South Tyrol a Usage That May Reveal a Pro- Tyrolean Prejudice, Or Merely Convenience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jahre | Anni | Years

JAHRE | ANNI | YEARS GRANPANORAMAHOTEL 2019 GRANPANORAMAHOTEL Willkommen Dank der schönen Panoramalage auf dem Sonnenplateau von Villanders, zeigen sich unsere Gäste immer wieder überwältigt vom einmaligen Ausblick auf die Dolomiten, der sich von jedem unserer Zimmer aus genießen lässt. Benvenuti Grazie alla nostra posizione panoramica sull’altopiano soleggiato di Villandro, i nostri ospiti beneficiano di una vista spet- tacolare sulle Dolomiti – da ogni stanza del nostro hotel. Welcome Due to our excellent position on the sun- drenched Villandro plateau, our guests are always overwhelmed by the unique view of the Dolomites, which they can enjoy from each of our rooms. GRANPANORAMAHOTEL Südtiroler Hochgenuss Himmlischer Genuss vor der Traumkulisse der Dolomiten. Das erwartet Sie im Granpanorama Hotel StephansHof. Puro piacere tirolese Piaceri divini sullo sfondo incantevole delle Dolomiti. Ecco cosa Vi attende al Granpanorama Hotel StephansHof. South Tyrolean delight Heavenly delights against the backdrop of the Dolomites. This is what awaits you at the Granpanorama Hotel StephansHof! GRANPANORAMAHOTEL Im Herzen Südtirols Nel cuore dell’Alto Adige In the heart of South Tyrol GRANPANORAMAHOTEL Der geographische Mittelpunkt Südtirols liegt in der Gemeinde Villanders. Das Granpanorama Hotel StephansHof liegt daher mitten im Herzen Südtirols und ist so der perfekte Ausgangspunkt für Ihren Urlaub in Südtirol. Hier entdecken Sie das ganze Land mit seinen Städten und Kulturzentren von einem einzigen Punkt aus. Il centro geografico dell’Alto Adige si trova nel comune di Villandro. Di conseguenza, il Granpanorama Hotel StephansHof si trova nel pieno cuore dell’Alto Adige ed è il punto di partenza ideale per le Vostre vacanze in Alto Adige. Da qui potrete partire alla scoperta dell’intera regione, alla volta delle sue città e dei suoi centri culturali. -

Entdecke Mit Mir Das Eisacktal Scopri Con Me La Valle Isarco Let’S Explore the Eisacktal Valley 2 Pfeifer Huisele

Entdecke mit mir das Eisacktal Scopri con me la Valle Isarco Let’s explore the Eisacktal Valley 2 Pfeifer Huisele Sobald Pfeifer Huisele auftaucht, herrscht Aufregung. Die in Ratschings beheimatete Sagengestalt konnte sich als Zauberer in jedes Wesen verwandeln, egal ob Fliege oder Elefant. Er wurde gefürchtet und als Hexen- meister bezeichnet. Als solcher verursachte er Unwetter und andere Katastrophen, bis der Teufel dem Treiben ein Ende setzte. Heute führt er dich durch das Eisacktal. Action, Spaß und Spannung sind angesagt. Der positive Nebeneffekt: Du lernst ganz nebenbei, was das Eisack- tal an Geschichtlichem, Kulturellem und Kulinarischem zu bieten hat! Non appena arriva Pfeifer Huisele, l’eccitazione è garan- tita. Come mago si poteva trasformare in tutto ciò che voleva, non importa se mosca o elefante. Tutti tenevano paura di lui e veniva chiamato stregone. Come tale cau- sava temporali e altre catastrofi, finché il diavolo non ha posto fine a tutto questo. In tempi passati infestava suo luogo, ma oggi ti accompagna attraverso tutta la Valle Isarco. Azione, divertimento e curiosità sono garantiti. Impara cosa offre la Valle Isarco per quanto riguarda storia, cultura e cucina! 3 Talking about the Pfeifer Huisele causes excitement. As a wizard this fi gure was able to turn into any imaginable character, no matter if elephant or fl y. He was feared by people and was called warlock. He was responsible for storms and other disasters until the devil put an end to it. In the past the Pfeiff er Huisele was making trouble but nowadays he is the one to lead you through the Eisack- tal valley. -

The North-South Divide in Italy: Reality Or Perception?

