Second Language Learning Issues in South Tyrol Ann Wand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Abstract Book

1 SnowHydro 2020 International Conference on Snow Hydrology Challenges in Mountain Areas 28th – 31st January 2020, Bolzano/Bozen, Italy Responsible organizers Claudia Notarnicola – EURAC Research (Italy) – Scientific coordinator Giacomo Bertoldi – EURAC Research (Italy) – Scientific advisor María José Polo – University of Cordóba (Spain) – Scientific advisor Lucas Menzel – University of Heidelberg (Germany) – Scientific advisor Paola Winkler - EURAC Research (Italy) – Project manager Venue EURAC, lecture room “Auditorium”. 2 Welcome to the SnowHydro Conference in Bolzano/Bozen 2020 Snow is a dynamically changing water resource that plays an important role in the hydrological cycle in mountainous areas. Snow cover contributes to regulate the Earth surface temperature, and once it melts, the water helps fill rivers and reservoirs in many regions of the world. In terms of spatial extent, seasonal snow cover is the largest single component of the cryosphere and has a mean winter maximum areal extent of 47 million square kilometers, about 98% of which is located in the Northern Hemisphere. While on large scale snow cover changes affect the energy exchange between Earth’s surface and the atmosphere and are, thus, useful indicators of climatic variation, on a smaller scale, variations in snow cover can affect regional weather patterns. Therefore, snow cover is an important climate change variable because of its influence on energy and moisture budgets. The strong consequences of changes in snow amount on Earth's environment and population, have led scientists to develop ways for continuously measuring and monitoring snow and its properties. The traditional snow observations consist of in situ measurements during periodic field campaigns at fixed sites or through automatic nivological stations network recording snow parameters and often are coupled to weather stations. -

Distretti Sanitari in Alto Adige

Distretti sanitari in Alto Adige. Nella colonna a sinistra Lei trova il suo comune. Nella colonna centrale Lei trova: Qual è il mio distretto sanitario? E nella colonna a destra Lei trova: Di quale comprensorio sanitario fa parte il mio distretto sanitario? Comune Distretto sanitario Comprensorio sanitario Aldino Bassa Atesina Bolzano 0471 82 92 06 [email protected] Andriano Oltradige Bolzano 0471 67 08 80 [email protected] Anterivo Bassa Atesina Bolzano 0471 82 92 06 [email protected] Appiano Oltradige Bolzano 0471 67 08 80 [email protected] Avelengo Merano circondario Merano 0473 49 67 06 [email protected] 1 Badia Val Badia Brunico 0474 58 61 20 [email protected] Barbiano Chiusa circondario Bressanone 0472 81 31 30 [email protected] Bolzano: Centro - Piani - Rencio Bolzano Centro - Piani - 0471 31 95 03 Rencio [email protected] Bolzano: Oltrisarco Bolzano Oltrisarco 0471 46 94 25 [email protected] Bolzano: Gries - San Quirino Bolzano Gries - San Quirino 0471 90 91 22 oppure 0471 90 91 13 [email protected] Bolzano: Europa - Novacella Bolzano Europa - Novacella 0471 54 11 01 oppure 0471 54 11 02 [email protected] Bolzano: Don Bosco Bolzano Don Bosco 0471 54 10 10 [email protected] Braies Alta Val Pusteria Brunico 0474 91 74 50 [email protected] 2 Brennero Alta Valle Isarco Bressanone 0472 77 46 22 [email protected] Bressanone Bressanone circondario Bressanone 0472 81 36 40 [email protected] -

The North-South Divide in Italy: Reality Or Perception?

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk EUROPEAN SPATIAL RESEARCH AND POLICY Volume 25 2018 Number 1 http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/1231-1952.25.1.03 Dario MUSOLINO∗ THE NORTH-SOUTH DIVIDE IN ITALY: REALITY OR PERCEPTION? Abstract. Although the literature about the objective socio-economic characteristics of the Italian North- South divide is wide and exhaustive, the question of how it is perceived is much less investigated and studied. Moreover, the consistency between the reality and the perception of the North-South divide is completely unexplored. The paper presents and discusses some relevant analyses on this issue, using the findings of a research study on the stated locational preferences of entrepreneurs in Italy. Its ultimate aim, therefore, is to suggest a new approach to the analysis of the macro-regional development gaps. What emerges from these analyses is that the perception of the North-South divide is not consistent with its objective economic characteristics. One of these inconsistencies concerns the width of the ‘per- ception gap’, which is bigger than the ‘reality gap’. Another inconsistency concerns how entrepreneurs perceive in their mental maps regions and provinces in Northern and Southern Italy. The impression is that Italian entrepreneurs have a stereotyped, much too negative, image of Southern Italy, almost a ‘wall in the head’, as also can be observed in the German case (with respect to the East-West divide). Keywords: North-South divide, stated locational preferences, perception, image. 1. INTRODUCTION The North-South divide1 is probably the most known and most persistent charac- teristic of the Italian economic geography. -

