The Clarinetist's Guide to the Performance of the Clarinet, Viola

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MSM WIND ENSEMBLE Eugene Migliaro Corporon, Conductor Joseph Mohan (DMA ’21), Piano

MSM WIND ENSEMBLE Eugene Migliaro Corporon, Conductor Joseph Mohan (DMA ’21), piano FRIDAY, JANUARY 18, 2019 | 7:30 PM NEIDORFF-KARPATI HALL FRIDAY, JANUARY 18, 2019 | 7:30 PM NEIDORFF-KARPATI HALL MSM WIND ENSEMBLE Eugene Migliaro Corporon, Conductor Joseph Mohan (DMA ’21), piano PROGRAM JOHN WILLIAMS For New York (b. 1932) (Trans. for band by Paul Lavender) FRANK TICHELI Acadiana (b. 1958) At the Dancehall Meditations on a Cajun Ballad To Lafayette IGOR ST R AVINSKY Concerto for Piano and Wind Instruments (1882–1971) Lento; Allegro Largo Allegro Joseph Mohan (DMA ’21), piano Intermission VITTORIO Symphony No. 3 for Band GIANNINI Allegro energico (1903–1966) Adagio Allegretto Allegro con brio CENTENNIAL NOTE Vittorio Giannini (1903–1966) was an Italian-American composer calls upon the band’s martial associations, with an who joined the Manhattan School of Music faculty in 1944, where he exuberant march somewhat reminiscent of similar taught theory and composition until 1965. Among his students were efforts by Sir William Walton. Along with the sunny John Corigliano, Nicolas Flagello, Ludmila Ulehla, Adolphus Hailstork, disposition and apparent straightforwardness of works Ursula Mamlok, Fredrick Kaufman, David Amram, and John Lewis. like the Second and Third Symphonies, the immediacy MSM founder Janet Daniels Schenck wrote in her memoir, Adventure and durability of their appeal is the result of considerable in Music (1960), that Giannini’s “great ability both as a composer and as subtlety in motivic and harmonic relationships and even a teacher cannot be overestimated. In addition to this, his remarkable in voice leading. personality has made him beloved by all.” In addition to his Symphony No. -

Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 As a Contribution to the Violist's

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory Rafal Zyskowski Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Zyskowski, Rafal, "A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3366. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3366 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A TALE OF LOVERS: CHOPIN’S NOCTURNE OP. 27, NO. 2 AS A CONTRIBUTION TO THE VIOLIST’S REPERTORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Rafal Zyskowski B.M., Louisiana State University, 2008 M.M., Indiana University, 2010 May 2014 ©2014 Rafal Zyskowski All rights reserved ii Dedicated to Ms. Dorothy Harman, my best friend ever iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As always in life, the final outcome of our work results from a contribution that was made in one way or another by a great number of people. Thus, I want to express my gratitude to at least some of them. -

Vorwort Der Ihm Eigenen Selbstironie – Das Ma Folgenden Johannes Brahms

Vorwort der ihm eigenen Selbstironie – das Ma Folgenden Johannes Brahms. Briefwech- nuskript des ganzen Werks als „Probe“ sel, Bd. XII, hrsg. von Max Kalbeck, Ber bezeichnete und es komplett an Mandy lin 1919, Reprint Tutzing 1974, S. 47 ff.). czewski schickte. Dieser begann mit der Nach der Berliner Uraufführung über Zwar hatte Johannes Brahms (1833 – 97) Partiturabschrift des Quintetts, vermut sandte er ihm am 24. Dezember 1891 im Dezember 1890 seinem Verleger Fritz lich weil Brahms’ damaliger Hauptko zunächst die Partiturabschrift des Quin Simrock angekündigt, mit dem Kompo pist William Kupfer zu dieser Zeit noch tetts als Vorlage für ein geplantes Ar nieren aufhören zu wollen, aber schon mit der Abschrift des Klarinettentrios rangement für Klavier zu vier Händen. bald sollte er nochmals tätig werden. Ein befasst war. Nach Abschluss von Satz I Kurz nach der zweiten Aufführung des wichtiger Impuls dafür ging von dem durch Mandyczewski setzte Kupfer die Klarinettenquintetts in Wien gingen am Klarinettisten der Meininger Hofkapelle Abschrift fort und kopierte die Stim 23. Januar dann auch die abschriftlichen Richard Mühlfeld aus, den Brahms im men, vermutlich schrieb er auch die al Stimmen an Simrock zur Vorbereitung Frühjahr 1891 näher kennen und sehr ternative Solopartie für Viola aus. Wann des Stichs. Vermutlich im Februar 1892 schätzen lernte. Begeistert schwärmte die abschriftlichen Materialien fertigge las der Komponist Druckfahnen von er am 17. März in einem Brief an Clara stellt waren, kann nicht genau festge Partitur und Stimmen Korrektur, denn Schumann, man könne „nicht schöner stellt werden. Spätestens zu den ersten am 25. Februar beklagte er sich brief Klarinette blasen, als es der hiesige Herr Proben der beiden neuen Stücke mit Ri lich darüber, dass die Stimmen bereits Mühlfeld tut“. -

