Dan Graham Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D'art Ambition D'art Alighiero Boetti, Daniel Buren, Jordi Colomer, Tony

Ambition d’art AmbitionAlighiero Boetti, Daniel Buren, Jordi Colomer, Tony Cragg, Luciano Fabro, Yona Friedman, Anish Kapoor, On Kawara, Martha Rosler, Jeff Wall, Lawrence Weiner d’art16 May – 21 September 2008 The Institut d’art contemporain aspect (an anniversary) and the is celebrating its 30th anniversary setting – the inauguration of an in 2008 and on this occasion exhibition in the artistico-political has invited its founder, context of the 2000s – it is aimed Jean Louis Maubant, to design at shedding light on what the an exhibition, accompanied by an ‘ambition’ of art and its ‘world’ important publication. might be. The exhibition Ambition d’art, held in partnership with the The retrospective dimension Rhône-Alpes Regional Council of the event is presented above and the town of Villeurbanne, is a all in the two volumes (Alphabet strong and exceptional event for and Archive) of the publication to the Institute: beyond the anecdotal which it has given rise. Institut d’art contemporain, Villeurbanne www.i-art-c.org Any feedback in the exhibition is Yona Friedman, Jordi Colomer) or less to commemorate past history because they have hardly ever been than to give present and future shown (Martha Rosler, Alighiero history more density. In fact, many Boetti, Jeff Wall). Other works have of the works shown here have already been shown at the Institut never been seen before. and now gain fresh visibility as a result of their positioning in space and their artistic company (Luciano Fabro, Daniel Buren, Martha Rosler, Ambition d’art Tony Cragg, On Kawara). For the exhibition Ambition d’art, At the two ends of the generation Jean Louis Maubant has chosen chain, invitations have been eleven artists for the eleven rooms extended to both Jordi Colomer of the Institut d’art contemporain. -

This Part That Seemingly Needs to Get out Through

This Part That Seemingly Needs to Get Out This multiplicity of positions reinforces yet through a Place in My Body again the complex dimension of this topic and the difficulty of setting it within a rigid This exhibition is a proposal that tests its framework. But however complicated such own approach and methodology and an initiative might prove to be, it is to be accepts its own inevitably fragmentary hoped that it will draw attention to a vast nature, induced by instances of institutional social and cultural phenomenon—emigration conditioning, as well as by the intrinsic and exile during the Cold War—that is volatility of the subject. It is a reflection on a essential to an understanding of the way in phenomenon examined all too little in the which the artistic field was configured in context of Romanian contemporary art: the Romania, with an undeniable impact on how migration of Romanian artists to the West it looks today. In times of global migration, during the communist period, and focuses when mobility and human interactions unfold more closely on the late 1960s and the according to completely different 1970s. Restricting the scope of the coordinates, it is important that we examination even further, it is important to remember a period when the chance to point out that the exhibition highlights the travel abroad could completely and careers of artists active in Bucharest before irrevocably change the course of a person’s emigrating to the West at various times. life. Reactivating the memory of those Some among them are figures well known decades today becomes all the more internationally, albeit not yet fully assimilated necessary since a fast approaching into the canons of world art history. -

ARTIST - DENNIS OPPENHEIM Born in Electric City, WA, USA, in 1938 Died in New York, NY, USA, in 2011

ARTIST - DENNIS OPPENHEIM Born in Electric City, WA, USA, in 1938 Died in New York, NY, USA, in 2011 EDUCATION - 1964 : Beaux Arts of California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, CA, USA 1967 : Beaux Arts of Stantford University, Palo Alto, CA, US SOLO SHOWS (SELECTION) - 2020 Dennis Oppenheim, Galerie Mitterrand, Paris, France 2019 Dennis Oppenheim, Le dessin hors papier, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Caen, FR 2018 Broken Record Blues, Peder Lund, Oslo NO Violations, Marlborough Contemporary, New York US Straight Red Trees. Alternative Landscape Components, Guild Hall, East Hampton, NY, US 2016 Terrestrial Studio, Storm King Art Center, New Windsor US Three Projections, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, US 2015 Collection, MAMCO, Geneva, CH Launching Structure #3. An Armature for Projections, Halle-Nord, Geneva CH Dennis Oppenheim, Wooson Gallery, Daegu, KR 2014 Dennis Oppenheim, MOT International, London, UK 2013 Thought Collision Factories, Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, UK Sculpture 1979/2006, Galleria Fumagalli & Spazio Borgogno, Milano, IT Alternative Landscape Components, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, West Bretton, UK 2012 Electric City, Kunst Merano Arte, Merano, IT 1968: Earthworks and Ground Systems, Haines Gallery, San Francisco US HaBeer, Beersheba, ISR Selected Works, Palacio Almudi, Murcia, ES 2011 Dennis Oppenheim, Musee d'Art Moderne et Contemporain, Saint-Etienne, FR Eaton Fine Arts, West Palm Beach, Florida, US Galerie Samuel Lallouz, Montreal, CA Salutations to the Sky, Museo Fundacion Gabarron, New York, US 79 RUE DU TEMPLE -