Merancard? the Merancard Is an Advantage Card, Which Is Handed out to Guests in Partici- Pating Partner Accomodations in Merano and Environs

» What is the MeranCard? The MeranCard is an advantage card, which is handed out to guests in partici- pating partner accomodations in Merano and environs. The card is included in the room price and grants access to a number of services without additional charge or at a discounted price (see included services). » How long is the MeranCard valid? The MeranCard is valid from 15th October 2018 to 30th June 2019. The card is valid for your entire stay, provided that it coincides with the validity period of the card. Should you stay for longer than one week, you are entitled to another card. The MeranCard must be validated each time when using public transportation or visiting a museum. In order to benefit from the discounts, the card must MeranCard MERANCARD - INCLUDED SERVICES presented in advance. 2018 /2019 » Who receives the MeranCard? Your advantage card » Bus and train All guests staying at a partner accomodation in Merano and environs get a in Merano and Environs – Use of all public means of transportation belonging card of their own. Children aged between 6 and 14 get a junior card. 15th october 2018 - 30th june 2019 to the South Tyrol Integrated Transport Network: Children under the age of 6, accompanied by an adult holding the MeranCard, all city and extra – urban buses do not require a card of their own. – Regional trains in South Tyrol (Brennero – Trento, Malles – The card is personalized and cannot be transferred. The MeranCard is not San Candido). The card is not valid on Italian InterRegional available for purchase and is handed out to guests with at least one overnight trains or on OEBB, DB, Eurostar or Intercity trains. -

Studia Territorialia 2 2017 6150.Indd

2017 ACTA UNIVERSITATIS CAROLINAE PAG. 11–34 STUDIA TERRITORIALIA 2 TRANSFORMING A CONTROVERSIAL HERITAGE: THE CASE OF THE FASCIST VICTORY MONUMENT IN SOUTH TYROL ANDREA CARLÀ EURAC RESEARCH – INSTITUTE FOR MINORITY RIGHTS JOHANNA MITTERHOFER EURAC RESEARCH – INSTITUTE FOR MINORITY RIGHTS Abstract Using a Fascist monument in South Tyrol, Northern Italy as a case study, this paper investigates the role of monuments in managing and negotiating interpretations of the past in culturally het- erogeneous societies. It explores approaches to overcoming the exclusionary potential of cultural heritage, reframing it in more inclusive, pluralist terms. It provides an in-depth analysis of a dialog- ical, pluralistic approach to heritage, which allows divergent, even contrary, interpretations of the past to coexist. Thus, the paper sheds light on how monuments (re)construct and contest memory and history. It provides insights into constructive ways of engaging with a controversial heritage in multiethnic societies. Keywords: cultural heritage; fascism; memory; monuments; reconciliation; South Tyrol; multi- ethnic societies DOI: 10.14712/23363231.2018.1 Introduction The Victory Monument in Bolzano/Bozen, a town in the province of South Tyrol in northern Italy, immediately reminds the visitor of the fascist period in which it was erected. Its columns resemble the lictoral fasces, which later became a model for a key element of fascist architecture. An inscription in Latin reads, Dr. Andrea Carlà and Johanna Mitterhofer are researchers at the Institute for Minority Rights of Eurac Research in Bolzano/Bozen. Address correspondence to Dr. Andrea Carlà, Institute for Mi- nority Rights, Eurac Research, Viale Druso 1, 39100 Bolzano/Bozen, Italy. E-mail: [email protected]. -

