Phenomenon, Vigilantism, and Rabbi Yitzchak Ginsburgh's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Israel's National Religious and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict

Leap of Faith: Israel’s National Religious and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict Middle East Report N°147 | 21 November 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iv I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Religious Zionism: From Ascendance to Fragmentation ................................................ 5 A. 1973: A Turning Point ................................................................................................ 5 B. 1980s and 1990s: Polarisation ................................................................................... 7 C. The Gaza Disengagement and its Aftermath ............................................................. 11 III. Settling the Land .............................................................................................................. 14 A. Bargaining with the State: The Kookists ................................................................... 15 B. Defying the State: The Hilltop Youth ........................................................................ 17 IV. From the Hills to the State .............................................................................................. -

CV July 2017

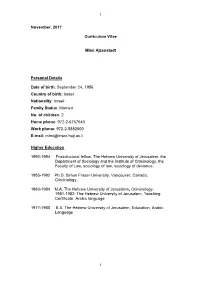

1 November, 2017 Curriculum Vitae Mimi Ajzenstadt Personal Details Date of birth: September 24, 1956 Country of birth: Israel Nationality: Israeli Family Status: Married No. of children: 2 Home phone: 972-2-6767540 Work phone: 972-2-5882600 E-mail: [email protected] Higher Education 1992-1994 Post-doctoral fellow, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the Department of Sociology and the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law, sociology of law, sociology of deviance. 1985-1992 Ph.D. Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, Canada, Criminology. 1980-1984 M.A. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Criminology. 1981-1982: The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Teaching Certificate, Arabic language 1977-1980 B.A. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Education, Arabic Language 1 2 Appointments at the Hebrew University 2012- present Full Professor, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work and Social Welfare. 2007– 2012 Associate Professor, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work and Social Welfare. 2002- 2007 Senior Lecturer, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work and Social Welfare. 1994-2002 Lecturer, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work. Service in other Academic Institutions Summer, 2011 Visiting Professor, Cambridge University. Summer, 2010 Visiting Professor. University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada. 2005 -2006 Visiting Professor. University of Maryland, Maryland, USA. Winter, 2000 Visiting Scholar. Stockholm University, Sweden. Fall 1999 Visiting Scholar. Yale University, New-Haven, Connecticut, U.S.A., Law School. -

Yitzhar – a Case Study Settler Violence As a Vehicle for Taking Over Palestinian Land with State and Military Backing

Yitzhar – A Case Study Settler violence as a vehicle for taking over Palestinian land with state and military backing August 2018 Yitzhar – A Case Study Settler violence as a vehicle for taking over Palestinian land with state and military backing Position paper, August 2018 Research and writing: Yonatan Kanonich Editing: Ziv Stahl Additional Editing: Lior Amihai, Miryam Wijler Legal advice: Atty. Michael Sfard, Atty. Ishai Shneidor Graphic design: Yuda Dery Studio English translation: Maya Johnston English editing: Shani Ganiel Yesh Din Public council: Adv. Abeer Baker, Hanna Barag, Dan Bavly, Prof. Naomi Chazan, Ruth Cheshin, Akiva Eldar, Prof. Rachel Elior, Dani Karavan, Adv. Yehudit Karp, Paul Kedar, Dr. Roy Peled, Prof. Uzy Smilansky, Joshua Sobol, Prof. Zeev Sternhell, Yair Rotlevy. Yesh Din Volunteers: Rachel Afek, Dahlia Amit, Maya Bailey, Hanna Barag, Michal Barak, Atty. Dr. Assnat Bartor, Osnat Ben-Shachar, Rochale Chayut, Beli Deutch, Dr. Yehudit Elkana, Rony Gilboa, Hana Gottlieb, Tami Gross, Chen Haklai, Dina Hecht, Niva Inbar, Daniel A. Kahn, Edna Kaldor, Nurit Karlin, Ruth Kedar, Lilach Klein Dolev, Dr. Joel Klemes, Bentzi Laor, Yoram Lehmann RIP, Judy Lots, Aryeh Magal, Sarah Marliss, Shmuel Nachmully RIP, Amir Pansky, Talia Pecker Berio, Nava Polak, Dr. Nura Resh, Yael Rokni, Maya Rothschild, Eddie Saar, Idit Schlesinger, Ilana Meki Shapira, Dr. Tzvia Shapira, Dr. Hadas Shintel, Ayala Sussmann, Sara Toledano. Yesh Din Staff: Firas Alami, Lior Amihai, Yudit Avidor, Maysoon Badawi, Hagai Benziman, Atty. Sophia Brodsky, Mourad Jadallah, Moneer Kadus, Yonatan Kanonich, Atty. Michal Pasovsky, Atty. Michael Sfard, Atty. Muhammed Shuqier, Ziv Stahl, Alex Vinokorov, Sharona Weiss, Miryam Wijler, Atty. Shlomy Zachary, Atty. -

