University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960 Dahnya Nicole Hernandez Pitzer College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pitzer Senior Theses Pitzer Student Scholarship 2014 Funny Pages: Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960 Dahnya Nicole Hernandez Pitzer College Recommended Citation Hernandez, Dahnya Nicole, "Funny Pages: Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960" (2014). Pitzer Senior Theses. Paper 60. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pitzer_theses/60 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pitzer Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pitzer Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FUNNY PAGES COMIC STRIPS AND THE AMERICAN FAMILY, 1930-1960 BY DAHNYA HERNANDEZ-ROACH SUBMITTED TO PITZER COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE BACHELOR OF ARTS DEGREE FIRST READER: PROFESSOR BILL ANTHES SECOND READER: PROFESSOR MATTHEW DELMONT APRIL 25, 2014 0 Table of Contents Acknowledgements...........................................................................................................................................2 Introduction.........................................................................................................................................................3 Chapter One: Blondie.....................................................................................................................................18 Chapter Two: Little Orphan Annie............................................................................................................35 -

Haraway When Species Meet.Pdf

WHEN SPECIES MEET , When Species Meet Donna J. Haraway The Poetics of DNA Judith Roof The Parasite Michel Serres WHEN SPECIES MEET Donna J. Haraway Posthumanities, Volume 3 University of Minnesota Press Minneapolis London Copyright 2008 Donna J. Haraway All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by the University of Minnesota Press 111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290 Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520 http://www.upress.umn.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Haraway, Donna Jeanne. When species meet / Donna J. Haraway. p. cm. — (Posthumanities) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN: 978-0-8166-5045-3 (hc : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8166-5045-4 (hc : alk. paper) ISBN: 978-0-8166-5046-0 (pb : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8166-5046-2 (pb : alk. paper) 1. Human-animal relationships. I. Title. QL85.H37 2008 179´.3—dc22 2007029022 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer. 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii PART I. WE HAVE NEVER BEEN HUMAN 1. When Species Meet: Introductions 3 2. Value-Added Dogs and Lively Capital 45 3. Sharing Suffering: Instrumental Relations between Laboratory Animals and Their People 69 4. Examined Lives: Practices of Love and Knowledge in Purebred Dogland 95 5. -

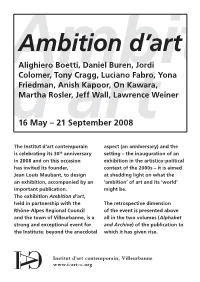

D'art Ambition D'art Alighiero Boetti, Daniel Buren, Jordi Colomer, Tony

Ambition d’art AmbitionAlighiero Boetti, Daniel Buren, Jordi Colomer, Tony Cragg, Luciano Fabro, Yona Friedman, Anish Kapoor, On Kawara, Martha Rosler, Jeff Wall, Lawrence Weiner d’art16 May – 21 September 2008 The Institut d’art contemporain aspect (an anniversary) and the is celebrating its 30th anniversary setting – the inauguration of an in 2008 and on this occasion exhibition in the artistico-political has invited its founder, context of the 2000s – it is aimed Jean Louis Maubant, to design at shedding light on what the an exhibition, accompanied by an ‘ambition’ of art and its ‘world’ important publication. might be. The exhibition Ambition d’art, held in partnership with the The retrospective dimension Rhône-Alpes Regional Council of the event is presented above and the town of Villeurbanne, is a all in the two volumes (Alphabet strong and exceptional event for and Archive) of the publication to the Institute: beyond the anecdotal which it has given rise. Institut d’art contemporain, Villeurbanne www.i-art-c.org Any feedback in the exhibition is Yona Friedman, Jordi Colomer) or less to commemorate past history because they have hardly ever been than to give present and future shown (Martha Rosler, Alighiero history more density. In fact, many Boetti, Jeff Wall). Other works have of the works shown here have already been shown at the Institut never been seen before. and now gain fresh visibility as a result of their positioning in space and their artistic company (Luciano Fabro, Daniel Buren, Martha Rosler, Ambition d’art Tony Cragg, On Kawara). For the exhibition Ambition d’art, At the two ends of the generation Jean Louis Maubant has chosen chain, invitations have been eleven artists for the eleven rooms extended to both Jordi Colomer of the Institut d’art contemporain. -

In Texas * That Going to College Is Un (ELL)

