Awkward Encounters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Israel's National Religious and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict

Leap of Faith: Israel’s National Religious and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict Middle East Report N°147 | 21 November 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iv I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Religious Zionism: From Ascendance to Fragmentation ................................................ 5 A. 1973: A Turning Point ................................................................................................ 5 B. 1980s and 1990s: Polarisation ................................................................................... 7 C. The Gaza Disengagement and its Aftermath ............................................................. 11 III. Settling the Land .............................................................................................................. 14 A. Bargaining with the State: The Kookists ................................................................... 15 B. Defying the State: The Hilltop Youth ........................................................................ 17 IV. From the Hills to the State .............................................................................................. -

CV July 2017

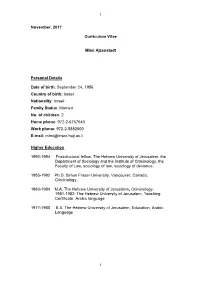

1 November, 2017 Curriculum Vitae Mimi Ajzenstadt Personal Details Date of birth: September 24, 1956 Country of birth: Israel Nationality: Israeli Family Status: Married No. of children: 2 Home phone: 972-2-6767540 Work phone: 972-2-5882600 E-mail: [email protected] Higher Education 1992-1994 Post-doctoral fellow, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the Department of Sociology and the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law, sociology of law, sociology of deviance. 1985-1992 Ph.D. Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, Canada, Criminology. 1980-1984 M.A. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Criminology. 1981-1982: The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Teaching Certificate, Arabic language 1977-1980 B.A. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Education, Arabic Language 1 2 Appointments at the Hebrew University 2012- present Full Professor, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work and Social Welfare. 2007– 2012 Associate Professor, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work and Social Welfare. 2002- 2007 Senior Lecturer, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work and Social Welfare. 1994-2002 Lecturer, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work. Service in other Academic Institutions Summer, 2011 Visiting Professor, Cambridge University. Summer, 2010 Visiting Professor. University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada. 2005 -2006 Visiting Professor. University of Maryland, Maryland, USA. Winter, 2000 Visiting Scholar. Stockholm University, Sweden. Fall 1999 Visiting Scholar. Yale University, New-Haven, Connecticut, U.S.A., Law School. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-13864-3 — the Israeli Settler Movement Sivan Hirsch-Hoefler , Cas Mudde Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-13864-3 — The Israeli Settler Movement Sivan Hirsch-Hoefler , Cas Mudde Index More Information Index 1948 Arab–Israeli War, the, 2 Ariel, Uri, 76, 116 1949 Armistice Agreements, the, 2 Arutz Sheva, 120–121, 154, 205 1956 Sinai campaign, the, 60 Ashkenazi, 42, 64, 200 1979 peace agreement, the, 57 Association for Retired People, 23 Australia, 138 Abrams, Eliott, 59 Aviner, Shlomo, 65, 115, 212 Academic Council for National, the. See Professors for a Strong Israel B’Sheva, 120 action B’Tselem, 36, 122 connective, 26 Barak, Ehud, 50–51, 95, 98, 147, 235 extreme, 16 Bar-Ilan University, 50, 187 radical, 16 Bar-Siman-Tov, Yaacov, 194, 216 tactical, 34 Bat Ayin Underground, the, 159 activism BDS. See Boycott, Divestment and moderate, 15–16 Sanctions transnational, 30–31 Begin, Manahem, 47, 48, 118–119, Adelson, Sheldon, 179, 190 157, 172 Airbnb, 136 Beit El, 105 Al Aqsa Mosque, the, 146 Beit HaArava, 45 Al-Aqsa Intifada. See the Second Intifada Beitar Illit, 67, 70, 99 Alfei Menashe, 100 Beitar Ironi Ariel, 170 Allon, Yigal, 45–46 Belafonte, Harry, 14 Alon Shvut, 88, 190 Ben Ari, Michael, 184 Aloni, Shulamit, 182 Bendaña, Alejandro, 24 Altshuler, Amos, 189 Ben-Gurion, David, 46 Amana, 76–77, 89, 113, 148, 153–154, 201 Ben-Gvir, Itamar, 184 American Friends of Ariel, 179–180 Benn, Menachem, 164 American Studies Association, 136 Bennett, Naftali, 76, 116, 140, 148, Amnesty International, 24 153, 190 Amona, 79, 83, 153, 157, 162, 250, Benvenisti, Meron, 1 251 Ben-Zimra, Gadi, 205 Amrousi, Emily, 67, 84 Ben-Zion, -

