François Morellet/Sol Lewitt: a Case Study Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copertina Artepd.Cdr

Trent’anni di chiavi di lettura Siamo arrivati ai trent’anni, quindi siamo in quell’età in cui ci sentiamo maturi senza esserlo del tutto e abbiamo tantissime energie da spendere per il futuro. Sono energie positive, che vengono dal sostegno e dal riconoscimento che il cammino fin qui percorso per far crescere ArtePadova da quella piccola edizio- ne inaugurale del 1990, ci sta portando nella giusta direzione. Siamo qui a rap- presentare in campo nazionale, al meglio per le nostre forze, un settore difficile per il quale non è ammessa l’improvvisazione, ma serve la politica dei piccoli passi; siamo qui a dimostrare con i dati di questa edizione del 2019, che siamo stati seguiti con apprezzamento da un numero crescente di galleristi, di artisti, di appassionati cultori dell’arte. E possiamo anche dire, con un po’ di vanto, che negli anni abbiamo dato il nostro contributo di conoscenza per diffondere tra giovani e meno giovani l’amore per l’arte moderna: a volte snobbata, a volte non compresa, ma sempre motivo di dibattito e di curiosità. Un tentativo questo che da qualche tempo stiamo incentivando con l’apertura ai giovani artisti pro- ponendo anche un’arte accessibile a tutte le tasche: tanto che nei nostri spazi figurano, democraticamente fianco a fianco, opere da decine di migliaia di euro di valore ed altre che si fermano a poche centinaia di euro. Se abbiamo attraversato indenni il confine tra due secoli con le sue crisi, è per- ché l’arte è sì bene rifugio, ma sostanzialmente rappresenta il bello, dimostra che l’uomo è capace di grandi azzardi e di mettersi sempre in gioco sperimen- tando forme nuove di espressione; l’arte è tecnica e insieme fantasia, ovvero un connubio unico e per questo quasi magico tra terra e cielo. -

D'art Ambition D'art Alighiero Boetti, Daniel Buren, Jordi Colomer, Tony

Ambition d’art AmbitionAlighiero Boetti, Daniel Buren, Jordi Colomer, Tony Cragg, Luciano Fabro, Yona Friedman, Anish Kapoor, On Kawara, Martha Rosler, Jeff Wall, Lawrence Weiner d’art16 May – 21 September 2008 The Institut d’art contemporain aspect (an anniversary) and the is celebrating its 30th anniversary setting – the inauguration of an in 2008 and on this occasion exhibition in the artistico-political has invited its founder, context of the 2000s – it is aimed Jean Louis Maubant, to design at shedding light on what the an exhibition, accompanied by an ‘ambition’ of art and its ‘world’ important publication. might be. The exhibition Ambition d’art, held in partnership with the The retrospective dimension Rhône-Alpes Regional Council of the event is presented above and the town of Villeurbanne, is a all in the two volumes (Alphabet strong and exceptional event for and Archive) of the publication to the Institute: beyond the anecdotal which it has given rise. Institut d’art contemporain, Villeurbanne www.i-art-c.org Any feedback in the exhibition is Yona Friedman, Jordi Colomer) or less to commemorate past history because they have hardly ever been than to give present and future shown (Martha Rosler, Alighiero history more density. In fact, many Boetti, Jeff Wall). Other works have of the works shown here have already been shown at the Institut never been seen before. and now gain fresh visibility as a result of their positioning in space and their artistic company (Luciano Fabro, Daniel Buren, Martha Rosler, Ambition d’art Tony Cragg, On Kawara). For the exhibition Ambition d’art, At the two ends of the generation Jean Louis Maubant has chosen chain, invitations have been eleven artists for the eleven rooms extended to both Jordi Colomer of the Institut d’art contemporain. -

