Sol Lewitt's Wall Drawings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D'art Ambition D'art Alighiero Boetti, Daniel Buren, Jordi Colomer, Tony

Ambition d’art AmbitionAlighiero Boetti, Daniel Buren, Jordi Colomer, Tony Cragg, Luciano Fabro, Yona Friedman, Anish Kapoor, On Kawara, Martha Rosler, Jeff Wall, Lawrence Weiner d’art16 May – 21 September 2008 The Institut d’art contemporain aspect (an anniversary) and the is celebrating its 30th anniversary setting – the inauguration of an in 2008 and on this occasion exhibition in the artistico-political has invited its founder, context of the 2000s – it is aimed Jean Louis Maubant, to design at shedding light on what the an exhibition, accompanied by an ‘ambition’ of art and its ‘world’ important publication. might be. The exhibition Ambition d’art, held in partnership with the The retrospective dimension Rhône-Alpes Regional Council of the event is presented above and the town of Villeurbanne, is a all in the two volumes (Alphabet strong and exceptional event for and Archive) of the publication to the Institute: beyond the anecdotal which it has given rise. Institut d’art contemporain, Villeurbanne www.i-art-c.org Any feedback in the exhibition is Yona Friedman, Jordi Colomer) or less to commemorate past history because they have hardly ever been than to give present and future shown (Martha Rosler, Alighiero history more density. In fact, many Boetti, Jeff Wall). Other works have of the works shown here have already been shown at the Institut never been seen before. and now gain fresh visibility as a result of their positioning in space and their artistic company (Luciano Fabro, Daniel Buren, Martha Rosler, Ambition d’art Tony Cragg, On Kawara). For the exhibition Ambition d’art, At the two ends of the generation Jean Louis Maubant has chosen chain, invitations have been eleven artists for the eleven rooms extended to both Jordi Colomer of the Institut d’art contemporain. -

November 23Rd, 2010 Gene Beery

Gene Beery at Algus Greenspon Within Gene Beery’s conceptual language-based paintings, there always seems to be some kind of joke—and not always one that the viewer is in on. Among the pieces included in the artist’s 50-year retrospective was Note (1970), in which the words “NOTE: MAKE A PAINTING OF A NOTE AS A PAINTING” are rendered in puffy, candy-colored letters on a pale background with a black framelike border. In another, the words “life without a sound sense of tra can seem like an incomprehensible nup” (1994) are written in black capital letters on white; the canvas is divided by a thick black line, which cuts through the lines of text so that the reversed words “art” and “pun” are separated from the rest. Gene Beery, Note, 1970, acrylic on canvas, 34 x 42 inches. The exhibition began with works from the late 1950s, when Beery, then employed as a guard at the Museum of Modern Art, was “discovered” by James Rosenquist and Sol LeWitt. An “artist’s artist,” he was championed by artists who were, and would remain, better known than he. After a 1963 show at Alexander Iolas Gallery in New York, Beery moved to the Sierra Nevada mountains, where he still lives. While other artists using text and numbers who emerged in the 1960s—Lawrence Weiner, Joseph Kosuth, On Kawara, for example—produced mostly cerebral works lacking evidence of the artist’s hand, Beery seemingly poked fun at the high Conceptualism of the day. He continued to make his uniquely homespun and humorously irreverent canvases, the rawness of their execution a throwback to the Abstract Expressionists. -

Download Transcript (PDF)

KAWARA: EXHIBITION OVERVIEW Jeffrey Weiss: On Kawara was a key figure in the art of the 1960s in particular. He began working in Japan and continued work in many other cities, finally settling in New York in the mid-’60s, where he was part of the community of Conceptual art during that period of time. He knew a lot of artists that we associate with Conceptualism including Sol LeWitt and Hanne Darboven, Joseph Kosuth and Dan Graham. It’s easy to associate his work, then, with the rise of Conceptualism, although Kawara’s work, when you examine it closely, stands well apart. This exhibition was organized in cooperation with the artist. And I really wanted to show every category of Kawara’s production since around 1964. We don’t call it a retrospective because Kawara’s work is based on time, on the passage of time. So the idea of the retrospective actually doesn’t apply in the conventional sense. Anne Wheeler: We heard from a number of his friends and colleagues from even years ago that it had always been his dream to have a show at the Guggenheim because of the cyclical nature of time and the way that the building represents that in the way that you can move throughout the chronology of his work. In organizing the show we are moving more or less chronologically through the series of his works, starting in the High Gallery with works from 1963 to ’65. Jeffrey Weiss: We’re also showing Paris–New York Drawings, which he produced in Paris and New York, where he was living—both places. -