Religious Zionism Survey

RESULTS FROM THE COMPREHENSIVE SURVEY Modern Dati Haredi Leumi Orthodox Leumi (“Hardal”) OF RELIGIOUS ZIONISM [ Religious self-identification * ] The goal of this survey is to take a close look at Israel’s Religious Zionist community, and determine how the members of this community resemble and differ from each other on various issues. The findings of the survey are based on a sampling of 3,416 Israeli residents who responded to the survey online. The percentage values in the graphs and tables represent how many respondents highly agreed with the statement (on a scale of 1- 10). COMMITMENT TO HALACHA 80.1% 95.8% 82.6% { { Commitment to 56.4% 50.7% observing halacha I daven at least 37.9% 01 is an integral part 05 once a day of my identity * only women were asked this question 85.5% 58.4% 73.3% 52.1% { 35.9% 39.1% I daven Shacharit { I set aside time 02 in a minyan 06 for Torah study I regularly davven Shacharit I set aside time every week to study Age Age in a minyan Torah, Gemara and other Jewish subjects 18-25 46.4% 18-25 46.4% 26-35 42.7% 26-35 42.7% 36-45 46.7% 36-45 46.7% 46-55 55.4% 46-55 55.4% 56-65 54% 56-65 54% Over 66 73.3% Over 66 73.3% * only men were asked this question 92.5% 76.3% { 53.2% 33.1% It is permissible { 19.3% to eat at a coee shop Halachah is 6.1% 07 only if it has a valid 03 too rigid kashrut certication 95.2% 72.1% 86.5% { Would I have chosen to be 04 religious? RESULTS FROM THE COMPREHENSIVE SURVEY Modern Dati Haredi Leumi Orthodox Leumi (“Hardal”) OF RELIGIOUS ZIONISM [ Religious self-identification * ] The goal of this survey is to take a close look at Israel’s Religious Zionist community, and determine how the members of this community resemble and differ from each other on various issues. -

Republication, Copying Or Redistribution by Any Means Is

Republication, copying or redistribution by any means is expressly prohibited without the prior written permission of The Economist The Economist April 5th 2008 A special report on Israel 1 The next generation Also in this section Fenced in Short-term safety is not providing long-term security, and sometimes works against it. Page 4 To ght, perchance to die Policing the Palestinians has eroded the soul of Israel’s people’s army. Page 6 Miracles and mirages A strong economy built on weak fundamentals. Page 7 A house of many mansions Israeli Jews are becoming more disparate but also somewhat more tolerant of each other. Page 9 Israel at 60 is as prosperous and secure as it has ever been, but its Hanging on future looks increasingly uncertain, says Gideon Licheld. Can it The settlers are regrouping from their defeat resolve its problems in time? in Gaza. Page 11 HREE years ago, in a slim volume enti- abroad, for Israel to become a fully demo- Ttled Epistle to an Israeli Jewish-Zionist cratic, non-Zionist state and grant some How the other fth lives Leader, Yehezkel Dror, a veteran Israeli form of autonomy to Arab-Israelis. The Arab-Israelis are increasingly treated as the political scientist, set out two contrasting best and brightest have emigrated, leaving enemy within. Page 12 visions of how his country might look in a waning economy. Government coali- the year 2040. tions are fractious and short-lived. The dif- In the rst, it has some 50% more peo- ferent population groups are ghettoised; A systemic problem ple, is home to two-thirds of the world’s wealth gaps yawn. -

Modern Orthodoxy and the Road Not Taken: a Retrospective View

Copyrighted material. Do not duplicate. Modern Orthodoxy and the Road Not Taken: A Retrospective View IRVING (YITZ) GREENBERG he Oxford conference of 2014 set off a wave of self-reflection, with particu- Tlar reference to my relationship to and role in Modern Orthodoxy. While the text below includes much of my presentation then, it covers a broader set of issues and offers my analyses of the different roads that the leadership of the community and I took—and why.1 The essential insight of the conference was that since the 1960s, Modern Orthodoxy has not taken the road that I advocated. However, neither did it con- tinue on the road it was on. I was the product of an earlier iteration of Modern Orthodoxy, and the policies I advocated in the 1960s could have been projected as the next natural steps for the movement. In the course of taking a different 1 In 2014, I expressed appreciation for the conference’s engagement with my think- ing, noting that there had been little thoughtful critique of my work over the previous four decades. This was to my detriment, because all thinkers need intelligent criticism to correct errors or check excesses. In the absence of such criticism, one does not learn an essential element of all good thinking (i.e., knowledge of the limits of these views). A notable example of a rare but very helpful critique was Steven Katz’s essay “Vol- untary Covenant: Irving Greenberg on Faith after the Holocaust,” inHistoricism, the Holocaust, and Zionism: Critical Studies in Modern Jewish Thought and History, ed. -