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk EUROPEAN SPATIAL RESEARCH AND POLICY Volume 25 2018 Number 1 http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/1231-1952.25.1.03 Dario MUSOLINO∗ THE NORTH-SOUTH DIVIDE IN ITALY: REALITY OR PERCEPTION? Abstract. Although the literature about the objective socio-economic characteristics of the Italian North- South divide is wide and exhaustive, the question of how it is perceived is much less investigated and studied. Moreover, the consistency between the reality and the perception of the North-South divide is completely unexplored. The paper presents and discusses some relevant analyses on this issue, using the findings of a research study on the stated locational preferences of entrepreneurs in Italy. Its ultimate aim, therefore, is to suggest a new approach to the analysis of the macro-regional development gaps. What emerges from these analyses is that the perception of the North-South divide is not consistent with its objective economic characteristics. One of these inconsistencies concerns the width of the ‘per- ception gap’, which is bigger than the ‘reality gap’. Another inconsistency concerns how entrepreneurs perceive in their mental maps regions and provinces in Northern and Southern Italy. The impression is that Italian entrepreneurs have a stereotyped, much too negative, image of Southern Italy, almost a ‘wall in the head’, as also can be observed in the German case (with respect to the East-West divide). Keywords: North-South divide, stated locational preferences, perception, image. 1. INTRODUCTION The North-South divide1 is probably the most known and most persistent charac- teristic of the Italian economic geography. -

The Isel Flows Through East Tyrol from the Icy Heights of the Glaciers in the Hohe Tauern to the Sunny District Capital Lienz in the Southeast

ISEL • 2020 W. Retter © Picture: The Isel flows through East Tyrol from the icy heights of the glaciers in the Hohe Tauern to the sunny district capital Lienz in the southeast. Nothing but the forces of nature influence the dynamics of the East The Isel with ist tributaries is an Tyrolean heart river. Almost unaffected by congestion, diversions or internationally unique treasure trove of surges, the Isel flows from its source to its mouth. On its journey nature and provides habitat for several glacial streams of the Tyrolean National Park Hohe Tauern endangered animal and plant species. unite in the Isel. About 4 percent of the catchment area or 50 square From the source to the mouth, the Isel kilometers are glaciated. The meltwater has a major influence on the may still flow freely, almost unimpeded Isel during the course of the day and year: in summer the river carries by congestion, diversion or surge. up to twenty times more water than in winter. On warm summer afternoons, the rock contained in the glacier water, finely crushed by Profile Origin: at 2 450 m above sea level the ice, flows into the Isel in the form of "glacier milk" and gives it its at the Umbalkees (Glacier) characteristic turbidity. This uniqueness is also reflected in its diversity: Length: 58 km the Isel and its tributaries are a treasure trove of nature and provide Feeding area: 1 200 km2 (=2/3 of the habitats for numerous endangered animal and plant species. area of East Tyrol) Estuary: into the Drau near Lienz The fact that the Isel is still in such a good condition today is due Water flow at mouth: 40 m3/s to the foresight of committed conservationists who have been (= three times more than Drau itself leads and ¾ of all the East Tyrolean vehemently and successfully fighting against the obstruction of water) the glacial river for decades. -