IN T E CH OIL,A STIC VOL. XVI AUSTIN, TEXAS, JANUARY, 1933 No. 5 150 Counties Report Kenley Says Four Years LETTEK County Enough in High School Corsicana Wins Conference A SPANISH CONTEST IN BOX and League Organizations to Date JEFFERSON COUNTY PERSONAL PRINCIPAL CHESTER H. KEJST- Football Over Masonic Home ITEMS -*- LEY, of San Antonio High Instructor Says Greatest Diffi Counties Not Included in List Urged to Report Now School, writes the LEAGUES, as Eight Conference B Regional Winners Declared culty Is in Securing Prop follows: er Tests for Pupils. >OUNTIES that have not RDERING plays for trial from re Good-Night Good-Will On "I was unable to attend the Writer Endorses 8-Semester Thirteenth Annual Foot- O the Loan Library service, Mrs. ported officers should do so Gridiron Writer Implies ball State Championship sea T AST spring I was director Kahat Baker, of Carthage, gives some League breakfast at Ft. Worth, And One-Year Transfer Rule at once, if election has already so I have just read with interest son under the auspices of the ^-* for Spanish in Jefferson account of herself since she was a ;aken place. In many counties AIUS SHAVER in Colliers County and wrote you for sug participant in Interscholastic League ;he account of the discussion on TF the high schools of the state University Interscholastic nstitutes have not yet been held (Nov. 18) says Bob Hall, gestions for conducting the herself: :he transfer and the 8 semester will stick by the one-year League closed with the game be Last year our and in some other counties in former Masonic Home (Fort affair. -

Rforty Second Legislatlire Is Adourned

t 'v &iavhn.r ta& i .juV-- i ... h:-:- Xk v. HB Ijr;" 1 v i i .i-- ,j." Af,i, ? t syiHft ? f Big Spring Datlg Herald '.pS-N- O. 308 EIGHTEEN PAGES TODAY BIG SPRING, TEXAg, SUNDAy MORNING, MAY 24, 1031. MEMBER OF THE ASSOCIATED j It. rForty Second Legislat Is Adourned lire 4 i u. Chicago Hostess GrandsorfOf Girl'sMother Ruth Nichohj Society Sportswoman of the Air, " Special Tax I yrW&Sr"' ifiM5g HOME 4 Holder of Many Records, To Try for Ocean Hop Garfield Is . Leads Mob To Bills Among "...TOWN Shc Has Flown FaBlcr, il-- A LK Fatally'Sliot Missouri Jail . Higher Than Any Passed Other Woman Those k ByBgDDY Was Identified Auti- - Offers To Hang Negro Wi (Editor's Notet This Is the first iInny Measures KUI$lt Prohibition Organi-- ' With Own Hands; Man ot a series of five articles tracing wmmm w Dollworm Measure Is "Well. well. We have a nice,, To-- - zntion Attempted Attack daring Ruth Nichols' career from j ' s im y Illcommunlcatlon t hand. xou debutante to premier blrdwoman) Unsigned ,v Itpow, we never could understand i CLEVELAND, May 23 W RICHMOND, Mlnsnurl, May 23 why a person writing something to BliiiHaV I AUSTIN. May 23 UP) The forty-seco- nd " John N aarfleld, 29, grandson of (T1 A mob of 100 men waa dis- IhVpaor would not sign his or her Ily RICHARD MASSOCK -- legislature adjourned A. Garfield, died persed early tdday without vio at hamp to the article Tills one U President James NEW YORK, May 23. CP-It- ulh p. -