1. Keter (Primary Meaning: Crown

1. KETER (PRIMARY MEANING: CROWN. ALSO KNOWN AS: UPPER CROWN, AYIN (NOTHINGNESS), CHOKHMAH PENIMIT (INTERNAL WISDOM), MAHSHAVAH ELOHIT (DIVINE THOUGHT), SPIRIT OF G-D, ROOT OF ROOTS, MYSTERIOUS WISDOM, EHYEH ASHER EHYEH, (I AM THAT I AM) 2. CHOKHMAH (PRIMARY MEANING: WISDOM. ALSO KNOWN AS: REVELATION, THE PRIMORDIAL TORAH (THE TORAH THAT EXISTED BEFORE CREATION), FATHER, YESH ME-AYIN (BEING FROM NOTHINGNESS), BEGINNING, YAH, YHVH) 3. BINAH (PRIMARY MEANING: UNDERSTANDING. ALSO KNOWN AS: INTELLECT, TESHUVAH (REPENTANCE), REASON, PALACE, TEMPLE, WOMB, UPPER MOTHER, JERUSALEM ABOVE, FREEDOM, JUBILEE, "YHVH PRONOUNCED AS ELOHIM") 4. CHESED (PRIMARY MEANING: MERCY. ALSO KNOWN AS: GRACE, LOVE OF G-D, RIGHT ARM OF G-D, WHITE, EL, ASSOCIATED WITH ABRAHAM) 5. GEVURAH (ALSO CALLED "DIN" - PRIMARY MEANING: JUDGMENT. ALSO KNOWN AS: STRENGTH, SEVERITY, FEAR OF G-D, LEFT ARM OF G-D, RED, ELOHIM, YAH, ASSOCIATED WITH ISAAC) 6. TIPHERET (PRIMARY MEANING: BEAUTY. ALSO KNOWN AS: HARMONY, RACHAMIM (COMPASSION), THE ATTRIBUTE OF MERCY, THE WRITTEN TORAH, BRIDEGROOM, HUSBAND, SON, KING, FATHER, MESSIAH, TABERNACLE/TEMPLE, THE HOLY TREE, (TREE OF LIFE), HEAVEN, THE LETTER "VAV," CREATOR, GATE OF RIGHTEOUSNESS, SUN, "THE HOLY ONE BLESSED BE HE," HA-SHEM, YHVH, YHVH-ELOHIM, THE GREAT NAME, THE UNIQUE NAME, THE LUCID MIRROR, OPEN MIRACLES, LULAV [ON SUCCOTH], THE SHOFAR [AS RELATED TO THE MITZVOT OF BLOWING THE SHOFAR], GREEN, TEFILLIN OF THE HEAD, ASSOCIATED WITH JACOB) 7. NETZACH (PRIMARY MEANING: VICTORY. ALSO KNOWN AS: ETERNITY, PROPHECY, ORCHESTRATION, INITIATIVE, PERSISTENCE, BITACHON (CONFIDENCE), RIGHT LEG, "HOSTS OF YHVH," ASSOCIATED WITH MOSES) 8. HOD (PRIMARY MEANING: GLORY. ALSO KNOWN AS: MAJESTY, SPLENDOR, REVERBERATION, PROPHECY, SURRENDER, TEMIMUT (SINCERITY), ANCHOR, STEADFASTNESS, LEFT LEG, "HOSTS OF ELOHIM," ASSOCIATED WITH AARON) 9. -

