KOBE ECONOMIC & BUSINESS REVIEW No.5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copper in the Early Modern Sino-Japanese Trade Monies, Markets, and Finance in East Asia, 1600–1900

Copper in the Early Modern Sino-Japanese Trade Monies, Markets, and Finance in East Asia, 1600–1900 Edited by Hans Ulrich Vogel VOLUME 7 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/mmf Copper in the Early Modern Sino-Japanese Trade Edited by Keiko Nagase-Reimer LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: From “Scroll with views of the Dutch Factory and Chinese Quarter in Nagasaki 唐館図 蘭館図絵巻” drawn by Ishizaki Yūshi 石崎融思. Courtesy of Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture 長崎歴史文化博物館. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Nagase-Reimer, Keiko. Title: Copper in the early modern Sino-Japanese trade / edited by Keiko Nagase-Reimer. Description: Leiden : Brill, 2016. | Series: Monies, markets, and finance in East Asia, 1600-1900, ISSN 2210-2876 ; volume 7 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2015029107| ISBN 9789004299450 (hardback : acid-free paper) | ISBN 9789004304512 (e-book) Subjects: LCSH: Copper industry and trade—Japan—History. | Copper industry and trade—China—History. | Japan—Commerce—China—History. | China--Commerce—Japan—History. | Japan—Economic conditions—1600–1868. Classification: LCC HD9539.C7 J323 2016 | DDC 382/.4566930952—dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015029107 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, ipa, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 2210-2876 isbn 978-90-04-29945-0 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-30451-2 (e-book) Copyright 2016 by Koninklijke Brill nv, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill nv incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Hes & De Graaf, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Rodopi and Hotei Publishing. -

Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2014 Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan Laura Nuffer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Nuffer, Laura, "Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan" (2014). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1389. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1389 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1389 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan Abstract Interspecies marriage (irui kon'in) has long been a central theme in Japanese literature and folklore. Frequently dismissed as fairytales, stories of interspecies marriage illuminate contemporaneous conceptions of the animal-human boundary and the anxieties surrounding it. This dissertation contributes to the emerging field of animal studies yb examining otogizoshi (Muromachi/early Edo illustrated narrative fiction) concerning elationshipsr between human women and male mice. The earliest of these is Nezumi no soshi ("The Tale of the Mouse"), a fifteenth century ko-e ("small scroll") attributed to court painter Tosa Mitsunobu. Nezumi no soshi was followed roughly a century later by a group of tales collectively named after their protagonist, the mouse Gon no Kami. Unlike Nezumi no soshi, which focuses on the grief of the woman who has unwittingly married a mouse, the Gon no Kami tales contain pronounced comic elements and devote attention to the mouse-groom's perspective. -