Documenta 11

1/21/2015 Frieze Magazine | Archive | Documenta 11 Documenta 11 About this article Documenta 11 Published on 09/09/02 By Thomas McEvilley Each of artistic director Okwui Enwezor’s six co-curators - Sarat Maharaj, Octavio Zaya, Carlos Basualdo, Ute Meta Bauer, Susanne Ghez and Mark Nash - spoke briefly, followed by Enwezor himself. Maharaj identified the point of art today as ‘knowledge production’ and the point of this exhibition as ‘thinking the other’; Nash declared that the exhibition aimed to explore ‘issues of dislocation and migration’ (‘We’re all becoming transnational subjects’, he observed); Ghez stressed the unusual fact that as many as 70% of the works in the show were made explicitly for the Back to the main site occasion; Basualdo spoke of ‘establishing a new geography, or topology, of culture’; and Bauer spoke of ‘deterritorialization’. Finally, Enwezor began his reflections by referring to Chinua Achebe’s classic novel of pre-colonial Africa Things Fall Apart (1958). He spoke of the emergence of post-colonial identity, and said that he and his colleagues had aimed at something much larger than an art exhibition: they were seeking to find out what comes after imperialism. These remarks were significant because Documenta, along with the Venice Biennale, is one of the foremost venues at which the current cultural politics of the art world is laid out. In a sense the agenda proclaimed by these curators gave one a sense of déjà vu; or rather, it seemed not exactly to usher in a new era but to set a seal on an era first announced long ago. -

On Kawara Unanswered Questions Personal Structures Art Projects # 04 on Kawara

ON KAWARA UNANSWERED QUESTIONS Personal Structures Art Projects # 04 ON KAWARA ON KAWARA UNANSWERED QUESTIONS UNANSWERED QUESTIONS This book is the documentation of Personal Structures Art Projects #04. It has been published as a limited edition. The edition comprises 250 copies of which 50 DeLuxe, numbered from 1 to 50, and 50 DeLuxe hors commerce, numbered from I to L. The 150 Standard copies are numbered from 51 to 200. Each item of this limited edition consists of a book and a CD in a case, housed together in a cassette. The DeLuxe edition additionally contains a postcard with a question for On Kawara, returned to sender. This limited edition has been divided as follows: # 1-50: DeLuxe edition: Luïscius Antiquarian Booksellers, Netherlands # 51-200: Standard edition: Luïscius Antiquarian Booksellers, Netherlands HC I-L: Not for trade © 2009-2011. Text by Karlyn De Jongh © 2007-2009. Questions by the authors All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechan- ical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without permission of the editor. Concept by Rene Rietmeyer and Sarah Gold Design by Karlyn De Jongh Printed and bound under the direction of Andreas Krüger, Germany Production in coöperation with Christien Bakx, www.luiscius.com Published by GlobalArtAffairs Foundation, www.globalartaffairs.org KARLYN DE JONGH ON Kawara: UNANSWERED QUESTIONS Today is Saturday, 19 December 2009, and right now I am in my apart- ment in Venice, Italy. My name is Karlyn De Jongh. I am an indepen- dent curator and author from the Netherlands and I have spent two years working on the project Unanswered Questions to On Kawara. -

Georges Perec and on Kawara: Endotic Extravagance in Literature, Art, and Dance Leslie Satin New York University ______

Satin: Endotic Extravagance 50 Georges Perec and On Kawara: Endotic Extravagance in Literature, Art, and Dance Leslie Satin New York University _____________________________________ Abstract: This article analyzes the work of Georges Perec and On Kawara, two artists who have radically recast our understanding of space and time in literature and the visual arts, through the lens of the author’s post-modern dance practice and scholarship. Both artists, deeply affected by the chaos of World War II, began working in the mid- twentieth century: experimental author Georges Perec (1936-1983), known for his affiliation with OuLiPo (Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle, or Workshop for Potential Literature), the organization founded in 1960 to ratchet up the possibilities for conceiving and creating utterly new, or ‘potential’, literature, and On Kawara (1932- 2014), the Conceptual artist known for his large-scale recasting of personal and historical time, and his conversion of ‘private life’ into vast archives of documentary recording. The article looks both at spatial elements in the work of these artists, and at spatialized responses to their words and objects. It investigates Perec’s and Kawara’s divergent ideas of the everyday, as articulated through their practices—particularly their commitment to compositional scores and games exemplifying the ludic, and their insistence on the importance of seeing and noticing—and the implications of those practices, and the work they produced, regarding facticity, embodiment, self-representation, transformation, and, above all, the ongoing articulation of space and, by extension, time. Informed by work in human geography; affect, literary, and performance theory; and phenomenology, and by the writer’s experience in dance as a practice and area of scholarship, the article links these practices and ideas to those of post-modern dance to explore the fluid relationships among space, movement, bodies, and objects. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