Privatizing Religion: the Transformation of Israel's

Privatizing religion: The transformation of Israel’s Religious- Zionist community BY Yair ETTINGER The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. This paper is part of a series on Imagining Israel’s Future, made possible by support from the Morningstar Philanthropic Fund. The views expressed in this report are those of its author and do not represent the views of the Morningstar Philanthropic Fund, their officers, or employees. Copyright © 2017 Brookings Institution 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20036 U.S.A. www.brookings.edu Table of Contents 1 The Author 2 Acknowlegements 3 Introduction 4 The Religious Zionist tribe 5 Bennett, the Jewish Home, and religious privatization 7 New disputes 10 Implications 12 Conclusion: The Bennett era 14 The Center for Middle East Policy 1 | Privatizing religion: The transformation of Israel’s Religious-Zionist community The Author air Ettinger has served as a journalist with Haaretz since 1997. His work primarily fo- cuses on the internal dynamics and process- Yes within Haredi communities. Previously, he cov- ered issues relating to Palestinian citizens of Israel and was a foreign affairs correspondent in Paris. Et- tinger studied Middle Eastern affairs at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and is currently writing a book on Jewish Modern Orthodoxy. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-13864-3 — the Israeli Settler Movement Sivan Hirsch-Hoefler , Cas Mudde Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-13864-3 — The Israeli Settler Movement Sivan Hirsch-Hoefler , Cas Mudde Index More Information Index 1948 Arab–Israeli War, the, 2 Ariel, Uri, 76, 116 1949 Armistice Agreements, the, 2 Arutz Sheva, 120–121, 154, 205 1956 Sinai campaign, the, 60 Ashkenazi, 42, 64, 200 1979 peace agreement, the, 57 Association for Retired People, 23 Australia, 138 Abrams, Eliott, 59 Aviner, Shlomo, 65, 115, 212 Academic Council for National, the. See Professors for a Strong Israel B’Sheva, 120 action B’Tselem, 36, 122 connective, 26 Barak, Ehud, 50–51, 95, 98, 147, 235 extreme, 16 Bar-Ilan University, 50, 187 radical, 16 Bar-Siman-Tov, Yaacov, 194, 216 tactical, 34 Bat Ayin Underground, the, 159 activism BDS. See Boycott, Divestment and moderate, 15–16 Sanctions transnational, 30–31 Begin, Manahem, 47, 48, 118–119, Adelson, Sheldon, 179, 190 157, 172 Airbnb, 136 Beit El, 105 Al Aqsa Mosque, the, 146 Beit HaArava, 45 Al-Aqsa Intifada. See the Second Intifada Beitar Illit, 67, 70, 99 Alfei Menashe, 100 Beitar Ironi Ariel, 170 Allon, Yigal, 45–46 Belafonte, Harry, 14 Alon Shvut, 88, 190 Ben Ari, Michael, 184 Aloni, Shulamit, 182 Bendaña, Alejandro, 24 Altshuler, Amos, 189 Ben-Gurion, David, 46 Amana, 76–77, 89, 113, 148, 153–154, 201 Ben-Gvir, Itamar, 184 American Friends of Ariel, 179–180 Benn, Menachem, 164 American Studies Association, 136 Bennett, Naftali, 76, 116, 140, 148, Amnesty International, 24 153, 190 Amona, 79, 83, 153, 157, 162, 250, Benvenisti, Meron, 1 251 Ben-Zimra, Gadi, 205 Amrousi, Emily, 67, 84 Ben-Zion, -

The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿavoda Zara By

The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿAvoda Zara By Mira Beth Wasserman A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley in Jewish Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Daniel Boyarin, chair Professor Chana Kronfeld Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Kenneth Bamberger Spring 2014 Abstract The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿAvoda Zara by Mira Beth Wasserman Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel Boyarin, chair In this dissertation, I argue that there is an ethical dimension to the Babylonian Talmud, and that literary analysis is the approach best suited to uncover it. Paying special attention to the discursive forms of the Talmud, I show how juxtapositions of narrative and legal dialectics cooperate in generating the Talmud's distinctive ethics, which I characterize as an attentiveness to the “exceptional particulars” of life. To demonstrate the features and rewards of a literary approach, I offer a sustained reading of a single tractate from the Babylonian Talmud, ʿAvoda Zara (AZ). AZ and other talmudic discussions about non-Jews offer a rich resource for considerations of ethics because they are centrally concerned with constituting social relationships and with examining aspects of human experience that exceed the domain of Jewish law. AZ investigates what distinguishes Jews from non-Jews, what Jews and non- Jews share in common, and what it means to be a human being. I read AZ as a cohesive literary work unified by the overarching project of examining the place of humanity in the cosmos. -

