James Lee Byars 1/2 an Autobiography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

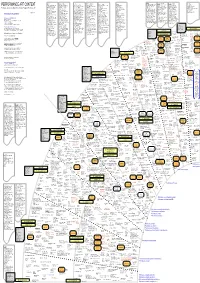

Constellation & Correspondences

LIBRARY CONSTELLATION & CORRESPONDENCES AND NETWORKING BETWEEN ARTISTS ARCHIVES 1970 –1980 KATHY ACKER (RIPOFF RED & THE BLACK TARANTULA) MAC ADAMS ART & LANGUAGE DANA ATCHLEY (THE EXHIBITION COLORADO SPACEMAN) ANNA BANANA ROBERT BARRY JOHN JACK BAYLIN ALLAN BEALY PETER BENCHLEY KATHRYN BIGELOW BILL BISSETT MEL BOCHNER PAUL-ÉMILE BORDUAS GEORGE BOWERING AA BRONSON STU BROOMER DAVID BUCHAN HANK BULL IAN BURN WILLIAM BURROUGHS JAMES LEE BYARS SARAH CHARLESWORTH VICTOR COLEMAN (VIC D'OR) MARGARET COLEMAN MICHAEL CORRIS BRUNO CORMIER JUDITH COPITHORNE COUM KATE CRAIG (LADY BRUTE) MICHAEL CRANE ROBERT CUMMING GREG CURNOE LOWELL DARLING SHARON DAVIS GRAHAM DUBÉ JEAN-MARIE DELAVALLE JAN DIBBETS IRENE DOGMATIC JOHN DOWD LORIS ESSARY ANDRÉ FARKAS GERALD FERGUSON ROBERT FILLIOU HERVÉ FISCHER MAXINE GADD WILLIAM (BILL) GAGLIONE PEGGY GALE CLAUDE GAUVREAU GENERAL IDEA DAN GRAHAM PRESTON HELLER DOUGLAS HUEBLER JOHN HEWARD DICK NO. HIGGINS MILJENKO HORVAT IMAGE BANK CAROLE ITTER RICHARDS JARDEN RAY JOHNSON MARCEL JUST PATRICK KELLY GARRY NEILL KENNEDY ROY KIYOOKA RICHARD KOSTELANETZ JOSEPH KOSUTH GARY LEE-NOVA (ART RAT) NIGEL LENDON LES LEVINE GLENN LEWIS (FLAKEY ROSE HIPS) SOL LEWITT LUCY LIPPARD STEVE 36 LOCKARD CHIP LORD MARSHALORE TIM MANCUSI DAVID MCFADDEN MARSHALL MCLUHAN ALBERT MCNAMARA A.C. MCWHORTLES ANDREW MENARD ERIC METCALFE (DR. BRUTE) MICHAEL MORRIS (MARCEL DOT & MARCEL IDEA) NANCY MOSON SCARLET MUDWYLER IAN MURRAY STUART MURRAY MAURIZIO NANNUCCI OPAL L. NATIONS ROSS NEHER AL NEIL N.E. THING CO. ALEX NEUMANN NEW YORK CORRES SPONGE DANCE SCHOOL OF VANCOUVER HONEY NOVICK (MISS HONEY) FOOTSY NUTZLE (FUTZIE) ROBIN PAGE MIMI PAIGE POEM COMPANY MEL RAMSDEN MARCIA RESNICK RESIDENTS JEAN-PAUL RIOPELLE EDWARD ROBBINS CLIVE ROBERTSON ELLISON ROBERTSON MARTHA ROSLER EVELYN ROTH DAVID RUSHTON JIMMY DE SANA WILLOUGHBY SHARP TOM SHERMAN ROBERT 460 SAINTE-CATHERINE WEST, ROOM 508, SMITHSON ROBERT STEFANOTTY FRANÇOISE SULLIVAN MAYO THOMSON FERN TIGER TESS TINKLE JASNA MONTREAL, QUEBEC H3B 1A7 TIJARDOVIC SERGE TOUSIGNANT VINCENT TRASOV (VINCENT TARASOFF & MR. -

