Download Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Past Commissions 2014/15

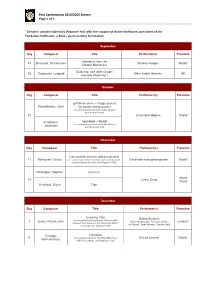

Past Commissions 2014/2015 Season Page 1 of 5 * Denotes commissioned by Wigmore Hall with the support of André Hoffmann, president of the Fondation Hoffmann, a Swiss grant-making foundation September Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Variations from the 14 Birtwistle, Sir Harrison Nicolas Hodges World* Golden Mountains Study No. 44A after Chopin 15 Godowsky, Leopold Marc-André Hamelin UK nouvelle étude No.1 October Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première gefährlich dünn — fragile pieces Petraškevičs, Jānis for double string quartet (co-commissioned by Ensemble Modern and Wigmore Hall) 10 Ensemble Modern World* Schöllhorn, sous-bois – Sextet (co-commissioned by Ensemble Modern Johannes and Wigmore Hall) November Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Carnaval for clarinet, piano and cello 11 Mantovani, Bruno (co-commissioned by Ensemble intercontemporain, Ensemble intercontemporain World* Opéra national de Paris and Wigmore Hall) Montague, Stephen nun-mul World 16 Jenna Sung World Pritchard, Gwyn Tide December Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Uncanny Vale Britten Sinfonia (co-commissioned by Britten Sinfonia with 3 Jones, Patrick John (Emer McDonough, Nicholas Daniel, London* support from donors to the Musically Gifted Joy Farrall, Sarah Burnett, Stephen Bell) campaign and Wigmore Hall) Turnage, Contusion 6 (co-commissioned by The Radcliffe Trust, Belcea Quartet World* Mark-Anthony NMC Recordings and Wigmore Hall) Past Commissions 2014/2015 Season Page 2 of 5 January Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Light and Matter Britten Sinfonia (co-commissioned by Britten Sinfonia with 14 Saariaho, Kaija (Jacqueline Shave, Caroline Dearnley, London* support from donors to the Musically Gifted campaign Huw Watkins) and Wigmore Hall) 3rd Quartet Holt, Simon (co-commissioned by The Radcliffe Trust, World* NMC Recordings, Heidelberger Frühling, and 19 Wigmore Hall) JACK Quartet Haas, Georg Friedrich String Quartet No. -

London Mozart Players Wind Trio When He Left to Focus on His Freelance Career

Timothy Lines (Clarinet) Timothy studied at the Royal College of Music with Michael Collins and now enjoys a wide- ranging career as a clarinettist. He has played with all the major symphony orchestras in London as well as with chamber groups including London Sinfonietta and the Nash Ensemble. From 1999 to 2003 he was Principal Clarinet of the London Symphony Orchestra and was also chairman of the orchestra during his last year there. From September 2004 to January 2006 he was section leader clarinet of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, London Mozart Players Wind Trio when he left to focus on his freelance career. He plays on original instruments with the English Baroque Soloists, the Orchestre Revolutionnaire et Romantique and the Orchestra of Thursday 12th March 2020 at 7.30 pm the Age of Enlightenment and is also frequently engaged to record film music and pop music Cavendish Hall, Edensor tracks. Timothy is Professor of Clarinet at both the Royal College of Music and the Royal Academy of Music, and is the clarinet coach for the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain. In March 2016 he was awarded a Fellowship of the Royal College of Music and was later that year invited to become Principal Clarinet of the London Mozart Players. Concert Champêtre H. TOMASI Gareth Hulse (Oboe) (1901-1971) After reading music at Cambridge, Gareth Hulse studied with Janet Craxton at the Royal Divertimento K439b W.A. MOZART Academy of Music, and with Heinz Holliger at the Freiburg Hochschule fur Musik. On his (1756-1791) return to England he was appointed Principal Oboe with the Northern Sinfonia, a position he has since held with English National Opera and the London Philharmonic. -

