Aperto Geometrismo E Movimento

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copertina Artepd.Cdr

Trent’anni di chiavi di lettura Siamo arrivati ai trent’anni, quindi siamo in quell’età in cui ci sentiamo maturi senza esserlo del tutto e abbiamo tantissime energie da spendere per il futuro. Sono energie positive, che vengono dal sostegno e dal riconoscimento che il cammino fin qui percorso per far crescere ArtePadova da quella piccola edizio- ne inaugurale del 1990, ci sta portando nella giusta direzione. Siamo qui a rap- presentare in campo nazionale, al meglio per le nostre forze, un settore difficile per il quale non è ammessa l’improvvisazione, ma serve la politica dei piccoli passi; siamo qui a dimostrare con i dati di questa edizione del 2019, che siamo stati seguiti con apprezzamento da un numero crescente di galleristi, di artisti, di appassionati cultori dell’arte. E possiamo anche dire, con un po’ di vanto, che negli anni abbiamo dato il nostro contributo di conoscenza per diffondere tra giovani e meno giovani l’amore per l’arte moderna: a volte snobbata, a volte non compresa, ma sempre motivo di dibattito e di curiosità. Un tentativo questo che da qualche tempo stiamo incentivando con l’apertura ai giovani artisti pro- ponendo anche un’arte accessibile a tutte le tasche: tanto che nei nostri spazi figurano, democraticamente fianco a fianco, opere da decine di migliaia di euro di valore ed altre che si fermano a poche centinaia di euro. Se abbiamo attraversato indenni il confine tra due secoli con le sue crisi, è per- ché l’arte è sì bene rifugio, ma sostanzialmente rappresenta il bello, dimostra che l’uomo è capace di grandi azzardi e di mettersi sempre in gioco sperimen- tando forme nuove di espressione; l’arte è tecnica e insieme fantasia, ovvero un connubio unico e per questo quasi magico tra terra e cielo. -

Utilizing Adobe Illustrator's Blend and Transform in Designing Op-Art Items

Arts and Design Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-6061 (Paper) ISSN 2225-059X (Online) Vol.44, 2016 Utilizing Adobe Illustrator's Blend and Transform in Designing Op-Art Items Randa Darwish Mohamed Assistant Professor in Printing, Publishing and Packaging Dept., Faculty of Applied Arts, Helwan University, Egypt. Abstract Op-Art can strengthen the product image and can combine culture elements which satisfies consumers’ visual requirement. Some applications of op-art are in security prints, fashion design, packaging design, architecture, interior design, publishing media, and printing designs. The problem is the few softwares specialized in Op-Art production. These softwares are based on geometric shapes in creating visual art items. Concerning the wide facilities of blend and transform options and effects in Adobe Illustrator software, many op- art items can be investigated. The goal is to highlight the importance of these tools options and effects and its ease, efficiency, and functionality in designing countless variety of op-art items. The availability, prevalence, and ease of use of the Adobe softwares are very important advantages that encourage designers to use in most of their works. The research aims to design Op-Art items by using Illustrator's blend and transform and utilizing these items in various designs. Keywords: Op-Art, Adobe Illustrator, Blend, Transform, packaging design, Guilloche. 1. Introduction 1.1 Op-Art (1965-70) Op Art can be defined as a type of abstract or concrete art consisting of non-representational geometric shapes which create various types of optical illusion. For instance, when viewed, Op Art pictures may cause the eye to detect a sense of movement (eg. -