This Part That Seemingly Needs to Get out Through

This Part That Seemingly Needs to Get Out This multiplicity of positions reinforces yet through a Place in My Body again the complex dimension of this topic and the difficulty of setting it within a rigid This exhibition is a proposal that tests its framework. But however complicated such own approach and methodology and an initiative might prove to be, it is to be accepts its own inevitably fragmentary hoped that it will draw attention to a vast nature, induced by instances of institutional social and cultural phenomenon—emigration conditioning, as well as by the intrinsic and exile during the Cold War—that is volatility of the subject. It is a reflection on a essential to an understanding of the way in phenomenon examined all too little in the which the artistic field was configured in context of Romanian contemporary art: the Romania, with an undeniable impact on how migration of Romanian artists to the West it looks today. In times of global migration, during the communist period, and focuses when mobility and human interactions unfold more closely on the late 1960s and the according to completely different 1970s. Restricting the scope of the coordinates, it is important that we examination even further, it is important to remember a period when the chance to point out that the exhibition highlights the travel abroad could completely and careers of artists active in Bucharest before irrevocably change the course of a person’s emigrating to the West at various times. life. Reactivating the memory of those Some among them are figures well known decades today becomes all the more internationally, albeit not yet fully assimilated necessary since a fast approaching into the canons of world art history. -

Mind Over Matter: Conceptual Art from the Collection

MIND OVER MATTER: CONCEPTUAL ART FROM THE COLLECTION Yoko Ono: Everson Catalog Box, 1971; wooden box (designed by George Maciunas) containing artist’s book, glass key, offset printing on paper, acrylic on canvas, and plastic boxes; 6 × 6 ¼ × 7 ¼ in.; BAMPFA, museum purchase: Bequest of Thérèse Bonney, Class of 1916, by exchange. Photo: Sibila Savage. COVER Stephen Kaltenbach: Art Works, 1968–2005; bronze; 4 ⅞ × 7 ⅞ × ⅝ in.; BAMPFA, museum purchase: Bequest of Thérèse Bonney, Class of 1916, by exchange. Photo: Benjamin Blackwell. Mind Over Matter: Conceptual Art from the Collection University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive October 19–December 23, 2016 Mind Over Matter: Conceptual Art from the Collection is organized by BAMPFA Adjunct Curator Constance M. Lewallen. The exhibition is supported in part by Alexandra Bowes and Stephen Williamson, Rena Bransten, and Robin Wright and Ian Reeves. Contents 5 Director’s Foreword LAWRENCE RINDER 7 Mind Over Matter: The Collaboration JULIA BRYAN-WILSON 8 Introduction CONSTANCE M. LEWALLEN 14 Robert Morris: Sensationalizing Masculinity in the Labyrinths-Voice-Blind Time Poster CARLOS MENDEZ 16 Stretching the Truth: Understanding Jenny Holzer’s Truisms ELLEN PONG 18 Richard Long’s A Hundred Mile Walk EMILY SZASZ 20 Conceiving Space, Creating Place DANIELLE BELANGER 22 Can Ice Make Fire? Prove or Disprove TOBIAS ROSEN 24 Re-enchantment Through Irony: Language-games, Conceptual Humors, and John Baldessari’s Blasted Allegories HAILI WANG 26 Fragments and Ruptures: Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Mouth to Mouth BYUNG KWON (B. K.) KIM 28 The Same Smile: Negotiating Masculinity in Stephen Laub’s Relations GABRIEL J. -

James Lee Byars: Sphere Is a Sphere Is a Sphere Is a Sphere 19 March – 11 June 2016

James Lee Byars: Sphere Is a Sphere Is a Sphere Is a Sphere 19 March – 11 June 2016 Peder Lund is pleased to announce an exhibition with the American artist James Lee Byars (1932-1997). Originally a student of art and philosophy at Wayne State University, Byars stated that his main influences were "Stein, Einstein, and Wittgenstein." After complet- ing his studies in the United States, Byars spent nearly a decade living in Japan where he, influenced by Zen Buddhism, Noh theatre and Shinto rituals, executed his first performances. In 1958 Byars returned to the United States and forged a relationsip with Dorothy Miller, the first curator of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. After meeting Byars, Miller allowed him to hold a temporary exhibition in the stairwell of the MoMA which was the artist's New York debut. Since then, the performative events, sculptures, drawings, installations, and wearable art of James Lee Byars has been widely exhibited internationally. Up until his death at the age of 65 Byars had remained in constant pursuit of the concept of perfection and truth. Byars shaped his persona and career into a continuous performance, when his life and art merged with each other. Ken Johnson of the New York Times described him as a "dandified hierophant." At the age of 37 Byars wrote a book titled ½ an autobiography while he sat in a gallery space noting down thoughts and questions as visitors passed through. The book was published afterwards with the additonal title The Big Sample of Byars. -

