SOUTH TYROL in COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE1 Stefan Wolff I. Introduction the Instituti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bavaria & the Tyrol

AUSTRIA & GERMANY Bavaria & the Tyrol A Guided Walking Adventure Table of Contents Daily Itinerary ........................................................................... 4 Tour Itinerary Overview .......................................................... 13 Tour Facts at a Glance ........................................................... 15 Traveling To and From Your Tour .......................................... 17 Information & Policies ............................................................ 20 Austria at a Glance ................................................................. 22 Germany at a Glance ............................................................. 26 Packing List ........................................................................... 31 800.464.9255 / countrywalkers.com 2 © 2015 Otago, LLC dba Country Walkers Travel Style This small-group Guided Walking Adventure offers an authentic travel experience, one that takes you away from the crowds and deep in to the fabric of local life. On it, you’ll enjoy 24/7 expert guides, premium accommodations, delicious meals, effortless transportation, and local wine or beer with dinner. Rest assured that every trip detail has been anticipated so you’re free to enjoy an adventure that exceeds your expectations. And, with our optional Flight + Tour ComboCombo,, Munich PrePre----TourTour Extension and Salzbug PostPost----TourTour Extension to complement this destination, we take care of all the travel to simplify the journey. Refer to the attached itinerary for more details. -

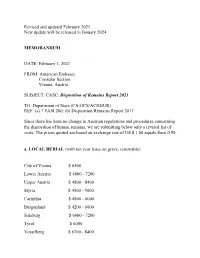

Disposition of Remains Report 2021

Revised and updated February 2021 New update will be released in January 2024 MEMORANDUM DATE: February 1, 2021 FROM: American Embassy Consular Section Vienna, Austria SUBJECT: CASC: Disposition of Remains Report 2021 TO: Department of State (CA/OCS/ACS/EUR) REF: (a) 7 FAM 260; (b) Disposition Remains Report 2017 Since there has been no change in Austrian regulations and procedures concerning the disposition of human remains, we are submitting below only a revised list of costs. The prices quoted are based on exchange rate of US $ 1.00 equals Euro 0.90. a. LOCAL BURIAL (with ten year lease on grave, renewable) City of Vienna $ 6500 Lower Austria $ 4800 - 7200 Upper Austria $ 4800 - 8400 Styria $ 4200 - 5000 Carinthia $ 4800 - 6000 Burgenland $ 4200 - 6000 Salzburg $ 6000 - 7200 Tyrol $ 6000 Vorarlberg $ 6700 - 8400 b. PREPARATION OF REMAINS FOR SHIPMENT TO THE UNITED STATES Vienna $ 6000 Lower Austria $ 6000 - 8900 Upper Austria $ 6000 - 8400 Styria $ 6000 - 8400 Carinthia $ 4800 - 6000 Burgenland $ 4800 - 7200 Salzburg $ 6000 Tyrol $ 6000 Vorarlberg $ 8900 c. COST OF SHIPPING PREPARED REMAINS TO THE UNITED STATES East Coast $ 2900 South Coast $ 2900 Central $ 2900 West Coast $ 3200 Shipping costs are based on an average weight of the casket with remains to be 150 kilos. d. CREMATION AND LOCAL BURIAL OF URN Vienna $ 5800 Lower Austria $ 9000 Upper Austria $ 3400 - 6700 Styria $ 4200 - 5000 Carinthia $ 5000 Burgenland $ 4200 - 5900 Salzburg (city) $ 4200 - 5900 Salzburg (province) $ 5500 Tyrol $ 5900 Vorarlberg $ 8400 e. CREMATION AND SHIPMENT OF URN TO THE UNITED STATES Vienna $ 3600 Lower Austria $ 4800 Upper Austria $ 3600 Styria $ 3600 Carinthia $ 4800 Burgenland $ 4800 Salzburg $ 3600 Tyrol $ 4200 Vorarlberg $ 6000 e. -