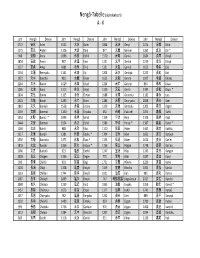

Nihontō Compendium

Markus Sesko NIHONTŌ COMPENDIUM © 2015 Markus Sesko – 1 – Contents Characters used in sword signatures 3 The nengō Eras 39 The Chinese Sexagenary cycle and the corresponding years 45 The old Lunar Months 51 Other terms that can be found in datings 55 The Provinces along the Main Roads 57 Map of the old provinces of Japan 59 Sayagaki, hakogaki, and origami signatures 60 List of wazamono 70 List of honorary title bearing swordsmiths 75 – 2 – CHARACTERS USED IN SWORD SIGNATURES The following is a list of many characters you will find on a Japanese sword. The list does not contain every Japanese (on-yomi, 音読み) or Sino-Japanese (kun-yomi, 訓読み) reading of a character as its main focus is, as indicated, on sword context. Sorting takes place by the number of strokes and four different grades of cursive writing are presented. Voiced readings are pointed out in brackets. Uncommon readings that were chosen by a smith for a certain character are quoted in italics. 1 Stroke 一 一 一 一 Ichi, (voiced) Itt, Iss, Ipp, Kazu 乙 乙 乙 乙 Oto 2 Strokes 人 人 人 人 Hito 入 入 入 入 Iri, Nyū 卜 卜 卜 卜 Boku 力 力 力 力 Chika 十 十 十 十 Jū, Michi, Mitsu 刀 刀 刀 刀 Tō 又 又 又 又 Mata 八 八 八 八 Hachi – 3 – 3 Strokes 三 三 三 三 Mitsu, San 工 工 工 工 Kō 口 口 口 口 Aki 久 久 久 久 Hisa, Kyū, Ku 山 山 山 山 Yama, Taka 氏 氏 氏 氏 Uji 円 円 円 円 Maru, En, Kazu (unsimplified 圓 13 str.) 也 也 也 也 Nari 之 之 之 之 Yuki, Kore 大 大 大 大 Ō, Dai, Hiro 小 小 小 小 Ko 上 上 上 上 Kami, Taka, Jō 下 下 下 下 Shimo, Shita, Moto 丸 丸 丸 丸 Maru 女 女 女 女 Yoshi, Taka 及 及 及 及 Chika 子 子 子 子 Shi 千 千 千 千 Sen, Kazu, Chi 才 才 才 才 Toshi 与 与 与 与 Yo (unsimplified 與 13 -

From Translation to Adaptation: Chinese Language Texts and Early Modern Japanese Literature

From Translation to Adaptation: Chinese Language Texts and Early Modern Japanese Literature Nan Ma Hartmann Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Nan Ma Hartmann All rights reserved ABSTRACT From Translation to Adaptation: Chinese Language Texts and Early Modern Japanese Literature Nan Ma Hartmann This dissertation examines the reception of Chinese language and literature during Tokugawa period Japan, highlighting the importation of vernacular Chinese, the transformation of literary styles, and the translation of narrative fiction. By analyzing the social and linguistic influences of the reception and adaptation of Chinese vernacular fiction, I hope to improve our understanding of genre development and linguistic diversification in early modern Japanese literature. This dissertation historically and linguistically contextualizes the vernacularization movements and adaptations of Chinese texts in the seventeenth to eighteenth centuries, showing how literary importation and localization were essential stimulants and also a paradigmatic shift that generated new platforms for Japanese literature. Chapter 1 places the early introduction of vernacular Chinese language in its social and cultural contexts, focusing on its route of propagation from the Nagasaki translator community to literati and scholars in Edo, and its elevation from a utilitarian language to an object of literary and political interest. Central figures include Okajima Kazan (1674-1728) and Ogyû Sorai (1666-1728). Chapter 2 continues the discussion of the popularization of vernacular Chinese among elite intellectuals, represented by the Ken’en School of scholars and their Chinese study group, “the Translation Society.” This chapter discusses the methodology of the study of Chinese by surveying a number of primers and dictionaries compiled for reading vernacular Chinese and comparing such material with methodologies for reading classical Chinese. -

No.699 (April Issue)

NBTHK SWORD JOURNAL ISSUE NUMBER 699 April, 2015 Meito Kansho Examination of Important Swords Type: Katana Kinzogan mei: Shikkake Norinaga kore suriage Honnami Koshitsu with kao Owner: NBTHK Length: 2 shaku 3 sun 2 bu (70.3 cm) Sori: 9 bu 1 rin (2.75 cm) Motohaba: 9 bu 7 rin (2.95 cm) Sakihaba: 7 bu 1 rin (2. 15 cm ) Motokasane: 2 bu 3 rin (0.7 cm) Sakikasane : 1 bu 7 rin (0.5 cm) Kissaki length: 1 sun 7 rin (3.25 cm) Nakago length: 6 sun 4 bu (19.4 cm) Nakago sori: 5 rin (0.15 cm) Commentary This is a shinogi-zukuri katana with an ihorimune. It is slightly wide, and the widths at the moto and saki are not much different. The shinogi is wide, there is a slightly high shinogi, a large hiraniku, and a strong or substantial shape. The blade is thin, and there is a large sori and a chu-kissaki. The jihada is itame mixed with mokume and nagare hada, and some parts of the jihada are visible. There are thick dense ji- nie, and some chikei. The hamon is ko-gunome mixed with ko-notare and togari. There are ashi, a dense nioiguchi, slightly uneven nie, some hotsure, frequent kinsuji, niesuji,sunagashi, and small yubashiri.The boshi is midarekomi, the tip is yakizume, and there is hakikake and yubashiri. The nakago is o-suriage. The tip of the nakago is sakikiri, and the yasurime are katte-sagari. There is a one mekugi ana, and on the ura side, under the mekugi ana, there is a kinzogan-mei, along the center. -