Past Commissions 2014/15

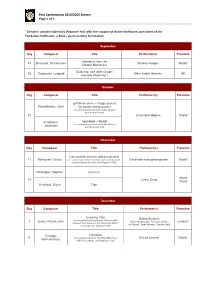

Past Commissions 2014/2015 Season Page 1 of 5 * Denotes commissioned by Wigmore Hall with the support of André Hoffmann, president of the Fondation Hoffmann, a Swiss grant-making foundation September Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Variations from the 14 Birtwistle, Sir Harrison Nicolas Hodges World* Golden Mountains Study No. 44A after Chopin 15 Godowsky, Leopold Marc-André Hamelin UK nouvelle étude No.1 October Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première gefährlich dünn — fragile pieces Petraškevičs, Jānis for double string quartet (co-commissioned by Ensemble Modern and Wigmore Hall) 10 Ensemble Modern World* Schöllhorn, sous-bois – Sextet (co-commissioned by Ensemble Modern Johannes and Wigmore Hall) November Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Carnaval for clarinet, piano and cello 11 Mantovani, Bruno (co-commissioned by Ensemble intercontemporain, Ensemble intercontemporain World* Opéra national de Paris and Wigmore Hall) Montague, Stephen nun-mul World 16 Jenna Sung World Pritchard, Gwyn Tide December Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Uncanny Vale Britten Sinfonia (co-commissioned by Britten Sinfonia with 3 Jones, Patrick John (Emer McDonough, Nicholas Daniel, London* support from donors to the Musically Gifted Joy Farrall, Sarah Burnett, Stephen Bell) campaign and Wigmore Hall) Turnage, Contusion 6 (co-commissioned by The Radcliffe Trust, Belcea Quartet World* Mark-Anthony NMC Recordings and Wigmore Hall) Past Commissions 2014/2015 Season Page 2 of 5 January Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Light and Matter Britten Sinfonia (co-commissioned by Britten Sinfonia with 14 Saariaho, Kaija (Jacqueline Shave, Caroline Dearnley, London* support from donors to the Musically Gifted campaign Huw Watkins) and Wigmore Hall) 3rd Quartet Holt, Simon (co-commissioned by The Radcliffe Trust, World* NMC Recordings, Heidelberger Frühling, and 19 Wigmore Hall) JACK Quartet Haas, Georg Friedrich String Quartet No. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

A Brief History of the Sonata with an Analysis and Comparison of a Brahms’ and Hindemith’S Clarinet Sonata

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses 1968 A Brief History of the Sonata with an Analysis and Comparison of a Brahms’ and Hindemith’s Clarinet Sonata Kenneth T. Aoki Central Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Composition Commons, and the Education Commons Recommended Citation Aoki, Kenneth T., "A Brief History of the Sonata with an Analysis and Comparison of a Brahms’ and Hindemith’s Clarinet Sonata" (1968). All Master's Theses. 1077. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/1077 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE SONATA WITH AN ANALYSIS AND COMPARISON OF A BRAHMS' AND HINDEMITH'S CLARINET SONATA A Covering Paper Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Music Central Washington State College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Education by Kenneth T. Aoki August, 1968 :N01!83 i iuJ :JV133dS q g re. 'H/ £"Ille; arr THE DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC CENTRAL WASHINGTON STATE COLLEGE presents in KENNETH T. AOKI, Clarinet MRS. PATRICIA SMITH, Accompanist PROGRAM Sonata for Clarinet and Piano in B flat Major, Op. 120 No. 2. J. Brahms Allegro amabile Allegro appassionato Andante con moto II Sonatina for Clarinet and Piano .............................................. 8. Heiden Con moto Andante Vivace, ma non troppo Caprice for B flat Clarinet ................................................... -

