Deconstructing `Japan'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Interpreter

Japan: grasping for hope in a new imperial era | The Interpreter https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/japan-grasping-hope-ne... Tets Kimura Japan has three New Year’s Days this year. 1 January, the calendar new year was the obvious beginning, then followed 1 April, the start of the financial and academic year that is famously symbolised by seasonal cherry blossoms – and now 1 May, the once-only celebration of the first day of what will be known as the Reiwa era of imperial reign. The transition from the current Heisei era to the next era of Reiwa will occur as the Reigning Emperor has decided to abdicate his position to the Crown Prince, even though this was not constitutionally permissible. No Emperor has stepped down from the position in Japan in the last 200 years, but it was the Emperor’s wish to do so as he found it difficult to be responsible in his role at his age. He is 85. Tuesday will be his last day as the Emperor, and under the “one generation, one title” rule, the era of Heisei will consequently end. According to the newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun, 58% of Japanese think Japan will move to a better direction in the new era of Reiwa, whereas 17% see a negative future. The current era of Heisei started on 8 January 1989, a day after the Showa Emperor passed away. When the dramatic Showa era (1926-1989) ended, a time in which Japan experienced wars, the Allied Occupation, and the rapid post- Second World War recovery, Japan decided to name the following imperial reign period Heisei. -

Collecting Karamono Kodō 唐物古銅 in Meiji Japan: Archaistic Chinese Bronzes in the Chiossone Museum, Genoa, Italy

Transcultural Perspectives 4/2020 - 1 Gonatella Failla "ollecting karamono kod( 唐物古銅 in Mei3i Japan: Archaistic Chinese 4ronzes in the Chiossone Museum, Genoa, Ital* Introduction public in the special e>hibition 7ood for the The Museum of Oriental Art, enoa, holds the Ancestors, 7lo#ers for the ods: Transformations of !apanese and Chinese art collections #hich Edoardo Archaistic 4ronzes in China and !apan01 The e>hibits Chiossone % enoa 1833-T()*( 1898) -athered during #ere organised in 5ve main cate-ories: archaistic his t#enty-three-year sta* in !apan, from !anuary copies and imitations of archaic ritual 2ronzes; 1875 until his death in April 1898. A distinguished 4uddhist ritual altar sets in archaistic styleC )aramono professor of design and engraving techniques, )od( hanaike, i.e0 Chinese @o#er 2ronzes collected in Chiossone #as hired 2* the Meiji -overnment to !apan; Chinese 2ronzes for the scholar’s studioC install modern machinery and esta2lish industrial !apan’s reinvention of Chinese archaismB 2ronze and production procedures at the Imperial Printing iron for chanoyu %tea ceremony), for 2unjincha %tea of 4ureau, T()*(, to instruct the youn- -eneration of the literati,, and for @o#er arrangement in the formal designers and engravers, and to produce securit* rik)a style0 printed products such as 2anknotes, state 2ond 4esides documenting the a-es-old, multifaceted certificates, monopoly and posta-e stamps. He #as interest of China in its o#n antiquit* and its unceasing #ell-)no#n also as a portraitist of contemporaneous revivals, the Chiossone 2ronze collection attests to historic 5-ures, most nota2ly Philipp-7ranz von the !apanese tradition of -athering Chinese 2ronzes 9ie2old %1796-1866, and Emperor Meiji %1852-1912, r. -

Jichihan and the Restoration and Innovation of Buddhist Practice

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1999 26/1-2 Jichihan and the Restoration and Innovation of Buddhist Practice Marc Buijnsters The various developments in doctrinal thought and practice during the Insei and Kamakura periods remain one of the most intensively researched fields in the study of Japanese Buddhism. Two of these developments con cern the attempts to restore the observance of traditional Buddhist ethics, and the problem of how Pure La n d tenets could be inserted into the esoteric teaching. A pivotal role in both developments has been attributed to the late-Heian monk Jichihan, who was lauded by the renowned Kegon scholar- monk Gydnen as “the restorer of the traditional precepts ” and patriarch of Japanese Pure La n d Buddhism.,’ At first glance, available sources such as Jichihan’s biograpmes hardly seem to justify these praises. Several newly discovered texts and a more extensive use of various historical sources, however, should make it possible to provide us with a much more accurate and complete picture of Jichihan’s contribution to the restoration and innovation of Buddhist practice. Keywords: Jichihan — esoteric Pure Land thousfht — Buddhist reform — Buddhist precepts As was n o t unusual in the late Heian period, the retired Regent- Chancellor Fujiwara no Tadazane 藤 原 忠 実 (1078-1162) renounced the world at the age of sixty-three and received his first Buddnist ordi nation, thus entering religious life. At tms ceremony the priest Jichi han officiated as Teacher of the Precepts (kaishi 戒自帀;Kofukuji ryaku 興福寺略年代記,Hoen 6/10/2). Fujiwara no Yorinaga 藤原頼長 (1120-11^)0), Tadazane^ son who was to be remembered as “Ih e Wicked Minister of the Left” for his role in the Hogen Insurrection (115bハ occasionally mentions in his diary that he had the same Jichi han perform esoteric rituals in order to recover from a chronic ill ness, achieve longevity,and extinguish his sins (Taiki 台gd Koji 1/8/6, 2/2/22; Ten,y6 1/6/10). -

Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei

Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei By ©2016 Alison Miller Submitted to the graduate degree program in the History of Art and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Maki Kaneko ________________________________ Dr. Sherry Fowler ________________________________ Dr. David Cateforis ________________________________ Dr. John Pultz ________________________________ Dr. Akiko Takeyama Date Defended: April 15, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Alison Miller certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Maki Kaneko Date approved: April 15, 2016 ii Abstract This dissertation examines the political significance of the image of the Japanese Empress Teimei (1884-1951) with a focus on issues of gender and class. During the first three decades of the twentieth century, Japanese society underwent significant changes in a short amount of time. After the intense modernizations of the late nineteenth century, the start of the twentieth century witnessed an increase in overseas militarism, turbulent domestic politics, an evolving middle class, and the expansion of roles for women to play outside the home. As such, the early decades of the twentieth century in Japan were a crucial period for the formation of modern ideas about femininity and womanhood. Before, during, and after the rule of her husband Emperor Taishō (1879-1926; r. 1912-1926), Empress Teimei held a highly public role, and was frequently seen in a variety of visual media. -

The Japanese Religio-Cultural Context

CHAPTER TWO THE JAPANESE RELIGIO-CULTURAL CONTEXT Introduction This chapter introduces three factors that provide essential background information for my investigation into Endo’s theology of inculturation. First, I give a historical sketch of Japanese religion. Secondly, I look at different types of Shinto and clarify aspects of koshinto that inform contemporary Japanese culture. This is important as koshinto with its modern, psychological, and spiritual meanings is the type of Shinto that I observe in Endo’s attempts at inculturation. In connection with this I introduce the Japanese concept of the ‘divine’, and its role in the history of Shinto-Buddhist-Christian relationships. I also go on to propose that koshinto plays a fundamental role in shaping both different types of womanhood in Japan and the negative theology that forms a background to Endo’s type of inculturation. Outline of Features in Japanese Religious History Japan’s indigenous faith is Shinto, which has its roots in the age prior to 300 B.C. The animistic beliefs of this primal religion developed into a community religion with local shrines for household and guardian gods, where people worshipped the divine spirits. Gradually people began to worship ideal kami, personal kami and ancestorial kami.1 This form of Shinto is frequently called ‘proto-shinto’. Confucianism was introduced to Japan near the beginning of the 5th century as a code of moral precepts rather than a religion.2 Buddhism came to Japan from India 1 The Japanese word kami is usually translated into English by the term deity, deities, spirits, or gods. Kami in Japanese can be singular and/or plural. -

Japan's Inland Sea , Setouchi Setouchi, Which Is Celebrated As

Japan's Inland Sea, Setouchi Spectacular Seto Inland Sea A vast, calm sea and islands as far as the eye can see. The Seto Inland Sea, which is celebrated as "The Aegean Sea of the East," is blessed with nature and gentle light. It has a beautiful way of life, and the culture created by locals is still alive. Art, activities, beautiful scenery and the food of this place with a warm climate are all part of the appeal. Each experience you have here is sure to become a special memory. 2 3 Hiroshima Okayama Seto Inland Sea Hiroshima is the central city of Chugoku The Okayama area has flourished region. Hiroshima Prefecture is dotted as an area alive with various culture with Itsukushima Shrine, which has an including swords, Bizen ware and Area Information elegant torii gate standing in the sea; the other handicrafts. Because of its Atomic Bomb Dome that communicates Tottori Prefecture warm climate, fruits such as peaches the importance of peace; and many and muscat grapes are actively other attractions worth a visit. It also grown there. It is also dotted with has world-famous handicrafts such as places where you can see the islands Kumano brushes. of the Seto Inland Sea. Photo taken by Takemi Nishi JAPAN Okayama Hyogo Shimane Prefecture Prefecture Prefecture Fukuoka Sea of Japan Seto Inland Sea Airport Kansai International Airport Setouchi Hiroshima Area Prefecture Seto Inland Sea Hyogo Hyogo Prefecture is roughly in the center of the Japanese archipelago. Hiroshima It has the Port of Kobe, which plays Yamaguchi Port an important role as the gateway of Prefecture Kagawa Prefecture Japan. -

