From Marginalization to Bounded Integration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making the Afro-Turk Identity

Vocabularies of (In)Visibilities: (Re)Making the Afro-Turk Identity AYşEGÜL KAYAGIL* Abstract After the abolition of slavery towards the end of the Ottoman Empire, the majority of freed black slaves who remained in Anatolia were taken to state “guesthouses” in a number of cities throughout the Empire, the most im- portant of which was in Izmir. Despite their longstanding presence, the descendants of these black slaves – today, citizens of the Republic of Turkey – have until recently remained invisible both in the official historiography and in academic scholarship of history and social science. It is only since the establishment of the Association of Afro-Turks in 2006 that the black popu- lation has gained public and media attention and a public discussion has fi- nally begun on the legacies of slavery in Turkey. Drawing on in-depth inter- views with members of the Afro-Turk community (2014-2016), I examine the key role of the foundation of the Afro-Turk Association in reshaping the ways in which they think of themselves, their shared identity and history. Keywords: Afro-Turks, Ottoman slavery, Turkishness, blackness Introduction “Who are the Afro-Turks?” has been the most common response I got from my friends and family back home in Turkey, who were puzzled to hear that my doctoral research concerned the experiences of the Afro-Turk commu- nity. I would explain to them that the Afro-Turks are the descendants of en- slaved Africans who were brought to the Ottoman Empire over a period of 400 years and this brief introduction helped them recall. -

Open Seders Will Open Hearts

ב“ה :THIS WEEK’S TOPIC ערב פסח, י׳׳ד ניסן, תש״פ ISSUE The Rebbe’s meetings with 378 Erev Pesach, April 8, 2020 the chief rabbis of Israel For more on the topic, visit 70years.com HERE’S my STORY OPEN SEDERS WILL Generously OPEN HEARTS sponsored by the RABBI YAAKOV SHAPIRA they spoke about activities of the Israeli Rabbinate and the state of Yiddishkeit in Israel; and they discussed the prophecies concerning the coming of the Mashiach and the Final Redemption. They went from topic to topic, without pause, and their conversations were recorded, transcribed and later published. During the first visit in 1983, the Rebbe asked the chief rabbis how they felt being outside of Israel. My father said that he had never left the Holy Land before, and that the time away was very difficult for him. To bring him comfort, the Rebbe expounded on the Torah verse, “Jacob lifted his feet and went to the land of the people of the East,” pointing out that while Jacob’s departure from the Land of Israel was a spiritual descent, y father, Rabbi Avraham Shapira, served as the later it turned out that this descent was for the sake of a MAshkenazi chief rabbi of Israel from 1983 until 1993, greater ascent. All Jacob’s sons — who would give rise to while Rabbi Mordechai Eliyahu served as the Sephardic the Twelve Tribes of Israel — were born outside the Land. chief rabbi. During their tenure they traveled to the United This is why the great 11th century Torah commentator, States three times for the purpose of visiting the central Rashi, reads the phrase “lifted his feet” as meaning Jacob Jewish communities in America and getting to know their “moved with ease” because G-d had promised to protect leaders. -

Reconciling Statism with Freedom: Turkey's Kurdish Opening

Reconciling Statism with Freedom Turkey’s Kurdish Opening Halil M. Karaveli SILK ROAD PAPER October 2010 Reconciling Statism with Freedom Turkey’s Kurdish Opening Halil M. Karaveli © Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program – A Joint Transatlantic Research and Policy Center Johns Hopkins University-SAIS, 1619 Massachusetts Ave. NW, Washington, D.C. 20036 Institute for Security and Development Policy, V. Finnbodav. 2, Stockholm-Nacka 13130, Sweden www.silkroadstudies.org “Reconciling Statism with Freedom: Turkey’s Kurdish Opening” is a Silk Road Paper published by the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute and the Silk Road Studies Program. The Silk Road Papers Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Joint Center, and ad- dresses topical and timely subjects. The Joint Center is a transatlantic independent and non-profit research and policy center. It has offices in Washington and Stockholm and is affiliated with the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies of Johns Hopkins University and the Stockholm-based Institute for Security and Development Policy. It is the first institution of its kind in Europe and North America, and is firmly established as a leading research and policy center, serving a large and diverse commu- nity of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. The Joint Center is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development in the region. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lec- tures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public dis- cussion regarding the region. The opinions and conclusions expressed in this study are those of the authors only, and do not necessarily reflect those of the Joint Center or its sponsors. -

Israel's National Religious and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict

Leap of Faith: Israel’s National Religious and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict Middle East Report N°147 | 21 November 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iv I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Religious Zionism: From Ascendance to Fragmentation ................................................ 5 A. 1973: A Turning Point ................................................................................................ 5 B. 1980s and 1990s: Polarisation ................................................................................... 7 C. The Gaza Disengagement and its Aftermath ............................................................. 11 III. Settling the Land .............................................................................................................. 14 A. Bargaining with the State: The Kookists ................................................................... 15 B. Defying the State: The Hilltop Youth ........................................................................ 17 IV. From the Hills to the State .............................................................................................. -

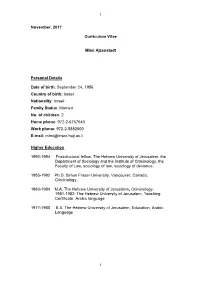

CV July 2017

1 November, 2017 Curriculum Vitae Mimi Ajzenstadt Personal Details Date of birth: September 24, 1956 Country of birth: Israel Nationality: Israeli Family Status: Married No. of children: 2 Home phone: 972-2-6767540 Work phone: 972-2-5882600 E-mail: [email protected] Higher Education 1992-1994 Post-doctoral fellow, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the Department of Sociology and the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law, sociology of law, sociology of deviance. 1985-1992 Ph.D. Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, Canada, Criminology. 1980-1984 M.A. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Criminology. 1981-1982: The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Teaching Certificate, Arabic language 1977-1980 B.A. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Education, Arabic Language 1 2 Appointments at the Hebrew University 2012- present Full Professor, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work and Social Welfare. 2007– 2012 Associate Professor, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work and Social Welfare. 2002- 2007 Senior Lecturer, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work and Social Welfare. 1994-2002 Lecturer, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work. Service in other Academic Institutions Summer, 2011 Visiting Professor, Cambridge University. Summer, 2010 Visiting Professor. University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada. 2005 -2006 Visiting Professor. University of Maryland, Maryland, USA. Winter, 2000 Visiting Scholar. Stockholm University, Sweden. Fall 1999 Visiting Scholar. Yale University, New-Haven, Connecticut, U.S.A., Law School. -

The Fifth Passover Cup and Magical Pairs: Isaac Baer Levinsohn and the Babylonian Talmud

European Journal of Jewish Studies 15 (2021) 84–103 brill.com/ejjs The Fifth Passover Cup and Magical Pairs: Isaac Baer Levinsohn and the Babylonian Talmud Leor Jacobi Abstract The Fifth Passover Cup is mentioned in a textual variant of a baraita in Tractate Pesaḥim of the Babylonian Talmud (118a), attributed to Rabbi Ṭarfon and another anonymous Palestinian tanna. Scholars have demonstrated that the variant is primary in talmu- dic manuscripts and among the Babylonian Geonim. Following a nineteenth-century proposition of Isaac Baer Levinsohn, it is argued that the fifth cup was instituted in Babylonia due to concern for magical evil spirits aroused by even-numbered events [zugot]. Objections to Levinsohn’s theory can be allayed by critical source analysis: the Talmud’s attribution of the fifth cup to the Palestinian tanna Rabbi Ṭarfon in a baraita is pseudoepigraphic, based upon Rabbi Ṭarfon’s teaching regarding the recitation of Hallel ha-Gadol in Mishnah Ta‘anit 3:9. A special appendix is devoted to Levinsohn’s separate study on zugot in the ancient and medieval world. Keywords Talmud – Passover – magic – Haskalah – source criticism – Halakhah – Levinsohn – magical pairs © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/1872471X-bja10020.0102883/ 3..8.31893: The Fifth Passover Cup and Magical Pairs 85 1 Introduction1 If the four Passover cups were created during the six days of creation, then the fifth was conjured up at twilight on the eve of the Sabbath.2 The saga of the mysterious fifth cup stretches from its origins in a phantom talmudic tex- tual variant to its alleged metamorphosis into the ubiquitous “cup of Elijah” to latter-day messianic revival attempts incorporating the visual arts. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-13864-3 — the Israeli Settler Movement Sivan Hirsch-Hoefler , Cas Mudde Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-13864-3 — The Israeli Settler Movement Sivan Hirsch-Hoefler , Cas Mudde Index More Information Index 1948 Arab–Israeli War, the, 2 Ariel, Uri, 76, 116 1949 Armistice Agreements, the, 2 Arutz Sheva, 120–121, 154, 205 1956 Sinai campaign, the, 60 Ashkenazi, 42, 64, 200 1979 peace agreement, the, 57 Association for Retired People, 23 Australia, 138 Abrams, Eliott, 59 Aviner, Shlomo, 65, 115, 212 Academic Council for National, the. See Professors for a Strong Israel B’Sheva, 120 action B’Tselem, 36, 122 connective, 26 Barak, Ehud, 50–51, 95, 98, 147, 235 extreme, 16 Bar-Ilan University, 50, 187 radical, 16 Bar-Siman-Tov, Yaacov, 194, 216 tactical, 34 Bat Ayin Underground, the, 159 activism BDS. See Boycott, Divestment and moderate, 15–16 Sanctions transnational, 30–31 Begin, Manahem, 47, 48, 118–119, Adelson, Sheldon, 179, 190 157, 172 Airbnb, 136 Beit El, 105 Al Aqsa Mosque, the, 146 Beit HaArava, 45 Al-Aqsa Intifada. See the Second Intifada Beitar Illit, 67, 70, 99 Alfei Menashe, 100 Beitar Ironi Ariel, 170 Allon, Yigal, 45–46 Belafonte, Harry, 14 Alon Shvut, 88, 190 Ben Ari, Michael, 184 Aloni, Shulamit, 182 Bendaña, Alejandro, 24 Altshuler, Amos, 189 Ben-Gurion, David, 46 Amana, 76–77, 89, 113, 148, 153–154, 201 Ben-Gvir, Itamar, 184 American Friends of Ariel, 179–180 Benn, Menachem, 164 American Studies Association, 136 Bennett, Naftali, 76, 116, 140, 148, Amnesty International, 24 153, 190 Amona, 79, 83, 153, 157, 162, 250, Benvenisti, Meron, 1 251 Ben-Zimra, Gadi, 205 Amrousi, Emily, 67, 84 Ben-Zion, -