November 23Rd, 2010 Gene Beery

Gene Beery at Algus Greenspon Within Gene Beery’s conceptual language-based paintings, there always seems to be some kind of joke—and not always one that the viewer is in on. Among the pieces included in the artist’s 50-year retrospective was Note (1970), in which the words “NOTE: MAKE A PAINTING OF A NOTE AS A PAINTING” are rendered in puffy, candy-colored letters on a pale background with a black framelike border. In another, the words “life without a sound sense of tra can seem like an incomprehensible nup” (1994) are written in black capital letters on white; the canvas is divided by a thick black line, which cuts through the lines of text so that the reversed words “art” and “pun” are separated from the rest. Gene Beery, Note, 1970, acrylic on canvas, 34 x 42 inches. The exhibition began with works from the late 1950s, when Beery, then employed as a guard at the Museum of Modern Art, was “discovered” by James Rosenquist and Sol LeWitt. An “artist’s artist,” he was championed by artists who were, and would remain, better known than he. After a 1963 show at Alexander Iolas Gallery in New York, Beery moved to the Sierra Nevada mountains, where he still lives. While other artists using text and numbers who emerged in the 1960s—Lawrence Weiner, Joseph Kosuth, On Kawara, for example—produced mostly cerebral works lacking evidence of the artist’s hand, Beery seemingly poked fun at the high Conceptualism of the day. He continued to make his uniquely homespun and humorously irreverent canvases, the rawness of their execution a throwback to the Abstract Expressionists. -

Download Transcript (PDF)

KAWARA: EXHIBITION OVERVIEW Jeffrey Weiss: On Kawara was a key figure in the art of the 1960s in particular. He began working in Japan and continued work in many other cities, finally settling in New York in the mid-’60s, where he was part of the community of Conceptual art during that period of time. He knew a lot of artists that we associate with Conceptualism including Sol LeWitt and Hanne Darboven, Joseph Kosuth and Dan Graham. It’s easy to associate his work, then, with the rise of Conceptualism, although Kawara’s work, when you examine it closely, stands well apart. This exhibition was organized in cooperation with the artist. And I really wanted to show every category of Kawara’s production since around 1964. We don’t call it a retrospective because Kawara’s work is based on time, on the passage of time. So the idea of the retrospective actually doesn’t apply in the conventional sense. Anne Wheeler: We heard from a number of his friends and colleagues from even years ago that it had always been his dream to have a show at the Guggenheim because of the cyclical nature of time and the way that the building represents that in the way that you can move throughout the chronology of his work. In organizing the show we are moving more or less chronologically through the series of his works, starting in the High Gallery with works from 1963 to ’65. Jeffrey Weiss: We’re also showing Paris–New York Drawings, which he produced in Paris and New York, where he was living—both places. -

Press Dan Graham: Mirror Complexities Border Crossings

MARIAN GOODMAN GALLERY Dan Graham: Mirror Complexities By Robert Enright and Meeka Walsh (Winter 2009) Public Space/Two Audiences, 1976. Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York “I like to get into new areas,” Dan Graham says in the following interview, “and I like them to be in a borderline situation, rather than definitively one thing.” For over 50 years, Graham has located himself in a number of borderline situations, and from that position of in-betweenness has made an art of perplexing simplicity. Critics generally assign his Schema, 1966, a series of instructional sheets that gave editors sets of data for the composition of printed pages, a generative place in the history of conceptual art. But the various Schema were themselves in border zones of their own, part poetry, part criticism, part visual art. Their newness was in their indeterminacy. Similarly, the deliberately uninflected and abstract photographs he took in 1966 of tract houses, storage tanks, warehouses, motels, trucks and restaurants, subjects he passed in the train on his way into New York from the suburbs, occupied two zones in his mind. In his own estimation, he was “trying to make Donald Judds in photographs.” His first pavilions, beginning with Public Space/Two Audiences made for the Venice Biennale in 1976, were a cross between architecture and sculpture. His cross-disciplinary mobility functioned in all directions: Sol LeWitt’s early sculptures encouraged Graham’s interest in urbanism because the sculptures seemed to him to be about city grids. It’s because of this overall sense of one category of art drifting into another that Graham says, “all my work is a hybrid.” His idea of hybridity was predicated upon an intense degree of experiential involvement; in performance/video works like Nude Two Consciousness Projection(s), 1975, and Intention Intentionality Sequence, 1972, the audience was part of the performance; just as audience involvement was also critical in a number of the pavilions. -

