theme, “the media of photography.” -

Northern Gothic: Werner Haftmann's German

documenta studies #11 December 2020 NANNE BUURMAN Northern Gothic: Werner Haftmann’s German Lessons, or A Ghost (Hi)Story of Abstraction This essay by the documenta and exhibition scholar Nanne Buurman I See documenta: Curating the History of the Present, ed. by Nanne Buurman and Dorothee Richter, special traces the discursive tropes of nationalist art history in narratives on issue, OnCurating, no. 13 (June 2017). German pre- and postwar modernism. In Buurman’s “Ghost (Hi)Story of Abstraction” we encounter specters from the past who swept their connections to Nazism under the rug after 1945, but could not get rid of them. She shows how they haunt art history, theory, the German feuilleton, and even the critical German postwar literature. The editor of documenta studies, which we founded together with Carina Herring and Ina Wudtke in 2018, follows these ghosts from the history of German art and probes historical continuities across the decades flanking World War II, which she brings to the fore even where they still remain implicit. Buurman, who also coedited the volume documenta: Curating the History of the Present (2017),I thus uses her own contribution to documenta studies to call attention to the ongoing relevance of these historical issues for our contemporary practices. Let’s consider the Nazi exhibition of so-called Degenerate Art, presented in various German cities between 1937 and 1941, which is often regarded as documenta’s negative foil. To briefly recall the facts: The exhibition brought together more than 650 works by important artists of its time, with the sole aim of stigmatizing them and placing them in the context of the Nazis’ antisemitic racial ideology. -

Welcome to A' Level Photography

Welcome to A’ level Photography • Now that you have decided to study A Level Photography, you will need to do a bit of preparation. This document contains information regarding the course structure, the summer project and some Photographers you should know to prepare you to start your A level in September. The purpose of studying Photography at A Level is to develop knowledge and understanding of: • Specialist vocabulary and terminology when analysing or explaining your own and others’ work • Theoretical research of a particular genre style and/or tradition • In‐depth understanding of a variety of media, techniques, and processes • Development of an idea, concept, or issue • Recording ideas and observations related to chosen lines of enquiry • Communicating a particular meaning, message, idea or feeling • There will be a pack to buy from school which will contain a selection of the and materials you will need. The cost of the pack will be approximately £50 What do I have to do in A Level Art? Photography? There are two components of the course‐ the personal investigation and the externally set assignment. The table below summarises the evidence you will produce for each component: A Level Components What will I need to do? How will I evidence this? Personal Investigation ‐Write a personal study (essay) ‐A 1000‐3000 word essay (coursework) based on your chosen theme ‐Research on a range of artists ‐Create a body of work related to and/or designers 60% a chosen theme/s ‐Exploration of a variety of ‐Create a final piece/s media, techniques and processes ‐Development of ideas in response to chosen artist/s/theme ‐Recording of ideas and observations Externally Set Assignment ‐Create preparatory studies ‐By creating a body of work (Exam) based on the theme based on the theme given. -

Download Transcript (PDF)

KAWARA: EXHIBITION OVERVIEW Jeffrey Weiss: On Kawara was a key figure in the art of the 1960s in particular. He began working in Japan and continued work in many other cities, finally settling in New York in the mid-’60s, where he was part of the community of Conceptual art during that period of time. He knew a lot of artists that we associate with Conceptualism including Sol LeWitt and Hanne Darboven, Joseph Kosuth and Dan Graham. It’s easy to associate his work, then, with the rise of Conceptualism, although Kawara’s work, when you examine it closely, stands well apart. This exhibition was organized in cooperation with the artist. And I really wanted to show every category of Kawara’s production since around 1964. We don’t call it a retrospective because Kawara’s work is based on time, on the passage of time. So the idea of the retrospective actually doesn’t apply in the conventional sense. Anne Wheeler: We heard from a number of his friends and colleagues from even years ago that it had always been his dream to have a show at the Guggenheim because of the cyclical nature of time and the way that the building represents that in the way that you can move throughout the chronology of his work. In organizing the show we are moving more or less chronologically through the series of his works, starting in the High Gallery with works from 1963 to ’65. Jeffrey Weiss: We’re also showing Paris–New York Drawings, which he produced in Paris and New York, where he was living—both places. -

New York Times July 15, 2003 'Critic's Notebook: for London, a Summer

New York Times July 15, 2003 ‘Critic's Notebook: For London, a Summer of Photographic Memory; Around the City, Images From Around the World’ Michael Kimmelman This city is immersed in photography exhibitions, a coincidence of scheduling, perhaps, that the museums here decided made a catchy marketing scheme. Posters and flyers advertise the “Summer of Photography.” Why not? I stopped here on the way home from the Venice Biennale, after which any exhibition that did not involve watching hours of videos in plywood sweatboxes seemed like a joy. The London shows leave you with no specific definition of what photography is now, except that it is, fruitfully, many things at once, which is a functionally vague description of the medium. You can nevertheless get a fairly clear idea of the differences between a good photograph and a bad one. In the first category are two unlike Americans: Philip-Lorca diCorcia, with a show at Whitechapel, and Cindy Sherman, at Serpentine. Into the second category falls Wolfgang Tillmans, the chic German-born, London-based photographer, who has an exhibition at Tate Britain that cheerfully disregards the idea that there might even be a difference between Categories 1 and 2. There is also the posthumous retrospective, long overdue, of Guy Bourdin, the high- concept soft-core-pornography fashion photographer for French Vogue and Charles Jourdan shoes in the 1970's and 80's, at the Victoria and Albert. And as the unofficial anchor for it all Tate Modern, which until now had apparently never organized a major photography show, has tried in one fell swoop to make up for lost time with “Cruel and Tender: The Real in the 20th Century Photograph.” The title is from Lincoln Kirstein's apt description of Walker Evans's work as “tender cruelty.” Like Tate Modern in general, “Cruel and Tender” is vast, not particularly logical and blithely skewed. -