ASSESSMENT REGIONAL REPORT Deliverable 3.7.2 EURAC RESEARCH

WP-T2 ASSESSMENT REGIONAL REPORT Deliverable 3.7.2 EURAC RESEARCH Val Passiria – Province of Bolzano/South Tyrol August 2017 • Eurac Research WP-T2 Regional Report: Val Passiria Institution Eurac Research Institute for Regional Development Viale Druso, 1 / Drususallee 1 39100 Bolzano / Bozen – Italy t +39 0471 055 300 f +39 0471 055 429 e [email protected] w www.eurac.edu Authors Clare Giuliani Junior Researcher and Project Assistant Viale Druso 1, I-39100 Bolzano t +39 0471 055 435 f +39 0471 055 429 [email protected] Christian Hoffmann Senior Researcher and Project Leader Viale Druso 1, I-39100 Bolzano t +39 0471 055 328 f +39 0471 055 429 [email protected] Peter Laner GIS Expert Viale Druso 1, I-39100 Bolzano t +39 0471 055 438 f +39 0471 055 429 [email protected] 2 European Regional Development Fund WP-T2 Regional Report: Val Passiria Contents 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 4 2 Methodology ........................................................................................................ 5 3 Val Passiria – Province of Bolzano/South Tyrol .................................................. 6 3.1 Socioeconomic framework of the region (D. 3.1.1) ........................................ 9 3.2 Demographic forecast (D. 3.3.1) ................................................................. 13 3.3 GIS maps visualising SGI accessibility (D. 3.6.1) ........................................ 18 3.3.1 Supermarket ........................................................................................ -

Elenco Definitivo Dei Rapporti Dormienti Al 31.05.2009

Elenco dei rapporti dormienti dal 01/06/2008 al 31/05/2009 Nome Cognome Data di Nascita Luogo di Nascita Provincia CAB Filiale Tipologia di rapporto Nr. Rapporto DOSOLINO BERTI 01/01/1919 CASTEL GOFFREDO MN 58590 Filiale Merano Conto Corrente 2029600 ANNA TROCKER 26/03/1933 RITTEN BZ 11601 Filiale Piazza Walther Libretto a risparmio nominativo 88916293 ANTON STAMPFL 01/02/1956 MERAN BZ 58590 Filiale Merano Libretto a risparmio nominativo 88916392 ARMIN ALTON 25/12/1986 SCHLANDERS BZ 58450 Agenzia Laces Libretto a risparmio nominativo 300377 BERNHARD ANTON LINTNER 23/09/1948 MELTINA BZ 58960 Agenzia Terlano Libretto a risparmio nominativo 88716292 BRIGITTE JUNGMANN 14/01/1961 STERZING BZ 58250 Agenzia Caldaro Libretto a risparmio nominativo 88916297 EVA CIBIEN 05/12/1993 BOLZANO BZ 11617 Agenzia Via Orazio Libretto a risparmio nominativo 390002 FRANZ GRUBER 09/05/1952 SARNTAL BZ 58870 Agenzia Sarentino Libretto a risparmio nominativo 88716297 GIUSEPPE GRAFF 17/07/1936 BRIXEN BZ 58220 Filiale Bressanone Libretto a risparmio nominativo 88716280 KLAUS REITER 10/07/1959 AUSTRIA INNSBRUCK EE 58210 Sportello Brennero Libretto a risparmio nominativo 88716288 LUDWIG PEDEVILLA 18/08/1921 ST.LORENZEN BZ 58240 Sede Brunico Libretto a risparmio nominativo 88916412 MANUEL DE LORENZO BUZZO 26/04/1993 BOLZANO BZ 11606 Filiale Via Resia Libretto a risparmio nominativo 5000369 MARIA LUISE WEIDENBRUECK 10/10/1926 GERMANIA EE 58960 Agenzia Terlano Libretto a risparmio nominativo 88916282 MARTIN IVISIC 04/04/1967 GERMANIA BRAUNSCHWEIG EE 58890 Agenzia Selva -

