Consumption, Consumerism, and Japanese Modernity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estudo E Desenvolvimento Do Jogo Karuchā Ships Invaders

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS EXATAS E DA TERRA DEPARTAMENTO DE INFORMÁTICA E MATEMÁTICA APLICADA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM SISTEMAS E COMPUTAÇÃO MESTRADO ACADÊMICO EM SISTEMAS E COMPUTAÇÃO Aprendizagem da Língua Japonesa Apoiada por Ferramentas Computacionais: Estudo e Desenvolvimento do Jogo Karuchā Ships Invaders Juvane Nunes Marciano Natal-RN Fevereiro de 2014 Juvane Nunes Marciano Aprendizagem da Língua Japonesa Apoiada por Ferramentas Computacionais: Estudo e Desenvolvimento do Jogo Karuchā Ships Invaders Dissertação de Mestrado apresentado ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Sistemas e Computação do Departamento de Informática e Matemática Aplicada da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte como requisito final para a obtenção do grau de Mestre em Sistemas e Computação. Linha de pesquisa: Engenharia de Software Orientador Prof. Dr. Leonardo Cunha de Miranda PPGSC – PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM SISTEMAS E COMPUTAÇÃO DIMAP – DEPARTAMENTO DE INFORMÁTICA E MATEMÁTICA APLICADA CCET – CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS EXATAS E DA TERRA UFRN – UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE Natal-RN Fevereiro de 2014 UFRN / Biblioteca Central Zila Mamede Catalogação da Publicação na Fonte Marciano, Juvane Nunes. Aprendizagem da língua japonesa apoiada por ferramentas computacionais: estudo e desenvolvimento do jogo Karuchā Ships Invaders. / Juvane Nunes Marciano. – Natal, RN, 2014. 140 f.: il. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Leonardo Cunha de Miranda. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte. Centro de Ciências Exatas e da Terra. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Sistemas e Computação. 1. Informática na educação – Dissertação. 2. Interação humano- computador - Dissertação. 3. Jogo educacional - Dissertação. 4. Kanas – Dissertação. 5. Hiragana – Dissertação. 6. Roma-ji – Dissertação. -

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907)

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 BuYun Chen All rights reserved ABSTRACT Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen During the Tang dynasty, an increased capacity for change created a new value system predicated on the accumulation of wealth and the obsolescence of things that is best understood as fashion. Increased wealth among Tang elites was paralleled by a greater investment in clothes, which imbued clothes with new meaning. Intellectuals, who viewed heightened commercial activity and social mobility as symptomatic of an unstable society, found such profound changes in the vestimentary landscape unsettling. For them, a range of troubling developments, including crisis in the central government, deep suspicion of the newly empowered military and professional class, and anxiety about waste and obsolescence were all subsumed under the trope of fashionable dressing. The clamor of these intellectuals about the widespread desire to be “current” reveals the significant space fashion inhabited in the empire – a space that was repeatedly gendered female. This dissertation considers fashion as a system of social practices that is governed by material relations – a system that is also embroiled in the politics of the gendered self and the body. I demonstrate that this notion of fashion is the best way to understand the process through which competition for status and self-identification among elites gradually broke away from the imperial court and its system of official ranks. -

Identification of Asian Garments in Small Museums

AN ABSTRACTOF THE THESIS OF Alison E. Kondo for the degree ofMaster ofScience in Apparel Interiors, Housing and Merchandising presented on June 7, 2000. Title: Identification ofAsian Garments in Small Museums. Redacted for privacy Abstract approved: Elaine Pedersen The frequent misidentification ofAsian garments in small museum collections indicated the need for a garment identification system specifically for use in differentiating the various forms ofAsian clothing. The decision tree system proposed in this thesis is intended to provide an instrument to distinguish the clothing styles ofJapan, China, Korea, Tibet, and northern Nepal which are found most frequently in museum clothing collections. The first step ofthe decision tree uses the shape ofthe neckline to distinguish the garment's country oforigin. The second step ofthe decision tree uses the sleeve shape to determine factors such as the gender and marital status ofthe wearer, and the formality level ofthe garment. The decision tree instrument was tested with a sample population of 10 undergraduates representing volunteer docents and 4 graduate students representing curators ofa small museum. The subjects were asked to determine the country oforigin, the original wearer's gender and marital status, and the garment's formality and function, as appropriate. The test was successful in identifying the country oforigin ofall 12 Asian garments and had less successful results for the remaining variables. Copyright by Alison E. Kondo June 7, 2000 All rights Reserved Identification ofAsian Garments in Small Museums by Alison E. Kondo A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master ofScience Presented June 7, 2000 Commencement June 2001 Master of Science thesis ofAlison E. -