Fergus Mccaffrey Presents an Exhibition Surveying the Artistic Networks and Avant- Garde Work by American and Japanese Artists Between 1952 – 1985

Fergus McCaffrey presents an exhibition surveying the artistic networks and avant- garde work by American and Japanese artists between 1952 – 1985 Japan Is America Fergus McCaffrey New York October 30 – December 14, 2019 Fergus McCaffrey is pleased to present Japan Is America, an exhibition exploring the complex artistic networks that informed avant-garde art in Japan and America between 1952 and 1985. Starting with the well-documented emergence of “American-Style Painting” that ran parallel to the Americanization of Japan in the 1950s, Japan Is America endeavors to illustrate the path and conditions from Japanese surrender in 1945 to that country's putative cultural take-over of the United States some forty years later. The exhibition traces the international exchanges that supported and propelled Japanese art forward in unimaginable ways, and shifted the course of American art and culture. The exhibition will be accompanied by an ambitious film program including rarely-seen films by John Cage, Shigeko Kubota, and Fujiko Nakaya, among others. In the aftermath of World War II, both countries sought recognition beyond the cultural periphery, carving out a space for the redefinition of aesthetics in the post-war era. After 1945, Japan focused on rebuilding, countering the devastation of their defeat in World War II. The nation was occupied by American forces between 1945 and 1952. Sentiments of democracy and peace resonated throughout Japan, but art from the region reflected upon and responded to the death and suffering experienced. Japan Is America begins with Tatsuo Ikeda’s kinukosuri portrait of an American soldier’s wife from 1952. -

Documenta 5 Working Checklist

HARALD SZEEMANN: DOCUMENTA 5 Traveling Exhibition Checklist Please note: This is a working checklist. Dates, titles, media, and dimensions may change. Artwork ICI No. 1 Art & Language Alternate Map for Documenta (Based on Citation A) / Documenta Memorandum (Indexing), 1972 Two-sided poster produced by Art & Language in conjunction with Documenta 5; offset-printed; black-and- white 28.5 x 20 in. (72.5 x 60 cm) Poster credited to Terry Atkinson, David Bainbridge, Ian Burn, Michael Baldwin, Charles Harrison, Harold Hurrrell, Joseph Kosuth, and Mel Ramsden. ICI No. 2 Joseph Beuys aus / from Saltoarte (aka: How the Dictatorship of the Parties Can Overcome), 1975 1 bag and 3 printed elements; The bag was first issued in used by Beuys in several actions and distributed by Beuys at Documenta 5. The bag was reprinted in Spanish by CAYC, Buenos Aires, in a smaller format and distrbuted illegally. Orginally published by Galerie art intermedai, Köln, in 1971, this copy is from the French edition published by POUR. Contains one double sheet with photos from the action "Coyote," "one sheet with photos from the action "Titus / Iphigenia," and one sheet reprinting "Piece 17." 16 ! x 11 " in. (41.5 x 29 cm) ICI No. 3 Edward Ruscha Documenta 5, 1972 Poster 33 x 23 " in. (84.3 x 60 cm) ICI /Documenta 5 Checklist page 1 of 13 ICI No. 4 Lawrence Weiner A Primer, 1972 Artists' book, letterpress, black-and-white 5 # x 4 in. (14.6 x 10.5 cm) Documenta Catalogue & Guide ICI No. 5 Harald Szeemann, Arnold Bode, Karlheinz Braun, Bazon Brock, Peter Iden, Alexander Kluge, Edward Ruscha Documenta 5, 1972 Exhibition catalogue, offset-printed, black-and-white & color, featuring a screenprinted cover designed by Edward Ruscha. -

Imaging the Void: Making the Invisible Visible an Exploration Into the Function of Presence in Performance, Performative Photography and Drawing

Imaging the Void: Making the Invisible Visible An Exploration into the Function of Presence in Performance, Performative Photography and Drawing. By John Lethbridge A thesis submitted as fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of New South Wales Faculty of Art and Design June 2016 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.’ Signed ………… Date …………01 – 06 - 2016………………………………… COPYRIGHT STATEMENT ‘I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. -

LA GALERÍA CLAIRE COPLEY Y LOS INTERCAMBIOS ENTRE NORTEAMÉRICA Y EUROPA EN EL TIEMPO DEL ARTE CONCEPTUAL (1973-1977) Quintana

