Possible Lessons from South Tyrol for Young Democracies on Ways to Protect Ethnic Minorities at a Regional Level

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The North-South Divide in Italy: Reality Or Perception?

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk EUROPEAN SPATIAL RESEARCH AND POLICY Volume 25 2018 Number 1 http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/1231-1952.25.1.03 Dario MUSOLINO∗ THE NORTH-SOUTH DIVIDE IN ITALY: REALITY OR PERCEPTION? Abstract. Although the literature about the objective socio-economic characteristics of the Italian North- South divide is wide and exhaustive, the question of how it is perceived is much less investigated and studied. Moreover, the consistency between the reality and the perception of the North-South divide is completely unexplored. The paper presents and discusses some relevant analyses on this issue, using the findings of a research study on the stated locational preferences of entrepreneurs in Italy. Its ultimate aim, therefore, is to suggest a new approach to the analysis of the macro-regional development gaps. What emerges from these analyses is that the perception of the North-South divide is not consistent with its objective economic characteristics. One of these inconsistencies concerns the width of the ‘per- ception gap’, which is bigger than the ‘reality gap’. Another inconsistency concerns how entrepreneurs perceive in their mental maps regions and provinces in Northern and Southern Italy. The impression is that Italian entrepreneurs have a stereotyped, much too negative, image of Southern Italy, almost a ‘wall in the head’, as also can be observed in the German case (with respect to the East-West divide). Keywords: North-South divide, stated locational preferences, perception, image. 1. INTRODUCTION The North-South divide1 is probably the most known and most persistent charac- teristic of the Italian economic geography. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The life and the autobiographical poetry of Oswald von Wolkenstein Robertshaw, Alan Thomas How to cite: Robertshaw, Alan Thomas (1973) The life and the autobiographical poetry of Oswald von Wolkenstein, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7935/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk THE LIFE AND THE AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL POETRY OF OSWALD VON WOLKENSTEIN Thesis submitted to the University of Durham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Alan Thomas Robertshaw, B»A. Exeter, March, 1973 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. CONTENTS Chapter Page Acknowledgements i Abstract ii Abbreviations iv I, INTRODUCTION 1 1o Summary of Research 1 20 Beda -

Socio-Cultural Characters of a Border Territory

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Volume 7 • Number 5 • May 2017 Socio-Cultural Characters of a Border Territory Marco Della Rocca Polytechnic of Turin Department Architectural Design Turin, Italy Abstract It is the aim of this article to analyze the political system in effect at the end of the XIX century in a border territory, such as Trentino Alto Adige, a region straddling to worlds: the Italian and the German speaking one. In this analysis I will retrace the origins of regional autonomy by recalling the historical and political events that let to a deep imprint of the concept of self-governance in this area; starting from the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the same year of the annexation of the Bishopric of Trento to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and until the outbreak of WWI. The aim of this study is to understand how deeply the forms of self-governance that the Austrian empire granted to the area influenced the culture and society of the time, and even left traces in today's modern society. 1. Introduction Autonomy is an intrinsic value in the Trentino Alto Adige region, inherited from the history of its past. «The political-administrative system of a State and the correlative concept of sovereignty» hail from its «development processes»; in the case of the Trento society it was the XIX century Hapsburg domination to deeply imprint the concept of «self-governance». The Austro-Hungarian Empire had expanded geographically through «territorial conquests thanks to hereditary rights or free loyalties as in the case of the county of Tyrol». -

Northern Italy: the Alps, Dolomites & Lombardy 2021

YOUR O.A.T. ADVENTURE TRAVEL PLANNING GUIDE® Northern Italy: The Alps, Dolomites & Lombardy 2021 Small Groups: 8-16 travelers—guaranteed! (average of 13) Overseas Adventure Travel ® The Leader in Personalized Small Group Adventures on the Road Less Traveled 1 Dear Traveler, At last, the world is opening up again for curious travel lovers like you and me. And the O.A.T. Northern Italy: The Alps, Dolomites & Lombardy itinerary you’ve expressed interest in will be a wonderful way to resume the discoveries that bring us so much joy. You might soon be enjoying standout moments like these: In my mind, nothing is more idyllic than the mountainous landscapes and rural villages of Alpine Europe. To immerse myself in their pastoral traditions and everyday life, I love to explore rural communities like Teglio, a small village nestled in the Valtellina Valley. You’ll see what I mean when you experience A Day in the Life of a small, family-run farm here where you’ll have the opportunity to meet the owner, walk the grounds, lend a hand with the daily farm chores, and share a traditional meal with your hosts in the farmhouse. You’ll also get a taste for some of the other crafts in the Valley when you visit a locally-owned goat cheese producer and a water-powered mill. But the most moving stories of all were the ones I heard directly from the local people I met. You’ll meet them, too, and hear their personal experiences during a conversation with two political refugeees at a local café in Milan to discuss the deeply divisive issue of immigration in Italy. -