Ultraorthodox Jews in Israel – Epidemic As a Measure of Challenges Marek Matusiak

OSW Commentary CENTRE FOR EASTERN STUDIES NUMBER 341 23.06.2020 www.osw.waw.pl Ultraorthodox Jews in Israel – epidemic as a measure of challenges Marek Matusiak In Israel as in other countries, when the COVID-19 epidemic surfaced it exacerbated the existing divi- sions and tensions in society. A group that came under severe attack from the public was the Jewish Ultraorthodox population (the Haredi). This was due to disregard on the part of certain ultraorthodox groups of the restrictions imposed in response to the epidemic and an exceptionally high infection rate in that community – as much as 70% of cases recorded from February until May this year affected members of that community.1 This non-conformity with the regulations by some Haredi (in fact a distinct minority) resonated broadly because it was an element of a decades-long heated dispute over the state’s approach towards the group and its place in Israeli society. Over the years, the issue has repeatedly caused severe shockwaves (including collapse of government coalitions). The stance adopted by the Haredi during the initial phase of the epidemic provided critics of the Haredi with new arguments that they are de facto a law unto themselves, and as a result are becoming increasingly socially and politically problematic. While COVID-19 cannot be expected to significantly change the subjects under debate, the arguments used in the debate, or the balance of power, it will make the dispute even more complex than before the epidemic and lead to greater polarisation. This will further complicate Israel’s efforts to meet challenges posed by the rapid increase in the community’s population. -

DAY-BY-DAY HALACHIC GUIDE Detailed Instructions on the Laws and Customs for the Month of Tishrei 5778

DAY-BY-DAY HALACHIC GUIDE Detailed instructions on the laws and customs for the month of Tishrei 5778 PART ONE: MONDAY 20 ELUL 5777 UNTILL WEDNSDAY 14 TISHREI 5778 FROM THE BADATZ OF CROWN HEIGHTS 373 Kingston Ave. • 718-221-9939 Shop Oneline www.boytique.com Wishing all toshvei haschechuna a כתיבה וחתימה טובה לשנה טובה ומתוקה DC Life & Health [email protected] Just Walk In or Book Online Most medicaid plans accepted here 555 LEFFERTS AVENUE P 718 360 8074 BROOKLYN, NY 11225 F 718 407 2469 WWW.KAMINHEALTH.COM לעילוי נשמת מרת אסתר פריאל בת ר׳ משה ע“ה כהן נפטרה ט׳ תשרי ה׳תשע“ה ת.נ.צ.ב.ה. נתרם ע“י מאיר הכהן וזוגתו שרה שיחיו כהן If you would like sponsor future publications or support our Rabbonim financially call: (347) 465-7703 or on thewww.crownheightsconnect.com website created by Friends of Badatz Advertising in the Day-by-Day Halachic Guide does not necessarily constitute a Badatz endorsement of products or services BY THE BADATZ OF CROWN HEIGHTS 3 B”H DAY-BY-DAY HALACHIC GUIDE Detailed instructions on the laws and customs for the month of Tishrei 5778 Part One: Monday 20 Elul 5777 untill Wednsday 14 Tishrei 5778 Distilled from a series of public shiurim delivered by Horav Yosef Yeshaya Braun, shlita member of the Badatz of Crown Heights Addendum on Page 59 Calendar Currents 4 DAY-BY-DAY HALACHIC GUIDE TISHREI 5778 ONE MINUTE HALACHA AUDIO | TEXT Delivered by Horav Yosef Yeshaya Braun, shlita , Mara D’asra and member of the Badatz of Crown Heights GET IT DAILY CALL: (347) 696-7802. -