FROM SERIAL DEATH TO PROCEDURAL LOVE: A STUDY OF SERIAL CULTURE By STEPHANIE BOLUK A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Stephanie Boluk 2 For my mum 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS One of the reasons I chose to come to the University of Florida was because of the warmth and collegiality I witnessed the first time I visited the campus. I am grateful to have been a member of such supportive English department. A huge debt of gratitude is owed to my brilliant advisor Terry Harpold and rest of my wonderful committee, Donald Ault, Jack Stenner, and Phil Wegner. To all of my committee: a heartfelt thank you. I would also like to thank all the members of Imagetext, Graduate Assistants United, and Digital Assembly (and its predecessor Game Studies) for many years of friendship, fun, and collaboration. To my friends and family, Jean Boluk, Dan Svatek, and the entire LeMieux clan: Patrick, Steve, Jake, Eileen, and Vince, I would not have finished without their infinite love, support, patience (and proofreading). 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.................................................................................................. 4 LIST OF FIGURES.......................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................... 11 Serial Ancestors..................................................................................................... -

On Kawara—Silence Is the First Full Representation of on Kawara’S Oeuvre, Including Every Category of Work He Created Between 1963 and 2013

FEBRUARY 6–MAY 3, 2015 Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Teacher Resource Unit A NOTE TO TEACHERS Organized with the cooperation of the artist, On Kawara—Silence is the first full representation of On Kawara’s oeuvre, including every category of work he created between 1963 and 2013. Much of it produced during his travels across the globe, Kawara’s work explores a personal and historical understanding of place and time. Kawara made his daily life and routines the focus of his work, including Date Paintings (the Today series); postcards (the I Got Up series); telegrams (the I Am Still Alive series); maps (the I Went series); lists of names (the I Met series); newspaper cuttings (the I Read series); the inventory of paintings (Journals); and calendars (One Hundred Years Calendars and One Million Years). Throughout the course of the exhibition, a live reading of One Million Years will be performed three days per week on the ground floor of the Guggenheim rotunda. On Kawara’s paintings were first shown at the Guggenheim Museum in the 1971Guggenheim International Exhibition. More than forty years later, this exhibition transforms the Frank Lloyd Wright–designed rotunda—itself a form that signifies movement through time and space—into a site where audiences can reflect on the cumulative power and depth of Kawara’s artistic practice. This Resource Unit focuses on various aspects of Kawara’s work and provides techniques for exploring both the visual arts and other areas of the curriculum. This guide is also available online at guggenheim.org/artscurriculum with images that can be downloaded or projected for classroom use. -

On Kawara 29,771 Days

This document was updated February 26, 2021. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. On Kawara 29,771 days SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 On Kawara and the Grande Complication, Mathematisch-Physikalischer Salon, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden 2019 On Kawara, David Lamelas, Jan Mot Gallery, Brussels [two-person exhibition] 2018 On Kawara, Krakow Witkin Gallery, Boston On Kawara: One Million Years (Reading), Museum MACAN, Jakarta, Indonesia 2017 On Kawara: One Million Years, Oratorio di San Ludovico Dorsoduro, Venice [organized by Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, England as part of 57th Venice Biennale] 2015 On Kawara: 1966, Museum Dhondt-Dhaenens, Deurle, Belgium [catalogue] On Kawara: One Million Years, Asia House, London On Kawara—Silence, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York [catalogue] 2013 On Kawara: One Million Years, BOZAR - Centre for Fine Arts, Brussels 2012 On Kawara: Date Painting(s) in New York and 136 Other Cities, David Zwirner, New York [catalogue] On Kawara - Lived Time, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam On Kawara: One Million Years, BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, England On Kawara: One Million Years, Jardin des Plantes, Paris 2010 On Kawara: Pure Consciousness at 19 Kindergartens, Walter and McBean Galleries, San Francisco Art Institute 2009 On Kawara: One Million Years, David Zwirner, New York 2008 On Kawara: 10 Tableaux and 16,952 Pages, Dallas Museum of Art [catalogue] 2007 On Kawara, Michèle Didier at Christophe Daviet-Théry, Paris 2006 Eternal -