November 2016

November 2016 Igor Levit INSIDE: Borodin Quartet Le Concert d’Astrée & Emmanuelle Haïm Imogen Cooper Iestyn Davies & Thomas Dunford Emerson String Quartet Ensemble Modern Brigitte Fassbaender Masterclasses Kalichstein/Laredo/ Robinson Trio Dorothea Röschmann Sir András Schiff and many more Box Office 020 7935 2141 Online Booking www.wigmore-hall.org.uk How to Book Wigmore Hall Box Office 36 Wigmore Street, London W1U 2BP In Person 7 days a week: 10 am – 8.30 pm. Days without an evening concert 10 am – 5 pm. No advance booking in the half hour prior to a concert. By Telephone: 020 7935 2141 7 days a week: 10 am – 7 pm. Days without an evening concert 10 am – 5 pm. There is a non-refundable £3.00 administration fee for each transaction, which includes the return of your tickets by post if time permits. Online: www.wigmore-hall.org.uk 7 days a week; 24 hours a day. There is a non-refundable £2.00 administration charge. Standby Tickets Standby tickets for students, senior citizens and the unemployed are available from one hour before the performance (subject to availability) with best available seats sold at the lowest price. NB standby tickets are not available for Lunchtime and Coffee Concerts. Group Discounts Discounts of 10% are available for groups of 12 or more, subject to availability. Latecomers Latecomers will only be admitted during a suitable pause in the performance. Facilities for Disabled People full details available from 020 7935 2141 or [email protected] Wigmore Hall has been awarded the Bronze Charter Mark from Attitude is Everything TICKETS Unless otherwise stated, tickets are A–D divided into five prices ranges: BALCONY Stalls C – M W–X Highest price T–V Stalls A – B, N – P Q–S 2nd highest price Balcony A – D N–P 2nd highest price STALLS Stalls BB, CC, Q – S C–M 3rd highest price A–B Stalls AA, T – V CC CC 4th highest price BB BB PLATFORM Stalls W – X AAAA AAAA Lowest price This brochure is available in alternative formats. -

Download Booklet

C M Y B The Nash Ensemble Sally Matthews C M C M Y B www.onyxclassics.com ONYX 4005 Y B TURNAGE THIS SILENCE p1 Eulogy p12 Two Baudelaire Songs Cantilena Slide Stride PAGE XX12 PAGE 01 C M Y B C M Y B MARK-ANTHONY TURNAGE (1960-) Chamber Works This Silence for Octet (1992-3) 1 Dance 8.21 2 Dirge 7.14 True Life Stories for solo piano (1995-9) 3 Elegy for Andy 3.28 4 William’s Pavane 1.37 5 Song for Sally 2.35 6 Edward’s refrain 3.12 7 Tune for Toru 2.04 C M C M Y B 8 Slide Stride for piano and string quartet (2002) 13.02 Y B Two Baudelaire Songs for soprano and seven instruments (2004) p11 9 Harmonie du Soir 5.51 10 L’invitation au voyage 4.32 p2 11 Eulogy for viola and eight instruments (2003) 9.56 Two Vocalises for cello and piano (2002) Executive Producer: Chris Craker 12 Maclaren’s farewell 3.08 Producer & Engineer: Chris Craker 13 Vocalise 2.32 Post-Production: Simon Haram Mastered by: Chris Craker and Simon Haram 14 Cantilena for oboe and string quartet (2001) 10.45 Recording Location: Henry Wood Hall, London, 24-26 October 2004 Publishers: Schott Musik International [1-8], [12-14], Boosey & Hawkes Ltd [9-11] Total Time 78.34 Product Director: Paul Moseley Cover photograph © Hanya Chlala/Arena PAL Design: CEH PAGE 02 PAGE 11 C M Y B C M Y B L’invitation au voyage Invitation to the voyage Mon enfant, ma soeur, My child, my sister, Songe à la douceur Think of the rapture D'aller là-bas vivre ensemble! Of living together there! Aimer à loisir, Of loving at will, Aimer et mourir Of loving till death, Au pays qui te ressemble! In the land that is like you! Les soleils mouillés The misty sunlight De ces ciels brouillés Of those cloudy skies Pour mon esprit ont les charmes Has for my spirit the charms, Si mystérieux So mysterious, De tes traîtres yeux, Of your treacherous eyes, Brillant à travers leurs larmes. -