Photographs Gathered by William T. Hillman

PRESS RELEASE | NEW YORK | 9 MARCH 2015 | FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CHRISTIE’S PRESENTS LEAVES OF LIGHT AND SHADOW: PHOTOGRAPHS GATHERED BY WILLIAM T. HILLMAN FREDERICK SOMMER, Livia, 1948. gelatin silver print, $80,000 - 120,000 RINEKE DIJKSTRA, Nicky, The Krazyhouse, Liverpool, England, January 19, 2009, $15,000 - 25,000 New York – On March 31, Christie’s will present the sale of Leaves Of Light And Shadow: Photographs Gathered By William T. Hillman, comprising 117 works judiciously acquired by William Hillman over the past three decades. With a sophisticated eye and tremendous dedication to photography, Mr. Hillman has built a comprehensive collection by pursuing consummate examples from top photographers spanning the history of the medium. In Hillman’s dedication to both photography and his hometown of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, his primary mission over the past three decades has been to build a world-class collection that will ultimately be gifted to the Carnegie Museum of Art. “There are gaps in the vintage acquisitions and the need to support and strengthen the contemporary component of this endeavor,” Mr. Hillman has stated. Hillman personally designated each work being presented for sale, and will reinvest the funds raised by the auction back into his mission. The top lot of the auction is Waitress in a Nudist Camp, N.J., 1963 by Diane Arbus (estimate: $200,000-300,000). Additional Highlights include: HENRI CARTIER-BRESSON, Piazza della Signoria, Florence, Italy, 1933, gelatin silver print | Estimate: $100,000-150,000 Piazza della Signoria, Florence was one of Henri Cartier Bresson's favorite images. He included it in his first solo exhibition in 1933 and his last retrospective in 2003, as well as in his first monograph The Decisive Moment in 1952, and his last monograph in 2005. -

Editor's Note

Editor’s Note Dear readers, Although Bauhaus is relevant throughout history, this German school of art remains an open issue in art, architecture, design, and communication, addressing the following question: To what extent is Bauhaus even possible nowadays? Thus, this was our question for the Art Style Magazine's Bauhaus Special Edition. Therefore, in an attempt to showcase some of the most important issues so our readers can attain a broad notion of this German school's legacy, our Editorial Team has been working diligently and participated in several significant events, talks, round tables, and exhibitions. The opening festival and construction of the Bauhaus Museum in Weimar, for example, offered a great view of the importance of the Bauhaus. Above all, in the sense of arts and crafts in connection with industry, this school outlined a relationship of teaching design from product development, consumption to the changes of living together. Recently, the so-called "Fishfilet scandal" – an attempt to prevent a live event by a German rock band – was an important facet in the discussion that the Bauhaus still plays a significant role in the political scene. As artists and politicians said, the ban on concerts means a "terrifying history" for Bauhaus-Dessau. A month ago, we heard news from a round table, and artistic interventions under the title "How political is the Bauhaus?". These talks had taken place in the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (House of World Cultures) in Berlin on January 19, 2019. It was part of the opening festival of Bauhaus's centenary and supported by the Senate Department for Culture and Europe. -

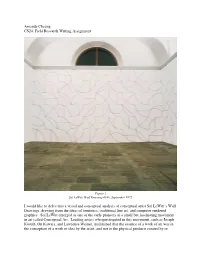

Sol Lewitt's Wall Drawings

Amanda Cheung CS24: Field Research Writing Assignment Figure 1 Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing #146, September 1972 I would like to delve into a visual and conceptual analysis of conceptual artist Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawings, drawing from the ideas of semiotics, traditional fine art, and computer rendered graphics. Sol LeWitt emerged as one of the early pioneers of a small but fascinating movement in art called Conceptual Art. Leading artists who participated in this movement, such as Joseph Kosuth, On Kawara, and Lawrence Weiner, maintained that the essence of a work of art was in the conception of a work or idea by the artist, and not in the physical products created by or representing the idea. For example, in Joseph Kosuth’s “One and Three Chairs,” the artwork is the idea of the chair, represented the word “chair,” a photograph of a chair, and the dictionary definition of chair. The work explores of the idea of the signifier, signified, and referent as studied in semiotics, and questions the role of the artist in creating a work; can he simply conceive an idea and let it be art, aside from any physical product? In Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawings, such as the one pictured in Figure 1, the essence of the work lay in the conception of the specific lines/shapes to be drawn on a wall, and not in the final product. LeWitt’s process involved conceiving the idea for the specific wall drawing and giving instructions to workers who executed the drawings in the exhibition spaces. Thus, a single “Wall Drawing” work would appear differently in different exhibitions because it would be executed by different people and in different spaces.