Information on Your Destination Hapimag Merano

Information on your destination Hapimag Merano Getting there Bus connections Munich main station to Merano. Every Saturday from the end of March to the beginning of November. Journey time of around 4 hours. Reservations in writing to the Merano management team, Freiheitsstrasse 35, 39012 Merano, Italy / [email protected]. South Tyrol Express, St. Gallen - Zurich – Merano. Every Saturday from April until the end of October. Journey time of around 4 hours. For more information, contact the Merano management team. Car Please note: in Merano, all districts are divided into coloured zones. The Hapimag Resort is located in the brown zone. Via the Passo di Resia (Reschenpass): on the carriageway to Merano city centre, take the exit for Merano/Marling. Follow the brown hotel route. The Hapimag resort is located in the Obermais district, Waalweg 18. If using a navigation system or route planner please enter the following destination address: Winkelweg 38, 39012 Merano. Via Bolzano: on the carriageway to Merano, take the exit for Bozen Süd. Take the Meran Süd (Sinich) exit and follow the brown hotel route. The Hapimag resort is located in the Obermais district, Waalweg 18. If using a navigation system or route planner please enter the following destination address: Winkelweg 38, 39012 Merano. Via the Passo di Monte Giovo (Jaufenpass): In Merano follow the brown hotel route. The Hapimag resort is located in the Obermais district, Waalweg 18. If using a navigation system or route planner please enter the following destination address: Winkelweg 38, 39012 Merano. Rail There are train connections from Austria and Germany to the Merano train station. -

Recapiti Degli Uffici Di Polizia Competenti in Materia

ALLOGGIATIWEB - COMUNI DELLA PROVINCIA DI BOLZANO - COMPETENZA TERRITORIALE ALLOGGIATIWEB - GEMEINDEN DER PROVINZ BOZEN - ÖRTLICHE ZUSTÄNDIGKEIT RECAPITI DEGLI UFFICI DI POLIZIA COMPETENTI ANSCHRIFTEN DER ZUSTÄNDIGEN POLIZEILICHEN ABTEILUNGEN IN MATERIA "ALLOGGIATIWEB" FÜR "ALLOGGIATIWEB" INFO POINT INFO POINT Questura di Bolzano Quästur Bozen Ufficio per le relazioni con il pubblico - URP Amt für die Beziehungen zur Öffentlichkeit - ABO Largo Giovanni Palatucci n. 1 Giovanni Palatucci Platz nr. 1 39100 Bolzano 39100 Bozen (BZ) Orario di apertura al pubblico: Lu-Ven 08.30-13.00 + Gio 15.00-17.00 Öffnungszeiten: Mon.-Fr. : 08.30 - 13.00 + Donn. 15.00-17.00 Tel.: 0471 947643 Tel.: 0471 947643 Questura di Bolzano Quästur Bozen P.A.S.I. - Affari Generali e Segreteria P.A.S.I (Verw.Pol.) - Allgemeine Angelegenheiten und Sekretariat Largo Giovanni Palatucci n. 1 Giovanni Palatucci Platz nr. 1 39100 Bolzano (BZ) 39100 Bozen (BZ) Orario di apertura al pubblico: Lu-Ven 08.30-13.00 Öffnungszeiten: Mon.-Fr. : 08.30 - 13.00 Tel.: 0471 947611 Tel.: 0471 947611 Pec: [email protected] Pec: [email protected] Commissariato di P. S. di Merano Polizeikommissariat Meran Polizia Amministrativa Verwaltungspolizei Piazza del Grano 1 Kornplatz 1 39012 Merano (BZ) 39012 Meran (BZ) Orario di apertura al pubblico: Lu-Ven 08.30-13.00 Öffnungszeiten: Mon.-Fr. : 08.30 - 13.00 Tel.: 0473 273511 Tel 0473 273511 Pec: [email protected] Pec: [email protected] Commissariato di P. S. di Bressanone Polizeikommissariat Brixen Polizia Amministrativa Verwaltungspolizei Via Vittorio Veneto 13 Vittorio Veneto Straße 13 39042 Bressanone (BZ) 39042 Brixen (BZ) Orario di apertura al pubblico: Lu-Ven 08.30-13.00 Öffnungszeiten: Mon.-Fr. -

Bavaria & the Tyrol

AUSTRIA & GERMANY Bavaria & the Tyrol A Guided Walking Adventure Table of Contents Daily Itinerary ........................................................................... 4 Tour Itinerary Overview .......................................................... 13 Tour Facts at a Glance ........................................................... 15 Traveling To and From Your Tour .......................................... 17 Information & Policies ............................................................ 20 Austria at a Glance ................................................................. 22 Germany at a Glance ............................................................. 26 Packing List ........................................................................... 31 800.464.9255 / countrywalkers.com 2 © 2015 Otago, LLC dba Country Walkers Travel Style This small-group Guided Walking Adventure offers an authentic travel experience, one that takes you away from the crowds and deep in to the fabric of local life. On it, you’ll enjoy 24/7 expert guides, premium accommodations, delicious meals, effortless transportation, and local wine or beer with dinner. Rest assured that every trip detail has been anticipated so you’re free to enjoy an adventure that exceeds your expectations. And, with our optional Flight + Tour ComboCombo,, Munich PrePre----TourTour Extension and Salzbug PostPost----TourTour Extension to complement this destination, we take care of all the travel to simplify the journey. Refer to the attached itinerary for more details. -