Jcmac.Art W: Jcmac.Art Hours: T-F 10:30AM-5PM S 11AM-4PM

THE UNBOUNDED LINE A Selection from the Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection Above: Carmelo Arden Quin, Móvil, 1949. 30 x 87 x 95 in. Cover: Alejandro Otero, Coloritmo 75, 1960. 59.06 x 15.75 x 1.94 in. (detail) THE UNBOUNDED LINE A Selection from the Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection 3 Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection was founded in 2005 out of a passion for art and a commitment to deepen our understanding of the abstract-geometric style as a significant part of Latin America’s cultural legacy. The fascinating revolutionary visual statements put forth by artists like Jesús Soto, Lygia Clark, Joaquín Torres-García and Tomás Maldonado directed our investigations not only into Latin American regions but throughout Europe and the United States as well, enriching our survey by revealing complex interconnections that assert the geometric genre's wide relevance. It is with great pleasure that we present The Unbounded Line A Selection from the Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection celebrating the recent opening of Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection’s new home among the thriving community of cultural organizations based in Miami. We look forward to bringing about meaningful dialogues and connections by contributing our own survey of the intricate histories of Latin American art. Juan Carlos Maldonado Founding President Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection Left: Juan Melé, Invención No.58, 1953. 22.06 x 25.81 in. (detail) THE UNBOUNDED LINE The Unbounded Line A Selection from the Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection explores how artists across different geographical and periodical contexts evaluated the nature of art and its place in the world through the pictorial language of geometric abstraction. -

Kinetic Masters & Their Legacy (Exhibition Catalogue)

KINETIC MASTERS & THEIR LEGACY CECILIA DE TORRES, LTD. KINETIC MASTERS & THEIR LEGACY OCTOBER 3, 2019 - JANUARY 11, 2020 CECILIA DE TORRES, LTD. We are grateful to María Inés Sicardi and the Sicardi-Ayers-Bacino Gallery team for their collaboration and assistance in realizing this exhibition. We sincerely thank the lenders who understood our desire to present work of the highest quality, and special thanks to our colleague Debbie Frydman whose suggestion to further explore kineticism resulted in Kinetic Masters & Their Legacy. LE MOUVEMENT - KINETIC ART INTO THE 21ST CENTURY In 1950s France, there was an active interaction and artistic exchange between the country’s capital and South America. Vasarely and many Alexander Calder put it so beautifully when he said: “Just as one composes colors, or forms, of the Grupo Madí artists had an exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires in 1957 so one can compose motions.” that was extremely influential upon younger generation avant-garde artists. Many South Americans, such as the triumvirate of Venezuelan Kinetic Masters & Their Legacy is comprised of a selection of works created by South American artists ranging from the 1950s to the present day. In showing contemporary cinetismo–Jesús Rafael Soto, Carlos Cruz-Diez, pieces alongside mid-century modern work, our exhibition provides an account of and Alejandro Otero—settled in Paris, amongst the trajectory of varied techniques, theoretical approaches, and materials that have a number of other artists from Argentina, Brazil, evolved across the legacy of the field of Kinetic Art. Venezuela, and Uruguay, who exhibited at the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles. -

Art in Europe 1945 — 1968 the Continent That the EU Does Not Know

Art in Europe 1945 Art in — 1968 The Continent EU Does that the Not Know 1968 The The Continent that the EU Does Not Know Art in Europe 1945 — 1968 Supplement to the exhibition catalogue Art in Europe 1945 – 1968. The Continent that the EU Does Not Know Phase 1: Phase 2: Phase 3: Trauma and Remembrance Abstraction The Crisis of Easel Painting Trauma and Remembrance Art Informel and Tachism – Material Painting – 33 Gestures of Abstraction The Painting as an Object 43 49 The Cold War 39 Arte Povera as an Artistic Guerilla Tactic 53 Phase 6: Phase 7: Phase 8: New Visions and Tendencies New Forms of Interactivity Action Art Kinetic, Optical, and Light Art – The Audience as Performer The Artist as Performer The Reality of Movement, 101 105 the Viewer, and Light 73 New Visions 81 Neo-Constructivism 85 New Tendencies 89 Cybernetics and Computer Art – From Design to Programming 94 Visionary Architecture 97 Art in Europe 1945 – 1968. The Continent that the EU Does Not Know Introduction Praga Magica PETER WEIBEL MICHAEL BIELICKY 5 29 Phase 4: Phase 5: The Destruction of the From Representation Means of Representation to Reality The Destruction of the Means Nouveau Réalisme – of Representation A Dialog with the Real Things 57 61 Pop Art in the East and West 68 Phase 9: Phase 10: Conceptual Art Media Art The Concept of Image as From Space-based Concept Script to Time-based Imagery 115 121 Art in Europe 1945 – 1968. The Continent that the EU Does Not Know ZKM_Atria 1+2 October 22, 2016 – January 29, 2017 4 At the initiative of the State Museum Exhibition Introduction Center ROSIZO and the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow, the institutions of the Center for Fine Arts Brussels (BOZAR), the Pushkin Museum, and ROSIZIO planned and organized the major exhibition Art in Europe 1945–1968 in collaboration with the ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe. -