Shigisan Engi Shigisan Engi Overview

Shigisan engi Shigisan engi Overview I. The Shigisan engi or Legends of the Temple on Mount Shigi consists of three handscrolls. Scroll 1 is commonly called “The Flying Granary,” Scroll 2 “The Exorcism of the Engi Emperor,” and Scroll 3 “The Story of the Nun.” These scrolls are a pictorial presentation of three legends handed down among the common people. These legends appear under the title “Shinano no kuni no hijiri no koto” (The Sage of Shinano Province) in both the Uji sh¯ui monogatari (Tales from Uji) and the Umezawa version of the Kohon setsuwash¯u (Collection of Ancient Legends). Since these two versions of the legends are quite similar, one is assumed to be based on the other. The Kohon setsuwash¯u ver- sion is written largely in kana, the phonetic script, with few Chinese characters and is very close to the text of the Shigisan engi handscrolls. Thus, it seems likely that there is a deep connection between the Shigisan engi and the Kohon setsuwash¯u; one was probably the basis for the other. “The Flying Granary,” Scroll 1 of the Shigisan engi, lacks the textual portion, which has probably been lost. As that suggests, the Shigisan engi have not come down to us in their original form. The Shigisan Ch¯ogosonshiji Temple owns the Shigisan engi, and the lid of the box in which the scrolls were stored lists two other documents, the Taishigun no maki (Army of Prince Sh¯otoku-taishi) and notes to that scroll, in addition to the titles of the three scrolls. -

Artful Adventures JAPAN an Interactive Guide for Families 56

Artful Adventures JAPAN An interactive guide for families 56 Your Japanese Adventure Awaits You! f See inside for details JAPAN Japan is a country located on the other side of the world from the United States. It is a group of islands, called an archipelago. Japan is a very old country and the Japanese people have been making beautiful artwork for thousands of years. Today we are going to look at ancient objects from Japan as well as more recent works of Japanese art. Go down the stairs to the lower level of the Museum. At the bottom of the steps, turn left and walk through the Chinese gallery to the Japanese gallery. Find a clay pot with swirling patterns on it (see picture to the left). This pot was made between 2,500 and 1,000 b.c., during the Late Jōmon period—it is between 3,000 and 4,500 years old! The people who lived in Japan at this time were hunter-gatherers, which means that they hunted wild animals and gathered roots and plants for food. The Jomon people started forming small communities, and began to make objects that were both beautiful and useful— like this pot which is decorated with an interesting pattern and was used for storage. Take a close look at the designs on this pot. Can you think of some words to describe these designs? Japanese, Middle to Late Jōmon period, ca. 3500–ca. 1000 B.C.: jar. Earthenware, h. 26.0 cm. 1. ............................................................................................................. Museum purchase, Fowler McCormick, Class of 1921, Fund (2002-297). -

The Selected Poems of Yosa Buson, a Translation Allan Persinger University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2013 Foxfire: the Selected Poems of Yosa Buson, a Translation Allan Persinger University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Persinger, Allan, "Foxfire: the Selected Poems of Yosa Buson, a Translation" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 748. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/748 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOXFIRE: THE SELECTED POEMS OF YOSA BUSON A TRANSLATION By Allan Persinger A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2013 ABSTRACT FOXFIRE: THE SELECTED POEMS OF YOSA BUSON A TRANSLATION By Allan Persinger The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2013 Under the Supervision of Professor Kimberly M. Blaeser My dissertation is a creative translation from Japanese into English of the poetry of Yosa Buson, an 18th century (1716 – 1783) poet. Buson is considered to be one of the most important of the Edo Era poets and is still influential in modern Japanese literature. By taking account of Japanese culture, identity and aesthetics the dissertation project bridges the gap between American and Japanese poetics, while at the same time revealing the complexity of thought in Buson's poetry and bringing the target audience closer to the text of a powerful and mov- ing writer. -