Utilizing Adobe Illustrator's Blend and Transform in Designing Op-Art Items

Arts and Design Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-6061 (Paper) ISSN 2225-059X (Online) Vol.44, 2016 Utilizing Adobe Illustrator's Blend and Transform in Designing Op-Art Items Randa Darwish Mohamed Assistant Professor in Printing, Publishing and Packaging Dept., Faculty of Applied Arts, Helwan University, Egypt. Abstract Op-Art can strengthen the product image and can combine culture elements which satisfies consumers’ visual requirement. Some applications of op-art are in security prints, fashion design, packaging design, architecture, interior design, publishing media, and printing designs. The problem is the few softwares specialized in Op-Art production. These softwares are based on geometric shapes in creating visual art items. Concerning the wide facilities of blend and transform options and effects in Adobe Illustrator software, many op- art items can be investigated. The goal is to highlight the importance of these tools options and effects and its ease, efficiency, and functionality in designing countless variety of op-art items. The availability, prevalence, and ease of use of the Adobe softwares are very important advantages that encourage designers to use in most of their works. The research aims to design Op-Art items by using Illustrator's blend and transform and utilizing these items in various designs. Keywords: Op-Art, Adobe Illustrator, Blend, Transform, packaging design, Guilloche. 1. Introduction 1.1 Op-Art (1965-70) Op Art can be defined as a type of abstract or concrete art consisting of non-representational geometric shapes which create various types of optical illusion. For instance, when viewed, Op Art pictures may cause the eye to detect a sense of movement (eg. -

Jcmac.Art W: Jcmac.Art Hours: T-F 10:30AM-5PM S 11AM-4PM

THE UNBOUNDED LINE A Selection from the Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection Above: Carmelo Arden Quin, Móvil, 1949. 30 x 87 x 95 in. Cover: Alejandro Otero, Coloritmo 75, 1960. 59.06 x 15.75 x 1.94 in. (detail) THE UNBOUNDED LINE A Selection from the Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection 3 Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection was founded in 2005 out of a passion for art and a commitment to deepen our understanding of the abstract-geometric style as a significant part of Latin America’s cultural legacy. The fascinating revolutionary visual statements put forth by artists like Jesús Soto, Lygia Clark, Joaquín Torres-García and Tomás Maldonado directed our investigations not only into Latin American regions but throughout Europe and the United States as well, enriching our survey by revealing complex interconnections that assert the geometric genre's wide relevance. It is with great pleasure that we present The Unbounded Line A Selection from the Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection celebrating the recent opening of Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection’s new home among the thriving community of cultural organizations based in Miami. We look forward to bringing about meaningful dialogues and connections by contributing our own survey of the intricate histories of Latin American art. Juan Carlos Maldonado Founding President Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection Left: Juan Melé, Invención No.58, 1953. 22.06 x 25.81 in. (detail) THE UNBOUNDED LINE The Unbounded Line A Selection from the Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection explores how artists across different geographical and periodical contexts evaluated the nature of art and its place in the world through the pictorial language of geometric abstraction. -

November 23Rd, 2010 Gene Beery

Gene Beery at Algus Greenspon Within Gene Beery’s conceptual language-based paintings, there always seems to be some kind of joke—and not always one that the viewer is in on. Among the pieces included in the artist’s 50-year retrospective was Note (1970), in which the words “NOTE: MAKE A PAINTING OF A NOTE AS A PAINTING” are rendered in puffy, candy-colored letters on a pale background with a black framelike border. In another, the words “life without a sound sense of tra can seem like an incomprehensible nup” (1994) are written in black capital letters on white; the canvas is divided by a thick black line, which cuts through the lines of text so that the reversed words “art” and “pun” are separated from the rest. Gene Beery, Note, 1970, acrylic on canvas, 34 x 42 inches. The exhibition began with works from the late 1950s, when Beery, then employed as a guard at the Museum of Modern Art, was “discovered” by James Rosenquist and Sol LeWitt. An “artist’s artist,” he was championed by artists who were, and would remain, better known than he. After a 1963 show at Alexander Iolas Gallery in New York, Beery moved to the Sierra Nevada mountains, where he still lives. While other artists using text and numbers who emerged in the 1960s—Lawrence Weiner, Joseph Kosuth, On Kawara, for example—produced mostly cerebral works lacking evidence of the artist’s hand, Beery seemingly poked fun at the high Conceptualism of the day. He continued to make his uniquely homespun and humorously irreverent canvases, the rawness of their execution a throwback to the Abstract Expressionists. -