Quintana. Revista de Estudos do Departamento de Historia da Arte ISSN: 1579-7414 [email protected] Universidade de Santiago de Compostela España de Llano Neira, Pedro LA GALERÍA CLAIRE COPLEY Y LOS INTERCAMBIOS ENTRE NORTEAMÉRICA Y EUROPA EN EL TIEMPO DEL ARTE CONCEPTUAL (1973-1977) Quintana. Revista de Estudos do Departamento de Historia da Arte, núm. 14, 2015, pp. 159-186 Universidade de Santiago de Compostela Santiago de Compostela, España Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=65349338012 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto LA GALERÍA CLAIRE COPLEY Y LOS INTERCAMBIOS ENTRE NORTEAMÉRICA Y EUROPA EN EL TIEMPO DEL ARTE CONCEPTUAL (1973-1977) 1 Data recepción: 2014/01/23 Pedro de Llano Neira Data aceptación: 2016/01/13 Universidade de Santiago de Compostela Contacto autor: [email protected] RESUMEN La galería de Claire Copley en Los Ángeles fue un espacio que inspiró algunos de los proyectos más innovadores y vanguardistas del arte Conceptual. En un periodo de solo cuatro años, entre 1973 y 1977, Copley promovió ex- posiciones como las de Michael Asher, Bas Jan Ader o Allen Ruppersberg, que forman parte de la historia del arte reciente. Dos fueron sus objetivos principales: mostrar el trabajo de artistas locales que todavía no habían recibido la atención que ella consideraba que se merecían y crear un diálogo entre Norteamérica y Europa. -

Unconcealment Lynda Morris | 11

Unconcealment Lynda Morris | 11 Introduction | 33 Parti Support structure | 45 Chapter 1 The beginnings of the network of Conceptual artists: 1967 and earlier | 53 1.1 Seeds of the Network: 1967 | 53 Paul Maenz's inaugural exhibitions in Germany • The First Cologne Kunstmarkt • Konrad Fischer, Diisseldorf • Carl Andre • Hanne Darboven • America-West Germany connections • Sol LeWitt • Fischer's leading role • Heiner Friedrich, Munich • Arte Povera in Italy 1.2 Conclusion | 67 Technical improvements and social unrest Chapter 2 The growth of the network and temporary exhibitions: 1968-69 | 69 2.1 1968 I 69 Minimal art in Europe • Seth Siegelaub and Lucy R. Lippard • Gian Enzo Sperone, Turin • May 1968: France and Italy • 1968 Venice Biennale • Documenta 4 • Wide White Space, Antwerp • Bruce Nauman • Jan Dibbets • Richard Long • Art & Project, Amsterdam • Prospect 68 • 1968 Cologne Kunstmarkt • Arte povera e Azionepovere • Carl Andre, Stadtisches Museum, Monchengladbach • Robert Ryman • American Conceptual artists in America • Xerox Book 2.2 1969 I 86 The Rhineland area • Daniel Buren • European Conceptual artists in America • One Month • Walther Konig's bookshop, Cologne • Op Losse Schroeven and When Attitudes Become Form • Travelling shows • Lawrence Weiner • Yvon Lambert, Paris • Frangoise Lambert, Milan • A 379089, Antwerp • July-August-September ig6g and 557,08/ • Prospect 69 and the Cologne Kunstmarkt • Growth of Euro- pean art fairs • Konzeptioni'Conception • Joseph Kosuth • Dealers networking • Arte Povera, Conceptual, Actual or Impossible -

Download .Pdf

FLEX ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Douglas Walla, Katrina Neumann, Elyse Harary. Catherine Kord, Harvey LaTourette, Robert Wilhite, Calvin Tompkins, Florence Bonnefous, Air de Paris, Greene- Naftali Gallery, Gordon VeneKlasen, Michael Werner, Stephanie Chow, Lisa Overduin, Overduin & Co., Evelena Ruether, Samuel Freeman, Max Maslansky, Richard Telles, Antonio Homem, Queenie Wong, Sonnabend Gallery, Alexxa Gotthardt, Suzanne Geiss, Joan Washburn, Washburn Gallery, Dana Martin, Francis Naumann, Barbara Bertozzi Castelli, Diana Zlotnick, and Emily Weiss. A special thanks to all of the incredible artists, writers, and performers who were integral to the FLEX project. Andrea Pallaoro, Arthur Ashin, Brody Brown, Zackary Drucker, Gage Boone, Tom Campbell, Robin Newman, Roi Cydulkin, Tom Lawson, and Monique Roelofs, thank you. Published on the occasion of FLEX at Kent Fine Art LLC. Curated by Orlando Tirado September 5 — October 31, 2014 Kent Fine Art 210 Eleventh Avenue New York, NY 10001 United States www.kentfineart.net 212-365-9500 Copyright © 2014 Kent Fine Art LLC All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Edited by Orlando Tirado Transcriptions by Elyse Harary Cover Drawing by Orlando Tirado Design by Katrina Neumann Limited edition sticker insert by Carlo Quispe Limited edition poster insert by Brica Wilcox Typeset: Century Gothic, Corbel, and Stencilla Printed by Linco Printing Company Long Island City, New York RICHARD ARTSCHWAGER MATH BASS JAMES LEE BYARS 31, 2014 GUY de COINTET MARCEL DUCHAMP OCTOBER DAN FINSEL — GORDON HALL 5 MOLLY LOWE ROBERT MORRIS MYRON STOUT SEPTEMBER FLEX EXHIBITION CHECKLIST 1 Richard Artschwager. -