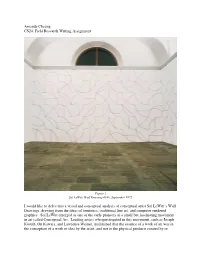

Sol Lewitt's Wall Drawings

Amanda Cheung CS24: Field Research Writing Assignment Figure 1 Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing #146, September 1972 I would like to delve into a visual and conceptual analysis of conceptual artist Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawings, drawing from the ideas of semiotics, traditional fine art, and computer rendered graphics. Sol LeWitt emerged as one of the early pioneers of a small but fascinating movement in art called Conceptual Art. Leading artists who participated in this movement, such as Joseph Kosuth, On Kawara, and Lawrence Weiner, maintained that the essence of a work of art was in the conception of a work or idea by the artist, and not in the physical products created by or representing the idea. For example, in Joseph Kosuth’s “One and Three Chairs,” the artwork is the idea of the chair, represented the word “chair,” a photograph of a chair, and the dictionary definition of chair. The work explores of the idea of the signifier, signified, and referent as studied in semiotics, and questions the role of the artist in creating a work; can he simply conceive an idea and let it be art, aside from any physical product? In Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawings, such as the one pictured in Figure 1, the essence of the work lay in the conception of the specific lines/shapes to be drawn on a wall, and not in the final product. LeWitt’s process involved conceiving the idea for the specific wall drawing and giving instructions to workers who executed the drawings in the exhibition spaces. Thus, a single “Wall Drawing” work would appear differently in different exhibitions because it would be executed by different people and in different spaces. -

Press Release

Press Release Dan Graham Rock ‘n’ Roll 3 October – 3 November 2018 27 Bell Street, London Opening: 2 October, 6 – 8pm For his tenth exhibition with Lisson Gallery, Dan Graham draws on his long-standing history working with music and performance to present a new stage-set design, alongside over-sized models, video and a courtyard pavilion, exploring the relationship between audience and performer. Based in New York, Graham is an icon of Conceptual art, emerging in the 1960s alongside artists such as Dan Flavin, Donald Judd and Sol LeWitt. A hybrid artist, he has been at the forefront of many of the most significant artistic developments of the last half-century, including site-specific sculpture, video and film installation, conceptual and performance art, as well as social and cultural analysis through his extensive writings. Delving into the performative in the early 1970s – exploring shifts in individual and group consciousness, and the limits of public and private space – Graham’s practice evolved into the installations and pavilions for which he is famous internationally. Today, his work continues to evolve with the world around it, taking on a different reading in the age of social media, photography and obsessive self-documentation. A recent work such as Child’s Play (2015-2016), which was on display recently in Museum of Modern Art’s Sculpture Garden, is from a group of works that Graham describes as fun houses for children and photo ops for parents. The artist’s latest presentation of work focuses on the relationship between musical performance and audience. The space at 27 Bell Street will be occupied by a curvilinear stage-set which visitors will be able to walk around. -

Marian Goodman Gallery Robert Smithson

MARIAN GOODMAN GALLERY ROBERT SMITHSON Born: Passaic, New Jersey, 1938 Died: Amarillo, Texas, 1973 SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Robert Smithson: Time Crystals, University of Queensland, BrisBane; Monash University Art Museum, MelBourne 2015 Robert Smithson: Pop, James Cohan, New York, New York 2014 Robert Smithson: New Jersey Earthworks, Montclair Museum of Art, Montclair, New Jersey 2013 Robert Smithson in Texas, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, Texas 2012 Robert Smithson: The Invention of Landscape, Museum für Gegenwartskunst Siegen, Unteres Schloss, Germany; Reykjavik Art Museum, Reykjavik, Iceland 2011 Robert Smithson in Emmen, Broken Circle/Spiral Hill Revisited, CBK Emmen (Center for Visual Arts), Emmen, the Netherlands 2010 IKONS, Religious Drawings and Sculptures from 1960, Art Basel 41, Basel, Switzerland 2008 Robert Smithson POP Works, 1961-1964, Art Kabinett, Art Basel Miami Beach, Miami, Florida 2004 Robert Smithson, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, California; Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, Texas; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, New York 2003 Robert Smithson in Vancouver: A Fragment of a Greater Fragmentation, Vancouver Art Gallery, Canada Rundown, curated by Cornelia Lauf and Elyse Goldberg, American Academy in Rome, Italy 2001 Mapping Dislocations, James Cohan Gallery, New York 2000 Robert Smithson, curated by Eva Schmidt, Kai Voeckler, Sabine Folie, Kunsthalle Wein am Karlsplatz, Vienna, Austria new york paris london www.mariangoodman.com MARIAN GOODMAN GALLERY Robert Smithson: The Spiral Jetty, organized -