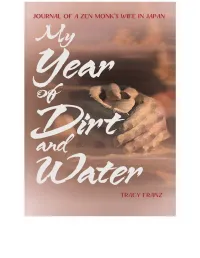

My Year of Dirt and Water

“In a year apart from everyone she loves, Tracy Franz reconciles her feelings of loneliness and displacement into acceptance and trust. Keenly observed and lyrically told, her journal takes us deep into the spirit of Zen, where every place you stand is the monastery.” KAREN MAEZEN MILLER, author of Paradise in Plain Sight: Lessons from a Zen Garden “Crisp, glittering, deep, and probing.” DAI-EN BENNAGE, translator of Zen Seeds “Tracy Franz’s My Year of Dirt and Water is both bold and quietly elegant in form and insight, and spacious enough for many striking paradoxes: the intimacy that arises in the midst of loneliness, finding belonging in exile, discovering real freedom on a journey punctuated by encounters with dark and cruel men, and moving forward into the unknown to finally excavate secrets of the past. It is a long poem, a string of koans and startling encounters, a clear dream of transmissions beyond words. And it is a remarkable love story that moved me to tears.” BONNIE NADZAM, author of Lamb and Lions, co-author of Love in the Anthropocene “A remarkable account of a woman’s sojourn, largely in Japan, while her husband undergoes a year-long training session in a Zen Buddhist monastery. Difficult, disciplined, and interesting as the husband’s training toward becoming a monk may be, it is the author’s tale that has our attention here.” JOHN KEEBLE, author of seven books, including The Shadows of Owls “Franz matches restraint with reflexiveness, crafting a narrative equally filled with the luminous particular and the telling omission. -

Kokawadera Engi Kokawadera Engi Overview

Kokawadera engi Kokawadera engi Overview the Kokawadera engi emaki. We can assume its content from I. the kanbun account, the Kokawadera engi. The Kokawadera engi emaki (Illustrated Scroll of the II. Legends of the Kokawadera Temple) is a set of colored pic- tures on paper compiled into one scroll and consists of four The synopsis of the Engi is as follows. The Kokawadera text sections and five pictures. The beginning of the scroll Temple was founded in the first year of H¯oki. According to was burned in a fire, and the first pages of the remaining part the tradition of the elders, there was a hunter in this area, are badly scorched as well. Neither the authors nor the time named Otomo¯ no Kujiko. Devoting himself to hunting, Kujiko of production is known but it is considered to be a work of lived in the mountains and shot at game every night from a the early Kamakura period. The style of painting resembles platform he built in a valley. One night he saw a shining light, that of the Shigisan engi emaki. about the size of a large sedge hat. Frightened, Kujiko The Kokawadera Temple is an old temple in Wakayama stepped down from the platform and went near the light, but Prefecture, that, according to legend, a local hunter, Otomo¯ the light was gone. Yet when he went back to the platform, no Kujiko, built it in the first year of H¯oki (770). It is well the light began to shine again. This continued to happen for known as the fourth site of the Saikoku thirty-three temple three or four nights, so he cleaned the area, built a hut with pilgrimage circuit. -

ISSN# 1203-9017 Summer 2011, Vol.16, No.2

The Royal Visit of 1939 JCNM 2010.80.2.66 ISSN# 1203-9017 Summer 2011, Vol.16, No.2 The Royal Visit of 1939 by Bryan Akazawa 2 Building Community Partnerships by Beth Carter 3 A Visit to Mio Village and its Canada Immigration Museum by Stan Fukawa 4 World War II and Kika-nisei by Haruji (Harry) Mizuta 6 Two Unusual Artifacts! 11 From Kaslo to New Denver – A Road Trip by Carl Yokota 12 One Big Hapa Family by Christine Kondo 14 Jinzaburo Oikawa Descendents Survive Earthquake and Tsunami by Stan Fukawa 15 Growing Up on Salt Spring Island by Raymond Nakamura 16 “Just Add Shoyu” review by Margaret Lyons 20 Forever the Vancouver ASAHI Baseball Team! by Norifumi Kawahara 21 The Postwar M.A. Berry Growers Co-op by Stan Fukawa 22 Treasures from the Collections 24 CONTENTS ON THE COVER: The Royal Visit of 1939 by Bryan Akazawa he recent Canadian tour of William and Catherine, the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge, is a mirror image of the visit of Prince William’s great grandfather King George VI back in 1939. In both cases there was T a real concerted effort to strengthen ties between Canada and Britain, to increase and solidify bonds of trust and loyalty. During their visit, King George VI and his wife, Queen Elizabeth travelled 80 km by motorcade through the streets of Vancouver, including Powell Street. The Royal Couple was greeted by the proud and excited Japanese Canadian resi- dents. The community members were dressed in their finest clothing and elaborate kimono. -

Japanese Costume

JAPANESE COSTUME BY HELEN C. GUNSAULUS Assistant Curator of Japanese Ethnology FIELD MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CHICAGO 1923 Field Museum of Natural History DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY Chicago, 1923 Leaflet Number 12 Japanese Costume Though European influence is strongly marked in many of the costumes seen today in the larger sea- coast cities of Japan, there is fortunately little change to be noted in the dress of the people of the interior, even the old court costumes are worn at a few formal functions and ceremonies in the palace. From the careful scrutinizing of certain prints, particularly those known as surimono, a good idea may be gained of the appearance of all classes of people prior to the in- troduction of foreign civilization. A special selection of these prints (Series II), chosen with this idea in mind, may be viewed each year in Field Museum in Gunsaulus Hall (Room 30, Second Floor) from April 1st to July 1st at which time it is succeeded by another selection. Since surimono were cards of greeting exchanged by the more highly educated classes of Japan, many times the figures portrayed are those known through the history and literature of the country, and as such they show forth the costumes worn by historical char- acters whose lives date back several centuries. Scenes from daily life during the years between 1760 and 1860, that period just preceding the opening up of the coun- try when surimono had their vogue, also decorate these cards and thus depict the garments worn by the great middle class and the military ( samurai ) class, the ma- jority of whose descendents still cling to the national costume. -