Toru Amano the Experience of Holding Special Exhibitions at BOJ Money Museum

Toru Amano The experience of holding special exhibitions at BOJ Money Museum Actas de la VIII reunión del Comité Internacional de Museos Monetarios y Bancarios (ICOMON) = Proceedings of the 8th Meeting of the International Committee of Money and Banking Museums (ICOMON), Barcelona, 2001. ICOMON. - Barcelona : Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya, 2003. pp.78-84 Downloaded from: www.icomon.org THE EXPERIENCE OF HOLDING SPECIAL EXHIBITIONS AT BOJ CURRENCY MUSEUM Toru Amano Currency Museum., Bank of Japan Introduction The Bank of Japan Currency Museum opened in 1985 to commemorate the hundredth anniversary of the Bank. The number of items in our collection is around two hundred thousand. Besides Japanese notes and coins from ancient to modern times, our collection includes foreign currencies, especially those from East Asia, and old documents and tools related to money. The main aim of our museum is to illustrate the history of money in Japan. By exhibiting our collection, especially by showing actual notes and coins, we, as a currency museum within the central bank, want to provide people with an opportunity to think about the functions and roles of money and about its historical background. Based on this concept, we have been holding special exhibitions once a year since 1998 in order to introduce more of our research output and our collection. Through arranging and carrying out these special exhibitions, we have accumulated much know-how and learned various lessons, especially in the field of museum management. Outline of past Special Exhibitions 1st Special Exhibition, 1998: Money and Culture: Treasures of the Sempeikan Collection As this was our first special exhibition, we chose a theme that was deeply related to our museum's origin. -

Creating Heresy: (Mis)Representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-Ryū

Creating Heresy: (Mis)representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-ryū Takuya Hino Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Takuya Hino All rights reserved ABSTRACT Creating Heresy: (Mis)representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-ryū Takuya Hino In this dissertation I provide a detailed analysis of the role played by the Tachikawa-ryū in the development of Japanese esoteric Buddhist doctrine during the medieval period (900-1200). In doing so, I seek to challenge currently held, inaccurate views of the role played by this tradition in the history of Japanese esoteric Buddhism and Japanese religion more generally. The Tachikawa-ryū, which has yet to receive sustained attention in English-language scholarship, began in the twelfth century and later came to be denounced as heretical by mainstream Buddhist institutions. The project will be divided into four sections: three of these will each focus on a different chronological stage in the development of the Tachikawa-ryū, while the introduction will address the portrayal of this tradition in twentieth-century scholarship. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations……………………………………………………………………………...ii Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………iii Dedication……………………………………………………………………………….………..vi Preface…………………………………………………………………………………………...vii Introduction………………………………………………………………………….…………….1 Chapter 1: Genealogy of a Divination Transmission……………………………………….……40 Chapter -