3 Study Area and Tisenjoch (Latitude 46°50’N, Longitude 10°50’E)

3 Study area and Tisenjoch (latitude 46°50’N, longitude 10°50’E). For a general view of the studied area and the investigated 1 km² squares see The study area centres on the site of the Fig. 1-3 (attachement). The core area with the Iceman and extends north and south of valleys and mountain ridges (Fig. 1) around the the watershed, i.e., the main divide of the Iceman site is colloquially known as “Ötziland” Alps (Fig. 1-3, see attachment). The region (Dickson 2011b). where the Iceman was found is still referred The core area comprises Vinschgau (Naturns to as Tyrol (Tirol). In 1919, the southern village, Castle Juval, Schlanders village), the part (South Tyrol, Südtirol) became part of Schnalstal (the villages of St. Katharinaberg, Italy and the northern part (North Tyrol, Karthaus, Vernagt and Unser Frau) up to Nordtirol) remained Austrian. In the past, Kurzras village with the side valleys Pfossental, the area with the main municipalities Schnals Klosteralm, Penaudtal, Mastauntal, Finailtal and Vent belonged to the county of Tschars and Tisental leading up to the discovery place (Vinschgau, South Tyrol), but after World of the Iceman. Also the Schlandrauntal/ War I, Vent was merged with the municip- Taschljöchl and the Pfelderertal until it leads ality of Sölden, whereas the whole southern into the Passeiertal were investigated. On the area became Italian. The area played an es- Austrian side, leading down from the Iceman sential role in the development of alpinism, site beside the Niederjochferner (glacier), the alpine tourism and the foundation of the study sites comprise Niedertal with Vent, continental Alpine Club which was initialised Zwieselstein and Nachtberg/Sölden as well by the famous clergyman Franz Senn (Vent) as the Rofental and Tiefenbachtal/Tiefenbach and his companions. -

FLEXIBLE TRANSPORT SYSTEMS TECHNICAL STATE of the ART East Tyrol, Austria

LAST MILE – Let´s travel the last mile together! FLEXIBLE TRANSPORT SYSTEMS TECHNICAL STATE OF THE ART East Tyrol, Austria Regional state-of-the-art analysis Region EAST TYROL The region East Tyrol counts 33 municipalities and is a district in the eastern part of the federal state Tyrol/Austria. The region is Area (km2) 2.020 km2 characterized by alpine and rural landscape. Due to low population densities and scattered settlements the insufficient quality of public Inhabitants 49.026 transport can not cover all transportation needs. The modal split in East Tyrol is predominantly by private car. A range of touristic hot spots suffer from insufficient sustainable mobility offer. In this context, the respective transport offer (public transport, transport infrastructure, • 296 km state road etc.) as well as the long-term financial viability is still a challenge for the Regional • 1.074 km local road network municipalities and private taxi operators. Improvements in transport are transport • 2.819 km other local roadways required, in addition to the necessary expansion of infrastructure in the network • ÖBB rail lines to Villach, Salzburg and Vienna and South area of transport by modifying mobility behaviour and economic. Tyrol (Italy). • daily regional (express) trains and express busses ensure public transport connection from Lienz to the state Sustainable capital Innsbruck transport network • public bus services provided from regional transport association Verkehrsverbund Tirol (VVT) to all valleys (20 lines) • DefMobil: hailed shared taxi-bus, which fills gaps of existing public transport services and provides residents and tourists an improved range of mobility. • Virger Mobil and Assling Mobil: offer citizens a Flexible complementary municipality owned transport service, transport designed as hailed shared taxis. -

Bavaria & the Tyrol

AUSTRIA & GERMANY Bavaria & the Tyrol A Guided Walking Adventure Table of Contents Daily Itinerary ........................................................................... 4 Tour Itinerary Overview .......................................................... 13 Tour Facts at a Glance ........................................................... 15 Traveling To and From Your Tour .......................................... 17 Information & Policies ............................................................ 20 Austria at a Glance ................................................................. 22 Germany at a Glance ............................................................. 26 Packing List ........................................................................... 31 800.464.9255 / countrywalkers.com 2 © 2015 Otago, LLC dba Country Walkers Travel Style This small-group Guided Walking Adventure offers an authentic travel experience, one that takes you away from the crowds and deep in to the fabric of local life. On it, you’ll enjoy 24/7 expert guides, premium accommodations, delicious meals, effortless transportation, and local wine or beer with dinner. Rest assured that every trip detail has been anticipated so you’re free to enjoy an adventure that exceeds your expectations. And, with our optional Flight + Tour ComboCombo,, Munich PrePre----TourTour Extension and Salzbug PostPost----TourTour Extension to complement this destination, we take care of all the travel to simplify the journey. Refer to the attached itinerary for more details. -

