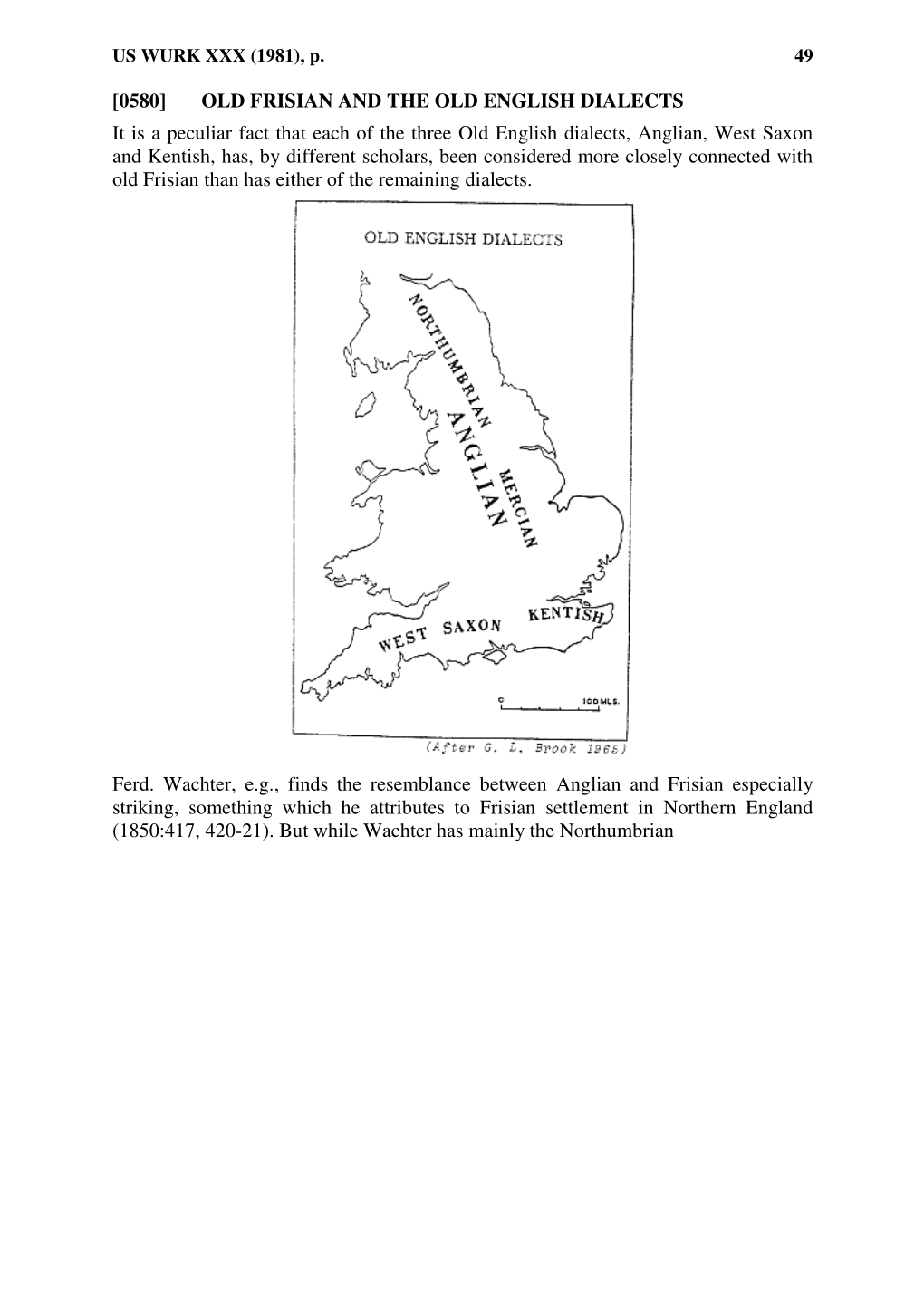

[0580] OLD FRISIAN and the OLD ENGLISH DIALECTS It Is a Peculiar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language Contact at the Romance-Germanic Language Border