Types of Japanese Folktales

Types of Japanese Folktales By K e ig o Se k i CONTENTS Preface ............................................................................ 2 Bibliography ................................... ................................ 8 I. Origin of Animals. No. 1-30 .....................................15 II. A nim al Tales. No. 31-74............................................... 24 III. Man and A n im a l............................................................ 45 A. Escape from Ogre. No. 75-88 ....................... 43 B. Stupid Animals. No. 87-118 ........................... 4& C. Grateful Animals. No. 119-132 ..................... 63 IV. Supernatural Wifes and Husbands ............................. 69 A. Supernatural Husbands. No. 133-140 .............. 69 B. Supernatural Wifes. No. 141-150 .................. 74 V. Supernatural Birth. No. 151-165 ............................. 80 VI. Man and Waterspirit. No. 166-170 ......................... 87 VII. Magic Objects. No. 171-182 ......................................... 90 V III. Tales of Fate. No. 183-188 ............................... :.… 95 IX. Human Marriage. No. 189-200 ................................. 100 X. Acquisition of Riches. No. 201-209 ........................ 105 X I. Conflicts ............................................................................I l l A. Parent and Child. No. 210-223 ..................... I l l B. Brothers (or Sisters). No. 224-233 ..............11? C. Neighbors. No. 234-253 .....................................123 X II. The Clever Man. No. 254-262 -

Tradisi Pemakaian Geta Dalam Kehidupan Masyarakat Jepang Nihon Shakai No Seikatsu Ni Okeru Geta No Haki Kanshuu

TRADISI PEMAKAIAN GETA DALAM KEHIDUPAN MASYARAKAT JEPANG NIHON SHAKAI NO SEIKATSU NI OKERU GETA NO HAKI KANSHUU SKRIPSI Skripsi Ini Diajukan Kepada Panitia Ujian Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Sumatera Utara Medan Untuk Melengkapi salah Satu Syarat Ujian Sarjana Dalam Bidang Ilmu Sastra Jepang Oleh: AYU PRANATA SARAGIH 120708064 DEPARTEMEN SASTRA JEPANG FAKULTAS ILMU BUDAYA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2016 i Universitas Sumatera Utara TRADISI PEMAKAIAN GETA DALAM KEHIDUPAN MASYARAKAT JEPANG NIHON SHAKAI NO SEIKATSU NI OKERU GETA NO HAKI KANSHUU SKRIPSI Skripsi Ini Diajukan Kepada Panitia Ujian Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Sumatera Utara Medan Untuk Melengkapi salah Satu Syarat Ujian Sarjana Dalam Bidang Ilmu Sastra Jepang Oleh: AYU PRANATA SARAGIH 120708064 Pembimbing I Pembimbing II Dr. Diah Syafitri Handayani, M.Litt Prof. Hamzon Situmorang,M.S, Ph.D NIP:19721228 1999 03 2 001 NIP:19580704 1984 12 1 001 DEPARTEMEN SASTRA JEPANG FAKULTAS ILMU BUDAYA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2016 ii Universitas Sumatera Utara Disetujui Oleh, Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Sumatera Utara Medan Medan, September 2016 Departemen Sastra Jepang Ketua, Drs. Eman Kusdiyana, M.Hum NIP : 196009191988031001 iii Universitas Sumatera Utara KATA PENGANTAR Segala puji dan syukur penulis panjatkan kepada Tuhan Yesus Kristus, oleh karena kasih karunia-Nya yang melimpah, anugerah,dan berkat-Nya yang luar biasa akhirnya penulis dapat menyelesaikan skripsi ini. Penulis dapat menyelesaikan skripsi ini yang merupakan syarat untuk mencapai gelar sarjana di Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Sumatera Utara. Adapun skripsi ini berjudul “Tradisi Pemakaian Geta Dalam Kehidupan Masyarakat Jepang”. Skripsi ini penulis persembahkan kepada orang tua penulis, Ibu Sonti Hutauruk, mama terbaik dan terhebat yang dengan tulus ikhlas memberikan kasih sayang, doa, perhatian, nasihat, dukungan moral dan materil kepada penulis sehingga penulis dapat menyelesaikan studi di Sastra Jepang USU, khususnya menyelesaikan skripsi ini.