The Perfect Pitch 2012

2012 2011–2012 Javier Alvarez, Composer Samuel Ramey, Bass-Baritone Peter Bagley, Conductor Sandra Rivers, Piano Jay Batzner, Composer Gail Robertson, Euphonium Shawn Bell Quartet Christine Salerno and ZIJI Fred Hersch, Piano and Composer Justin Benavidez, Tuba Mauricio Salguero, Clarinet Janet Hilton, Clarinet Gene Bertoncini, Guitar John Sampen, Saxophone Edith Hines, Baroque Violin Alex Brown, Piano San Francisco Jazz Collective Jon Holden, Clarinet Mark Bunce, Composer and Engineer Nina Schumann and Lúis Magalháes, Piano Pat Hughes, Horn Roger Chase, Viola Dan Scott, String Education Specialist Naoko Imafuku, Piano Larry Clark, Conductor Kendrick Scott, Drums JaLaLa Evan Conroy, Bass Trombone Mira Shifrin, Flute Lia Jensen-Abbott, Piano Mike Crotty, Multi-instrumentalist Alan Siebert, Trumpet Mayumi Kanagawa, Violin Vocal Coach and Piano Composer Vera Danchenko-Stern, (Stulberg Silver Medalist) Mark Snyder, Joel Davel, Percussion Jack Stamp, Conductor and Composer Christopher Kantner, Flute The Quincy Davis Project Elizabeth Start, Cello Kontras String Quartet Alissa Deeter, Soprano John Chappell Stowe, Organ and Harpsichord Massimo LaRosa, Trombone Detroit Symphony Orchestra Brass Players Mihai Tetel, Cello Dan Levitin, Neuroscientist Piano Piano Ron DiSalvio, and Cognitive Psychologist Yu-Lien The, Paquito D’Rivera, Clarinet, Saxophone, Walter Thompson, Soundpainter and Composer The Dave Liebman Group and Composer Trollstilt Andrew List, Composer John Duykers, Tenor Dan Trueman, Composer Paul Loesel, Piano and Composer Euclid Quartet -

2016/17 Season Preview and Appeal

2016/17 SEASON PREVIEW AND APPEAL The Wigmore Hall Trust would like to acknowledge and thank the following individuals and organisations for their generous support throughout the THANK YOU 2015/16 Season. HONORARY PATRONS David and Frances Waters* Kate Dugdale A bequest from the late John Lunn Aubrey Adams David Evan Williams In memory of Robert Easton David Lyons* André and Rosalie Hoffmann Douglas and Janette Eden Sir Jack Lyons Charitable Trust Simon Majaro MBE and Pamela Majaro MBE Sir Ralph Kohn FRS and Lady Kohn CORPORATE SUPPORTERS Mr Martin R Edwards Mr and Mrs Paul Morgan Capital Group The Eldering/Goecke Family Mayfield Valley Arts Trust Annette Ellis* Michael and Lynne McGowan* (corporate matched giving) L SEASON PATRONS Clifford Chance LLP The Elton Family George Meyer Dr C A Endersby and Prof D Cowan Alison and Antony Milford L Aubrey Adams* Complete Coffee Ltd L American Friends of Wigmore Hall Duncan Lawrie Private Banking The Ernest Cook Trust Milton Damerel Trust Art Mentor Foundation Lucerne‡ Martin Randall Travel Ltd Caroline Erskine The Monument Trust Karl Otto Bonnier* Rosenblatt Solicitors Felicity Fairbairn L Amyas and Louise Morse* Henry and Suzanne Davis Rothschild Mrs Susan Feakin Mr and Mrs M J Munz-Jones Peter and Sonia Field L A C and F A Myer Dunard Fund† L The Hargreaves and Ball Trust BACK OF HOUSE Deborah Finkler and Allan Murray-Jones Valerie O’Connor Pauline and Ian Howat REFURBISHMENT SUMMER 2015 Neil and Deborah Franks* The Nicholas Boas Charitable Trust The Monument Trust Arts Council England John and Amy Ford P Parkinson Valerie O’Connor The Foyle Foundation S E Franklin Charitable Trust No. -