Language Contact at the Romance–Germanic Language Border Other Books of Interest from Multilingual Matters Beyond Bilingualism: Multilingualism and Multilingual Education Jasone Cenoz and Fred Genesee (eds) Beyond Boundaries: Language and Identity in Contemporary Europe Paul Gubbins and Mike Holt (eds) Bilingualism: Beyond Basic Principles Jean-Marc Dewaele, Alex Housen and Li wei (eds) Can Threatened Languages be Saved? Joshua Fishman (ed.) Chtimi: The Urban Vernaculars of Northern France Timothy Pooley Community and Communication Sue Wright A Dynamic Model of Multilingualism Philip Herdina and Ulrike Jessner Encyclopedia of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism Colin Baker and Sylvia Prys Jones Identity, Insecurity and Image: France and Language Dennis Ager Language, Culture and Communication in Contemporary Europe Charlotte Hoffman (ed.) Language and Society in a Changing Italy Arturo Tosi Language Planning in Malawi, Mozambique and the Philippines Robert B. Kaplan and Richard B. Baldauf, Jr. (eds) Language Planning in Nepal, Taiwan and Sweden Richard B. Baldauf, Jr. and Robert B. Kaplan (eds) Language Planning: From Practice to Theory Robert B. Kaplan and Richard B. Baldauf, Jr. (eds) Language Reclamation Hubisi Nwenmely Linguistic Minorities in Central and Eastern Europe Christina Bratt Paulston and Donald Peckham (eds) Motivation in Language Planning and Language Policy Dennis Ager Multilingualism in Spain M. Teresa Turell (ed.) The Other Languages of Europe Guus Extra and Durk Gorter (eds) A Reader in French Sociolinguistics Malcolm Offord (ed.) Please contact us for the latest book information: Multilingual Matters, Frankfurt Lodge, Clevedon Hall, Victoria Road, Clevedon, BS21 7HH, England http://www.multilingual-matters.com Language Contact at the Romance–Germanic Language Border Edited by Jeanine Treffers-Daller and Roland Willemyns MULTILINGUAL MATTERS LTD Clevedon • Buffalo • Toronto • Sydney Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Language Contact at Romance-Germanic Language Border/Edited by Jeanine Treffers-Daller and Roland Willemyns. -

Saxony: Landscapes/Rivers and Lakes/Climate

Freistaat Sachsen State Chancellery Message and Greeting ................................................................................................................................................. 2 State and People Delightful Saxony: Landscapes/Rivers and Lakes/Climate ......................................................................................... 5 The Saxons – A people unto themselves: Spatial distribution/Population structure/Religion .......................... 7 The Sorbs – Much more than folklore ............................................................................................................ 11 Then and Now Saxony makes history: From early days to the modern era ..................................................................................... 13 Tabular Overview ........................................................................................................................................................ 17 Constitution and Legislature Saxony in fine constitutional shape: Saxony as Free State/Constitution/Coat of arms/Flag/Anthem ....................... 21 Saxony’s strong forces: State assembly/Political parties/Associations/Civic commitment ..................................... 23 Administrations and Politics Saxony’s lean administration: Prime minister, ministries/State administration/ State budget/Local government/E-government/Simplification of the law ............................................................................... 29 Saxony in Europe and in the world: Federalism/Europe/International -

Official Standard of the Old English Sheepdog General Appearance: a Strong, Compact, Square, Balanced Dog

Page 1 of 2 Official Standard of the Old English Sheepdog General Appearance: A strong, compact, square, balanced dog. Taking him all around, he is profusely, but not excessively coated, thickset, muscular and able-bodied. These qualities, combined with his agility, fit him for the demanding tasks required of a shepherd's or drover's dog. Therefore, soundness is of the greatest importance. His bark is loud with a distinctive "pot- casse" ring in it. Size, Proportion, Substance: Type, character and balance are of greater importance and are on no account to be sacrificed to size alone. Size - Height (measured from top of withers to the ground), Dogs: 22 inches (55.8 centimeters) and upward. Bitches: 21 inches (53.3 centimeters) and upward. Proportion - Length (measured from point of shoulder to point of ischium (tuberosity) practically the same as the height. Absolutely free from legginess or weaselness. Substance - Well muscled with plenty of bone. Head - A most intelligent expression. Eyes - Brown, blue or one of each. If brown, very dark is preferred. If blue, a pearl, china or wall-eye is considered typical. An amber or yellow eye is most objectionable. Ears - Medium sized and carried flat to the side of the head. Skull - Capacious and rather squarely formed giving plenty of room for brain power. The parts over the eyes (supra-orbital ridges) are well arched. The whole well covered with hair. Stop - Well defined. Jaw - Fairly long, strong, square and truncated. Attention is particularly called to the above properties as a long, narrow head or snipy muzzle is a deformity. -