Download Transcript (PDF)

KAWARA: EXHIBITION OVERVIEW Jeffrey Weiss: On Kawara was a key figure in the art of the 1960s in particular. He began working in Japan and continued work in many other cities, finally settling in New York in the mid-’60s, where he was part of the community of Conceptual art during that period of time. He knew a lot of artists that we associate with Conceptualism including Sol LeWitt and Hanne Darboven, Joseph Kosuth and Dan Graham. It’s easy to associate his work, then, with the rise of Conceptualism, although Kawara’s work, when you examine it closely, stands well apart. This exhibition was organized in cooperation with the artist. And I really wanted to show every category of Kawara’s production since around 1964. We don’t call it a retrospective because Kawara’s work is based on time, on the passage of time. So the idea of the retrospective actually doesn’t apply in the conventional sense. Anne Wheeler: We heard from a number of his friends and colleagues from even years ago that it had always been his dream to have a show at the Guggenheim because of the cyclical nature of time and the way that the building represents that in the way that you can move throughout the chronology of his work. In organizing the show we are moving more or less chronologically through the series of his works, starting in the High Gallery with works from 1963 to ’65. Jeffrey Weiss: We’re also showing Paris–New York Drawings, which he produced in Paris and New York, where he was living—both places. -

Ellsworth Kelly and Andy Warhol Lead Swann Galleries' November

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Alexandra Nelson October 25, 2016 Communications Director 212-254-4710 ext. 19 [email protected] Ellsworth Kelly and Andy Warhol Lead Swann Galleries’ November Contemporary Art Auction New York— On Tuesday, November 15, Swann Galleries will hold an auction of Contemporary Art, featuring works by Chuck Close, Christo, Richard Diebenkorn, Claes Oldenburg and Cy Twombly, among others. Prime works by Pop Art king Andy Warhol include the iconic 1964 screenprint of Elizabeth Taylor, aptly titled Liz, as well as the screenprint Campbell’s Soup I: Green Pea, 1968 ($30,000 to $50,000 and $15,000 to $20,000, respectively). Also available is a sheet of sixty unpeeled Banana Stickers (The Velvet Underground & Nico), 1967, the largest amount of intact stickers related to the landmark collaboration between Warhol and The Velvet Underground ever seen at auction, estimated to sell between $8,000 to $12,000. Abstract Expressionist masters are well represented. An excellent work from Robert Motherwell’s Elegy to the Spanish Republic series titled Lament for Lorca, 1981-82, is estimated at $10,000 to $15,000. Willem de Kooning’s first lithograph with printer Irwin Hollander, Woman at Clearwater Beach, 1971, is also present. According to Hollander, the work was inspired by the artist’s “trip to Japan…the seeing and feeling of calligraphy, sumi brush and Zen”—it is expected to realize $8,000 to $12,000. There is also a run of moody works by Adolph Gottlieb. Bridging print and sculpture is Jean Dubuffet’s Parcours, 1981, an unusual scrolled screenprint on silk. -