London Mozart Players Wind Trio When He Left to Focus on His Freelance Career

Timothy Lines (Clarinet) Timothy studied at the Royal College of Music with Michael Collins and now enjoys a wide- ranging career as a clarinettist. He has played with all the major symphony orchestras in London as well as with chamber groups including London Sinfonietta and the Nash Ensemble. From 1999 to 2003 he was Principal Clarinet of the London Symphony Orchestra and was also chairman of the orchestra during his last year there. From September 2004 to January 2006 he was section leader clarinet of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, London Mozart Players Wind Trio when he left to focus on his freelance career. He plays on original instruments with the English Baroque Soloists, the Orchestre Revolutionnaire et Romantique and the Orchestra of Thursday 12th March 2020 at 7.30 pm the Age of Enlightenment and is also frequently engaged to record film music and pop music Cavendish Hall, Edensor tracks. Timothy is Professor of Clarinet at both the Royal College of Music and the Royal Academy of Music, and is the clarinet coach for the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain. In March 2016 he was awarded a Fellowship of the Royal College of Music and was later that year invited to become Principal Clarinet of the London Mozart Players. Concert Champêtre H. TOMASI Gareth Hulse (Oboe) (1901-1971) After reading music at Cambridge, Gareth Hulse studied with Janet Craxton at the Royal Divertimento K439b W.A. MOZART Academy of Music, and with Heinz Holliger at the Freiburg Hochschule fur Musik. On his (1756-1791) return to England he was appointed Principal Oboe with the Northern Sinfonia, a position he has since held with English National Opera and the London Philharmonic. -

March 2021 Program Ponderings

Program Ponderings March Director of Programs - Brad Ray 2021 Well, top of the mornin’ to ya! It’s free to play, and like the posters For those of you, like myself, who say, “It Pays to Play!!” have a “wee bit of Irish” in them, you will be Dublin’ over with Did you know that Village laughter at this terrible St. Pat- Shores is the first senior living com- rick’s Day pun. But alas, perhaps munity that Summit Music began we should focus on the luck we playing on a regular basis? Well, are all experiencing, being that a now these intrepid troops bring their vast majority of the staff and resi- amazing music to parking lots all dents at Village Shores have had over the metro! We are blessed to BOTH vaccination shots! That have them scheduled for two con- puts us way ahead of the curve! certs in March, so make sure to mark However, as we enter March, we your calendar! are continuing with the safety pro- The Scenic Drives with Victor tocols already firmly in place: on Thursdays will continue, with us Now, more than ever, we must looking at adding more as the weath- remain diligent in our fight to pre- er warms up. We will still be limiting vent the spread of COVID-19, es- the number of riders, as social dis- pecially since it seems like the end tancing protocols remain in place. of the tunnel is in view! So let’s The medical runs on Tuesday will al- take a look at some of the things so stay the same. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

The Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano (1988) by David Maslanka

THE SONATA FOR ALTO SAXOPHONE AND PIANO (1988) BY DAVID MASLANKA: AN ANALYTIC AND PERFORMANCE GUIDE. by CAMILLE LOUISE OLIN (Under the Direction of Kenneth Fischer) ABSTRACT In recent years, the Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano by David Maslanka has come to the forefront of saxophone literature, with many university professors and graduate students aspiring to perform this extremely demanding work. His writing encompasses a range of traditional and modern elements. The traditional elements involved include the use of “classical” forms, a simple harmonic language, and the lyrical, vocal qualities of the saxophone. The contemporary elements include the use of extended techniques such as multiphonics, slap tongue, manipulation of pitch, extreme dynamic ranges, and the multitude of notes in the altissimo range. Therefore, a theoretical understanding of the musical roots of this composition, as well as a practical guide to approaching the performance techniques utilized, will be a valuable aid and resource for saxophonists wishing to approach this composition. INDEX WORDS: David Maslanka, saxophone, performer’s guide, extended techniques, altissimo fingerings. THE SONATA FOR ALTO SAXOPHONE AND PIANO (1988) BY DAVID MASLANKA: AN ANALYTIC AND PERFORMANCE GUIDE. by CAMILLE OLIN B. Mus. Perf., Queensland Conservatorium Griffith University, Australia, 2000 M.M., The University of Georgia, 2003 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2006 © 2007 Camille Olin All Rights Reserved THE SONATA FOR ALTO SAXOPHONE AND PIANO (1988) BY DAVID MASLANKA: AN ANALYTIC AND PERFORMANCE GUIDE. by CAMILLE OLIN Major ProfEssor: KEnnEth FischEr CommittEE: Adrian Childs AngEla JonEs-REus D. -