Putting Frisian Names on the Map

GEGN.2/2021/68/CRP.68 15 March 2021 English United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names Second session New York, 3 – 7 May 2021 Item 12 of the provisional agenda * Geographical names as culture, heritage and identity, including indigenous, minority and regional languages and multilingual issues Putting Frisian names on the map Submitted by the Netherlands** * GEGN.2/2021/1 ** Prepared by Jasper Hogerwerf, Kadaster GEGN.2/2021/68/CRP.68 Introduction Dutch is the national language of the Netherlands. It has official status throughout the Kingdom of the Netherlands. In addition, there are several other recognized languages. Papiamentu (or Papiamento) and English are formally used in the Caribbean parts of the Kingdom, while Low-Saxon and Limburgish are recognized as non-standardized regional languages, and Yiddish and Sinte Romani as non-territorial minority languages in the European part of the Kingdom. The Dutch Sign Language is formally recognized as well. The largest minority language is (West) Frisian or Frysk, an official language in the province of Friesland (Fryslân). Frisian is a West Germanic language closely related to the Saterland Frisian and North Frisian languages spoken in Germany. The Frisian languages as a group are closer related to English than to Dutch or German. Frisian is spoken as a mother tongue by about 55% of the population in the province of Friesland, which translates to some 350,000 native speakers. In many rural areas a large majority speaks Frisian, while most cities have a Dutch-speaking majority. A standardized Frisian orthography was established in 1879 and reformed in 1945, 1980 and 2015. -

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR of OLD ENGLISH Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR OF OLD ENGLISH MEDievaL AND Renaissance Texts anD STUDies VOLUME 463 MRTS TEXTS FOR TEACHING VOLUme 8 An Introductory Grammar of Old English with an Anthology of Readings by R. D. Fulk Tempe, Arizona 2014 © Copyright 2020 R. D. Fulk This book was originally published in 2014 by the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Arizona State University, Tempe Arizona. When the book went out of print, the press kindly allowed the copyright to revert to the author, so that this corrected reprint could be made freely available as an Open Access book. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE viii ABBREVIATIONS ix WORKS CITED xi I. GRAMMAR INTRODUCTION (§§1–8) 3 CHAP. I (§§9–24) Phonology and Orthography 8 CHAP. II (§§25–31) Grammatical Gender • Case Functions • Masculine a-Stems • Anglo-Frisian Brightening and Restoration of a 16 CHAP. III (§§32–8) Neuter a-Stems • Uses of Demonstratives • Dual-Case Prepositions • Strong and Weak Verbs • First and Second Person Pronouns 21 CHAP. IV (§§39–45) ō-Stems • Third Person and Reflexive Pronouns • Verbal Rection • Subjunctive Mood 26 CHAP. V (§§46–53) Weak Nouns • Tense and Aspect • Forms of bēon 31 CHAP. VI (§§54–8) Strong and Weak Adjectives • Infinitives 35 CHAP. VII (§§59–66) Numerals • Demonstrative þēs • Breaking • Final Fricatives • Degemination • Impersonal Verbs 40 CHAP. VIII (§§67–72) West Germanic Consonant Gemination and Loss of j • wa-, wō-, ja-, and jō-Stem Nouns • Dipthongization by Initial Palatal Consonants 44 CHAP. IX (§§73–8) Proto-Germanic e before i and j • Front Mutation • hwā • Verb-Second Syntax 48 CHAP. -

H Kontakt \H 11' /F R Ve Gl Ich 1' UL-, Vanatlon Festschrift Fi.Ir Gottfried

kontakt ve gl�ich \h 11'/f r h � S1' UL-, vanatlon Festschrift fi.ir Gottfried Kolde zum 65. Geburtstag Herausgegeben von Kirsten Adamzik und Helen Christen Sonderdruck ISBN 3-484-73055-2 Max Niemeyer Verlag Tubingen 2001 l l_·-- Inhaltsverzeichnis Werner Abraham Negativ-polare Zeitangaben im Westgermanischen und die perfektive Kohasionsstrategie .. .. .. .. .. .. .. l Peter Blumenthal Deixis im literarisehen Text. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 11 BernhardBasebenstein Nominaldetermination im Deutschen und Franzosischen. Beobachtungen an zwei Gedichten und ihren modemen Obersetzungen (Rimbauds Bateauivre in Celans Fassung und Holderlins Ister in du Bouchets Version) .. .. .. ..... ..... ..... 31 Renate Basebenstein Lorenzos Wunde. Sprachgebung und psychologische Problematik in Thomas Manns Drama Fiorenza......................... ........... 39 Helen Christen l Anton Naf Trausers, shoues und Eis - Englisches im Deutsch von Franzosischsprachigen .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 61 Erika Diehl Wie sag ich's meinem Kinde? Modelle des Fremdsprachenunterrichts in der Primarschule am Beispiel Deutsch im Wallis und in Genf . .. .. 99 Jiirgen Dittmann Zum Zusammenhangvon Grammatik und Arbeitsgedachtnis. .. .. .. 123 Verena Ehrich-Haefeli Die Syntax des Begehrens. Zum Spntchwandel am Beginn der burgerliehen Moderne. Sophie La Roche: Geschichte des Frauleins von Sternheim, Goethe: Die Leiden desjungen Werther .......... ... 139 Karl-Ernst Geith Der lfp wandelt sich nach dem muot Zur nonverbalen Kommunikation im 'Rolandslied'.... ... ....... ... 171 -