Nengo Alpha.Xlsx

Nengô‐Tabelle (alphabetisch) A ‐ K Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise 1772 安永 An'ei 1521 大永 Daiei 1864 元治 Genji 1074 承保 Jōhō 1175 安元 Angen 1126 大治 Daiji 877 元慶 Genkei 1362 貞治 Jōji * 968 安和 Anna 1096 永長 Eichō 1570 元亀 Genki 1684 貞享 Jōkyō 1854 安政 Ansei 987 永延 Eien 1321 元亨 Genkō 1219 承久 Jōkyū 1227 安貞 Antei 1081 永保 Eihō 1331 元弘 Genkō 1652 承応 Jōō 1234 文暦 Benryaku 1141 永治 Eiji 1204 元久 Genkyū 1222 貞応 Jōō 1372 文中 Bunchū 983 永観 Eikan 1615 元和 Genna 1097 承徳 Jōtoku 1264 文永 Bun'ei 1429 永享 Eikyō 1224 元仁 Gennin 834 承和 Jōwa 1185 文治 Bunji 1113 永久 Eikyū 1319 元応 Gen'ō 1345 貞和 Jōwa * 1804 文化 Bunka 1165 永万 Eiman 1688 元禄 Genroku 1182 寿永 Juei 1501 文亀 Bunki 1293 永仁 Einin 1184 元暦 Genryaku 1848 嘉永 Kaei 1861 文久 Bunkyū 1558 永禄 Eiroku 1329 元徳 Gentoku 1303 嘉元 Kagen 1469 文明 Bunmei 1160 永暦 Eiryaku 650 白雉 Hakuchi 1094 嘉保 Kahō 1352 文和 Bunna * 1046 永承 Eishō 1159 平治 Heiji 1106 嘉承 Kajō 1444 文安 Bunnan 1504 永正 Eishō 1989 平成 Heisei * 1387 嘉慶 Kakei * 1260 文応 Bun'ō 988 永祚 Eiso 1120 保安 Hōan 1441 嘉吉 Kakitsu 1317 文保 Bunpō 1381 永徳 Eitoku * 1704 宝永 Hōei 1661 寛文 Kanbun 1592 文禄 Bunroku 1375 永和 Eiwa * 1135 保延 Hōen 1624 寛永 Kan'ei 1818 文政 Bunsei 1356 延文 Enbun * 1156 保元 Hōgen 1748 寛延 Kan'en 1466 文正 Bunshō 923 延長 Enchō 1247 宝治 Hōji 1243 寛元 Kangen 1028 長元 Chōgen 1336 延元 Engen 770 宝亀 Hōki 1087 寛治 Kanji 999 長保 Chōhō 901 延喜 Engi 1751 宝暦 Hōreki 1229 寛喜 Kanki 1104 長治 Chōji 1308 延慶 Enkyō 1449 宝徳 Hōtoku 1004 寛弘 Kankō 1163 長寛 Chōkan 1744 延享 Enkyō 1021 治安 Jian 985 寛和 Kanna 1487 長享 Chōkyō 1069 延久 Enkyū 767 神護景雲 Jingo‐keiun 1017 寛仁 Kannin 1040 長久 Chōkyū 1239 延応 En'ō -

Money in Modern Japan

Money in Modern Japan Japan is one of the oldest states in the world: in over 2000 years the island nation has slowly and continuously developed culturally, socially, politically and economically into the country that it is today. It is characteristic that Japan never fell under the domination of a foreign power during this time – not until after World War II, however, when it was occupied by the Americans for some years (1945- 1952). That does not mean, of course, that no external influences were adopted. On the contrary: until the end of the Japanese Middle Ages (about 1200-1600), Japan was completely geared towards its great neighbor China. From there it adopted cultural, political and economic achievements, among them also money. Well into the 16th century, the Japanese cast coins following Chinese models. In addition, masses of cash coins (ch'ien) imported from China were in circulation. With the beginning of modern times around 1600, a radical turn around took place. Under the government of the Tokugawa shoguns (the Edo period, 1603-1867) the island nation cut itself off almost completely from the outside world. In this time an independent Japanese culture evolved – and a coinage system of its own, whose principal feature was the simultaneous circulation of a gold and a silver currency. 1 von 12 www.sunflower.ch Japanese Empire, Edo Period, Shogun Tokugawa Ietsugu (1712-1716), Kobankin 1714, Edo Denomination: Kobankin Mint Authority: Shogun Tokugawa Ietsugu Mint: Edo (Tokyo) Year of Issue: 1714 Weight (g): 17.8 Diameter (mm): 69.5 Material: Gold Owner: Deutsche Bundesbank Japan was united towards the end of the 16th century after long years of civil war. -