Economic Geography and Its Effect on the Development of the German

Economic Geography and its Effect on the Development of the German States from the Holy Roman Empire to the German Zollverein (Wirtschaftsgeographie und ihr Einfluss auf die Entwicklung der deutschen Staaten vom Heiligen Romischen¨ Reich bis zum Deutschen Zollverein) DISSERTATION zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor rerum politicarum (Doktor der Wirtschaftswissenschaft) eingereicht an der WIRTSCHAFTSWISSENSCHAFTLICHEN FAKULTAT¨ DER HUMBOLDT-UNIVERSITAT¨ ZU BERLIN von THILO RENE´ HUNING M.SC. Pr¨asidentin der Humboldt-Universit¨at zu Berlin: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Dr. Sabine Kunst Dekan der Wirtschaftwissenschaftlichen Fakult¨at: Prof. Dr. Daniel Klapper Gutachter: 1. Prof. Dr. Nikolaus Wolf 2. Prof. Barry Eichengreen, Ph.D. Tag des Kolloqiums: 02. Mai 2018 Zusammenfassung Die vorliegende Dissertation setzt sich mit dem Einfluß okonomischer¨ Geographie auf die Geschichte des Heiligen Romischen¨ Reichs deutscher Nation bis zum Deutschen Zollverein auseinander. Die Dissertation besteht aus drei Kapiteln. Im ersten Kapitel werden die Effekte von Heterogenitat¨ in der Beobacht- barkeit der Bodenqualitat¨ auf Besteuerung und politischen Institutionen erlautert,¨ theoretisch betrachtet und empirisch anhand von Kartendaten analysiert. Es wird ein statistischer Zusammenhang zwischen Beobachtbarkeit der Bodenqualitat¨ und Große¨ und Uberlebenswahrschenlichkeit¨ von mittelalterlichen Staaten hergestelt. Das zweite Kapitel befasst sich mit dem Einfluß dieses Mechanismus auf die spezielle Geschichte Brandenburg-Preußens, und erlautert¨ die Rolle der Beobachtbarkeut der Bodenqualitat¨ auf die Entwicklung zentraler Institutionen nach dem Dreißigjahrigen¨ Krieg. Im empirischen Teil wird anhand von Daten zu Provinzkontributionen ein statistisch signifikanter Zusammenhang zwischen Bodenqualitat¨ und Besteuerug erst im Laufe des siebzehnten Jahrhundert deutlich. Das dritte Kapitel befasst sich mit dem Einfluß relativer Geographie auf die Grundung¨ des Deutschen Zollvereins als Folge des Wiener Kongresses. -

Bavaria & the Tyrol

AUSTRIA & GERMANY Bavaria & the Tyrol A Guided Walking Adventure Table of Contents Daily Itinerary ........................................................................... 4 Tour Itinerary Overview .......................................................... 13 Tour Facts at a Glance ........................................................... 15 Traveling To and From Your Tour .......................................... 17 Information & Policies ............................................................ 20 Austria at a Glance ................................................................. 22 Germany at a Glance ............................................................. 26 Packing List ........................................................................... 31 800.464.9255 / countrywalkers.com 2 © 2015 Otago, LLC dba Country Walkers Travel Style This small-group Guided Walking Adventure offers an authentic travel experience, one that takes you away from the crowds and deep in to the fabric of local life. On it, you’ll enjoy 24/7 expert guides, premium accommodations, delicious meals, effortless transportation, and local wine or beer with dinner. Rest assured that every trip detail has been anticipated so you’re free to enjoy an adventure that exceeds your expectations. And, with our optional Flight + Tour ComboCombo,, Munich PrePre----TourTour Extension and Salzbug PostPost----TourTour Extension to complement this destination, we take care of all the travel to simplify the journey. Refer to the attached itinerary for more details. -