United States National Museum

Q 11 U563 CRLSSI . e I ^ t UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM BULLETIN 218 Papers 1 to 11 Contributions FROM THE Museum OF History and Technology SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION O WASHINGTON. DC. ^ 1959 WS'n NOV 16 1959 ISSUED NOVl 61959 Smithsonian Institution UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM Remington Kellooo Director Smith, Director Trank a. Taylor, Director Albert C. Museum oj jXatural History Afiisfum of ///'A"V 'iiiil Tirhwiliniv Publications of the United States National Museum include two The scientific publications of the United Stales National Museum States National Museum scries, Proceedings oj the United States National Museum and United Bulletin. dealing with the In these series are published original articles and monographs facts in the collections and work of the Museum and setting forth newly acquired Copies of fields of Anthropolog)', Biology, Geolog)', History, and Technology. each publication are distributed to libraries and scientific organizations and to specialists and others interested in the dififerent subjects. separate The Proceedings, begun in 1878, are intended for the publication, in size, with the form, of shorter papers. These are gathered in volumes, octavo in publication date of each paper recorded in the taljle of contents of the volume. separate In the Bulletin series, the first of which was issued in 1875, appear longer, publications consisting of monographs (occasionally in several parts) and volumes either octavo or in which are collected works on related subjects. Bulletins are papers re- qiiarto in size, depending on the needs of the presentation. Since 1902 lating to the botanical collections of the Museum have been published in the Bulletin series under the heading Contributions Jrom the United Stales National Herbarium. -

"Ich Höre Gern Diesen Dialekt, Erinnert Mich an Meine Urlaube in Kärnten

"Ich höre gern diesen Dialekt, erinnert mich an meine Urlaube in Kärnten ... ": A survey of the usage and the popularity of Austrian dialects in Vienna John Bellamy (Manchester) A survey of over 200 Austrians was undertaken in Vienna to investigate the extent to which they say they use dialect. They were asked if they speak dialect and if they do, in which situations they would switch to using predominantly Hochsprache. The responses have been analysed according to age, gender, birthplace (in Austria) and occupation to find out if the data reveals underlying correlations, especially to see if there have been any developments of note since earlier studies (for example, Steinegger 1995). The same group of informants were also asked about their opinions of Austrian dialects in general and this paper details their answers along with the reasons behind their positive or negative responses in this regard. The data collected during this survey will be compared to other contemporary investigations (particularly Soukup 2009) in an effort to obtain a broader view of dialect usage and attitudes towards dialect in Vienna and its environs. Since a very similar study was undertaken at the same time in the UK (Manchester) with more or less the same questions, the opportunity presents itself to compare dialect usage in the area in and around Vienna with regional accents and usage in the urban area of Manchester. References will be made during the course of the presentation to both sets of data. Language planning in Europe during the long 19th century: The selection of the standard language in Norway and Flanders Els Belsack (VU Brussel) The long 19th century (1794-1914) is considered to be the century of language planning par excellence. -

Old Frisian, an Introduction To

An Introduction to Old Frisian An Introduction to Old Frisian History, Grammar, Reader, Glossary Rolf H. Bremmer, Jr. University of Leiden John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam / Philadelphia TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of 8 American National Standard for Information Sciences — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bremmer, Rolf H. (Rolf Hendrik), 1950- An introduction to Old Frisian : history, grammar, reader, glossary / Rolf H. Bremmer, Jr. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Frisian language--To 1500--Grammar. 2. Frisian language--To 1500--History. 3. Frisian language--To 1550--Texts. I. Title. PF1421.B74 2009 439’.2--dc22 2008045390 isbn 978 90 272 3255 7 (Hb; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 3256 4 (Pb; alk. paper) © 2009 – John Benjamins B.V. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. John Benjamins Publishing Co. · P.O. Box 36224 · 1020 me Amsterdam · The Netherlands John Benjamins North America · P.O. Box 27519 · Philadelphia pa 19118-0519 · usa Table of contents Preface ix chapter i History: The when, where and what of Old Frisian 1 The Frisians. A short history (§§1–8); Texts and manuscripts (§§9–14); Language (§§15–18); The scope of Old Frisian studies (§§19–21) chapter ii Phonology: The sounds of Old Frisian 21 A. Introductory remarks (§§22–27): Spelling and pronunciation (§§22–23); Axioms and method (§§24–25); West Germanic vowel inventory (§26); A common West Germanic sound-change: gemination (§27) B. -

