THE NASH ENSEMBLE of LONDON Amelia Freedman CBE, Artistic Director

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Past Commissions 2014/15

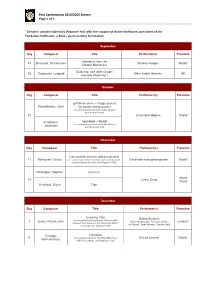

Past Commissions 2014/2015 Season Page 1 of 5 * Denotes commissioned by Wigmore Hall with the support of André Hoffmann, president of the Fondation Hoffmann, a Swiss grant-making foundation September Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Variations from the 14 Birtwistle, Sir Harrison Nicolas Hodges World* Golden Mountains Study No. 44A after Chopin 15 Godowsky, Leopold Marc-André Hamelin UK nouvelle étude No.1 October Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première gefährlich dünn — fragile pieces Petraškevičs, Jānis for double string quartet (co-commissioned by Ensemble Modern and Wigmore Hall) 10 Ensemble Modern World* Schöllhorn, sous-bois – Sextet (co-commissioned by Ensemble Modern Johannes and Wigmore Hall) November Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Carnaval for clarinet, piano and cello 11 Mantovani, Bruno (co-commissioned by Ensemble intercontemporain, Ensemble intercontemporain World* Opéra national de Paris and Wigmore Hall) Montague, Stephen nun-mul World 16 Jenna Sung World Pritchard, Gwyn Tide December Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Uncanny Vale Britten Sinfonia (co-commissioned by Britten Sinfonia with 3 Jones, Patrick John (Emer McDonough, Nicholas Daniel, London* support from donors to the Musically Gifted Joy Farrall, Sarah Burnett, Stephen Bell) campaign and Wigmore Hall) Turnage, Contusion 6 (co-commissioned by The Radcliffe Trust, Belcea Quartet World* Mark-Anthony NMC Recordings and Wigmore Hall) Past Commissions 2014/2015 Season Page 2 of 5 January Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Light and Matter Britten Sinfonia (co-commissioned by Britten Sinfonia with 14 Saariaho, Kaija (Jacqueline Shave, Caroline Dearnley, London* support from donors to the Musically Gifted campaign Huw Watkins) and Wigmore Hall) 3rd Quartet Holt, Simon (co-commissioned by The Radcliffe Trust, World* NMC Recordings, Heidelberger Frühling, and 19 Wigmore Hall) JACK Quartet Haas, Georg Friedrich String Quartet No. -

Historie Der Rheinischen Musikschule Teil 1 Mit Einem Beitrag Von Professor Heinrich Lindlahr

Historie der Rheinischen Musikschule Teil 1 Mit einem Beitrag von Professor Heinrich Lindlahr Zur Geschichte des Musikschulwesens in Köln 1815 - 1925 Zu Beginn des musikfreundlichen 19. Jahrhunderts blieb es in Köln bei hochfliegenden Plänen und deren erfolgreicher Verhinderung. 1815, Köln zählte etwa fünfundzwanzigtausend Seelen, die soeben, wie die Bewohner der Rheinprovinz insgesamt, beim Wiener Kongreß an das Königreich Preußen gefallen waren, 1815 also hatte von Köln aus ein ungenannter Musikenthusiast für die Rheinmetropole eine Ausbildungsstätte nach dem Vorbild des Conservatoire de Paris gefordert. Sein Vorschlag erschien in der von Friedrich Rochlitz herausgegebenen führenden Allgemeinen musikalischen Zeitung zu Leipzig. Doch Aufrufe solcher Art verloren sich hierorts, obschon Ansätze zu einem brauchbaren Musikschulgebilde in Köln bereits bestanden hatten: einmal in Gestalt eines Konservatorienplanes, wie ihn der neue Maire der vormaligen Reichstadt, Herr von VVittgenstein, aus eingezogenen kirchlichen Stiftungen in Vorschlag gebracht hatte, vorwiegend aus Restklassen von Sing- und Kapellschulen an St. Gereon, an St. Aposteln, bei den Ursulinen und anderswo mehr, zum anderen in Gestalt von Heimkursen und Familienkonzerten, wie sie der seit dem Einzug der Franzosen, 1794, stellenlos gewordene Salzmüdder und Domkapellmeister Dr. jur. Bernhard Joseph Mäurer führte. Unklar blieb indessen, ob sich der Zusammenschluss zu einem Gesamtprojekt nach den Vorstellungen Dr. Mäurers oder des Herrn von Wittgenstein oder auch jenes Anonymus deshalb zerschlug, weil die Durchführung von Domkonzerten an Sonn- und Feiertagen kirchenfremden und besatzungsfreundlichen Lehrkräften hätte zufallen sollen, oder mehr noch deshalb, weil es nach wie vor ein nicht überschaubares Hindernisrennen rivalisierender Musikparteien gab, deren manche nach Privatabsichten berechnet werden müssten, wie es die Leipziger Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung von 1815 lakonisch zu kommentieren wusste. -