Performance Art Context R

Literature: Literature: (...continued) Literature: Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Kunstf. Bd.137 / Atlas der Künstlerreisen Literature: (...continued) Literature: (... continued) Richard Kostelnatz / The Theater of Crossings (catalogue) E. Jappe / Performance Ritual Prozeß Walking through society (yearbook) ! Judith Butler !! / Bodies That Matter Victoria Best & Peter Collier (Ed.) / article: Kultur als Handlung Kunstf. Bd.136 / Ästhetik des Reisens Butoh – Die Rebellion des Körpers PERFORMANCE ART CONTEXT R. Shusterman / Kunst leben – Die Ästhetik Mixed Means. An Introduction to Zeitspielräume. Performance Musik On Ritual (Performance Research) Eugenio Barber (anthropological view) Performative Acts and Gender Constitution Powerful Bodies – Performance in French Gertrude Koch Zeit – Die vierte Dimension in der (Kazuo Ohno, Carlotta Ikeda, Tatsumi des Pragmatismus Happenings, Kinetic Environments ... ! Ästhetik / Daniel Charles Richard Schechner / Future of Ritual Camille Camillieri (athropolog. view; (article 1988!) / Judith Butler Cultural Studies !! Mieke Bal (lecture) / Performance and Mary Ann Doane / Film and the bildenden Kunst Hijikata, Min Tanaka, Anzu Furukawa, Performative Approaches in Art and Science Using the Example of "Performance Art" R. Koberg / Die Kunst des Gehens Mitsutaka Ishi, Testuro Tamura, Musical Performance (book) Stan Godlovitch Kunstforum Bd. 34 / Plastik als important for Patrice Pavis) Performativity and Performance (book) ! Geoffrey Leech / Principles -

Art Review Asian Aesthetic Influences on American Artists: Guggenheim

Vol. 11, No. 1 International Journal of Multicultural Education 2009 Art Review Asian Aesthetic Influences on American Artists: Guggenheim Museum Exhibition Hwa Young Caruso, Ed. D. Art Review Editor Exhibition Highlights: Selected Artists and Works of Art Conclusion Reference During the spring of 2009, the New York City Guggenheim Museum sponsored a three-month group exhibition entitled “The Third Mind: American Artists Contemplate Asia, 1860-1989.” Alexandra Munroe, Senior Curator of Asian Art and a leading scholar who had spent three years in Japan, organized this ambitious project to display 250 works of art by 110 major American artists who had been influenced by Asian aesthetics. She selected the works because each one reflected Asian philosophy and cultural motifs and integrated intercultural experiences. This exhibition was an opportunity to validate the curator’s perspective about how Asian cultures, beliefs, and philosophies touched many American artists’ creative process of art-making over a 130- year period (Monroe, 2009). Thousands of visitors saw the exhibition, which included artworks by major American artists such as James McNeil Whistler, Mary Cassatt, Arthur Wesley Dow, Georgia O'Keefe, Alfred Stieglitz, Isamu Noguchi, Mark Tobey, David Smith, Brice Marden, John Cage, Agnes Martin, Ad Reinhardt, Robert Rauschenberg, Tehching Hsieh, Ann Hamilton, James Lee Byars, Nam June Paik, Adrian Piper, Bill Viola, and 92 others. These artists were influenced by Asian aesthetics. They used various mediums in different conceptual and stylistic approaches, which included traditional painting, drawing, printmaking, performance, video art, installation, sculpture, and photography. Each of the artists shares a common thread of being influenced by Asian culture, beliefs, intercultural experiences, or by practicing Buddhism, reflected in their art making.