Phenomenon, Vigilantism, and Rabbi Yitzchak Ginsburgh's

‘THE SIMPLE JEW’: THE ‘PRICE TAG’ PHENOMENON, VIGILANTISM, AND RABBI YITZCHAK GINSBURGH’S POLITICAL KABBALAH Tessa Satherley* ABSTRACT: This paper explores the Kabbalistic theosophy of Rabbi Yitzchak Ginsburgh, and allegations of links between his yeshiva and violent political activism and vigilantism. Ginsburgh is head of the yeshiva Od Yosef Chai (Joseph Still Lives) in Samaria/the northern West Bank. His students and colleagues have been accused by the authorities of violence and vandalism against Arabs in the context of ‘price tag’ actions and vigilante attacks, while publications by Ginsburgh and his yeshiva colleagues such as Barukh HaGever (Barukh the Man/Blessed is the Man) and Torat HaMelekh (The King’s Torah) have been accused of inciting racist violence. This paper sketches the yeshiva’s history in the public spotlight and describes the esoteric, Kabbalistic framework behind Ginsburgh’s politics, focusing on his political readings of Zoharic Kabbalah and teachings about the mystical value of spontaneous revenge attacks by ‘the simple Jew’, who acts upon his feelings of righteous indignation without prior reflection. The conclusion explores and attempts to delimit the explanatory power of such mystical teachings in light of the sociological characteristics of the Hilltop Youth most often implicated as price tag ‘operatives’ and existing scholarly models of vigilantism. It also points to aspects of the mystical teachings with potential for special potency in this context. Rabbi Yitzchak Ginsburgh (1944-) is a Chabad rabbi and head of the Od Yosef Chai (Joseph Still Lives) yeshiva in the Yitzhar settlement, near the major Palestinian population centre of Nablus (biblical Shechem). The yeshiva occupies an unusual discursive space – neither mainstream religious Zionist (though some of its teaching staff were educated in this tradition) nor formally affiliated with the Hasidic movement, despite Ginsburgh’s own affiliation with Chabad and despite his teachings being steeped in its Kabbalistic inheritance. -

The Disengagement: an Ideological Crisis – Cont

JAFFEE CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES TEL AVIV UNIVERSITY Volume 7, No. 4 March 2005 The Disengagement: Also in this Issue An Ideological Crisis The Election of Abu Mazen Yehuda Ben Meir and the Next Stage in Israeli–Palestinian Relations Mark A. Heller n he idea of the Greater Land of Israel has been central to the ideological, public, and in many cases personal lives of a large number of Israelis for more than thirty years. For them, Israel’s disengagement plan repre- Israel and NATO: Tsents a moment of truth and a point of no return. This plan has unquestionably Opportunities and Risks triggered a profound crisis, challenging and destabilizing many of the truths underlying their world view. An important aspect of this crisis stems from the Zaki Shalom fact that the architect and leader of the disengagement is none other than Ariel Sharon, who until recently served as the community’s chief patron. The crisis n is likely to have far-reaching repercussions. This article will assess the scope of the crisis and its implications, primarily The Recent American for this community but also with an eye to Israeli society as a whole. The threat of civil war has been mentioned more than once, and government ministers, Intelligence Failures Knesset members, and public leaders from various circles regularly discuss the Ephraim Kam need to forestall this possibility. It is therefore important to emphasize from the outset that there is no danger of civil war. In some cases, use of the term n "civil war" reflects attempts to frighten and threaten the general public in order to reduce support for the disengagement. -

The Challenge of Halakhic Innovation

The Challenge of Halakhic Innovation Benjamin Lau Bio: Rabbi Dr. Benjamin Lau is director of the Center for Judaism and Society and the founder of the Institute for Social Justice, both at Beit Morasha of Jerusalem. He is Rabbi of the Ramban synagogue in Jerusalem, and author of a multi-volume Hebrew series, Hakhimim, which was recently published in English as The Sages. Abstract: This article defines a vision of halakhah and the rabbinate that identifies with modern life and works to advance religious life within Israel and Western societies. It argues for a halakhah and a rabbinate that is sensitive to Kelal Yisrael, Zionism and Israeli democracy, the interests of women, the handicapped and that can speak to all Jews. It wishes to return Torah its original domain—every aspect of human life. A Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse Orthodox Modern of Forum A The author rejects the superiority of halakhic stringency and advocates M e o r o t the use of hiddush to confront the realities of modern life, seeing the former as traditional halakhic methodology. Meorot 8 Tishrei 5771 © 2010 A Publication of Yeshivat Chovevei Torah Rabbinical School The Challenge of Halakhic Innovation* Benjamin Lau “Torah Blends Well With the Land”: Modernity as a Value in the World of Torah This article1 is written following an extended broken out among various streams of Religious series of attacks against the segment of the Zionism, and most recently the modern stream religious community and its rabbinic leadership has been classified as ―neo-reformers.‖ Not that identifies with modernity and works to content with that terminology, the (right wing) advance halakhic life within the Israeli and advocates have sought to follow in the path of Western context. -