The Date Paintings of on Kawara Author(S): Anne Rorimer Source: Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, Vol

The Art Institute of Chicago The Date Paintings of On Kawara Author(s): Anne Rorimer Source: Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, Vol. 17, No. 2 (1991), pp. 120-137+179-180 Published by: The Art Institute of Chicago Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4101587 . Accessed: 06/02/2014 16:24 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Art Institute of Chicago is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 198.40.29.65 on Thu, 6 Feb 2014 16:24:04 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions The Date Paintings of On Kawara ANNERORIMER Chicago I havekeenly experienced consciousness of myself today, at 81years, exactly as I was consciousof myselfat f or 6years.Consciousness is motionless. And it is onlybecause of its motionlessnessthat we are ableto see themotion of thatwhich we call time.If time passes,it is necessarythat thereshould be somethingwhich remains static. And it is consciousnessof self which is static LEOTOLSTOI (191o) Everylife is manydays, day after day. Wewalk throughourselves meeting robbers, ghosts,giants, old men, young men, wives, widows, brothers-in-love, but always meeting ourselves. -

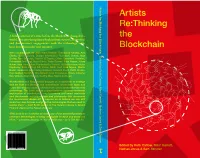

Artists Re:Thinking the Blockchain Artists Artists Re:Thinking

Artists Re:Thinking the Blockchain Artists Re:Thinking A future-artefact of a time before the blockchain changed the the world. This interdisciplinary book includes artistic, theoretical and documentary engagements with the technology some have described as the new internet. Blockchain With contributions by Jaya Klara Brekke, Theodoros Chiotis, Ami Clarke, Simon Denny, Design Informatics Research Centre, Max Mar Edited by Ruth Catlow, Dovey, Mat Dryhurst, Rachel O’Dwyer, César Escudero Andaluz, Primavera De Filippi, Rory Gianni, Peter Gomes, Elias Haase, Juhee Hahm, Max Hampshire, Kimberley ter Heerdt, Holly Herndon, Helen Kaplinsky, Paul Kolling, Elli Kuruş, Nikki Loef, Rob Myers, Martín Nadal, Noemata (Bjørn Magnhildøen), Edward Picot, PWR Studio, Paul Seidler, Surfatial, Hito Steyerl, Lina Theodorou, Pablo Velasco, Ben Vickers, Mark Waugh, Cecilia Wee, Martin Zeilinger. ‘Furtherfield and Torque have brought us a collection of writings and art that cut through the mainstream blockchain hype and reveal the diverse creative visions that can be embedded into the technology. The book strikes a great balance between technical Nathan Jones & Sam Skinner c Garrett, explanation of blockchains, cryptocurrency and smart contracts and the broader politics, culture and philosophy that surrounds the innovations. Above all, it inspires us to believe we can still invent our own futures and grow the technologies that we need to realise them.’ – Brett Scott, author of The Heretic’s Guide to Global Finance: Hacking the Future of Money ‘This book is on -

Dan Graham Transcript

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART ORAL HISTORY PROGRAM INTERVIEW WITH: DAN GRAHAM, Artist INTERVIEWER: SABINE BREITWIESER, MoMA Chief Curator of Media and Performance Art LOCATION: THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART DATE: NOVEMBER 1, 2011 TRANSCRIBER: Janet Crowley, Transcription Completed November 15, 2011 [Crew Discussion] SB: Hi, Dan, hello. I was asked to say the day of today. It’s November the first, 2011, and we are at The Museum of Modern Art on 11 West 53rd Street at the Drawing Study Center. I am Sabine Breitweiser, Chief Curator of Media and Performance Art, talking to artist Dan Graham. Do you want to introduce yourself? DG: Yes. I actually think of myself as more of a writer than an artist, and I don’t think of myself as an architect, but my work is always a hybrid. So I began with magazines, magazine articles and pages. SB: Okay, Dan. You usually start a conversation talking about someone’s zodiac, so I thought that might be a good point to start today. [0:05:17] DG: That’s for picking up women. [laughter] SB: That’s for picking up women, so pick me up. [laughing] So, you’re an Aries, and you recently sent me your zodiac description where you introduced yourself as being a pioneer, re-inventing, constantly yourself. DG: Well, I wouldn’t say that. I would just say that I admire, among the politicians, Kruschev, who was an Aries, who de-Stalinized Russia. And also his son is a very famous American computer scientist. But in terms of the zodiac, my birthday is MoMA Archives Oral History: D.