Geography & Climate

Web Japan http://web-japan.org/ GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE A country of diverse topography and climate characterized by peninsulas and inlets and Geography offshore islands (like the Goto archipelago and the islands of Tsushima and Iki, which are part of that prefecture). There are also A Pacific Island Country accidented areas of the coast with many Japan is an island country forming an arc in inlets and steep cliffs caused by the the Pacific Ocean to the east of the Asian submersion of part of the former coastline due continent. The land comprises four large to changes in the Earth’s crust. islands named (in decreasing order of size) A warm ocean current known as the Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, and Shikoku, Kuroshio (or Japan Current) flows together with many smaller islands. The northeastward along the southern part of the Pacific Ocean lies to the east while the Sea of Japanese archipelago, and a branch of it, Japan and the East China Sea separate known as the Tsushima Current, flows into Japan from the Asian continent. the Sea of Japan along the west side of the In terms of latitude, Japan coincides country. From the north, a cold current known approximately with the Mediterranean Sea as the Oyashio (or Chishima Current) flows and with the city of Los Angeles in North south along Japan’s east coast, and a branch America. Paris and London have latitudes of it, called the Liman Current, enters the Sea somewhat to the north of the northern tip of of Japan from the north. The mixing of these Hokkaido. -

Tourists in Paradise Writing the Pure Land in Medieval Japanese Fiction

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 33/2: 269–296 © 2006 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture R. Keller Kimbrough Tourists in Paradise Writing the Pure Land in Medieval Japanese Fiction Late-medieval Japanese fiction contains numerous accounts of lay and monastic travelers to the Pure Land and other extra-human realms. In many cases, the “tourists” are granted guided tours, after which they are returned to the mun- dane world in order to tell of their unusual experiences. This article explores several of these stories from around the sixteenth century, including, most prominently, Fuji no hitoana sōshi, Tengu no dairi, and a section of Seiganji engi. I discuss the plots and conventions of these and other narratives, most of which appear to be based upon earlier oral tales employed in preaching and fund-raising, in order to illuminate their implications for our understanding of Pure Land-oriented Buddhism in late-medieval Japan. I also seek to demon- strate the diversity and subjectivity of Pure Land religious experience, and the sometimes startling gap between orthodox doctrinal and popular vernacular representations of Pure Land practices and beliefs. keywords: otogizōshi – jisha engi – shaji engi – Fuji no hitoana sōshi – Bishamon no honji – Tengu no dairi – Seiganji engi – hell – travel R. Keller Kimbrough is an assistant professor of Japanese Literature at the University of Colorado at Boulder. 269 ccording to an anonymous work of fifteenth- or early sixteenth- century Japanese fiction by the name of Chōhōji yomigaeri no sōshi 長宝 寺よみがへりの草紙 [Back from the dead at Chōhōji Temple], the Japa- Anese Buddhist nun Keishin dropped dead on the sixth day of the sixth month of Eikyō 11 (1439), made her way to the court of King Enma, ruler of the under- world, and there received the King’s personal religious instruction and a trau- matic tour of hell. -

I TEAM JAPAN: THEMES of 'JAPANESENESS' in MASS MEDIA

i TEAM JAPAN: THEMES OF ‘JAPANESENESS’ IN MASS MEDIA SPORTS NARRATIVES A Dissertation submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Michael Plugh July 2015 Examining Committee Members: Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Nancy Morris, Media and Communication Doctoral Program John Campbell, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Lance Strate, External Member, Fordham University ii © Copyright 2015 by MichaelPlugh All Rights Reserved iii Abstract This dissertation concerns the reproduction and negotiation of Japanese national identity at the intersection between sports, media, and globalization. The research includes the analysis of newspaper coverage of the most significant sporting events in recent Japanese history, including the 2014 Koshien National High School Baseball Championships, the awarding of the People’s Honor Award, the 2011 FIFA Women’s World Cup, wrestler Hakuho’s record breaking victories in the sumo ring, and the bidding process for the 2020 Olympic Games. 2054 Japanese language articles were examined by thematic analysis in order to identify the extent to which established themes of “Japaneseness” were reproduced or renegotiated in the coverage. The research contributes to a broader understanding of national identity negotiation by illustrating the manner in which established symbolic boundaries are reproduced in service of the nation, particularly via mass media. Furthermore, the manner in which change is negotiated through processes of assimilation and rejection was considered through the lens of hybridity theory. iv To my wife, Ari, and my children, Hiroto and Mia. Your love sustained me throughout this process. -

Dept of History Draft Syllabus (Cbcs)