2018/19 Season

MARCH 2018/19 Season wigmore-hall.org.uk 2 • SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER wigmore-hall.org.uk How to Book Wigmore Hall Box Office TICKETS 36 Wigmore Street, London W1U 2BP Unless otherwise stated, tickets are divided into five price ranges: In Person ■ Stalls C – M Highest price 7 days a week: 10.00am - 8.30pm. ■ Stalls A – B, N – P 2nd highest price Days without an evening concert: ■ Balcony A – D 2nd highest price 10.00am - 5.00pm. No advance booking in the ■ Stalls BB, CC, Q – S 3rd highest price half hour prior to a concert. ■ Stalls AA, T – V 4th highest price ■ Stalls W – X Lowest price By Telephone: 020 7935 2141 7 days a week: 10.00am - 7.00pm. AA AA Days without an evening concert: AA STAGE AA AA AA 10.00am - 5.00pm. BB BB There is a non-refundable £4.00 administration CC CC A A charge for each transaction. B B C C D D Online: wigmore-hall.org.uk E E F FRONT FRONT F STALLS STALLS 7 days a week; 24 hours a day. There is a G G non-refundable £3.00 administration charge. H H I I J J K K Standby Tickets L L M M Standby tickets for students, senior citizens and N N the unemployed are available from one hour O O P P before the performance (subject to availability) Q Q with best available seats sold at the lowest price. R R S S REAR REAR NB standby tickets are not available for T STALLS STALLS T U U Lunchtime and Sunday Morning Concerts. -

THE NASH ENSEMBLE of LONDON Amelia Freedman CBE, Artistic Director

THURSDAY, APRIL 3, 2014 AT 8:00PM Richardson Auditorium in Alexander Hall Musical Preview by Princeton pianists Paul von Autenried ‘16, Darya Koltunyuk ‘15 and Edward Leung ’16 at 7pm THE NASH ENSEMBLE OF LONDON Amelia Freedman CBE, Artistic Director Ian Brown, Piano • Philippa Davies, Flute • Richard Hosford, Clarinet Stephanie Gonley, Violin • Laura Samuel, Violin Lawrence Power, Viola • Rebecca Gilliver, Cello Bedrichˇ SMETANA Overture to The Bartered Bride for Piano, Flute,Clarinet and String Quartet (arr. David Matthews) BROWN, DAVIES, HOSFORD, GONLEY, SAMUEL, POWER, GILLIVER Viet CUONG Trains of Thought (World Premiere) BROWN, DAVIES, HOSFORD, GONLEY, SAMUEL, POWER, GILLIVER Robert SCHUMANN Märchenerzählungen (“Fairy Tales”) for Clarinet, Viola and Piano, Op.132 Lebhaft, nicht zu schnell Lebhaft und sehr markiert Ruhiges Tempo, mit zartem Ausdruck Lebhaft, sehr markiet HOSFORD, POWER, BROWN Q INTERMISSION Q Dmitri SHOSTAKOVICH Four Waltzes for Flute, Clarinet and Piano Spring Waltz Waltz-Joke Waltz Barrel-Organ Waltz DAVIES, HOSFORD, BROWN Antonín DVORÁKˇ Quintet for Piano and Strings in A Major, Op. 81 Allegro, ma non tanto Dumka: Andante con moto Scherzo (Furiant) – molto vivace Finale: Allegro BROWN, GONLEY, SAMUEL, POWER, GILLIVer Please join us briefly following the performance for a post-concert Talk Back moderated by Professor Dan Trueman. ABOUT THE ARTISTS PRINCETON UNIVERSITY CONCERTS 2013-14 SEASON ABOUT THE NASH ENSEMBLE OF LONDON The Nash Ensemble has built a remarkable reputation as one of Britain’s finest and most adventurous chamber groups, and through the dedication of its founder and Artistic Director Amelia Freedman and the caliber of its players, has gained a similar reputation all over the world. -