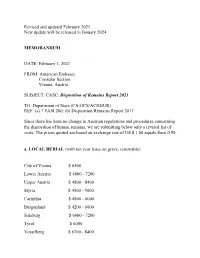

Disposition of Remains Report 2021

Revised and updated February 2021 New update will be released in January 2024 MEMORANDUM DATE: February 1, 2021 FROM: American Embassy Consular Section Vienna, Austria SUBJECT: CASC: Disposition of Remains Report 2021 TO: Department of State (CA/OCS/ACS/EUR) REF: (a) 7 FAM 260; (b) Disposition Remains Report 2017 Since there has been no change in Austrian regulations and procedures concerning the disposition of human remains, we are submitting below only a revised list of costs. The prices quoted are based on exchange rate of US $ 1.00 equals Euro 0.90. a. LOCAL BURIAL (with ten year lease on grave, renewable) City of Vienna $ 6500 Lower Austria $ 4800 - 7200 Upper Austria $ 4800 - 8400 Styria $ 4200 - 5000 Carinthia $ 4800 - 6000 Burgenland $ 4200 - 6000 Salzburg $ 6000 - 7200 Tyrol $ 6000 Vorarlberg $ 6700 - 8400 b. PREPARATION OF REMAINS FOR SHIPMENT TO THE UNITED STATES Vienna $ 6000 Lower Austria $ 6000 - 8900 Upper Austria $ 6000 - 8400 Styria $ 6000 - 8400 Carinthia $ 4800 - 6000 Burgenland $ 4800 - 7200 Salzburg $ 6000 Tyrol $ 6000 Vorarlberg $ 8900 c. COST OF SHIPPING PREPARED REMAINS TO THE UNITED STATES East Coast $ 2900 South Coast $ 2900 Central $ 2900 West Coast $ 3200 Shipping costs are based on an average weight of the casket with remains to be 150 kilos. d. CREMATION AND LOCAL BURIAL OF URN Vienna $ 5800 Lower Austria $ 9000 Upper Austria $ 3400 - 6700 Styria $ 4200 - 5000 Carinthia $ 5000 Burgenland $ 4200 - 5900 Salzburg (city) $ 4200 - 5900 Salzburg (province) $ 5500 Tyrol $ 5900 Vorarlberg $ 8400 e. CREMATION AND SHIPMENT OF URN TO THE UNITED STATES Vienna $ 3600 Lower Austria $ 4800 Upper Austria $ 3600 Styria $ 3600 Carinthia $ 4800 Burgenland $ 4800 Salzburg $ 3600 Tyrol $ 4200 Vorarlberg $ 6000 e. -

Fascist Legacies: the Controversy Over Mussolini’S Monuments in South Tyrol

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, Department of History History, Department of 2013 Fascist Legacies: The Controversy over Mussolini’s Monuments in South Tyrol Gerald Steinacher University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historyfacpub Steinacher, Gerald, "Fascist Legacies: The Controversy over Mussolini’s Monuments in South Tyrol" (2013). Faculty Publications, Department of History. 144. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historyfacpub/144 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Gerald Steinacher* Fascist Legacies:1 Th e Controversy over Mussolini’s Monuments in South Tyrol2 Th e northern Italian town of Bolzano (Bozen in German) in the western Dolomites is known for breathtaking natural landscapes as well as for its medieval city centre, gothic cathedral, and world-famous mummy, Ötzi the Iceman, which is on dis- play at the local archaeological museum. At the same time, Bolzano’s more recent history casts a shadow over the town. Th e legacy of fascism looms large in the form of Ventennio fascista-era monuments such as the Victory Monument, a mas- sive triumphal arch commissioned by the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini and located in Bolzano’s Victory Square, and the Mussolini relief on the façade of the former Fascist Party headquarters (now a tax offi ce) at Courthouse Square, which depicts il duce riding a horse with his arm raised high in the Fascist salute. -

Butlers of the Mohawk Valley: Family Traditions and the Establishment of British Empire in Colonial New York

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE December 2015 Butlers of the Mohawk Valley: Family Traditions and the Establishment of British Empire in Colonial New York Judd David Olshan Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Olshan, Judd David, "Butlers of the Mohawk Valley: Family Traditions and the Establishment of British Empire in Colonial New York" (2015). Dissertations - ALL. 399. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/399 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract: Butlers of the Mohawk Valley: Family Traditions and the Establishment of British Empire in Colonial New York Historians follow those tributaries of early American history and trace their converging currents as best they may in an immeasurable river of human experience. The Butlers were part of those British imperial currents that washed over mid Atlantic America for the better part of the eighteenth century. In particular their experience reinforces those studies that recognize the impact that the Anglo-Irish experience had on the British Imperial ethos in America. Understanding this ethos is as crucial to understanding early America as is the Calvinist ethos of the Massachusetts Puritan or the Republican ethos of English Wiggery. We don't merely suppose the Butlers are part of this tradition because their story begins with Walter Butler, a British soldier of the Imperial Wars in America. -