Radicalization of the Settlers' Youth: Hebron As a Hub for Jewish Extremism

© 2014, Global Media Journal -- Canadian Edition Volume 7, Issue 1, pp. 69-85 ISSN: 1918-5901 (English) -- ISSN: 1918-591X (Français) Radicalization of the Settlers’ Youth: Hebron as a Hub for Jewish Extremism Geneviève Boucher Boudreau University of Ottawa, Canada Abstract: The city of Hebron has been a hub for radicalization and terrorism throughout the modern history of Israel. This paper examines the past trends of radicalization and terrorism in Hebron and explains why it is still a present and rising ideology within the Jewish communities and organization such as the Hilltop Youth movement. The research first presents the transmission of social memory through memorials and symbolism of the Hebron hills area and then presents the impact of Meir Kahana’s movement. As observed, Hebron slowly grew and spread its population and philosophy to the then new settlement of Kiryat Arba. An exceptionally strong ideology of an extreme form of Judaism grew out of those two small towns. As analyzed—based on an exhaustive ethnographic fieldwork and bibliographic research—this form of fundamentalism and national-religious point of view gave birth to a new uprising of violence and radicalism amongst the settler youth organizations such as the Hilltop Youth movement. Keywords: Judaism; Radicalization; Settlers; Terrorism; West Bank Geneviève Boucher Boudreau 70 Résumé: Dès le début de l’histoire moderne de l’État d’Israël, les villes d’Hébron et Kiryat Arba sont devenues une plaque tournante pour la radicalisation et le terrorisme en Cisjordanie. Cette recherche examine cette tendance, explique pourquoi elle est toujours d’actualité ainsi qu’à la hausse au sein de ces communautés juives. -

Attitudes Toward Jewish-Gentile Relations in the Jewish Tradition and Contemporary Israel* Charles S Liebman

Attitudes toward Jewish-Gentile Relations in the Jewish Tradition and Contemporary Israel* Charles S Liebman My research concerns over the past few years touch upon the inter relationship between beliefs, values and norms on the one hand and tradition on the other. Beliefs, values and norms, as I use the terms, are concerned with how we think the world functions, which in turn is closely related to our aspirations, to what we want or don't want, what we think is right or wrong, standards of conduct we deem appropriate and inappropriate and rules of behaviour. The tradition is our perception of the beliefs, values and norms of the past; what we think were the beliefs, values and norms of the culture with which we identify. My special interest lies in trying to establish with as much precision as I can, the interrelationship between contemporary values and the tradition. What I am going to share with you this evening are some of my problems and some of my reflections, rather than answers f Political Studies at Bar-Han which alas, I do not have. The only way to approach the problem as a faculty member of both the intelligently is to compare a specific aspect of the tradition with a _va University. He has also served specific set of contemporary values. • Theological Seminary, Brown My lecture is about Jewish-Gentile relations, with special reference to : Town. His most recent books are relations between Israel and 'the nations of the world'; what these Judaism and Political Culture in relations are and what they should be, as reflected in the beliefs, values oming Piety and Polity: Religion and norms of contemporary Israelis and in the Jewish tradition. -

Yeshivah College 2019 School Performance Report

בס”ד YESHIVAH COLLEGE 2019 SCHOOL PERFORMANCE REPORT Yeshivah College Educating for Life Yeshivah College Educating for Life PERFORMANCE INFORMATION REPORT 2019 This document is designed to report to the public key aspects identified by the State and Commonwealth Governments as linked to the performance of Schools in Australia. Yeshivah College remains committed to the continual review and improvement of all its practices, policies and processes. We are suitably proud of the achievements of our students, and the efforts of our staff to strive for excellence in teaching and outcomes. ‘Please note: Any data referencing Yeshivah – Beth Rivkah Colleges (or YBR) is data combined with our partner school, Beth Rivkah Ladies College. All other data relates specifically toY eshivah. Vision Broadening their minds and life experiences, Yeshivah - Beth Rivkah students are well prepared for a life of accomplishment, contribution and personal fulfilment. Our Values Jewish values and community responsibility are amongst the core values that distinguish Yeshivah - Beth Rivkah students. At Yeshivah - Beth Rivkah Colleges we nurture and promote: Engaging young minds, adventurous learning, strong Jewish identity, academic excellence and community responsibility. Our Mission We are committed to supporting the individual achievement and personal growth of each of our students. Delivering excellence in Jewish and General studies, a rich and nurturing environment and a welcoming community, our students develop a deep appreciation of Yiddishkeit (their Jewish identity) andT orah study. 1. PROFESSIONAL ENGAGEMENT STAFF ATTENDANCE In 2019, Yeshivah – Beth Rivkah Colleges (YBR) have been privileged to have a staff committed to the development of all aspects of school life. Teaching methods were thorough, innovative and motivating, and there was involvement in improving behavioural outcomes, curricula, professional standards and maintaining the duty of care of which the school is proud.