Pdf Download the March 2020 Diary

MARCH 2019/20 SEASON wigmore-hall.org.uk 2 • SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER wigmore-hall.org.uk How to Book Wigmore Hall Box Office TICKETS 36 Wigmore Street, London W1U 2BP Unless otherwise stated, tickets are divided into five price ranges: In Person ■ Stalls C – M Highest price 7 days a week: 10.00am - 8.30pm. ■ Stalls A – B, N – P 2nd highest price Days without an evening concert: ■ Balcony A – D 2nd highest price 10.00am - 5.00pm. No advance booking in the ■ Stalls BB, CC, Q – S 3rd highest price half hour prior to a concert. ■ Stalls AA, T – V 4th highest price ■ Stalls W – X Lowest price By Telephone: 020 7935 2141 7 days a week: 10.00am - 7.00pm. AA AA Days without an evening concert: AA STAGE AA AA AA 10.00am - 5.00pm. BB BB There is a non-refundable £4.00 administration CC CC A A charge for each transaction. B B C C D D Online: wigmore-hall.org.uk E E F FRONT FRONT F STALLS STALLS 7 days a week; 24 hours a day. There is a G G non-refundable £3.00 administration charge. H H I I J J K K Standby Tickets L L M M Standby tickets for students, senior citizens and N N the unemployed are available from one hour O O P P before the performance (subject to availability) Q Q with best available seats sold at the lowest price. R R S S REAR REAR NB standby tickets are not available for T STALLS STALLS T U U Lunchtime and Sunday Morning Concerts. -

The Clarinetist's Guide to the Performance of the Clarinet, Viola

The Clarinetist’s Guide to the Performance of the Clarinet, Viola, and Piano Trios by Mozart, Bruch, and Larsen. D.M.A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Adrienne Marie Marshall, M.M. & M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2013 D.M.A. Document Committee: Caroline Hartig, Advisor, Karen Pierson Daryl Kinney Copyright by Adrienne Marie Marshall 2013 Abstract The purpose of this study is to provide clarinetists with a study guide for the teaching and performance of the clarinet, viola, and piano trios of Mozart, Bruch, and Larsen. A select bibliography of additional compositions for this medium is also provided. Performance practice details, technical suggestions, historical information, and publication details are included for each work. Although there is a sizeable repertoire for this combination of instruments, only a few works have become recognized as standards of the repertoire, including the trios of Mozart and Bruch. A newer addition to this medium is Libby Larsen’s Black Birds, Red Hills, which is likely to become integrated into the standard repertoire. An interview with composer Libby Larsen regarding new music and her compositions is included. It is recommended that complete scores be obtained to accompany this performance guide. The document will conclude with recommendations to further the creation and performance of this medium. ii Dedication This document is dedicated to my family, Christopher Lape, & Dr. Elfie Schults-Berndt. iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor Caroline Hartig, and committee members Karen Pierson and Daryl Kinney for their patience and guidance regarding scholarly research and writing for this document. -