Dick Tracy.” MAX ALLAN COLLINS —Scoop the DICK COMPLETE DICK ® TRACY TRACY

$39.99 “The period covered in this volume is arguably one of the strongest in the Gould/Tracy canon, (Different in Canada) and undeniably the cartoonist’s best work since 1952's Crewy Lou continuity. “One of the best things to happen to the Brutality by both the good and bad guys is as strong and disturbing as ever…” comic market in the last few years was IDW’s decision to publish The Complete from the Introduction by Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy.” MAX ALLAN COLLINS —Scoop THE DICK COMPLETE DICK ® TRACY TRACY NEARLY 550 SEQUENTIAL COMICS OCTOBER 1954 In Volume Sixteen—reprinting strips from October 25, 1954 THROUGH through May 13, 1956—Chester Gould presents an amazing MAY 1956 Chester Gould (1900–1985) was born in Pawnee, Oklahoma. number of memorable characters: grotesques such as the He attended Oklahoma A&M (now Oklahoma State murderous Rughead and a 467-lb. killer named Oodles, University) before transferring to Northwestern University in health faddist George Ozone and his wild boys named Neki Chicago, from which he was graduated in 1923. He produced and Hokey, the despicable "Nothing" Yonson, and the amoral the minor comic strips Fillum Fables and The Radio Catts teenager Joe Period. He then introduces nightclub photog- before striking it big with Dick Tracy in 1931. Originally titled Plainclothes Tracy, the rechristened strip became one of turned policewoman Lizz, at a time when women on the the most successful and lauded comic strips of all time, as well force were still a rarity. Plus for the first time Gould brings as a media and merchandising sensation. -

75 Years of Blondie

Special Collections presents October 1 – October 31, 2005 On Display in the Exhibit Gallery Second Floor Smathers Library (East) George A. Smathers Libraries University of Florida The Early Years ON SEPTEMBER 8, 2005, THE COMIC STRIP Although the comic strip is seventy-fi ve years old, Blondie celebrated its 75th anniversary. Created by Blondie and Dagwood have only been married for Murat Bernard “Chic” Young (1901-1973), Blondie seventy-three of those years. Blondie had many is one of the longest running newspaper strips. suitors, but her early leading man was Hiho. Hiho Young produced Blondie seven days a week until Hennepin was a shorter prototype of Dagwood his death, at which time right down to the trademark his son, Dean Young, as- bow tie they both sport. sumed creative control of Young fazed out Hiho the comic strip. shortly after Blondie’s marriage to his taller and This exhibit commemo- richer rival. rates Blondie’s anniver- sary by exploring its early Dagwood was introduced history. Few realize or in 1933 as the rich play- remember that Blondie’s boy and son of railroad origins are in the genre tycoon J. Bollinger of fl apper strips that were Bumstead. Blondie had popular in the twen- Above: Hiho courted Blondie from 1930 to 1933, without success. to make a choice between ties and thirties. Prior Bottom Right: This early example of Dagwood’s classic food balancing the ne’er-do-well Hiho and to Blondie, Chic Young technique shows how he is visually distinguishable from Hiho only by Dagwood’s millions. -

A Character Presentation from © Moomin Characters™

a character presentation from © Moomin Characters™ Moomin is created by the Finnish artist and author Tove Jansson in 1945, and the books have been translated into more than 40 languages. The Moomin books make up an extraordinary collection of artwork, from expressive pen and ink drawings in the novels to explosively colourful illustrations in the picture books. Thousands of comic strip illustrations complete the collection, making it a tremendous source of inspiration and material for design. A TV animation is sold to 140 countries. A new movie animation is launched in 2014. Tove Jansson 100 years - 2014. © Apple Corps Ltd, a Beatles™ product. The Beatles is the most successful phenomenon in the music history with sales of more than 1,5 billion records. The group is still selling huge, more than forty years after the break-up. There are more than 200 licensees all over the world producing many different products, and the artwork consists of thousands of photos, graphics, album covers and logotypes from the merry sixties. © 2012 King Features Syndicate, Inc/Fleischer Studios Inc. ™ Hearst Holdings, INC. /Fleischer Studios, Inc. www.bettyboop.com Betty Boop is the first sex symbol of the silver screen, created by Max Fleischer in the early thirties. She has turned out to be an American cult icon, —a forever young Diva. Her popularity is still huge, with one of the biggest licensing programs worldwide for a variety of products. The artwork is divided into many themes and emotions. In 2012 the cosmetic company Lancôme is using the Betty Boop character in a worlwide campaign. -

It's Garfield's World, We Just Live in It

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Fall 2019 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Fall 2019 It’s Garfield’s World, We Just Live in It: An Exploration of Garfield the Cat as Icon, Money Maker, and Beast Iris B. Engel Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_f2019 Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, Animal Studies Commons, Arts Management Commons, Business Intelligence Commons, Commercial Law Commons, Contemporary Art Commons, Economics Commons, Finance and Financial Management Commons, Folklore Commons, Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, Operations and Supply Chain Management Commons, Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons, Social Media Commons, Strategic Management Policy Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Engel, Iris B., "It’s Garfield’s World, We Just Live in It: An Exploration of Garfield the Cat as Icon, Money Maker, and Beast" (2019). Senior Projects Fall 2019. 3. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_f2019/3 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -

November 23Rd, 2010 Gene Beery

Gene Beery at Algus Greenspon Within Gene Beery’s conceptual language-based paintings, there always seems to be some kind of joke—and not always one that the viewer is in on. Among the pieces included in the artist’s 50-year retrospective was Note (1970), in which the words “NOTE: MAKE A PAINTING OF A NOTE AS A PAINTING” are rendered in puffy, candy-colored letters on a pale background with a black framelike border. In another, the words “life without a sound sense of tra can seem like an incomprehensible nup” (1994) are written in black capital letters on white; the canvas is divided by a thick black line, which cuts through the lines of text so that the reversed words “art” and “pun” are separated from the rest. Gene Beery, Note, 1970, acrylic on canvas, 34 x 42 inches. The exhibition began with works from the late 1950s, when Beery, then employed as a guard at the Museum of Modern Art, was “discovered” by James Rosenquist and Sol LeWitt. An “artist’s artist,” he was championed by artists who were, and would remain, better known than he. After a 1963 show at Alexander Iolas Gallery in New York, Beery moved to the Sierra Nevada mountains, where he still lives. While other artists using text and numbers who emerged in the 1960s—Lawrence Weiner, Joseph Kosuth, On Kawara, for example—produced mostly cerebral works lacking evidence of the artist’s hand, Beery seemingly poked fun at the high Conceptualism of the day. He continued to make his uniquely homespun and humorously irreverent canvases, the rawness of their execution a throwback to the Abstract Expressionists. -

French Animation History Ebook

FRENCH ANIMATION HISTORY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Richard Neupert | 224 pages | 03 Mar 2014 | John Wiley & Sons Inc | 9781118798768 | English | New York, United States French Animation History PDF Book Messmer directed and animated more than Felix cartoons in the years through This article needs additional citations for verification. The Betty Boop cartoons were stripped of sexual innuendo and her skimpy dresses, and she became more family-friendly. A French-language version was released in Mittens the railway cat blissfully wanders around a model train set. Mat marked it as to-read Sep 05, Just a moment while we sign you in to your Goodreads account. In , Max Fleischer invented the rotoscope patented in to streamline the frame-by-frame copying process - it was a device used to overlay drawings on live-action film. First Animated Feature: The little-known but pioneering, oldest-surviving feature-length animated film that can be verified with puppet, paper cut-out silhouette animation techniques and color tinting was released by German film-maker and avante-garde artist Lotte Reiniger, The Adventures of Prince Achmed aka Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed , Germ. Books 10 Acclaimed French-Canadian Writers. Rating details. Dave and Max Fleischer, in an agreement with Paramount and DC Comics, also produced a series of seventeen expensive Superman cartoons in the early s. Box Office Mojo. The songs in the series ranged from contemporary tunes to old-time favorites. He goes with his fox terrier Milou to the waterfront to look for a story, and finds an old merchant ship named the Karaboudjan. The Fleischers launched a new series from to called Talkartoons that featured their smart-talking, singing dog-like character named Bimbo. -

Download Transcript (PDF)

KAWARA: EXHIBITION OVERVIEW Jeffrey Weiss: On Kawara was a key figure in the art of the 1960s in particular. He began working in Japan and continued work in many other cities, finally settling in New York in the mid-’60s, where he was part of the community of Conceptual art during that period of time. He knew a lot of artists that we associate with Conceptualism including Sol LeWitt and Hanne Darboven, Joseph Kosuth and Dan Graham. It’s easy to associate his work, then, with the rise of Conceptualism, although Kawara’s work, when you examine it closely, stands well apart. This exhibition was organized in cooperation with the artist. And I really wanted to show every category of Kawara’s production since around 1964. We don’t call it a retrospective because Kawara’s work is based on time, on the passage of time. So the idea of the retrospective actually doesn’t apply in the conventional sense. Anne Wheeler: We heard from a number of his friends and colleagues from even years ago that it had always been his dream to have a show at the Guggenheim because of the cyclical nature of time and the way that the building represents that in the way that you can move throughout the chronology of his work. In organizing the show we are moving more or less chronologically through the series of his works, starting in the High Gallery with works from 1963 to ’65. Jeffrey Weiss: We’re also showing Paris–New York Drawings, which he produced in Paris and New York, where he was living—both places.