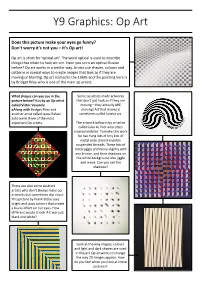

Y9 Graphics: Op Art

Y9 Graphics: Op Art Does this picture make your eyes go funny? Don't worry it's not you – it's Op art! Op art is short for 'optical art'. The word optical is used to describe things that relate to how we see. Have you seen an optical Illusion before? Op art works in a similar way. Artists use shapes, colours and patterns in special ways to create images that look as if they are moving or blurring. Op art started in the 1960s and the painting here is by Bridget Riley who is one of the main op artists. What shapes can you see in the Some op artists made artworks picture below? It is by an Op artist that don't just look as if they are called Victor Vasarely. moving – they actually ARE aAlong with Bridget Riley and moving! Art that moves is another artist called Jesus Rafael sometimes called kinetic art. Soto were three of the most important Op artists. The artwork below is by an artist called Julio Le Parc who often created mobiles. To make this work he has hung lots of tiny bits of metal onto almost invisible suspended threads. These bits of metal jiggle and move slightly with any breeze, and their shadows on the white background also jiggle and move. Can you see the shadows? There are also some abstract artists who don't always make op artworks but sometimes slip into it. This picture by Frank Stella uses bright and jazzy colours that create a buzzy effect on our eyes. -

Download Document

Josef Albers Max Bill Piero Dorazio Manuel Espinosa Friedrich Vordemberge-Gildewart Manuel Espinosa in Europe Josef Albers Max Bill Piero Dorazio Manuel Espinosa Friedrich Vordemberge-Gildewart Frieze Masters 2019 - Stand E7 Manuel Espinosa and his European Grand Tour Dr. Flavia Frigeri Once upon a time, it was fashionable among young members of the British and northern European upper classes to embark on what came to be known as the Grand Tour. A rite of passage of sorts, the Grand Tour was predicated on the exploration of classical antiquity and Renaissance masterpieces encountered on a pilgrimage extending from France all the way to Greece. Underpinning this journey of discovery was a sense of cultural elevation, which in turn fostered a revival of classical ideals and gave birth to an international network of artists and thinkers. The Grand Tour reached its apex in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, after which interest in the great classical beauties of France, Italy and Greece slowly waned.1 Fast-forward to 1951, the year in which the Argentine artist Manuel Espinosa left his native Buenos Aires to embark on his own Grand Tour of Europe. Unlike his cultural forefathers, Espinosa was not lured by 4 Fig. 1 Founding members of the Concrete-Invention Art Association pictured in 1946. Espinosa is third from the right, back row. Photo: Saderman. the qualities of classical and Renaissance Europe, but what propelled him to cross an ocean and spend an extended period of time away from home was the need to establish a dialogue with his abstract-concrete European peers. -

Press Release Mazzoleni at Art Basel Miami Beach 7 – 10 December 2017 Preview: Wednesday, 6 December 2017