Aperto Geometrismo E Movimento

Aperto BOLLETTINO DEL GABINETTO DEI DISEGNI E DELLE STAMPE NUMERO 4, 2017 DELLA PINACOTECA NAZIONALE DI BOLOGNA aperto.pinacotecabologna.beniculturali.it Geometrismo e movimento Elisa Baldini Tendenze non figurative di orientamento geometrizzante si affermano in Europa nel secondo dopoguerra. La ricerca della purezza formale contraddistingue il nuovo internazionalismo estetico così come l’attenzione al design e alla “sintesi delle arti”. Erede di una sensibilità determinatasi intorno alla metà del secolo precedente, la propensione dell’arte a confrontarsi con le scoperte scientifiche e tecnologiche è caratteristica determinante della attitudine astrattista di questo periodo e mira a superare la tradizionale dicotomia che contrappone arte e scienza, conducendo la prima sul sentiero della regola armonica e del dominio dell’esattezza. Sopravanzando gli esiti delle ricerche astrattiste delle avanguardie di inizio Novecento, che mantenevano una referenzialità con il mondo fenomenico, l’astrazione alla quale gli artisti del secondo dopoguerra fanno riferimento discende dal pensiero concretista di Theo van Doesburg e i suoi esiti contestano tanto la figurazione quanto l’astrazione lirica. All’esistenzialismo informale che aveva dominato la decade precedente le composite sperimentazioni neoconcrete oppongono la necessità di investigare le ragioni oggettive della vista e della percezione. È così che, in molti casi, la grafica evidenzia la necessità degli autori di esplorare con mezzi diversi le poetiche che caratterizzano le loro ricerche. È il caso di Auguste Herbin (1882 – 1960) che in Composizione astratta (Minuit) del 1959 (Tip. 29813) traduce, senza difficoltà alcuna, la sua pittura, fatta di semplici figure geometriche dai colori puri stesi con grandi pennellate piatte, in serigrafia, mezzo peraltro congeniale a dare risalto al contrasto armonico tra sfondo e figure, caratteristica tipica della ricerca di Herbin fin dagli anni Trenta1. -

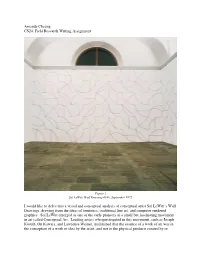

Sol Lewitt's Wall Drawings

Amanda Cheung CS24: Field Research Writing Assignment Figure 1 Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing #146, September 1972 I would like to delve into a visual and conceptual analysis of conceptual artist Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawings, drawing from the ideas of semiotics, traditional fine art, and computer rendered graphics. Sol LeWitt emerged as one of the early pioneers of a small but fascinating movement in art called Conceptual Art. Leading artists who participated in this movement, such as Joseph Kosuth, On Kawara, and Lawrence Weiner, maintained that the essence of a work of art was in the conception of a work or idea by the artist, and not in the physical products created by or representing the idea. For example, in Joseph Kosuth’s “One and Three Chairs,” the artwork is the idea of the chair, represented the word “chair,” a photograph of a chair, and the dictionary definition of chair. The work explores of the idea of the signifier, signified, and referent as studied in semiotics, and questions the role of the artist in creating a work; can he simply conceive an idea and let it be art, aside from any physical product? In Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawings, such as the one pictured in Figure 1, the essence of the work lay in the conception of the specific lines/shapes to be drawn on a wall, and not in the final product. LeWitt’s process involved conceiving the idea for the specific wall drawing and giving instructions to workers who executed the drawings in the exhibition spaces. Thus, a single “Wall Drawing” work would appear differently in different exhibitions because it would be executed by different people and in different spaces. -

About Henry Street Settlement

TO BENEFIT Henry Street Settlement ORGANIZED BY Art Dealers Association of America March 1– 5, Gala Preview February 28 FOUNDED 1962 Park Avenue Armory at 67th Street, New York City MEDIA MATERIALS Lead sponsoring partner of The Art Show The ADAA Announces Program Highlights at the 2017 Edition of The Art Show ART DEALERS ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA 205 Lexington Avenue, Suite #901 New York, NY 10016 [email protected] www.artdealers.org tel: 212.488.5550 fax: 646.688.6809 Images (left to right): Scott Olson, Untitled (2016), courtesy James Cohan; Larry Bell with Untitled (Wedge) at GE Headquarters, Fairfield, CT in 1984, courtesy Anthony Meier Fine Arts; George Inness, A June Day (1881), courtesy Thomas Colville Fine Art. #TheArtShowNYC Program Features Keynote Event with Museum and Cultural Leaders from across the U.S., a Silent Bidding Sale of an Alexander Calder Sculpture to Benefit the ADAA Foundation, and the Annual Art Show Gala Preview to Benefit Henry Street Settlement ADAA Member Galleries Will Present Ambitious Solo Exhibitions, Group Shows, and New Works at The Art Show, March 1–5, 2017 To download hi-res images of highlights of The Art Show, visit http://bit.ly/2kSTTPW New York, January 25, 2017—The Art Dealers Association of America (ADAA) today announced additional program highlights of the 2017 edition of The Art Show. The nation’s most respected and longest-running art fair will take place on March 1-5, 2017, at the Park Avenue Armory in New York, with a Gala Preview on February 28 to benefit Henry Street Settlement. -