Fascist Legacies: the Controversy Over Mussolini’S Monuments in South Tyrol

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, Department of History History, Department of 2013 Fascist Legacies: The Controversy over Mussolini’s Monuments in South Tyrol Gerald Steinacher University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historyfacpub Steinacher, Gerald, "Fascist Legacies: The Controversy over Mussolini’s Monuments in South Tyrol" (2013). Faculty Publications, Department of History. 144. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historyfacpub/144 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Gerald Steinacher* Fascist Legacies:1 Th e Controversy over Mussolini’s Monuments in South Tyrol2 Th e northern Italian town of Bolzano (Bozen in German) in the western Dolomites is known for breathtaking natural landscapes as well as for its medieval city centre, gothic cathedral, and world-famous mummy, Ötzi the Iceman, which is on dis- play at the local archaeological museum. At the same time, Bolzano’s more recent history casts a shadow over the town. Th e legacy of fascism looms large in the form of Ventennio fascista-era monuments such as the Victory Monument, a mas- sive triumphal arch commissioned by the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini and located in Bolzano’s Victory Square, and the Mussolini relief on the façade of the former Fascist Party headquarters (now a tax offi ce) at Courthouse Square, which depicts il duce riding a horse with his arm raised high in the Fascist salute. -

The South Tyrol Question, 1866–2010 10 CIS ISBN 978-3-03911-336-1 CIS S E I T U D S T Y I D E N T I Was Born in the Lower Rhine Valley in Northwest Germany

C ULTURAL IDENT I TY STUD I E S The South Tyrol Question, CIS 1866–2010 Georg Grote From National Rage to Regional State South Tyrol is a small, mountainous area located in the central Alps. Despite its modest geographical size, it has come to represent a success story in the Georg Grote protection of ethnic minorities in Europe. When Austrian South Tyrol was given to Italy in 1919, about 200,000 German and Ladin speakers became Italian citizens overnight. Despite Italy’s attempts to Italianize the South Tyroleans, especially during the Fascist era from 1922 to 1943, they sought to Question, 1866–2010 Tyrol South The maintain their traditions and language, culminating in violence in the 1960s. In 1972 South Tyrol finally gained geographical and cultural autonomy from Italy, leading to the ‘regional state’ of 2010. This book, drawing on the latest research in Italian and German, provides a fresh analysis of this dynamic and turbulent period of South Tyrolean and European history. The author provides new insights into the political and cultural evolution of the understanding of the region and the definition of its role within the European framework. In a broader sense, the study also analyses the shift in paradigms from historical nationalism to modern regionalism against the backdrop of European, global, national and local historical developments as well as the shaping of the distinct identities of its multilingual and multi-ethnic population. Georg Grote was born in the Lower Rhine Valley in northwest Germany. He has lived in Ireland since 1993 and lectures in Western European history at CIS University College Dublin. -

Austria – South Tyrol/Alto Adige

Call for International Cooperation Projects (“Joint Projects”) Austria – South Tyrol/Alto Adige Table of contents 1. General information ..................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Duration of the project ........................................................................................... 2 1.2. Thematic focus ...................................................................................................... 2 1.3. Deadline ................................................................................................................ 2 2. Submission of applications ......................................................................................... 2 2.1. Form requirements of the FWF .............................................................................. 2 2.2. Form requirements of the Autonomous Province of Bolzano/Bozen – South Tyrol 3 3. Processing time ............................................................................................................ 3 4. Project administration .................................................................................................. 3 5. Contact .......................................................................................................................... 4 1. General information The Autonomous Province of Bolzano/Bozen – South Tyrol and the FWF jointly request applications for bilateral, cross-border research projects. A bilateral project must be designed in such a way that each partner’s -

Sub-National Constitutionalism in Austria: a Historical Institutionalist Perspective by Ferdinand Karlhofer

ISSN: 2036-5438 Sub-national Constitutionalism in Austria: a Historical Institutionalist Perspective by Ferdinand Karlhofer Perspectives on Federalism, Vol. 7, issue 1, 2015 Except where otherwise noted content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons 2.5 Italy License E - 57 Abstract Austria’s federal system is determined by an apparent contrast between formal and real constitution having its roots in foundational defects shaping the system to the present day. As for the formal dimension, Austria has a rather uneven balance with regard to power- sharing. No wonder that, given the structural bias between central state and substates, informal forces are at work in order to make up for the shortcomings of the federal architecture. In this context, sub-national constitutionalism at first sight appears to be marginal. Astoundingly, though, in recent time a lot of constitutional changes and amendments, quite possibly paving the way for a sustainable redesign of the federation as a whole have taken place. The article starts with a historical outline of the Austrian federation’s origins. In chapter 2, the interplay of formal and informal rules and practices is discussed. Chapter 3 deals with scope, contents and dynamics of sub-national constitutionalism under the given framework. The article concludes with assessing the efficacy of subconstitutional politics in relation to the capacities of the federal constitution. Key-words Federalism, Subnational constitutionalism, Austria, Historical institutionalism Except where otherwise noted content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons 2.5 Italy License E - 58 Given that federalism is essentially about the distribution of authority between a central government and state governments (Bednar 2011: 270), every two-tiered political system is defined through a “super-constitution” that regulates overlapping control of a single population by a superior state and a group of subordinate states. -