London Mozart Players Wind Trio When He Left to Focus on His Freelance Career

Timothy Lines (Clarinet) Timothy studied at the Royal College of Music with Michael Collins and now enjoys a wide- ranging career as a clarinettist. He has played with all the major symphony orchestras in London as well as with chamber groups including London Sinfonietta and the Nash Ensemble. From 1999 to 2003 he was Principal Clarinet of the London Symphony Orchestra and was also chairman of the orchestra during his last year there. From September 2004 to January 2006 he was section leader clarinet of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, London Mozart Players Wind Trio when he left to focus on his freelance career. He plays on original instruments with the English Baroque Soloists, the Orchestre Revolutionnaire et Romantique and the Orchestra of Thursday 12th March 2020 at 7.30 pm the Age of Enlightenment and is also frequently engaged to record film music and pop music Cavendish Hall, Edensor tracks. Timothy is Professor of Clarinet at both the Royal College of Music and the Royal Academy of Music, and is the clarinet coach for the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain. In March 2016 he was awarded a Fellowship of the Royal College of Music and was later that year invited to become Principal Clarinet of the London Mozart Players. Concert Champêtre H. TOMASI Gareth Hulse (Oboe) (1901-1971) After reading music at Cambridge, Gareth Hulse studied with Janet Craxton at the Royal Divertimento K439b W.A. MOZART Academy of Music, and with Heinz Holliger at the Freiburg Hochschule fur Musik. On his (1756-1791) return to England he was appointed Principal Oboe with the Northern Sinfonia, a position he has since held with English National Opera and the London Philharmonic. -

November 2016

November 2016 Igor Levit INSIDE: Borodin Quartet Le Concert d’Astrée & Emmanuelle Haïm Imogen Cooper Iestyn Davies & Thomas Dunford Emerson String Quartet Ensemble Modern Brigitte Fassbaender Masterclasses Kalichstein/Laredo/ Robinson Trio Dorothea Röschmann Sir András Schiff and many more Box Office 020 7935 2141 Online Booking www.wigmore-hall.org.uk How to Book Wigmore Hall Box Office 36 Wigmore Street, London W1U 2BP In Person 7 days a week: 10 am – 8.30 pm. Days without an evening concert 10 am – 5 pm. No advance booking in the half hour prior to a concert. By Telephone: 020 7935 2141 7 days a week: 10 am – 7 pm. Days without an evening concert 10 am – 5 pm. There is a non-refundable £3.00 administration fee for each transaction, which includes the return of your tickets by post if time permits. Online: www.wigmore-hall.org.uk 7 days a week; 24 hours a day. There is a non-refundable £2.00 administration charge. Standby Tickets Standby tickets for students, senior citizens and the unemployed are available from one hour before the performance (subject to availability) with best available seats sold at the lowest price. NB standby tickets are not available for Lunchtime and Coffee Concerts. Group Discounts Discounts of 10% are available for groups of 12 or more, subject to availability. Latecomers Latecomers will only be admitted during a suitable pause in the performance. Facilities for Disabled People full details available from 020 7935 2141 or [email protected] Wigmore Hall has been awarded the Bronze Charter Mark from Attitude is Everything TICKETS Unless otherwise stated, tickets are A–D divided into five prices ranges: BALCONY Stalls C – M W–X Highest price T–V Stalls A – B, N – P Q–S 2nd highest price Balcony A – D N–P 2nd highest price STALLS Stalls BB, CC, Q – S C–M 3rd highest price A–B Stalls AA, T – V CC CC 4th highest price BB BB PLATFORM Stalls W – X AAAA AAAA Lowest price This brochure is available in alternative formats. -