Documenta 11

1/21/2015 Frieze Magazine | Archive | Documenta 11 Documenta 11 About this article Documenta 11 Published on 09/09/02 By Thomas McEvilley Each of artistic director Okwui Enwezor’s six co-curators - Sarat Maharaj, Octavio Zaya, Carlos Basualdo, Ute Meta Bauer, Susanne Ghez and Mark Nash - spoke briefly, followed by Enwezor himself. Maharaj identified the point of art today as ‘knowledge production’ and the point of this exhibition as ‘thinking the other’; Nash declared that the exhibition aimed to explore ‘issues of dislocation and migration’ (‘We’re all becoming transnational subjects’, he observed); Ghez stressed the unusual fact that as many as 70% of the works in the show were made explicitly for the Back to the main site occasion; Basualdo spoke of ‘establishing a new geography, or topology, of culture’; and Bauer spoke of ‘deterritorialization’. Finally, Enwezor began his reflections by referring to Chinua Achebe’s classic novel of pre-colonial Africa Things Fall Apart (1958). He spoke of the emergence of post-colonial identity, and said that he and his colleagues had aimed at something much larger than an art exhibition: they were seeking to find out what comes after imperialism. These remarks were significant because Documenta, along with the Venice Biennale, is one of the foremost venues at which the current cultural politics of the art world is laid out. In a sense the agenda proclaimed by these curators gave one a sense of déjà vu; or rather, it seemed not exactly to usher in a new era but to set a seal on an era first announced long ago. -

Download Sol Lewitt's Biography

ARTIST - SOL LEWITT Born in 1928, Hartford, CT, USA Died in 2007, New York, NY, USA EDUCATION - 1949 Syracuse University, B.F.A, NY, USA SOLO SHOWS - 1965 John Daniels Gallery, New York, NY, USA 1966 Dwan Gallery, New York, NY, USA 1967 Dwan Gallery, Los Angeles, NY, USA 1968 Galerie Konrad Fischer, Düsseldorf, Germany Dwan Gallery, New York, NY, USA Galerie Bischofberger, Zürich, Switzerland Galerie Heiner Friederich, Munich, Germany 1968–1969 Ace Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, USA 1969 Galerie Konrad Fischer, Düsseldorf, Germany Galleria L'Attico, Rome, Italy Galerie Ernst, Hannover, Germany Wall Drawings, Dwan Gallery, New York, NY, USA Sol LeWitt: Sculptures and Wall Drawings, Museum Haus Lange, Krefeld, Germany Galerie Bischofberger, Zürich, Switzerland 1970 Art & Project, Amsterdam, Netherlands Wisconsin State University, River Falls, WI, USA Galerie Yvon Lambert, Paris, France Wall Drawings, Galleria Sperone, Turin, Italy Dwan Gallery, New York, NY, USA Lisson Gallery, London, UK Gemeentemuseum, The Hague, Netherlands Galerie Heiner Friederich, Munich, Germany 1970–1971 Pasadena Art Museum, CA, USA 1971 Art & Project, Amsterdam, Netherlands Wall Drawings, Protetch-Rivkin Gallery, Washington D.C., USA Prints and Drawings, Dwan Gallery, New York, NY, USA Lisson Gallery, London, UK Galerie Stampa, Basel, Germany Galleria Toselli, Milano, Italy Informations-Raum 3, Basel, Germany Galerie Konrad Fischer, Düsseldorf, Germany Art & Project, Amsterdam, Netherlands Structures and Wall Drawings, John Weber Gallery, New York, NY, USA Dunkelmann