Vahdah Olcott-Bickford Collection, 1800-2008

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8zp4c79 No online items Guide to the Vahdah Olcott-Bickford Collection, 1800-2008 Special Collections & Archives Oviatt Library California State University, Northridge 18111 Nordhoff St. Northridge, CA, 91330 URL: http://library.csun.edu/SCA Email: [email protected] Phone: (818) 677-2832 Fax: (818) 677-2589 © Copyright 2012 Special Collections & Archives. All rights reserved. Guide to the Vahdah IGRA/VOB 1 Olcott-Bickford Collection, 1800-2008 Overview of the Collection Collection Title: Vahdah Olcott-Bickford Collection Dates: 1800-2008 Bulk Dates: 1923-1979 Identification: IGRA/VOB Creator: Olcott-Bickford, Vahdah, 1885-1980 Physical Description: 88.71 linear feet Language of Materials: English French German Spanish; Castilian Italian Portuguese Repository: International Guitar Research Archives (IGRA) Abstract: Vahdah Olcott-Bickford, née Ethel Lucretia Olcott, was an professional teacher of the Guitar, most well known for her influential Guitar Method, Op. 25, and the Advanced Course, Op. 116. She also wrote numerous articles about the guitar, and corresponded with other musicians and enthusiasts about the instrument throughout her long career. The Vahdah Olcott-Bickford Collection documents Olcott-Bickford’s professional life as a classical guitarist, an avid member of various organizations in the United States, her work with guitarists around the world, and her personal life. The collection includes scores, letters, photographs, newspaper clippings, receipts, articles, lecture notes, and guest books, and dates from 1874-1980. Biographical Information: Ethel Lucretia Olcott was born on October 17, 1885 in Norwalk, Ohio. She was three years old when she and her parents moved to Los Angeles, California. At the age of eight she started guitar lessons with George Lindsay, a well-known classic guitarist. -

Slap Tongue (Saxophone Pizzicato)

Excerpt from “Part IV: Extended Techniques for Saxophone” Writing for Saxophones: A Guide to the Tonal Palette of the Saxophone Family for Composers, Arrangers and Performers by Jay C. Easton, D.M.A. (for further excerpts and ordering information, please visit http://baxtermusicpublishing.com) • Slap Tongue (saxophone pizzicato) Slap tongue is a versatile and interesting effect that is available in four varieties: 1. “melodic” slap or pizzicato (clearly pitched): melodic “plucking” sound entire keyed range of horn (but not altissimo) Maximum tempo: 240 beats per minute Possible from p to f dynamics 2. “slap tone” (clearly pitched): melodic slap attack followed by normal tone Maximum tempo: 200 beats per minute Possible from p to f dynamics 3. “woodblock” slap (unpitched): soft, dry percussive sound Maximum tempo: 200 beats per minute Possible from p to mf dynamics 4. “explosive” slap or “open” slap (unpitched): loud percussive sound Maximum tempo: 70 beats per minute Possible from mf to ff dynamics Not all saxophonists know how to slap tongue but an increasing number are learning the technique. The “melodic” slap and “slap tone” are produced by holding the tongue against about 1/3 to 1/2 of the tip end of the reed surface – a centimeter or so – and creating a suction-cup effect between tongue and reed. This is accomplished by pulling the middle of the tongue slightly away from the reed while keeping the edges and tip of the tongue sealed tight against it. The tongue is then quickly released by pushing it forward and downward away from the reed, creating suction between the tongue and the reed; this tongue motion is accompanied by sudden slight impulse of air.