Modeling a Historical Variety of a Low-Resource Language: Language Contact Effects in the Verbal Cluster of Early-Modern Frisian

Modeling a historical variety of a low-resource language: Language contact effects in the verbal cluster of Early-Modern Frisian Jelke Bloem Arjen Versloot Fred Weerman ILLC ACLC ACLC University of Amsterdam University of Amsterdam University of Amsterdam [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract which are by definition used less, and are less likely to have computational resources available. For ex- Certain phenomena of interest to linguists ample, in cases of language contact where there is mainly occur in low-resource languages, such as contact-induced language change. We show a majority language and a lesser used language, that it is possible to study contact-induced contact-induced language change is more likely language change computationally in a histor- to occur in the lesser used language (Weinreich, ical variety of a low-resource language, Early- 1979). Furthermore, certain phenomena are better Modern Frisian, by creating a model using studied in historical varieties of languages. Taking features that were established to be relevant the example of language change, it is more interest- in a closely related language, modern Dutch. ing to study a specific language change once it has This allows us to test two hypotheses on two already been completed, such that one can study types of language contact that may have taken place between Frisian and Dutch during this the change itself in historical texts as well as the time. Our model shows that Frisian verb clus- subsequent outcome of the change. ter word orders are associated with different For these reasons, contact-induced language context features than Dutch verb orders, sup- change is difficult to study computationally, and porting the ‘learned borrowing’ hypothesis. -

(In)Declinable Relative Pronoun and Its Syntactic Functions

It Beaken jiergong 77 – 2015 nr 3/4 165-174 A historical note on the (in)declinable relative pronoun and its syntactic functions Eric Hoekstra Summary The indeclinable relative particle of Old Germanic could be used for at least 3 syntactic functions: for the relativisation of (1) subjects, (2) objects and (3) preposi- tional complements, for example in Old English and Old Frisian. This is no longer the case in Modern English, Modern Dutch, Modern German or Modern Frisian. It is pointed out that the indeclinable relative particle retained all three functions in Frisian until around 1900, when it stopped being used for the relativisation of subjects and objects. All three functions were retained at least until the middle of the 20th century in the Dutch dialects of Marken and Volendam, which both border on the lake IJsselmeer as does the province of Fryslân. The indeclinable relative particle has been pushed back in Frisian by the declinable relative particle, a process which has its roots in Old Frisian. It is shown that the declinable relative particle (dy, dat in Frisian) has gradually taken over the function of subject and ob- ject relativisation. Historically, the indeclinable relative particle developed into the R-pronoun (Frisian dêr), and it is still used to relativize prepositional complements in Modern Frisian, thus retaining its third syntactic function. 1. Two types of relative pronouns It is the purpose of this article to establish that, for centuries now, Frisian distinguishes between two types of relative pronouns. One type of pronoun does not decline for gender, the other type does. -

For the Official Published Version, See Lingua 133 (Sept. 2013), Pp. 73–83. Link

For the official published version, see Lingua 133 (Sept. 2013), pp. 73–83. Link: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/00243841 External Influences on English: From its Beginnings to the Renaissance, D. Gary Miller, Oxford University Press (2012), xxxi + 317 pp., Price: £65.00, ISBN 9780199654260 Lexical borrowing aside, external influences are not the main concern of most histories of the English language. It is therefore timely, and novel, to have a history of English (albeit only up to the Renaissance period) that looks at English purely from the perspective of external influences. Miller assembles his book around five strands of influence: (1) Celtic, (2) Latin and Greek, (3) Scandinavian, (4) French, (5) later Latin and Greek input, and he focuses on influences that left their mark on contemporary mainstream English rather than on regional or international varieties. This review looks at all chapters, but priority is given to Miller’s discussions of structural influence, especially on English syntax, morphology and phonology, which often raise a number of theoretical issues. Loanwords from various sources, which are also covered extensively in the book, will receive slightly less attention. Chapter 1 introduces the Indo-European and Germanic background of English and gives short descriptions of the languages with which English came into contact. This is a good way to start the book, but the copious lists of loanwords from Norwegian, Swedish, Danish, German, Low German, Afrikaans etc., most of which appear in English long after the Renaissance stop-off point, were not central to its aims. It would have been better to use this space to expand upon the theoretical framework employed throughout the book.