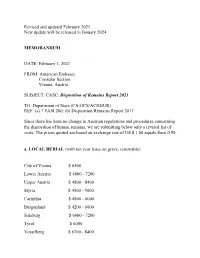

Disposition of Remains Report 2021

Revised and updated February 2021 New update will be released in January 2024 MEMORANDUM DATE: February 1, 2021 FROM: American Embassy Consular Section Vienna, Austria SUBJECT: CASC: Disposition of Remains Report 2021 TO: Department of State (CA/OCS/ACS/EUR) REF: (a) 7 FAM 260; (b) Disposition Remains Report 2017 Since there has been no change in Austrian regulations and procedures concerning the disposition of human remains, we are submitting below only a revised list of costs. The prices quoted are based on exchange rate of US $ 1.00 equals Euro 0.90. a. LOCAL BURIAL (with ten year lease on grave, renewable) City of Vienna $ 6500 Lower Austria $ 4800 - 7200 Upper Austria $ 4800 - 8400 Styria $ 4200 - 5000 Carinthia $ 4800 - 6000 Burgenland $ 4200 - 6000 Salzburg $ 6000 - 7200 Tyrol $ 6000 Vorarlberg $ 6700 - 8400 b. PREPARATION OF REMAINS FOR SHIPMENT TO THE UNITED STATES Vienna $ 6000 Lower Austria $ 6000 - 8900 Upper Austria $ 6000 - 8400 Styria $ 6000 - 8400 Carinthia $ 4800 - 6000 Burgenland $ 4800 - 7200 Salzburg $ 6000 Tyrol $ 6000 Vorarlberg $ 8900 c. COST OF SHIPPING PREPARED REMAINS TO THE UNITED STATES East Coast $ 2900 South Coast $ 2900 Central $ 2900 West Coast $ 3200 Shipping costs are based on an average weight of the casket with remains to be 150 kilos. d. CREMATION AND LOCAL BURIAL OF URN Vienna $ 5800 Lower Austria $ 9000 Upper Austria $ 3400 - 6700 Styria $ 4200 - 5000 Carinthia $ 5000 Burgenland $ 4200 - 5900 Salzburg (city) $ 4200 - 5900 Salzburg (province) $ 5500 Tyrol $ 5900 Vorarlberg $ 8400 e. CREMATION AND SHIPMENT OF URN TO THE UNITED STATES Vienna $ 3600 Lower Austria $ 4800 Upper Austria $ 3600 Styria $ 3600 Carinthia $ 4800 Burgenland $ 4800 Salzburg $ 3600 Tyrol $ 4200 Vorarlberg $ 6000 e. -

Fascist Legacies: the Controversy Over Mussolini’S Monuments in South Tyrol

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, Department of History History, Department of 2013 Fascist Legacies: The Controversy over Mussolini’s Monuments in South Tyrol Gerald Steinacher University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historyfacpub Steinacher, Gerald, "Fascist Legacies: The Controversy over Mussolini’s Monuments in South Tyrol" (2013). Faculty Publications, Department of History. 144. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historyfacpub/144 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Gerald Steinacher* Fascist Legacies:1 Th e Controversy over Mussolini’s Monuments in South Tyrol2 Th e northern Italian town of Bolzano (Bozen in German) in the western Dolomites is known for breathtaking natural landscapes as well as for its medieval city centre, gothic cathedral, and world-famous mummy, Ötzi the Iceman, which is on dis- play at the local archaeological museum. At the same time, Bolzano’s more recent history casts a shadow over the town. Th e legacy of fascism looms large in the form of Ventennio fascista-era monuments such as the Victory Monument, a mas- sive triumphal arch commissioned by the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini and located in Bolzano’s Victory Square, and the Mussolini relief on the façade of the former Fascist Party headquarters (now a tax offi ce) at Courthouse Square, which depicts il duce riding a horse with his arm raised high in the Fascist salute.