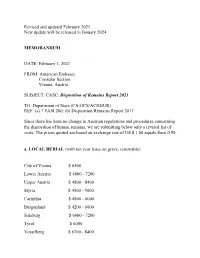

Disposition of Remains Report 2021

Revised and updated February 2021 New update will be released in January 2024 MEMORANDUM DATE: February 1, 2021 FROM: American Embassy Consular Section Vienna, Austria SUBJECT: CASC: Disposition of Remains Report 2021 TO: Department of State (CA/OCS/ACS/EUR) REF: (a) 7 FAM 260; (b) Disposition Remains Report 2017 Since there has been no change in Austrian regulations and procedures concerning the disposition of human remains, we are submitting below only a revised list of costs. The prices quoted are based on exchange rate of US $ 1.00 equals Euro 0.90. a. LOCAL BURIAL (with ten year lease on grave, renewable) City of Vienna $ 6500 Lower Austria $ 4800 - 7200 Upper Austria $ 4800 - 8400 Styria $ 4200 - 5000 Carinthia $ 4800 - 6000 Burgenland $ 4200 - 6000 Salzburg $ 6000 - 7200 Tyrol $ 6000 Vorarlberg $ 6700 - 8400 b. PREPARATION OF REMAINS FOR SHIPMENT TO THE UNITED STATES Vienna $ 6000 Lower Austria $ 6000 - 8900 Upper Austria $ 6000 - 8400 Styria $ 6000 - 8400 Carinthia $ 4800 - 6000 Burgenland $ 4800 - 7200 Salzburg $ 6000 Tyrol $ 6000 Vorarlberg $ 8900 c. COST OF SHIPPING PREPARED REMAINS TO THE UNITED STATES East Coast $ 2900 South Coast $ 2900 Central $ 2900 West Coast $ 3200 Shipping costs are based on an average weight of the casket with remains to be 150 kilos. d. CREMATION AND LOCAL BURIAL OF URN Vienna $ 5800 Lower Austria $ 9000 Upper Austria $ 3400 - 6700 Styria $ 4200 - 5000 Carinthia $ 5000 Burgenland $ 4200 - 5900 Salzburg (city) $ 4200 - 5900 Salzburg (province) $ 5500 Tyrol $ 5900 Vorarlberg $ 8400 e. CREMATION AND SHIPMENT OF URN TO THE UNITED STATES Vienna $ 3600 Lower Austria $ 4800 Upper Austria $ 3600 Styria $ 3600 Carinthia $ 4800 Burgenland $ 4800 Salzburg $ 3600 Tyrol $ 4200 Vorarlberg $ 6000 e. -

Fascist Legacies: the Controversy Over Mussolini’S Monuments in South Tyrol

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, Department of History History, Department of 2013 Fascist Legacies: The Controversy over Mussolini’s Monuments in South Tyrol Gerald Steinacher University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historyfacpub Steinacher, Gerald, "Fascist Legacies: The Controversy over Mussolini’s Monuments in South Tyrol" (2013). Faculty Publications, Department of History. 144. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historyfacpub/144 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Gerald Steinacher* Fascist Legacies:1 Th e Controversy over Mussolini’s Monuments in South Tyrol2 Th e northern Italian town of Bolzano (Bozen in German) in the western Dolomites is known for breathtaking natural landscapes as well as for its medieval city centre, gothic cathedral, and world-famous mummy, Ötzi the Iceman, which is on dis- play at the local archaeological museum. At the same time, Bolzano’s more recent history casts a shadow over the town. Th e legacy of fascism looms large in the form of Ventennio fascista-era monuments such as the Victory Monument, a mas- sive triumphal arch commissioned by the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini and located in Bolzano’s Victory Square, and the Mussolini relief on the façade of the former Fascist Party headquarters (now a tax offi ce) at Courthouse Square, which depicts il duce riding a horse with his arm raised high in the Fascist salute. -