The Role of Religious Considerations in the Discussion of Women's Combat Service—The Case Of

religions Article The Pink Tank in the Room: The Role of Religious Considerations in the Discussion of Women’s Combat Service—The Case of the Israel Defense Forces Elisheva Rosman Department of Political Studies, Bar Ilan University, Ramat Gan 5290002, Israel; [email protected] Received: 5 October 2020; Accepted: 21 October 2020; Published: 27 October 2020 Abstract: Women serve in diverse roles in the 21st century militaries of the world. They are no longer banned from combat. The presence of women on the battlefield has raised religious arguments and considerations. What role do religious arguments play in the discussion regarding women’s military service? Using media, internal publications, as well as academic articles, the current paper examined this question in the context of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF): a conscription-based military that conscripts both men and women, religious and secular, for both combat and noncombat postings. Using the case of the pilot program in the IDF attempting to integrate women in the Israeli tank corps, as well as gauging the way religious men view this change, the paper argues that religious considerations serve the same purpose as functional considerations and can be amplified or lessened, as needed. Keywords: military; IDF; female soldiers; religion and the military; religious considerations; religious women’s conscription In November 2016, the issue of integrating women in the IDF (Israel Defense Forces) tank corps began to be discussed. The Israeli national religious caricaturist Yossi Shachar published a caricature of a large pink tank, labeled “feminism”, threatening a small tank with a frightened solider inside it, labeled “the IDF” (Shachar 2016). -

A Sephardic Perspective: Addressing Social and Religious Divides Within Israeli Society

A Sephardic Perspective: Addressing Social and Religious Divides within Israeli Society Byline: Isaac Chouraqui and David Zenou Social gaps, between different groups and populations, are a fundamental problem that the State of Israel grapples with today. In many cases these divisions are physical as seen in many Israeli neighborhoods and communities where diverse populations live separately, refusing to integrate and live together. These rifts are evident in many walks of Israeli life, and what is common amongst all of these social gaps is that they cause extreme isolation and social alienation between people living in the same society. Thus we find a strong divide between religious and non-religious as well as a plethora of identities on the spectrum between ultra orthodox and secular: Nationalist-Ultra Orthodox (Hardal), National Religious, Traditionalist, Reform, those who see Judaism as a culture and .a small group of those considered strictly secular In addition to this, other aspects of identity complicate these social divides. For instance, there are divisions based on ethnicity in Israeli society. Sadly, more than 60 years after the inception of the State of Israel, country of origin is still sociologically meaningful when trying to understand divisions within Israeli society. Two different groups can be distinguished amongst Israelis: those whose roots originate in Europe and the United States and those whose roots are found in Asia and Africa. Even for those who are second and third generations Israelis, individuals who were born in Israel or whose parents were born in Israel, ethnic origin plays a significant role. One might expect religious identity to function as a unifying force for the Jewish people, because this identity might bring Jews of different ethnic backgrounds together, despite diverse countries of origin and denominations. -

Rabbi Tzvi Yisrael Tau & Rabbi Yitzchak Ginsburgh

Unity and opposites in Israel’s settler movement: Rabbi Tzvi Yisrael Tau & Rabbi Yitzchak Ginsburgh Tessa Dawn Satherley Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2015 School of Historical and Philosophical Studies The University of Melbourne Produced on archival quality paper. 1 Abstract The thesis is motivated by the central question: can deep engagement with the nuances of contemporary settler religious discourse guide a more effective approach to negotiations with and about this group, especially regarding the future of “Judea and Samaria,” or “the occupied territories”? To address this, I investigate two key religious thinkers. The first is Rabbi Tzvi Yisrael Tau, a major religious Zionist intellectual and head of the leading mamlakhti1 yeshiva Har Ha-Mor, known for his calls for restraint in the face of anti-settlement policies. The second is Rabbi Yitzchak Ginsburgh of Od Yosef Chai, often accused of inciting racism and encouraging aggressive protest tactics, and whose students have been at the vanguard of anti-Arab vigilante violence and the “price tag” campaign of recent years. This investigation reveals Tau’s predominantly monistic worldview, anchored in the “unity of opposites” paradigm at the heart of Avraham Kook’s teachings, and Ginsburgh’s relatively dualistic worldview, anchored in a dualistic interpretation of lurianic Kabbalah. These distinct symbolic worlds help explain the divergent political– historical interpretations, ethics, and political tactics among the rabbis’ adherents. Moreover, the analysis indicated which pro-negotiation arguments may be most persuasive among these different sectors—and which may be useless or disastrous. I show how Tau argues that settlements are a mere detail in Gush Emunim’s project, identifies Jewish unity as a supreme value, and calls for educational outreach in lieu of protests.