Press Release Mazzoleni at Art Basel Miami Beach 7 – 10 December 2017 Preview: Wednesday, 6 December 2017 Mazzoleni will return to Art Basel Miami Beach for the third year running this December. The 2017 presentation will be inspired by the rich artistic exchange between Italy and the United States in the 1950s and 1960s, bringing together works by several Italian masters, including Afro (1912–1976), Getulio Alviani (b.1939), Agostino Bonalumi (1935–2013), Alberto Burri (1915–1995), Giuseppe Capogrossi (1900–1972), Enrico Castellani (b. 1930), Piero Dorazio (1927–2005), Lucio Fontana (1899–1968) and Tancredi (1927–1964). A renewed interest from American museums in Italy’s art at the end of the 1940s fostered a “New Italian Renaissance” in the aftermath of World War II. In 1949, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, held the ‘Twentieth Century Italian Art’ exhibition, showcasing the country’s burgeoning talent, including Afro and Fontana. During this period, the Italian-American art dealer Catherine Viviano opened a gallery in New York, which played a key role in the flourishing of Italian Post-War art for two decades. Mazzoleni’s presentation will explore how Viviano launched Afro’s career in the US giving him his first solo show in 1953. With support from Viviano and the Galleria dell’Obelisco in Rome, Afro became one of the most successful Italian artists in the US. In 1955, Afro, along with Alberto Burri and Giuseppe Capogrossi participated in MoMA’s milestone exhibition ‘The New Decade: 22 European Painters and Sculptors’. During this same period, James John Sweeney, second director of the Solomon R. -

Julio Le Parc

GALERIE BUGADA & CARGNEL PARIS JULIO LE PARC Hall 2.0, stand G12 1 Julio Le Parc with Continuel-Lumière Cylindre in 1962 On the cover: Julio Le Parc with Continuel-Lumière Cylindre 1962 - 2012 wood, plexiglas, motor, light bulb 510 x 460 x 140 cm exhibition view, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2013 2 JULIO LE PARC “Generally speaking, I have tried, Historic figure and committed artist, Julio Le Parc (b. 1928) is a major figure through my experiments, to elicit a in Op and Kinetic art, founding member of G.R.A.V. (Groupe de Recherche different type of behavior from the d’Art Visuel, or Visual Art Research Group) and recipient of the Grand Prize for viewer […] to seek, together with the Painting at the 1966 Venice Biennale. This socially conscious artist was expelled public, various means of fighting off from France after the events of May 1968. A defender of human rights, he passivity, dependency or ideological fought against dictatorship in Latin America. In 1972, when the Musée d’Art conditioning, by developing reflective, Moderne de la Ville de Paris offered him a large retrospective, Le Parc decided comparative, analytical, creative whether or not to accept by flipping a coin: the exhibition did not take place. or active capacities.” Julio Le Parc Julio Le Parc creates interactive, social art. More than a mere play of light and shapes, his works are activated by the viewer’s physical interac- tion: movements of the retina, of the body, activate paintings, sculptures and installations that, as the artist insists, seek to “elicit a different behavior from the spectator […] and try to search alongside the public for the means of combating passivity, dependence or ideological conditioning, and to develop capacities for reflection, comparison, analysis, creation and action.” Particularly explorative of the spectator’s role, the artist creates work that is, in his own words, both interactive and unstable. -

Atti Dell' Accademia

Atti dell’ Accademia Accademia Nazionale di San Luca Atti 2009 - 2010 direttore responsabile Francesco Moschini a cura di Nicola Carrino atti cura redazionale, editing e impaginati 2009 – 2010 Laura Bertolaccini consulenza per la grafica Benedetta Vangi segreteria Isabella Fiorentino Anna Maria De Gregorio Giulia Frisardi si ringrazia Giampiero Bucci Elisa Camboni Rosa Maria Facciolo Angelo Ferretti Alessio Miccinilli This magazine is indexed in BHA - Bibliography of the History of Art A bibliographic service of the Getty Research Institute and the Institut de l’Information Scientifique et Technique of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique Stampato in Italia da Beniamini GD&P - Roma © Copyright 2011 Accademia Nazionale di San Luca www.accademiasanluca.it issn 2239-8341 isbn 978-88-97610-02 Albo Accademico 2009-2010 Indice Presidenza Accademici Nazionali Guido Canella † Accademici Cultori Massimo Carmassi Presidente Pittori Giuseppe Appella Presentazione Francesco Cellini 7 Nicola Carrino Getulio Alviani Renato Barilli Nicola Carrino Michele De Lucchi Vasco Bendini Paola Barocchi Vice Presidente Pietro Derossi Agostino Bonalumi Evelina Borea 9 Un nuovo inizio Guido Strazza Massimiliano Fuksas Eugenio Carmi Arnaldo Bruschi † Francesco Moschini Vittorio Gregotti Ex Presidente Bruno Caruso Howard Burns Guido Canella † Glauco Gresleri Enrico Castelnuovo Leonardo Cremonini † Danilo Guerri Lucio Passarelli Enzo Cucchi Giorgio Ciucci Giuseppina Marcialis Jean-Louis Cohen Accademico Amministratore Gianni Dessì Carlo Melograni Incontri -