Radicalization of the Settlers' Youth: Hebron As a Hub for Jewish Extremism

© 2014, Global Media Journal -- Canadian Edition Volume 7, Issue 1, pp. 69-85 ISSN: 1918-5901 (English) -- ISSN: 1918-591X (Français) Radicalization of the Settlers’ Youth: Hebron as a Hub for Jewish Extremism Geneviève Boucher Boudreau University of Ottawa, Canada Abstract: The city of Hebron has been a hub for radicalization and terrorism throughout the modern history of Israel. This paper examines the past trends of radicalization and terrorism in Hebron and explains why it is still a present and rising ideology within the Jewish communities and organization such as the Hilltop Youth movement. The research first presents the transmission of social memory through memorials and symbolism of the Hebron hills area and then presents the impact of Meir Kahana’s movement. As observed, Hebron slowly grew and spread its population and philosophy to the then new settlement of Kiryat Arba. An exceptionally strong ideology of an extreme form of Judaism grew out of those two small towns. As analyzed—based on an exhaustive ethnographic fieldwork and bibliographic research—this form of fundamentalism and national-religious point of view gave birth to a new uprising of violence and radicalism amongst the settler youth organizations such as the Hilltop Youth movement. Keywords: Judaism; Radicalization; Settlers; Terrorism; West Bank Geneviève Boucher Boudreau 70 Résumé: Dès le début de l’histoire moderne de l’État d’Israël, les villes d’Hébron et Kiryat Arba sont devenues une plaque tournante pour la radicalisation et le terrorisme en Cisjordanie. Cette recherche examine cette tendance, explique pourquoi elle est toujours d’actualité ainsi qu’à la hausse au sein de ces communautés juives. -

Whiteness As an Act of Belonging: White Turks Phenomenon in the Post 9/11 World

WHITENESS AS AN ACT OF BELONGING: WHITE TURKS PHENOMENON IN THE POST 9/11 WORLD ILGIN YORUKOGLU Department of Social Sciences, Human Services and Criminal Justice The City University of New York [email protected] Abstract: Turks, along with other people of the Middle East, retain a claim to being “Cau- casian”. Technically white, Turks do not fit neatly into Western racial categories especially after 9/11, and with the increasing normalization of racist discourses in Western politics, their assumed religious and geographical identities categorise “secular” Turks along with their Muslim “others” and, crucially, suggest a “non-white” status. In this context, for Turks who explicitly refuse to be presented along with “Islamists”, “whiteness” becomes an act of belonging to “the West” (instead of the East, to “the civilised world” instead of the world of terrorism). The White Turks phenomenon does not only reveal the fluidity of racial categories, it also helps question the meaning of resistance and racial identification “from below”. In dealing with their insecurities with their place in the world, White Turks fall short of leading towards a radical democratic politics. Keywords: Whiteness, White Turks, Race, Turkish Culture, Post 9/11. INTRODUCTION: WHY STUDY WHITE TURKISHNESS Until recently, sociologists and social scientists have had very little to say about Whiteness as a distinct socio-cultural racial identity, typically problematizing only non-white status. The more recent studies of whiteness in the literature on race and ethnicity have moved us beyond a focus on racialised bodies to a broader understanding of the active role played by claims to whiteness in sustaining racism. -