February 2011

Amber Road Tours Small group journeys through the best bits of Italy Life In Italy February Newsletter 2011 A Real Cold Case 2011 He was 45 years old, still tough but not exactly in his prime. Available Tours Once a village leader he was now on the run. His bow was Sicily broken and his arrows spent. He began carving new ones Oct 20-31 but his pursuers caught up with him too soon. He initially Week In Tuscany fought them with dagger hand-to-hand but being out- July 3-9 numbered sought to escape. Brought down by an arrow Sept 4-10 to his left shoulder (separating a major artery) he fell into a deep gully. Left dead and forgotten for… Tuscany/Umbria Sept 8-20 …five thousand years until two hikers discovered a frozen, Sept 22-Oct 4 fully clothed human corpse in the Italian Alps. An Austrian Oct 6-18 rescue team extracted the mummy from the ice and Tuscany/Liguria transported it to forensic scientists in Innsbruck. Initially June 8-16 thought to be a decade-old victim of a mountaineering accident the Iceman was Aug 31-Sept 8 determined to have been born sometime between the 33rd and the 31st centuries BC, Sept 14-22 predating the Egyptian pyramids! Oct 5-13 Amalfi/Puglia Archeologists excavated the site and discovered leather remains of a kit, a bearskin Sept 23-Oct 5 cap, a copper axe, dagger and a broken longbow. Such a well-preserved find had Oct 7-19 never been seen before and caused a world-wide sensation. -

Trentino, South Tyrol & the Dolomites

NO SINGLE SUPPLEMENT for Solo Travelers LAND SMALL GROUP JO URNEY Ma xi mum of 24 Travele rs Trentino, South Tyrol & the Dolomites Undiscovered Italy Inspiring Moments > Be captivated by the extraordinary beauty of the Dolomites, a canvas of snow- dusted peaks, spectacular rock formations and cascading emerald vineyards. > Discover an idyllic clutch of pretty piazzas, INCLUDED FEATURES serene parks and an ancient Roman arena in the setting for Accommodations (with baggage handling) Itinerary romantic Verona, – 7 nights in Trento, Italy, at the first-class Day 1 Depart gateway city Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet.” Grand Hotel Trento. Day 2 Arrive in Verona and transfer > Cruise Lake Garda, ringed by vineyards, to hotel in Trento lemon gardens and attractive harbors. Extensive Meal Program > From polenta to strudel to savory bread – 7 breakfasts, 3 lunches and 3 dinners, Day 3 Trento including Welcome and Farewell Dinners; Day 4 Lake Molveno | Madonna di dumplings known as canederli, dine on tea or coffee with all meals, plus wine Campiglio | Adamello-Brenta traditional dishes of northeastern Italy. with dinner. Nature Park > Relax over a delicious lunch at a chalet Day 5 Verona surrounded by breathtaking vistas. Your One-of-a-Kind Journey > Explore the old-world charm of Bolzano, – Discovery excursions highlight the local Day 6 Ortisei | Bolzano culture, heritage and history. Day 7 Limone sul Garda | Lake Garda | with its enticing blend of German and Italian cultures. – Expert-led Enrichment programs Malcensine enhance your insight into the region. Day 8 Trento > Experience two UNESCO World Heritage sites. – AHI Sustainability Promise: Day 9 Transfer to Verona airport We strive to make a positive, purposeful and depart for gateway city impact in the communities we visit. -

SOUTH TYROL in COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE1 Stefan Wolff I. Introduction the Instituti

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN COMPLEX POWER SHARING AS CONFLICT RESOLUTION: SOUTH TYROL IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE1 Stefan Wolff I. Introduction Th e institutional arrangements for South Tyrol draw on several traditional con- fl ict resolution techniques but also incorporate features that were novel in 1972 and have remained precedent-setting since then. First of all, South Tyrol can be described as a case of territorial self-governance; that is, “the legally entrenched power of ethnic or territorial communities to exercise public policy functions (legislative, executive and adjudicative) independently of other sources of author- ity in the state, but subject to the overall legal order of the state”.2 Th e forms such regimes can take include a wide range of institutional structures from enhanced local self-government to full-fl edged symmetrical or asymmetrical federal arrange- ments, as well as non-territorial (cultural or personal) autonomy. South Tyrol, in its specifi c Italian context, falls into the category of asymmetric arrangements in its relationship with the central government in Rome when compared to other Italian regions and provinces. However, it also comprises elements of non-territo- rial autonomy internally, especially in relation to the education system. Th ese non-territorial autonomy regimes fl ow from the application to South Tyrol of another well-known and relatively widely used confl ict resolution mechanism—consociational power sharing. Apart from the feature of ‘segmental autonomy’ (i.e., non-territorial autonomy for the two major ethnic groups in the province, primarily in the fi eld of education), South Tyrol also displays other 1 In this chapter I draw on previously published and ongoing research, including Stefan Wolff , “Territorial and Non-territorial Autonomy as Institutional Arrangements for the Settlement of Ethnic Confl icts in Mixed Areas”, in Andrew Dobson and Jeff rey Stanyer (eds.), Contemporary Political Studies 1998, Vol.