GNR SP | Dan Graham | Preview with Installs | EN.Indd

exhibition view, galeria nara roesler | são paulo, 2017 exhibition view, galeria nara roesler | são paulo, 2017 exhibition view, galeria nara roesler | são paulo, 2017 exhibition view, galeria nara roesler | são paulo, 2017 exhibition view, galeria nara roesler | são paulo, 2017 Galeria Nara Roesler | São Paulo is pleased to present a solo exhibition of Dan Graham’s works (b. Urbana, IL, USA, 1942), on view August 12 through November 12, 2017. The first exhibition of Graham’s work at Galeria Nara Roesler features Pavilion (2016), a new work created specifically for the occasion, in addition to six untitled maquettes (2011–2016) and the video work Death by Chocolate: West Edmonton Shopping Mall (1986–2005). Parallel to the exhibition, the Museum of Image and Sound will screen two of the artist’s emblematic video works: Rock My Religion (1982–1984) and Don’t Trust Anyone Over 30 (2004). Presented in collaboration with Galeria Nara Roesler, the screenings will take place at the museum on Sunday, August 13, at 4pm, followed by a roundtable with guests including Marta Bogéa, Agnaldo Farias and Solange Farkas, who will engage in a discussion about Graham’s works, also at the Museum. Untitled, 2016 2-way mirror glass, aluminium, MDF and acrylic ed 1/3 42 x 107 x 125 cm Sem Título, 2016 2-way mirror glass, aluminium, MDF and acrylic 42 x 107 x 125 cm Untitled, 2011 2-way mirror glass, aluminium, MDF and acrylic ed 1/3 71 x 107 x 107 cm Exhibited across the globe, Dan Graham’s pavilions are emblematic of his critical engagement with the visual and cognitive parameters of architectural language within and outside of art institutions. -

Documenta 11

1/21/2015 Frieze Magazine | Archive | Documenta 11 Documenta 11 About this article Documenta 11 Published on 09/09/02 By Thomas McEvilley Each of artistic director Okwui Enwezor’s six co-curators - Sarat Maharaj, Octavio Zaya, Carlos Basualdo, Ute Meta Bauer, Susanne Ghez and Mark Nash - spoke briefly, followed by Enwezor himself. Maharaj identified the point of art today as ‘knowledge production’ and the point of this exhibition as ‘thinking the other’; Nash declared that the exhibition aimed to explore ‘issues of dislocation and migration’ (‘We’re all becoming transnational subjects’, he observed); Ghez stressed the unusual fact that as many as 70% of the works in the show were made explicitly for the Back to the main site occasion; Basualdo spoke of ‘establishing a new geography, or topology, of culture’; and Bauer spoke of ‘deterritorialization’. Finally, Enwezor began his reflections by referring to Chinua Achebe’s classic novel of pre-colonial Africa Things Fall Apart (1958). He spoke of the emergence of post-colonial identity, and said that he and his colleagues had aimed at something much larger than an art exhibition: they were seeking to find out what comes after imperialism. These remarks were significant because Documenta, along with the Venice Biennale, is one of the foremost venues at which the current cultural politics of the art world is laid out. In a sense the agenda proclaimed by these curators gave one a sense of déjà vu; or rather, it seemed not exactly to usher in a new era but to set a seal on an era first announced long ago. -

Press Dan Graham: Whitney Museum of American Art Artforum, October

MARIAN GOODMAN GALLERY Dan Graham: WHITNEY MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ART By Hal Foster (October 2009) OF ACTIVE ARTISTS over the age of sixty in the United States, Dan Graham may be the most admired figure among younger practitioners. Though never as famous as his peers Robert Smithson, Richard Serra, and Bruce Nauman, Graham has now gained, as artist-critic John Miller puts it, a “retrospective public.” Why might this be so? “Dan Graham: Beyond,” the excellent survey curated by Bennett Simpson of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (the show’s inaugural venue), and Chrissie Iles of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, offers ample reasons. If Minimalism was a crux in postwar art, a final closing of the modernist paradigm of autonomous painting and a definitive opening of practices involving actual bodies in social spaces, its potential still had to be activated, and with his colleagues Graham did just that. (This moment is nicely narrated by Rhea Anastas in the catalogue for the show.) “All my work is a critique of Minimal art,” Graham states (in an intriguing interview with artist Rodney Graham also in the catalogue); “it begins with Minimal art, but it’s about spectators observing themselves as they’re observed by other people.” Hence many of the forms associated with his work: interactions between two performers; performances by the artist that directly engage audiences; films and videos reflexive about the space of their making; installations involving viewers in partitions, mirrors, and/or videos; architectural models; and pavilions of translucent and reflective glass.