Phenomenon, Vigilantism, and Rabbi Yitzchak Ginsburgh's

‘THE SIMPLE JEW’: THE ‘PRICE TAG’ PHENOMENON, VIGILANTISM, AND RABBI YITZCHAK GINSBURGH’S POLITICAL KABBALAH Tessa Satherley* ABSTRACT: This paper explores the Kabbalistic theosophy of Rabbi Yitzchak Ginsburgh, and allegations of links between his yeshiva and violent political activism and vigilantism. Ginsburgh is head of the yeshiva Od Yosef Chai (Joseph Still Lives) in Samaria/the northern West Bank. His students and colleagues have been accused by the authorities of violence and vandalism against Arabs in the context of ‘price tag’ actions and vigilante attacks, while publications by Ginsburgh and his yeshiva colleagues such as Barukh HaGever (Barukh the Man/Blessed is the Man) and Torat HaMelekh (The King’s Torah) have been accused of inciting racist violence. This paper sketches the yeshiva’s history in the public spotlight and describes the esoteric, Kabbalistic framework behind Ginsburgh’s politics, focusing on his political readings of Zoharic Kabbalah and teachings about the mystical value of spontaneous revenge attacks by ‘the simple Jew’, who acts upon his feelings of righteous indignation without prior reflection. The conclusion explores and attempts to delimit the explanatory power of such mystical teachings in light of the sociological characteristics of the Hilltop Youth most often implicated as price tag ‘operatives’ and existing scholarly models of vigilantism. It also points to aspects of the mystical teachings with potential for special potency in this context. Rabbi Yitzchak Ginsburgh (1944-) is a Chabad rabbi and head of the Od Yosef Chai (Joseph Still Lives) yeshiva in the Yitzhar settlement, near the major Palestinian population centre of Nablus (biblical Shechem). The yeshiva occupies an unusual discursive space – neither mainstream religious Zionist (though some of its teaching staff were educated in this tradition) nor formally affiliated with the Hasidic movement, despite Ginsburgh’s own affiliation with Chabad and despite his teachings being steeped in its Kabbalistic inheritance. -

Palestine About the Author

PALESTINE ABOUT THE AUTHOR Professor Nur Masalha is a Palestinian historian and a member of the Centre for Palestine Studies, SOAS, University of London. He is also editor of the Journal of Holy Land and Palestine Studies. His books include Expulsion of the Palestinians (1992); A Land Without a People (1997); The Politics of Denial (2003); The Bible and Zionism (Zed 2007) and The Pales- tine Nakba (Zed 2012). PALESTINE A FOUR THOUSAND YEAR HISTORY NUR MASALHA Palestine: A Four Thousand Year History was first published in 2018 by Zed Books Ltd, The Foundry, 17 Oval Way, London SE11 5RR, UK. www.zedbooks.net Copyright © Nur Masalha 2018. The right of Nur Masalha to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro by seagulls.net Index by Nur Masalha Cover design © De Agostini Picture Library/Getty All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Zed Books Ltd. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑272‑7 hb ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑274‑1 pdf ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑275‑8 epub ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑276‑5 mobi CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Introduction 1 1. The Philistines and Philistia as a distinct geo‑political entity: 55 Late Bronze Age to 500 BC 2. The conception of Palestine in Classical Antiquity and 71 during the Hellenistic Empires (500‒135 BC) 3. -

An Mora Constrts

Yitzchak Blau Rabbi Blau is a Ram at Yeshivat Hamivtar in Efrat, IsraeL. PLOUGHSHAS INTO SWORDS: CONTEMPORA RELIGIOUS ZIONISTS AN MORA CONSTRTS AUTHOR'S NOTE: When Jewish communities are threatened, we rightfully incline towards communal unity and are reluctant to engage in internal criti- cism. In the wake of recent events in Israel, some of which I have witnessed firsthand, one might question the appropriateness of publishing this article. Nevertheless, the article remains timely. It attempts to correct a perceived misrepresentation of yahadut, irrespective of political issues, and such a step is always relevant. Furthermore, the decision to delay our own moral ques- tioning during difficult times could lead in modern Israel to a de facto deci- sion never to raise such questions. Finally and most significantly, times of heightened anger, frustration and fear can cause cracks in the moral order to widen into chasms. I hope the reader will agree that the issues analyzed in the article remain very much worthy of discussion. The article does not advocate a particular political approach. While readers of a dovish inclination will no doubt find the article more congenial, it is the more right wing readers who truly stand to benefit from the discussion. It is precisely the militant excesses of the dati le)ummi world that enable and lead others to ignore their legitimate criticisms. The ability to combine a more right wing political view with a more moderate expression of Judaism would be both a kiddush hashem and more successful politically as well. "In ths situation of war for the land of our life and our eternal free- dom, the perfected form of our renewal appears: not just as the People of the Book-the galuti description given us by the genties- but rather as God's nation, the holy nation, possessors of the Divine Torah implanted therein, for whom the Book and the Sword descended intertwned from the heavens .