Artist Series: Ani Kavafian Program

The following program notes may only be used in conjunction with the one-time streaming term for the corresponding Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center (CMS) Front Row National program, with the following credit(s): Program notes by Laura Keller, CMS Editorial Manager © 2021 Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center Any other use of these materials in connection with non-CMS concerts or events is prohibited. ARTIST SERIES: ANI KAVAFIAN PROGRAM Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Scherzo, WoO 2, from “F-A-E” Sonata for Violin and Piano (1853) Ani Kavafian, violin • Alessio Bax, piano Arno Babadjanian (1921-1983) “Andante” from Trio in F-sharp minor for Piano, Violin, and Cello (1952) Gloria Chien, piano • Ani Kavafian, violin • Mihai Marica, cello INTERMISSION (Q&A with the artist) Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904) Trio in F minor for Piano, Violin, and Cello, Op. 65 (1883) Allegro ma non troppo Allegretto grazioso Poco adagio Finale: Allegro con brio Orion Weiss, piano • Ani Kavafian, violin • Carter Brey, cello NOTES ON THE PROGRAM Scherzo, WoO 2, from “F-A-E” Sonata for Violin and Piano (1853) Johannes Brahms (Hamburg, 1833 – Vienna, 1897) The F-A-E Sonata was an unusual joint composition project at the behest of Robert Schumann. The violinist Joseph Joachim came to visit him in Düsseldorf in October 1853, and Schumann rallied two of his young students, Brahms and Albert Dietrich, to compose a violin sonata with him. Brahms had only met Schumann the previous month, arriving with an introduction from Joachim, but Schumann was Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center immediately taken with Brahms and the two had become fast friends. -

Unknown Brahms.’ We Hear None of His Celebrated Overtures, Concertos Or Symphonies

PROGRAM NOTES November 19 and 20, 2016 This weekend’s program might well be called ‘Unknown Brahms.’ We hear none of his celebrated overtures, concertos or symphonies. With the exception of the opening work, all the pieces are rarities on concert programs. Spanning Brahms’s youth through his early maturity, the music the Wichita Symphony performs this weekend broadens our knowledge and appreciation of this German Romantic genius. Hungarian Dance No. 6 Johannes Brahms Born in Hamburg, Germany May 7, 1833 in Hamburg, Germany Died April 3, 1897 in Vienna, Austria Last performed March 28/29, 1992 We don’t think of Brahms as a composer of pure entertainment music. He had as much gravitas as any 19th-century master and is widely regarded as a great champion of absolute music, music in its purest, most abstract form. Yet Brahms loved to quaff a stein or two of beer with friends and, within his circle, was treasured for his droll sense of humor. His Hungarian Dances are perhaps the finest examples of this side of his character: music for relaxation and diversion, intended to give pleasure to both performer and listener. Their music is familiar and beloved - better known to the general public than many of Brahms’s concert works. Thus it comes as a surprise to many listeners to learn that Brahms specifically denied authorship of their melodies. He looked upon these dances as arrangements, yet his own personality is so evident in them that they beg for consideration as original compositions. But if we deem them to be authentic Brahms, do we categorize them as music for one-piano four-hands, solo piano, or orchestra? Versions for all three exist in Brahms's hand. -