Alexander Goehr Since Brass, Nor Stone

Alexander Goehr Since Brass, nor Stone... Colin Currie percussion • Pavel Haas Quartet The Nash Ensemble Largo Siciliano • ... around Stravinsky www.nmcrec.co.uk/musicmap manere • Clarinet Quintet 1 Since Brass, nor Stone... Op 80 (2008) 13’29 manere Op 81 (2008) 9’16 Fantasy for string quartet and percussion 15 e = 80 ma poco liberamente 0’51 Colin Currie percussion ˆ 16 come sopra 0’56 Pavel Haas Quartet: Veronikaˆ Jaru˚sková violin • Marek Zwiebel violin 17 poco meno, sostenuto 0’54 Pavel Nikl viola • Peter Jaru˚sek cello 18 tempo 1 1’53 19 meno mosso 1’22 …around Stravinsky for violin and wind quartet Op 72 (2002) 11’24 20 in tempo 0’54 2 Prelude, ‘Dushkin’ 3’15 21 andante 0’41 3 Stravinsky: Pastorale 2’41 22 in tempo dell’inizio, ma liberamente 0’53 4 Introduzione and Rondo 5’28 23 in tempo 0’52 David Alberman violin • Gareth Hulse oboe • Richard Hosford clarinet Richard Hosford clarinet Ursula Leveaux bassoon • Richard Watkins horn Marianne Thorsen violin Clarinet Quintet Op 79 (2007) 18’40 24 Largo Siciliano Op 91 (2012) 20’13 5 I Maestoso 1’00 Richard Watkins horn 6 II Poco meno mosso 1’09 Marianne Thorsen violin Ian Brown piano Alexander 7 III Tempo 1 1’38 Goehr 8 IV Tempo 1, poco scherzando 1’13 Total timing 73’45 9 V Tempo 1, poco scherzando 0’54 10 VI Andante 3’34 Since Brass, 11 VII Tempo 1 1’29 nor Stone... The Nash Ensemble 12 VIII Lento 1’24 David Alberman violin • Laura Samuel violin 13 IX Mosso, allegro 2’01 Marianne Thorsen violin • Lawrence Power viola 14 X Saraband 4’18 Paul Watkins cello • Richard Watkins horn Richard Hosford clarinet • David Alberman violin • Laura Samuel violin Richard Hosford clarinet • Gareth Hulse oboe Lawrence Power viola • Paul Watkins cello Ursula Leveaux bassoon • Ian Brown piano Photo: Raoul David Findeisen 2 3 Since Brass, Nor Stone… of the singularly awkward duty categories altogether and start owed by today’s composers to their afresh. -

Press Release Kettle's Yard New Music Series, Programmed by Kate

Press Release Music Nash has performed over 275 new works, including 175 commissions of pieces especially written for the ensemble. At Kettle’s Yard the Nash will perform a new Kettle’s Yard New Music commission by Richard Causton as well as works by Mark-Anthony Turnage, Shostakovich as well as Series, programmed by Stravinsky’s ‘Three pieces for string Quartet’ which was written in 1914 as revolt against the tradition of the Kate Whitley string quartet, inspired by the non-classical rhythms of Russian peasant music. Other established stars of the 2015 new music season include internationally acclaimed mezzo-soprano Lore Lixenberg who, accompanied by January - June 2015 violinist Aisha Orazbeyeva, will perform Gyorgy Kurtág’s extraordinary song cycle, inspired by Kafka’s letters and diaries. Contemporary musicians and composers testing the Concerts by the Nash Ensemble, Shiva Feshareki, boundaries of traditional concert performances include turntables, Aisha Orazbayeva, violin, & Lore Lixenberg, Shiva Feshareki on turntables, Lucy Landymore, solo mezzo-soprano, The Multi-Story Orchestra, Richard percussion, and The Multi-Story Orchestra, who are Uttley, piano, and Lucy Landymore, percussion. based in a disused car park in Peckham. Composer and turntablist Shiva Feshareki has been praised for her Highlights include new commissions by Richard Causton, “virtuoso DJ-ing”, The Times, and will present her works Shiva Feshareki, Kate Whitley & Malgorzata Dzierzon for ensemble and turntables, as well as a new commission and Matthew Kaner. in response to Beauty and Revolution: The Poetry and Art of Ian Hamilton Finlay. Cambridge born Lucy Performances of György Kurtág’s Kafka Fragments, Frank Landymore, winner of the 2010 BBC Young Musician of Zappa’s The Black Page and Gérard Grisey’s Periodes the year Percussion section will perform a recital from Les Espaces Acoustiques.