RAJA NARENDRALAL KHAN WOMEN’S COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) DEPT OF HISTORY DRAFT SYLLABUS (CBCS) I SEMESTER Course Course Title Credit Marks Total Th IM AM CC1T Greek and Roman Historians 6 60 10 5 75 CC2T Early Historic India 6 60 10 5 75 GE1T History of India From the earliest 6 60 10 5 75 times to C 300 BCE DSC History of India-I (Ancient India) 6 60 10 5 75 CC-1: Greek and Roman Historians C1T: Greek and Roman Historians Unit-I Module I New form of inquiry (historia) in Greece in the sixth century BCE 1.1 Logographers in ancient Greece. 1.2 Hecataeus of Miletus, the most important predecessor of Heredotus 1.3 Charon of Lampsacus 1.4 Xanthus of Lydia Module II Herodotus and his Histories 2.1 A traveller’s romance? 2.2 Herodotus’ method of history writing – his catholic inclusiveness 2.3 Herodotus’ originality as a historian – focus on the struggle between the East and the West Module III Thucydides: the founder of scientific history writing 3.1 A historiography on Thucydides 3.2 History of the Peloponnesian War - a product of rigorous inquiry and examination 3.3 Thucydides’ interpretive ability – his ideas of morality, Athenian imperialism, culture and democratic institutions 3.4 Description of plague in a symbolic way – assessment of the demagogues 3.5 A comparative study of the two greatest Greek historians Module IV Next generation of Greek historians 4.1 Xenophon and his History of Greece (Hellenica) 4.2 a description of events 410 BCE – 362 BCE 4.3 writing in the style of a high-class journalist – lack of analytical skill 4.5 Polybius and the “pragmatic” history 4.3 Diodorus Siculus and his Library of History – the Stoic doctrine of the brotherhood of man Unit II Roman Historiography Module I Development of Roman historiographical tradition 1.1 Quintus Fabius Pictor of late third century BCE and the “Graeci annals” – Rome’s early history in Greek. -

The Technological Imaginary of Imperial Japan, 1931-1945

THE TECHNOLOGICAL IMAGINARY OF IMPERIAL JAPAN, 1931-1945 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Aaron Stephen Moore August 2006 © 2006 Aaron Stephen Moore THE TECHNOLOGICAL IMAGINARY OF IMPERIAL JAPAN, 1931-1945 Aaron Stephen Moore, Ph.D. Cornell University 2006 “Technology” has often served as a signifier of development, progress, and innovation in the narrative of Japan’s transformation into an economic superpower. Few histories, however, treat technology as a system of power and mobilization. This dissertation examines an important shift in the discourse of technology in wartime Japan (1931-1945), a period usually viewed as anti-modern and anachronistic. I analyze how technology meant more than advanced machinery and infrastructure but included a subjective, ethical, and visionary element as well. For many elites, technology embodied certain ways of creative thinking, acting or being, as well as values of rationality, cooperation, and efficiency or visions of a society without ethnic or class conflict. By examining the thought and activities of the bureaucrat, Môri Hideoto, and the critic, Aikawa Haruki, I demonstrate that technology signified a wider system of social, cultural, and political mechanisms that incorporated the practical-political energies of the people for the construction of a “New Order in East Asia.” Therefore, my dissertation is more broadly about how power operated ideologically under Japanese fascism in ways other than outright violence and repression that resonate with post-war “democratic” Japan and many modern capitalist societies as well. This more subjective, immaterial sense of technology revealed a fundamental ambiguity at the heart of technology. -

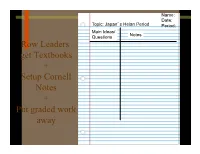

7.5 Heian Notes

Name: Date: Topic: Japan’s Heian Period Period: Main Ideas/ Questions Notes Row Leaders get Textbooks + Setup Cornell Notes + Put graded work away A New Capital • In 794, the Emperor Kammu built a new capital city for Japan, called Heian-Kyo. • Today, it is called Kyoto. • The Heian Period is called Japan’s “Golden Age” Essential Question: What does “Golden Age” mean? Inside the city • Wealthy families lived in mansions surrounded by gardens. A Powerful Family • The Fujiwara family controlled Japan for over 300 years. • They had more power than the emperor and made important decisions for Japan. Beauty and Fashion • Beauty was important in Heian society. • Men and women blackened their teeth. • Women plucked their eyebrows and painted them higher on their foreheads. Beauty and Fashion • Heian women wore as many as 12 silk robes at a time. • Long hair was also considered beautiful. Entertainment • The aristocracy had time for diversions such as go (a board game), kemari (keep the ball in play) and bugaku theater. Art • Yamato-e was a style of Japanese art that reflected nature from the Japanese religion of Shinto. Writing and Literature • The Tale of Genji was written by Murasaki Shikibu, a woman, and is considered the world’s first novel. Japanese Origami Book Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. .