Download Booklet

C M Y B The Nash Ensemble Sally Matthews C M C M Y B www.onyxclassics.com ONYX 4005 Y B TURNAGE THIS SILENCE p1 Eulogy p12 Two Baudelaire Songs Cantilena Slide Stride PAGE XX12 PAGE 01 C M Y B C M Y B MARK-ANTHONY TURNAGE (1960-) Chamber Works This Silence for Octet (1992-3) 1 Dance 8.21 2 Dirge 7.14 True Life Stories for solo piano (1995-9) 3 Elegy for Andy 3.28 4 William’s Pavane 1.37 5 Song for Sally 2.35 6 Edward’s refrain 3.12 7 Tune for Toru 2.04 C M C M Y B 8 Slide Stride for piano and string quartet (2002) 13.02 Y B Two Baudelaire Songs for soprano and seven instruments (2004) p11 9 Harmonie du Soir 5.51 10 L’invitation au voyage 4.32 p2 11 Eulogy for viola and eight instruments (2003) 9.56 Two Vocalises for cello and piano (2002) Executive Producer: Chris Craker 12 Maclaren’s farewell 3.08 Producer & Engineer: Chris Craker 13 Vocalise 2.32 Post-Production: Simon Haram Mastered by: Chris Craker and Simon Haram 14 Cantilena for oboe and string quartet (2001) 10.45 Recording Location: Henry Wood Hall, London, 24-26 October 2004 Publishers: Schott Musik International [1-8], [12-14], Boosey & Hawkes Ltd [9-11] Total Time 78.34 Product Director: Paul Moseley Cover photograph © Hanya Chlala/Arena PAL Design: CEH PAGE 02 PAGE 11 C M Y B C M Y B L’invitation au voyage Invitation to the voyage Mon enfant, ma soeur, My child, my sister, Songe à la douceur Think of the rapture D'aller là-bas vivre ensemble! Of living together there! Aimer à loisir, Of loving at will, Aimer et mourir Of loving till death, Au pays qui te ressemble! In the land that is like you! Les soleils mouillés The misty sunlight De ces ciels brouillés Of those cloudy skies Pour mon esprit ont les charmes Has for my spirit the charms, Si mystérieux So mysterious, De tes traîtres yeux, Of your treacherous eyes, Brillant à travers leurs larmes. -

The Perfect Pitch 2012

2012 2011–2012 Javier Alvarez, Composer Samuel Ramey, Bass-Baritone Peter Bagley, Conductor Sandra Rivers, Piano Jay Batzner, Composer Gail Robertson, Euphonium Shawn Bell Quartet Christine Salerno and ZIJI Fred Hersch, Piano and Composer Justin Benavidez, Tuba Mauricio Salguero, Clarinet Janet Hilton, Clarinet Gene Bertoncini, Guitar John Sampen, Saxophone Edith Hines, Baroque Violin Alex Brown, Piano San Francisco Jazz Collective Jon Holden, Clarinet Mark Bunce, Composer and Engineer Nina Schumann and Lúis Magalháes, Piano Pat Hughes, Horn Roger Chase, Viola Dan Scott, String Education Specialist Naoko Imafuku, Piano Larry Clark, Conductor Kendrick Scott, Drums JaLaLa Evan Conroy, Bass Trombone Mira Shifrin, Flute Lia Jensen-Abbott, Piano Mike Crotty, Multi-instrumentalist Alan Siebert, Trumpet Mayumi Kanagawa, Violin Vocal Coach and Piano Composer Vera Danchenko-Stern, (Stulberg Silver Medalist) Mark Snyder, Joel Davel, Percussion Jack Stamp, Conductor and Composer Christopher Kantner, Flute The Quincy Davis Project Elizabeth Start, Cello Kontras String Quartet Alissa Deeter, Soprano John Chappell Stowe, Organ and Harpsichord Massimo LaRosa, Trombone Detroit Symphony Orchestra Brass Players Mihai Tetel, Cello Dan Levitin, Neuroscientist Piano Piano Ron DiSalvio, and Cognitive Psychologist Yu-Lien The, Paquito D’Rivera, Clarinet, Saxophone, Walter Thompson, Soundpainter and Composer The Dave Liebman Group and Composer Trollstilt Andrew List, Composer John Duykers, Tenor Dan Trueman, Composer Paul Loesel, Piano and Composer Euclid Quartet -