The South Tyrol and the Principle of Self-Determination

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1994 The outhS Tyrol and the Principle of Self- Determination: An Analysis of a Minority Problem Eva Pfanzelter This research is a product of the graduate program in History at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Pfanzelter, Eva, "The outhS Tyrol and the Principle of Self-Determination: An Analysis of a Minority Problem" (1994). Masters Theses. 2050. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2050 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THESIS REPRODUCTION CERTIFICATE TO: Graduate Degree Candidates (who have written formal theses) SUBJECT: Permission to Reproduce Theses The University Library is rece1v1ng a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. PLEASE SIGN ONE OF THE FOLLOWING STATEMENTS: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclus~on in that institution's library or research holdings. 3--6\-9Y Date I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis to be reproduced because: Author Date The South Tyrol and the Principle of Self-Determination. -

Superdiversity and Sub-National Autonomous

Policy & Politics • vol 45 • no 4 • 547–66 • © Policy Press 2017 • #PPjnl @policy_politics Print ISSN 0305 5736 • Online ISSN 1470 8442 • http://dx.doi.org/10.1332/030557316X14817331774662 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits adaptation, alteration, reproduction and distribution for non-commercial use, without further permission provided the original work is attributed. The derivative works do not need to be licensed on the same terms. Accepted for publication 11 May 2017 • First published online 20 June 2017 SPECIAL ISSUE • Superdiversity, Policy and Governance in Europe: Multi-scalar Perspectives article Superdiversity and sub-national autonomous regions: perspectives from the South Tyrolean case Roberta Medda-Windischer, [email protected] European Academy of Bolzano/Bozen (EURAC), Italy For many sub-national autonomous territories where traditional-historical groups (‘old minorities’) migration is a stable and increasingly important reality. From the perspective of the autonomous province of Bozen/Bolzano in Italy (South Tyrol), I will analyse whether the interests and claims of old and new minority groups are in permanent conflict and tension, or whether they can develop through various forms of synergy and collaboration. The aim of this contribution is to provide deeper insights into the governance of superdiversity by looking at the perspective of sub-national units characterised by the presence -

Karst Geology and Cave Fauna of Austria: a Concise Review

International Journal of Speleology 39 (2) 71-90 Bologna (Italy) July 2010 Available online at www.ijs.speleo.it International Journal of Speleology Official Journal of Union Internationale de Spéléologie Karst geology and cave fauna of Austria: a concise review Erhard Christian1 and Christoph Spötl2 Abstract: Christian E. & Spötl C. 2010. Karst geology and cave fauna of Austria: a concise review. International Journal of Speleology, 39 (2), 71-90. Bologna (Italy). ISSN 0392-6672. The state of cave research in Austria is outlined from the geological and zoological perspective. Geologic sections include the setting of karst regions, tectonic and palaeoclimatic control on karst, modern cave environments, and karst hydrology. A chapter on the development of Austrian biospeleology in the 20th century is followed by a survey of terrestrial underground habitats, biogeographic remarks, and an annotated selection of subterranean invertebrates. Keywords: karst, caves, geospeleology, biospeleology, Austria Received 8 January 2010; Revised 8 April 2010; Accepted 10 May 2010 INTRODUCTION be it temporarily in a certain phase of the animal’s Austria has a long tradition of karst-related research life cycle (subtroglophiles), permanently in certain going back to the 19th century, when the present- populations (eutroglophiles), or permanently across day country was part of the much larger Austro- the entire species (troglobionts). An easy task as Hungarian Empire. Franz Kraus was among the first long as terrestrial metazoans are considered, this worldwide to summarise the existing knowledge in undertaking proves intricate with aquatic organisms. a textbook, Höhlenkunde (Kraus, 1894; reprinted We do not know of any Austrian air-breathing species 2009). -