Jesús Rafael Soto 1923, Ciudad Bolívar (Venezuela) - 2005, Paris (France) Ground Level

Jesús Rafael Soto 1923, Ciudad Bolívar (Venezuela) - 2005, Paris (France) GROUND LEVEL SOLO SHOWS (Selection) 2015 “Chronochrome” Galerie Perrotin, Paris and New York 2014-2015 “Pénétrable de Chicago”, The Art Institute of Chicago (6 October-15 March) 2014 “Jesús Rafael Soto: Houston Penetrable”, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, USA “Petite progression “Ecriture (Ecriture “Progresión elíptica “Ecriture Fiac 99”, “Grand Tes Jaune” 2013 “Soto dans la collection du Musée National d’Art Moderne”, Centre Pompidou, Paris 2012 “Soto: Paris and Beyond, 1950-1970”, Grey Art Gallery, New York (10 January-31 March) rosa et blanche”, 1976 noire)”, 1982 rosa y blanca”, 1974 1999 1979 2005 “Soto – A construcao da imaterialidade”, Centro cultural Banco do brasil, Rio de Janeiro (27 April-3 July) Paint on metal Paint on wood and Paint on metal Paint on wood and Paint on wood and metal 1997 “Jesús Rafael Soto”, Galerie nationale du Jeu de Paume, Paris (January-March) 14 x 50 x 50 cm metal, nylon 260 x 243 x 150 cm metal, nylon 253 x 253 x 17 cm 1/4 3/4 1/16 1/2 1/2 3/4 touring: Stiftung fur Konkrete Kunst, Reutlingen, Germany (20 April-22 September) 51/2 x 193/4 x 193/4 in. 250 x 506 x 30 cm 102 x 95 x 59 in. 208 x 203 x 40 cm 99 x 99 x 6 in. 1/2 1/4 3/4 3/4 3/4 1993 “Retrospective”, Fundação de Serralves, Porto (April-June); touring: Musée des Beaux-arts de Pau, France (January – March) 98 x 199 x 11 in. -

Julio Le Parc: 1959 - 1970 Galeria Nara Roesler | New York

julio le parc: 1959 - 1970 galeria nara roesler | new york exhibition october 7th - december 17th, 2016 mon - sat | 10am - 6pm [email protected] nararoesler.com.br exhibition view -- galeria nara roesler | new york -- 2016 Julio Le Parc A Constant Quest Estrellita B. Brodsky This essay was previously published to accompany the exhibition A Constant Quest, at Galeria Nara Roesler | São Paulo (oct. 10th - dec. 12th, 2013). During the course of six decades, Julio Le Parc has consistently sought to redefine the very nature of the art experience, pre- cipitating what he calls ‘disturbances in the artistic system’. In so doing, he has played with the viewers’ sensory experiences and given spectators an active role. With fellow members of the Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel (GRAV)—an artist collec- tive Le Parc established with Horacio García Rossi, Francisco Sobrino, François Morellet, Joël Stein, and Jean-Pierre Vasarely (Yvaral) in Paris in 1960—Le Parc generated direct encounters with the public, while undermining what they considered the artificial constraints of institutional frameworks.1 As their manifesto Assez de mystifications [“Enough Mystifications”, Paris, 1961] announced, the group’s intention was to find ways to confront the public with artwork outside the museum setting by intervening in urban spaces with subversive games, politically charged flyers, and playful questionnaires.2 Through such strategies, Le Parc and GRAV turned spectators into par- ticipants with an increased self-awareness, both achieving a form of social leveling and anticipating some of the sociopoliti- cal collaborative and relational strategies that have proliferated over the past two decades.