Austrian Neutrality in Postwar Europe

67 - 12,294 SCHLESINGER, Thomas Otto, 1925- AUSTRIAN NEUTRALITY IN POSTWAR EUROPE. The American University, Ph.D„ 1967 Political Science, international law and relations University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan © Copyright by Thomas Otto Schlesinger 1967 AUSTRIAN NEUTRALITY IN POSTWAR EUROPE BY THOMAS OTTO SCHLESINGER Submitted to the Faculty of the School of International Service of The American University In Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS Signatures of Committee: RttAU Chairma Acting Dean: yilember Member auu. 2 rt£ 7 Datete Approved 2 , 7 June 1967 The American University AMERICAN UNIVERSITY LIRPAOY Washington, D. C. MAY 2 a mi A crMn PREFACE In thought, this dissertation began during the candi date's military service as interpreter to the United States military commanders in Austria, 1954-1955, and northern Italy, 1955-1957. Such assignments, during an army career concluded by retirement in 1964, were in part brought about by the author's European background— birth in Berlin, Ger many, and some secondary schooling in Italy and Switzerland. These circumstances should justify the author's own trans lation— and responsibility therefor— of the German, French, and Italian sources so widely used, and of the quotations taken from these. As will become obvious to any reader who continues for even a few pages, the theoretical conception for this study derives in large part from the teachings of the late Charles O. Lerche, Jr., who was Dean of the School of Inter national Service when the dissertation was proposed. While Dean Lerche's name could not appear in the customary place for approval, the lasting inspiration he provided makes it proper that this student's deepest respect and admiration for him be recorded here. -

Trentino, South Tyrol & the Dolomites

NO SINGLE SUPPLEMENT for Solo Travelers LAND SMALL GROUP JO URNEY Ma xi mum of 24 Travele rs Trentino, South Tyrol & the Dolomites Undiscovered Italy Inspiring Moments > Be captivated by the extraordinary beauty of the Dolomites, a canvas of snow- dusted peaks, spectacular rock formations and cascading emerald vineyards. > Discover an idyllic clutch of pretty piazzas, INCLUDED FEATURES serene parks and an ancient Roman arena in the setting for Accommodations (with baggage handling) Itinerary romantic Verona, – 7 nights in Trento, Italy, at the first-class Day 1 Depart gateway city Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet.” Grand Hotel Trento. Day 2 Arrive in Verona and transfer > Cruise Lake Garda, ringed by vineyards, to hotel in Trento lemon gardens and attractive harbors. Extensive Meal Program > From polenta to strudel to savory bread – 7 breakfasts, 3 lunches and 3 dinners, Day 3 Trento including Welcome and Farewell Dinners; Day 4 Lake Molveno | Madonna di dumplings known as canederli, dine on tea or coffee with all meals, plus wine Campiglio | Adamello-Brenta traditional dishes of northeastern Italy. with dinner. Nature Park > Relax over a delicious lunch at a chalet Day 5 Verona surrounded by breathtaking vistas. Your One-of-a-Kind Journey > Explore the old-world charm of Bolzano, – Discovery excursions highlight the local Day 6 Ortisei | Bolzano culture, heritage and history. Day 7 Limone sul Garda | Lake Garda | with its enticing blend of German and Italian cultures. – Expert-led Enrichment programs Malcensine enhance your insight into the region. Day 8 Trento > Experience two UNESCO World Heritage sites. – AHI Sustainability Promise: Day 9 Transfer to Verona airport We strive to make a positive, purposeful and depart for gateway city impact in the communities we visit. -

The Bronze and Iron Alpine Ash Altar Material in the Frankfurth Collection at the Milwaukee Public Museum William Arnold University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2014 Fire on the Mountain: the Bronze and Iron Alpine Ash Altar Material in the Frankfurth Collection at the Milwaukee Public Museum William Arnold University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, and the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Arnold, William, "Fire on the Mountain: the Bronze and Iron Alpine Ash Altar Material in the Frankfurth Collection at the Milwaukee Public Museum" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 352. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/352 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FIRE ON THE MOUNTAIN: THE BRONZE AND IRON ALPINE ASH ALTAR MATERIAL IN THE FRANKFURTH COLLECTION AT THE MILWAUKEE PUBLIC MUSEUM by W. Brett Arnold A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Anthropology at The University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee May 2014 ABSTRACT FIRE ON THE MOUNTAIN: THE BRONZE AND IRONALPINE ASH ALTAR MATERIAL IN THE FRANKFURTH COLLECTION AT THE MILWAUKEE PUBLIC MUSEUM by W. Brett Arnold The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2014 Under the Supervision of Professor Bettina Arnold Milwaukee Public Museum (MPM) Accession 213 is one of many collections orphaned by nineteenth century antiquarian collecting practices. Much of the European prehistoric and early historic material in MPM Accession 213 was collected in a single two-year period from December 1889 to December 1891, but the sudden death of the donor—William Frankfurth—and the passage of a decade between collection and donation left the museum without much context for the materials.