Bemerkungen.Fm Seite 25 Freitag, 19

HN 917_Bemerkungen.fm Seite 25 Freitag, 19. März 2010 10:59 10 25 Bemerkungen vorlage muss als verschollen gelten. T 65 f. In T 73 in A bei Klav o zu- Hauptquelle der vorliegenden Ausgabe sätzlich v es1 auf Zwei. ist E. Dabei sind Partitur und die der 87 Klav o: 1. Akkord nach A, in E mit Ausgabe beigegebenen Einzelstimmen f 2 statt d 2, in der von Clara Schu- Klar = Klarinette; Klav o = Klavier als gleichberechtigte Quellen anzusehen. mann zwischen 1879 und 1893 oberes System; Klav u = Klavier unteres Sie stimmen nicht immer miteinander herausgegebenen Gesamtausgabe System; Va = Viola; T = Takt(e) überein. Möglicherweise wurden die Robert Schumann’s Werke (Serie V, Stimmen nicht nach der Vorlage einer Nr. 26, 1881) korrigiert. handschriftlichen Partitur, sondern 88 Klav o: 2. Akkord in A es/es1 statt nach handschriftlichen Stimmen gesto- g/g 1; Versehen oder nachträgliche chen, die vorher bei Aufführungen be- Korrektur? Quellen nutzt worden waren. 91 Va: Bogen nach A und ES; in E erst A Autograph. Paris, Bibliothèque Zeichen, die in beiden Quellen fehlen, ab 2. Note. nationale de France, Signatur aus musikalischen Gründen aber not- 93 f. Va: Bogen in A jeweils bereits ab Ms. 337. 4 Blätter und ein Bei- wendig scheinen, sind in runden Klam- Eins; hier aber ES und E überein- lageblatt, kein Titelblatt. Über- mern ergänzt. stimmend erst ab 2. Note. schrift auf S. 1: Märchenerzäh- 148 Klav u: In E fehlt h vor h, vgl. Par- lungen. Rechts: Albert Dietrich allelstelle T 52. gewidmet. Am Ende von Nr. I Einzelbemerkungen I Lebhaft, nicht zu schnell Datierung: d. -

2016/17 Season Preview and Appeal

2016/17 SEASON PREVIEW AND APPEAL The Wigmore Hall Trust would like to acknowledge and thank the following individuals and organisations for their generous support throughout the THANK YOU 2015/16 Season. HONORARY PATRONS David and Frances Waters* Kate Dugdale A bequest from the late John Lunn Aubrey Adams David Evan Williams In memory of Robert Easton David Lyons* André and Rosalie Hoffmann Douglas and Janette Eden Sir Jack Lyons Charitable Trust Simon Majaro MBE and Pamela Majaro MBE Sir Ralph Kohn FRS and Lady Kohn CORPORATE SUPPORTERS Mr Martin R Edwards Mr and Mrs Paul Morgan Capital Group The Eldering/Goecke Family Mayfield Valley Arts Trust Annette Ellis* Michael and Lynne McGowan* (corporate matched giving) L SEASON PATRONS Clifford Chance LLP The Elton Family George Meyer Dr C A Endersby and Prof D Cowan Alison and Antony Milford L Aubrey Adams* Complete Coffee Ltd L American Friends of Wigmore Hall Duncan Lawrie Private Banking The Ernest Cook Trust Milton Damerel Trust Art Mentor Foundation Lucerne‡ Martin Randall Travel Ltd Caroline Erskine The Monument Trust Karl Otto Bonnier* Rosenblatt Solicitors Felicity Fairbairn L Amyas and Louise Morse* Henry and Suzanne Davis Rothschild Mrs Susan Feakin Mr and Mrs M J Munz-Jones Peter and Sonia Field L A C and F A Myer Dunard Fund† L The Hargreaves and Ball Trust BACK OF HOUSE Deborah Finkler and Allan Murray-Jones Valerie O’Connor Pauline and Ian Howat REFURBISHMENT SUMMER 2015 Neil and Deborah Franks* The Nicholas Boas Charitable Trust The Monument Trust Arts Council England John and Amy Ford P Parkinson Valerie O’Connor The Foyle Foundation S E Franklin Charitable Trust No. -