Suburban Processes of Islandisation in Austria: the Cases of Vienna and Tyrol

Suburban Processes of Islandisation in Austria: The Cases of Vienna and Tyrol Wolfgang Andexlinger Faculty of Architecture, University of Innsbruck [email protected] Abstract: Suburban areas are often described as monotonous and generic. In Europe, however, suburban areas show distinct morphological and functional configurations in different regions due to cultural, spatial, economic, and institutional conditions. This paper compares recent suburban developments in Austria in the region south of Vienna and in the region of Tyrol, highlighting significant developments after 1985 in the fields of housing, shopping, leisure, and commercial sites. Using quantitative (aerial images, statistical data, plans) and qualitative (case studies) methods, the paper analyses the distinct morphological similarities of selected case studies and tries to answer two questions. First, how can these developments be assessed from the viewpoint of urban and spatial planning? Second, what spatial strategies could be useful for further interventions? It is concluded that these developments can be understood as island-like developments. This means that hybrid suburban structures have appeared where sharp-edged boundaries separate single elements from adjacent ones. These island-like developments have increased dramatically over the past decades and are today to a large extent characteristic of Austrian suburbs. Capitalism, market liberalisation, and prevailing planning regulations and culture are driving these processes of islandisation. The paper furthermore shows that new spatial strategies are required for creating more coherent spaces. Interstitial landscape as a planning tool seems to be one option for creating more livable and sustainable suburban areas in the future. Keywords: Suburbs, island cities, islandisation, island-like developments, urban planning, Vienna, Tyrol © 2015 Wolfgang Andexlinger Island Dynamics, Denmark - http://www.urbanislandstudies.org This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. -

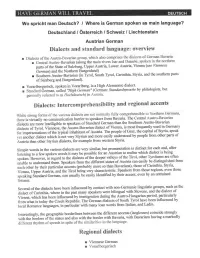

Dialects and Standard Language

HA VE GERMAN WILL TRAVEL DEUTSCH Wo spricht man Deutsch? I Where is German spoken as main language? Deutschland I Osterreich / Schweiz I Liechtenstein Austrian German Dialects and standard language: overview ■ Dialects of the Austro-Bavarian group, which also comprises the dialects of German Bavaria ■ Central Austro-Bavarian (along the main rivers Isar and Danube, spoken in the northern parts of the State of Salzburg, Upper Austria, Lower Austria, Vienna (see Viennese German) and the Northern Burgenland) ■ Southern Austro-Bavarian (in Tyrol, South Tyrol, Carinthia, Styria, and the southern parts of Salzburg and Burgenland). ■ Vorarlbergerisch, spoken in Vorarlberg, is a High A1emannic dialect. ■ Standard German, called "High German" (German: Standardsprache by philologists, but generally referred to as Hochdeutsch) in Austria. Dialects: lntercomprehensibility and regional accents While strong forms of the various dialects are not normally fully comprehensible to Northern Germans, there is virtually no communication barrier to speakers from Bavaria. The Central Austro-Bavarian dialects are more intelligible to speakers of Standard German than the Southern Austro-Bavarian dialects of Tyrol. Viennese, the Austro-Bavarian dialect of Vienna, is most frequently used in Germany for impersonations of the typical inhabitant of Austria. The people of Graz, the capital of Styria, speak yet another dialect which is not very Styrian and more easily understood by people from other parts of Austria than other Styrian dialects, for example from western Styria. Simple words in the various dialects are very similar, but pronunciation is distinct for each and, after listening to a few spoken words it may be possible for an Austrian to realise which dialect is being spoken. -

South Tyrol Again

INSTITUTE OF CURRENT 7ORLD AFFAIRS DR 5 St. Antony's College South Tyrel Again: Oxford, England. BAS, Bembs, and the One-Party State 25 January 1961 Mr. Richard H. Nolte, Inst+/-tute of Current World Affairs, 66 Madison Avenue, New York 17, N.Y. Dear Mr. Nolte, In Bolzano-Bozen the dust is still settling after the United Nations debate on the South Tyrol question. Tyrolean radicals who were in New York, like Friedl Volgger of the Dolomlten, are hailing the debate itself and the resolution th' came out of it as "undoubtedly" an Austrian victory, and Italian Neo-Fascist deputies in Rome have angrily agreed with this analysis. Tyrolean moderates also in New York, like Senator Luis Sand, protest that any attempt to name a victor in such a debate is "senseless", but they seem moderately pleased- or slightly relieved. All reported "disillusionment" with the American attitude, viewed as placing the interests of a NATO ally (Italy) ahead of the demands of justice. Italians are generally annoyed that the debate took place at all, and resulted in the acceptance of a compromise resolution, but they are generally satisfied that the Tyroleans received so little support from the uncommitted nations, and none from the Soviet block. Such were my impressions after a Christmas visit to the disputed area. The date of the visit is important, because it meant that most of the people ne wanted to talk to were out of town and unavailable. (I even pursued one of them by cable- lift and horse-drawn sleigh deep into the Dolomites, but failed to catch him.