Encyclopedia of Japanese History

An Encyclopedia of Japanese History compiled by Chris Spackman Copyright Notice Copyright © 2002-2004 Chris Spackman and contributors Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.1 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, with no Front-Cover Texts, and with no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License.” Table of Contents Frontmatter........................................................... ......................................5 Abe Family (Mikawa) – Azukizaka, Battle of (1564)..................................11 Baba Family – Buzen Province............................................... ..................37 Chang Tso-lin – Currency............................................... ..........................45 Daido Masashige – Dutch Learning..........................................................75 Echigo Province – Etō Shinpei................................................................ ..78 Feminism – Fuwa Mitsuharu................................................... ..................83 Gamō Hideyuki – Gyoki................................................. ...........................88 Habu Yoshiharu – Hyūga Province............................................... ............99 Ibaraki Castle – Izu Province..................................................................118 Japan Communist Party – Jurakutei Castle............................................135 -

Encyclopedia of Shinto Chronological Supplement

Encyclopedia of Shinto Chronological Supplement 『神道事典』巻末年表、英語版 Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics Kokugakuin University 2016 Preface This book is a translation of the chronology that appended Shinto jiten, which was compiled and edited by the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University. That volume was first published in 1994, with a revised compact edition published in 1999. The main text of Shinto jiten is translated into English and publicly available in its entirety at the Kokugakuin University website as "The Encyclopedia of Shinto" (EOS). This English edition of the chronology is based on the one that appeared in the revised version of the Jiten. It is already available online, but it is also being published in book form in hopes of facilitating its use. The original Japanese-language chronology was produced by Inoue Nobutaka and Namiki Kazuko. The English translation was prepared by Carl Freire, with assistance from Kobori Keiko. Translation and publication of the chronology was carried out as part of the "Digital Museum Operation and Development for Educational Purposes" project of the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Organization for the Advancement of Research and Development, Kokugakuin University. I hope it helps to advance the pursuit of Shinto research throughout the world. Inoue Nobutaka Project Director January 2016 ***** Translated from the Japanese original Shinto jiten, shukusatsuban. (General Editor: Inoue Nobutaka; Tokyo: Kōbundō, 1999) English Version Copyright (c) 2016 Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University. All rights reserved. Published by the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University, 4-10-28 Higashi, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo, Japan. -

An Introduction to Zen Words and Phrases Translated by Michael D

久須本文雄 Kusumoto Bun’yū (1907-1995) 禅語入門 Zengo nyūmon Tokyo: 大法輪閣 Daihōrin-kaku Co. Ltd., 1982 An Introduction to Zen Words and Phrases Translated by Michael D. Ruymar (Michael Sōru Ruymar) 1 What follows is a translation of Kusumoto Bunyū’s (久須本⽂雄) 1982 book Zengo Nyūmon (禅 語⼊⾨, An Introduction to Zen Words and Phrases, Tokyo: Daihōrin-kaku Co. Ltd.), absent its glossary of monastic terms. The main text consists of 100 words and phrases selected by Dr. Kusumoto for exegesis from a variety of sources, but particularly from classic kōan (Zen case) collections like the Blue Cliff Record, the Gateless Barrier, and the Book of Serenity, as well as from the collected writings or sayings of renowned Zen Masters from both China and Japan, like Zen Masters Linji and Dōgen, or, again, from the poetry of such as Han Shan (Cold Mountain) and others. As a genre, there are numerous books of this kind available in Japan, and I have become familiar with two excellent Zengo texts now available to English readers: (i) Moon by The Window: The calligraphy and Zen insights of Shodo Harada (Wisdom Publications, 2011), !and (ii) Zen Words Zen Calligraphy (Tankosha, 1991). It is evident from the breadth and depth of his commentaries that Dr. Kusumoto brought a lifetime of study to bear on the matter contained herein. Though sketchy, he was born in 1908 and graduated in 1933 from what is now Hanazono University, one of several prestigious institutions at which he was destined to lecture in his areas of specialization: Chinese philosophy and Zen studies.