KORBINIAN ALTENBERGER, Violin IGNAT SOLZHENITSYN, Piano Sunday, April 7 – 3:00 PM Rhoden Arts Center, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts

PREVIEW NOTES KORBINIAN ALTENBERGER, violin IGNAT SOLZHENITSYN, piano Sunday, April 7 – 3:00 PM Rhoden Arts Center, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts PROGRAM Scherzo in C Minor from F-A-E Sonata Johannes Brahms Violin Sonata in G Major, Op. 78 Composed: 1853 Johannes Brahms Duration: 5 minutes Born: May 7, 1833, in Hamburg, Germany Died: April 3, 1897, in Vienna, Austria This Scherzo was written as part of the F-A-E Sonata--a Composed: 1878-79 collaborative work between Brahms, Robert Schumann, and Duration: 28 minutes Albert Dietrich--and it marks the height of Brahms' involvement with Robert Schumann's musical circle. The F-A- Composed in the high summer of his creative career after the E, incidentally, stands for frei aber einsam (free but alone), completion of the Symphony No. 1 and the Violin Concerto, the group's motto. By far the best movement of the Sonata Brahms's Violin Sonata in G Major is a gloriously lyrical work (Schumann wrote the second and fourth movements, and with long-breathed melodies rather than terse themes, and Dietrich the first), Brahms's contribution is rhythmically expansive extrapolations rather than concise developments. exciting and original in conception, and it is still part of the It is also one of Brahms's most tightly structured and violin repertoire. cogently argued works, with a degree of formal integration rare in his works. Violin Sonata in D Minor, Op. 108 Johannes Brahms Violin Sonata in A Major, Op. 100 Composed: 1886-88 Johannes Brahms Duration: 22 minutes Composed: 1886 Duration: 20 minutes Brahms began his Sonata for piano and violin in D Minor, Op. -

2018/19 Season

MARCH 2018/19 Season wigmore-hall.org.uk 2 • SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER wigmore-hall.org.uk How to Book Wigmore Hall Box Office TICKETS 36 Wigmore Street, London W1U 2BP Unless otherwise stated, tickets are divided into five price ranges: In Person ■ Stalls C – M Highest price 7 days a week: 10.00am - 8.30pm. ■ Stalls A – B, N – P 2nd highest price Days without an evening concert: ■ Balcony A – D 2nd highest price 10.00am - 5.00pm. No advance booking in the ■ Stalls BB, CC, Q – S 3rd highest price half hour prior to a concert. ■ Stalls AA, T – V 4th highest price ■ Stalls W – X Lowest price By Telephone: 020 7935 2141 7 days a week: 10.00am - 7.00pm. AA AA Days without an evening concert: AA STAGE AA AA AA 10.00am - 5.00pm. BB BB There is a non-refundable £4.00 administration CC CC A A charge for each transaction. B B C C D D Online: wigmore-hall.org.uk E E F FRONT FRONT F STALLS STALLS 7 days a week; 24 hours a day. There is a G G non-refundable £3.00 administration charge. H H I I J J K K Standby Tickets L L M M Standby tickets for students, senior citizens and N N the unemployed are available from one hour O O P P before the performance (subject to availability) Q Q with best available seats sold at the lowest price. R R S S REAR REAR NB standby tickets are not available for T STALLS STALLS T U U Lunchtime and Sunday Morning Concerts.